Recent issues of Antiquarian Horology

Volume 46, Issue 3, September 2025

On the front cover: A view from the clock tower in Rouen. Photo Thomas Muff. The Gros Horologe in Rouen was on the itinerary of the AHS Study Tour to Northern France and Belgium, undertaken in May this year and reported in the section AHS News in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

Art and symbols on monastic clocks of Mount Athos

by Spiridion Azzopardi (pp. 318-340)

Summary: This article explores the meaning of art and symbols on clocks of the Greek monastic state of Mount Athos. The main focus is on one particular symbol, the hexafoil. The discussion includes brass lantern clocks, longcase clocks and turret clocks, as well as the monastic buildings themselves.

Belgian carillons in UK clock towers. Part 1

by Darlah Thomas (pp. 341-355)

Summary: This article began as a talk delivered at the Turret Clock Forum at the School of Jewellery, Birmingham City University on 23 October 2024. The day’s theme was ‘the face and voice of the clock’, i.e. dials and bells. Since that day, more information has come to light which has extended the content. The article centres on the carillons of bells which were imported from Belgium and the newly developed carillon machine manufactured by Gillett and Bland from 1867–8 in projects in the UK: three for churches and one for a private setting. These were ‘of their time’ and suffered from criticism and circumstances to such an extent that only one project has remained intact. In common with many new technologies, subsequent innovations have enabled their legacy — the use of this genre as symbols of peace has seen the installation of many peace towers and war memorials housing carillons throughout the world.

Time in Biscuit Town

by James Nye (pp. 356-362)

Summary: Photographing the evocative stone relief of three camels above the entrance to Peek House, for use on a Christmas card, led to researching the commitment of the London biscuit manufactury of Peek Frean to precision and modernity, reflected in both mechanical and electric clock systems. Its Drummond Road clock tower served not only as a practical marker of time but also as a symbol of identity for the factory and its surrounding community.

A remarkable correspondence

by Andrew King (pp. 363-369)

Summary: This article offers an introduction to the correspondence between Colonel Humphrey Quill (1897–1987), the biographer of John Harrison (John Harrison the Man who found Longitude, John Baker 1966) and John Martin (1895–1978), local historian of Barrow upon Humber. The series of ninety-eight letters extending to more than 500 autograph pages, both sides of a correspondence over a period of twenty years, 1957–1977, reveals, for the first time, the extensive research into John Harrison and his family life in Barrow upon Humber in the early years of the eighteenth century before Harrison moved to London to further his life’s work in the development of marine timekeepers.

Museum profile: The Frick Collection

by Bob Frishman (pp. 370-376) (Read this article here)

‘Unfreezing Time #23’ by Patricia Fara (pp. 377-379) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, Book reviews, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 46, Issue 2, June 2025

On the front cover: Detail of the Clock of the Creation of the World. Photo © Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Thierry Ollivier. The clock is illustrated full-page on page 249.

This issue contains the following articles:

The Vindication of Mr. Symon Douw. The alleged infringement of Salomon Coster’s pendulum patent

by Wim Borgdorff, (pages 165-182)

Summary: The author’s investigation into his Claude Pascal Hague clock (Plomp - D151) led to an exploration of its historical context and the patent dispute between Coster and Huygens against Symon Douw. In the The Hague City Archives, the original manuscript ‘Akte der Demonstratie’ of the ‘Hof van Holland, Zeeland en West-Friesland’ (The Court), dated 9 and 10 October 1658, was discovered. A transcript of this document is published here in an English translation, and the dispute is described and evaluated.

The Harlows of Ashbourne — from small-town clockmakers to major movement manufacturers

by John A. Robey, (pages 183-199)

Summary: This article describes the rise of Samuel Harlow from a typical small-town clockmaker, watchmaker and jeweller in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, from about 1772. He became one of the most important manufacturers of longcase clock movements and clock castings in Britain, with a warehouse in Birmingham. His son Robert continued the business, followed by his widow Amelia, then her sons Benjamin and, for a short time, William, until it was sold to the Davenport family who continued into the twentieth century.

From man to machine: the history of the winding of the Great Clock of Westminster,

by Keith Scobie-Youngs, (pages 200-215)

Summary: This article is closely adapted from the script delivered as the Dingwall Beloe Lecture on 2 November 2023 at the British Museum. As part of the Elizabeth Tower project completed between 2017 and 2023, Keith Scobie-Youngs and his team from the Cumbria Clock Company worked with colleagues from the Westminster Palace clock team to restore and conserve the Great Clock, commonly known as Big Ben. An important element in this project was the decision to restore to working order an extraordinarily complicated and sophisticated automatic winding system, first installed just before the Great War, and which had fallen into disrepair. In his lecture, Keith charted both the challenges and the triumphs associated with this element of the larger project. (Read this article here)

Identification of the effect of humidity on chronometer rate: A belated response to George Daniels

by Matěj Bělín, (pages 216-226)

Summary: Speaking on 23 June 1990 at the American Watchmakers’ Institute’s 30th Anniversary, George Daniels said: ‘I am sure that many of the small variations in rate found in some of the Hamilton chronometers were due to change in humidity, which nobody ever bothered to record.’ This paper provides empirical support to the quoted claim but also finds an important role for air pressure.

John Jefferys and the Jefferies clock

by Jonathan Betts, (pages 227-236)

Summary: For horologists, the name of John Jefferys (c.1703–1754) will invariably be associated with the great pioneer of the chronometer, John Harrison (1693–1776). It was Jefferys who was commissioned by Harrison to make the now celebrated experimental pocket watch, dated 1753, which, with its unexpectedly excellent performance, inspired Harrison to change course in his timekeeper design and concentrate on developing a smaller timekeeper for the longitude. The making of the watch was however not the first professional connection between the two makers, and this article looks at a unique regulator which was the result of an earlier association.

A lifelong companion

by James Nye (pages 237-242)

Summary: Clocks rarely turn up with fully researched histories attached, but SJ Bean Clocks recently sold a longcase clock with a marvellous documentary provenance, and I am very grateful for being allowed to use it. A bundle of documents kept in the case reveal a deep and lifelong relationship between the clock and a former owner. I am also grateful to Dr Adrian Hodge for providing information about the family, and some relevant and highly evocative photographs.

Versailles: Science and Splendour, (pages 243-249)

Note: Moll Flanders and the art of stealing watches

by Peter de Clercq, (pages 252-254)

‘Unfreezing Time #22’ by Patricia Fara (pages 250-251) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, Book reviews, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 46, Issue 1, March 2025

On the front cover: Detail of a cabinet musical clock signed James Cox, London, dated 1766, formerly in the collection of King Farouk of Egypt. © Bonhams, London. The clock is illustrated full-page in Part 2 of Roger Smith’s article ‘James Cox: manufacturer and merchant’ published in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

James Cox: manufacturer and merchant – Part 2

by Roger Smith (pages 21-47)

Summary: Part 1 covered the background to Cox’s involvement in the export of clocks and watches to the ‘East Indies’. It also looked at the production of larger articles like clocks and automata in Cox’s own workshop and by his known collaborators. Part 2 considers the production of jewellery and other small articles by Cox, before discussing the more restricted mercantile role that he adopted towards the end of his career.

Lantern clock conversions – a technical survey

by John A Robey (pages 48-68)

Summary: Before 1658 all lantern clocks were made with a balance-controlled verge escapement, there being no practical alternative. However, their timekeeping was very poor, with both large day-to-day variations and long-term drifting. When the short pendulum and later, in the late 1660s, the long pendulum were introduced, few balance lantern clocks escaped being updated to pendulum control. At the same time most had their duration increased and often the two weights were changed to a single weight on a Huygens endless rope or chain. This article discusses these different conversions and the various alternative constructions employed. It looks at examples of clocks that illustrate some of the variety of combinations that are found.

Who invented the duplex escapement?

by Luigi Petrucci (pages 69-85)

Summary: The question of who invented the duplex escapement has been a matter of speculation for well over two centuries. This article tries to put the available information into order and into context, separating facts from hearsay, and highlighting potential misunderstandings. It also discusses two possible technical developments in which the duplex escapement came to be. (Read this article here)

Peter Medcalf (c. 1530–1592), turret clock maker

by Adrian A Finch, Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages 86-99)

Summary: Peter Medcalf was a turret clock maker in Elizabethan London, free of the Clothworkers’ Company by Patrimony in 1565, and very likely the first free clockmaker within a London guild. Medcalf built and maintained turret clocks from a workshop in St Olave’s Southwark, supplying an expanding market in late Tudor England. He employed smiths from the metalworking regions of Eastern Flanders, one of the most advanced metalworking regions in Europe. Immigrant makers in his business trained English apprentices, thereby bringing expertise from the Low Countries to London. His workshop was dominant in late Tudor London and he may be the maker of unattributed turret clocks from the period. He is also the historical nexus point as we trace back the origins of many of the turret clockmaking community in Early Modern London.

‘Unfreezing Time #21’ by Patricia Fara (pages 100-102) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 45, Issue 4 December 2024

On the front cover: Detail of a silver kettle made by Edward John and Willliam Barnard, presented by the Clockmaker’s Company to Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy. It is one of the objects in the exhibition Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy: A Champion of British Craftsmanship, which is in the Clockmakers’ Museum in London until 2 November 2025. Photo: Science Museum Group / The Clockmakers’ Museum. © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum.

This issue contains the following articles:

James Cox: manufacturer and merchant – Part 1

by Roger Smith (pages 463-481)

Summary: This article has been developed from a lecture given at the University of Neuchâtel on 28 May 2013. It is in two parts, with Part 1 covering the background to Cox’s involvement in the export of clocks and watches to the ‘East Indies’ – the term commonly applied by eighteenth-century Europeans to an enormous region of South- and East Asia which included India, Indonesia and China. It also looks at the production of larger articles like clocks and automata in Cox’s own workshop and by his known collaborators. Part 2 will consider the production of jewellery and other small articles by Cox, before discussing the more restricted mercantile role that he adopted towards the end of his career.

John Harrison (1693–1776): a legacy of invention and engineering. Part 2

by Ann McBroom (pages 482-504)

Summary: John ‘Longitude’ Harrison has been the subject of multiple excellent publications detailing his life and horological achievements, some only recently confirmed. The current paper is designed as a supplement. Part I explored the genealogy of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren and offers a broad summary of their lives. Part 2 looks in greater depth at the inventive and engineering skills many displayed, and explores what happened to JLH’s writings and instruments as they passed through these first few generations.

Reassessment of the painted clock dials of Thomas Pyke Sr & Jr of Bridgwater and an introduction to the painted clock dials of Cox of Taunton, Somerset. Part 2

by Nial Woodford (pages 505–518)

Summary: The first part of this article reassessed the painted clock dials of the Thomas Pyke foundry of Bridgwater, Somerset. This second part discusses the little-known Cox foundry at Taunton, a town situated some eleven miles southwest of Bridgwater. In the period 1821–1840 it bought in blanks for finishing, and manufactured painted iron dials, nineteen examples of which are presented here.

No. 67 Fleet Street, after Thomas Tompion – and some nineteenth-century plans

by James Nye (pages 519-529)

Summary: In the absence of other information, one might expect Thomas Tompion’s final premises to be fronted by his own shop at street level. Yet we have long known he shared his building. Evans, Carter & Wright discussed furniture-maker Braem, saddler Tesmond, and haberdasher Clutterbuck as some examples of co-tenants, but no detailed consideration has previously been given to what the passer-by might have seen at the street-level frontage of 67 Fleet Street. Further, little attention has been focussed on how much space was available for new-making and servicing of clocks and watches when Tompion and Graham were residents. This article discusses some hitherto unremarked plans of the premises from the mid-nineteenth century, which probably offer our best clues as to the square footage and footprint of the property. In the main it explores the use of the building – certainly the shop-front – over the 120 years or so after Graham left, until it was finally demolished, and highlights the different uses to which the internal space may have been put, for retail and for bench work.

Mozart’s watches

by Peter de Clercq (pages 530-540)

Summary: From the abundant surviving correspondence of the Mozart family, we learn that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) owned five gold watches. The letters shed an interesting light on the way he acquired them, and on his own thoughts about them. We know very little of what became of them after his death; only two watches said to have belonged to him are known, and for both the provenance can be doubted. In one letter Mozart refers to the current fashion for men to wear two watches, and this is picked up as a side-theme in this article. (Read this article here)

Clocks at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

by Bob Frishman (pages 541-545)

‘Unfreezing Time #20’ by Patricia Fara (pages 546-547) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

Volume 45, Issue 3 September 2024

On the front cover: Close-up of a sculpture representing Hercules carrying a celestial globe with a clock signed on the dial by Abraham-Louis Breguet. It is on display in the Royal Palace in Madrid. (Photo Keith Scobie-Youngs). It was seen during the Society’s Study Tour to Spain, which is reported in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

John Harrison (1693–1776): a legacy of invention and engineering. Part 1

by Ann McBroom (pages 318–348)

Summary: John ‘Longitude’ Harrison has been the subject of multiple excellent publications detailing his life and horological achievements, some only recently confirmed. The current paper is designed as a supplement: Part I explores the genealogy of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren and offers a broad summary of their lives. Part 2 looks in greater depth at the inventive and engineering skills many displayed, and explores what happened to JLH’s writings and instruments as they passed through these first few generations.

Italian grande-sonnerie whizzing work striking

by John A Robey (pages 349–362)

Summary: This article discusses the specifically Italian system of whizzing-work that produces grande-sonnerie using only one striking train. After describing the principles of whizzing-work, four clocks are considered that all employ this idiosyncratic system. While the basic method is the same for the first three clocks, which have two-hands, they show regional variations and different arrangements to produce similar results. The fourth clock is likely to be the earliest one described here, and differs considerably in the layout of its striking-work. All four clocks have different escapements and dials, two of the dials being very unusual, possibly unique.

Reassessment of the painted clock dials of Thomas Pyke Sr & Jr of Bridgwater and an introduction to the painted clock dials of Cox of Taunton, Somerset. Part 1

by Nial Woodford (pages 363–379)

Summary: This is the first part of a two-part treatise reassessing the painted clock dials of the Thomas Pyke foundry of Bridgwater, Somerset and the introduction of a believable link with a number of painted dials emanating from the little-known Cox foundry of Taunton. The review of Pyke dials is based on communications to the author post publication of an article concerning Thomas Pyke’s pewter enhanced painted dials published in the June and September 2015 editions of the journal.

AHS Study Tour to Spain

(pages 412-428)

Summary: A richly illustrated report of the recent tour to Spain. (Read this article here)

Note: on the AHS Grant of Arms (pages 395–397)

‘Unfreezing Time #19’ by Patricia Fara (pages 380-381) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

Volume 45, Issue 2 June 2024

On the front cover: Seiko Museum fusion of customer watches burned and melted during the 1923 great earthquake. Dug from the ruins of the Seikosha shop. Photo Bob Frishman.

For details see his article Horology in Tokyo in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City – an exhibition review

by Ian White (pages 166-175)

Summary: Zimingzhong: Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City was the title of an exhibition held at the Science Museum in London from 1 February to 2 June 2024. It was initially planned for 2020, but was postponed because of the pandemic. It brought to London an unprecedented exposure of the great skills of London clockmaking aimed at a totally different market from that of Europe. The exhibits came from the Palace Museum in Beijing, which has the largest collection of clocks in the world, a collection made by the Emperor Ch’ien-lung, who reigned from 1736 to 1796

Dismantling the ‘East School’ – Edward East and the clock trade in seventeenth-century London

by Richard Newton (pages 176-196)

Summary: The article summarises a London Lecture given by the author on 13 July 2023 and suggests that Edward East was acting principally as a retailer of clocks manufactured by others. By examining the movements of clocks signed by East we can see that they correspond with the work of John Hilderson, Ahasuerus Fromanteel, William Clement, Samuel Knibb and others. Further groups of movements from a common source but different signatures can also be identified and suggestions as to the maker are made. (Read this article here)

John Hilderson (?–1665): An update

by James Nye (pages 197-205)

Summary: To date, our knowledge of John Hilderson has best been brought together in the substantial piece of work by Anthony Weston in the June 2000 edition of Antiquarian Horology. Richard Newton’s recent work revealing Edward East’s sources for movements confirmed John Hilderson as the source for East’s pendulum clock movements in the first half of the 1660s (see Richard’s article in this journal). The recent discovery of the 1666 inventory of Hilderson’s house and workshop prompts a re-evaluation of our knowledge of the details of this important early maker.

Watertight pocket watches known as explorers’ watches, retailed by Herbert Blockley & Co., 41 Duke Street, St James, London

by Simon Davidson (pages 206-216)

Summary: This paper examines the retailing by Herbert Blockley & Co. of watertight pocket watches manufactured by Usher & Cole, known as explorers’ watches, to meet the need for accurate timekeeping in humid conditions. It met a need amongst the public travelling or working particularly in polar or tropical or latitudes, and is also illustrated by the Royal Geographical Society adopting this case model for supply to their sponsored expeditions. The paper highlights the output and the two models of watertight watches that Herbert Blockley retailed over the period 1890 to 1917.

Travel journals and the history of horology

by Peter de Clercq (pages 217-235)

Summary: Travel journals contain valuable information for historians, and this includes those who have a special interest in the history of horology. This article, an edited version of the Dingwall-Beloe Lecture delivered at the British Museum on 17 November 2022, offers horological information gleaned from the travel journals written by the Frenchman Balthasar de Monconys (1608–1665), the Englishman Philip Skippon (1641–1691) and the German Heinrich Sander (1754–1782). Neither of them had practical experience or personal involvement with clocks and watches, and this article concludes with a discussion of similar documents recording travels undertaken by two men who were actively involved in the trade: the Swiss clockmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721–1790) and the English clockmaker James Upjohn (1722–1794).

Picture Gallery: An unrecorded early pendulum clock

by Richard Newman (pages 236-240)

Summary: The clock illustrated and discussed in this article was made in 1666 by Johann Koch who was the clockmaker to King Charles XI of Sweden.

Museum profile: Horology in Tokyo

by Bob Frishman (pages 241-246)

Summary: This article presents the Daimyo Japanese Clock Museum, the National Museum of Nature and Science and the Seiko Museum.

Berthoud 1759: a bibliographical note

by Anthony Turner (pages 247-250)

Summary: Examination of several copies of Berthoud’s first publication L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres : à l’usage de ceux qui n’ont aucune connoissance d’horlogerie has allowed the true second edition to be distinguished from a pirate edition that was hitherto thought to be that.

‘Unfreezing Time #18’ by Patricia Fara (pages 260-261) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

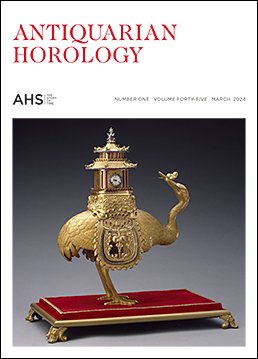

Volume 45, Issue 1 March 2024

On the front cover: More than twenty clockwork treasures collected by Chinese emperors have travelled from the Palace Museum in Beijing to be displayed in the Science Museum, London. The exhibition ‘Zimingzhong: Clockwork Treasures from China’s Forbidden City’ runs from 1 February to 2 June 2024. The clock shown here was produced by James Cox, and incorporates parts made in China. Photo © The Palace Museum

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Ellicott’s Dissertation and the Spanish Connection. With an introduction and analysis’

by Paul Tuck (pages 19–43)

Summary: An undated document written by John Ellicott (1706–1772) was in response to a request from an unknown ‘Noble Personage’ concerning the possibility of improvement in the regular going of watches. The original manuscript was lost and only known as a Spanish translation in the Biblioteca Real, Madrid. In 1957 this was transcribed by Junquera and published in a Spanish journal of horology, causing it to be recognized by Malcolm Gardner as being Ellicott’s faded original which he had acquired from the library of Percy Webster. Its contents are now revealed and give an insight into the state of watchmaking at a time when compared with the accuracy of pendulum clocks, the lack of such precision in pocket watches was beginning to be seriously questioned.

‘James or Jacob Hassenius, a clock- and watchmaker in London and Moscow’

by Keith Stella (pages 45–62)

Summary: This article examines the life and works of a Russian-born clockmaker, James (or Jacob) Hassenius, who lived and worked in London from around 1682 to 1698 and who, following the visit of Peter the Great to London in that year, then left England to work for the Tsar in Moscow as a clock- and watchmaker. Several London longcase and bracket clocks and at least two watches, all signed ‘Jacobus Hassenius’, are known to survive. As a result of some research papers written by a former colleague of the curator of clocks at The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, we are now able to trace what became of James Hassenius once he left England. The known clocks and watches signed by Hassenius while working in London are briefly catalogued in the Appendix to this article. (Read this article here)

‘Experimenting with the pendulum: the work of Tito Livio Burattini (1617–1681)’

by Augustin Gomand (pages 63–87)

Summary: The main studies related to the first pendulum clocks focus on the prototypes invented by Christiaan Huygens, described in Horologium in 1658 and in Horologium Oscillatorium in 1673, as well as on the commercial models made by Salomon Coster and reproduced by various clockmakers in Europe. However, others tried to apply the pendulum to clocks in parallel to Huygens’s work or inspired by it. The clocks resulting from this are interesting because they were conceived with an experimental and scientific purpose, to experiment with the pendulum oscillator and to test its regularity; they may present atypical layouts which deviate from the models proposed by Huygens. Several brief descriptions of such experimental clocks designed by the Italian-Polish engineer Tito Livio Burattini (1617–1681) offer an opportunity to analyze his original constructions and to understand how they fit into the scientific context of the time and are linked to the personality of this inventor. This article is part of the Simon Le Noir Project.

‘Grande sonnerie monumental clocks of Detouche and Houdin (c1855). Part 2, The great clock of the Conservatoire‘

by Denis Roegel (pages 88–96)

Summary: In the early 1850s, the clockmakers Constantin-Louis Detouche (1810–1889) and Jacques-François Houdin (1784–1860) developed a new system of ‘grande sonnerie’ for public clocks. This two-part article aims at describing this little known system. Part 1 described a new striking work patent by Detouche and Houdin, and its implementation on a clock around 1855, but that clock was unfortunately later transformed and the multiple countwheels are no longer extant. In the second part, we describe the Detouche clock of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers in Paris, installed in 1863 on the grand entrance staircase, where it is still located.

An Horologion horologically illustrated

by Anthony Turner (pages 97–103)

Summary: An horologion is a book prescribing prayers and adorations to be observed throughout the day by the faithful. The use of clock images in a Jesuit version from 1691 displays how the spiritual use of the clock metaphor continued to be employed.

‘Unfreezing Time #17’ by Patricia Fara (pages 104–106) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 148 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, Notes from the Librarian, AHS News, Letters and Further Reading.

Top of Page

Volume 44, Issue 4 December 2023

On the front cover: We don’t have records of the names of the men who wound the Great Clock of Westminster in the early days, but they have left their marks in the form of footprints worn into the ground around the clock. Photo Simon Camper.

‘Big Ben’ features prominently in the section AHS News in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Clockmaking and practical mathematics in the provinces of Britain and France, 1500–1800’

by Anthony Turner (pages 461–487)

Summary: Clock- and watch-making in Early Modern France and Britain was not exclusively an urban activity. In towns and villages throughout the provinces time-measurement by clocks, watches or sundials was required, while elaborate astronomical clocks acted as mechanical almanacs and advanced popular education. At the same time, such items displayed their makers’ skills, opening a path to income and reputation. This article is based on the AHS London lecture delivered on 9 March 2023. AHS members can watch a recording of the lecture in the website member area.

‘The Bull family of clockmakers Part 2. Randolph Bull (c. 1557–1617)’

by Adrian A Finch,Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages 488–506)

Summary: Continued from Antiquarian Horology, September 2023, 339–352. The second part of this article continues the story of the Bull family with Randolph Bull, who was John Bull’s brother and apprentice. Randolph Bull was trained in John’s workshop probably by Michael Nouwen but he worked with Bartholomew Newsam in the early 1580s and established himself independently in St Gregory by St Paul’s parish in 1582. He was appointed as royal clock-keeper in 1589 on the death of his brother. Randolph Bull’s workshop produced the earliest pocket watch bearing an Englishman’s name and trained a significant part of the watch and clock-making community of the period. His eldest son Cuthbert was introduced to the Goldsmiths’ Company in 1605 but died soon afterwards. Randolph tried to bring his son Emmanuel to take over his business, but Emmanuel displeased his father and was replaced in Randolph’s succession by Anthony Risby and Francis Foreman. Randolph died in 1617; the community trained by the Bulls would in the fullness of time become a central part of the workforce that established the Clockmakers’ Company in 1631.

‘Grande sonnerie monumental clocks of Detouche and Houdin (c1855). Part 1’

by Denis Roegel (pages 507–516)

Summary: In the early 1850s, the clockmakers Constantin-Louis Detouche (1810–1889) and Jacques-François Houdin (1783–1860) developed a new system of ‘grande sonnerie’ for public clocks. This article aims at describing this little known system.

‘John Donegan’s watch factory in Ireland’

by David Boles (pages 517–528)

Summary: In ‘The Irish Museum of Time, Waterford, Ireland’, published in the December 2022 journal, mention was made of a contemporary description of John Donegan’s watch factory, published in the Dublin Weekly Nation newspaper edition of 1 May 1858. This article offers a transcription of this interesting document, with a short introduction and some explanatory insertions.. (Read this article here)

‘Stephen Rimbault (1711–86)’

by James Nye (pages 529–537)

Summary: When the Seven Dials Trust recently decided to press ahead with erecting a plaque in Monmouth Street to commemorate Stephen Rimbault, the AHS was asked to verify his dates. What might be thought to be a trivially easy enquiry revealed that no biographical summary for this well-known maker had been undertaken previously. The following notes address this deficiency, and correct some misinformation that is regularly repeated, particularly with regard to working dates.

‘Picture Gallery: Three coach watches’

by Artemis Yagou (pages 538–544)

In this Picture Gallery we illustrate three objects from the Timekeeping collection of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, that, because of their size, may be classified as coach watches.

‘Unfreezing Time #16’ by Patricia Fara (pages 545–547) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 3 September 2023

The front cover shows the clock tower in Padua. Photo Paul Tuck.

The section AHS News in this issue contains an extensive and richly illustrated report of this year’s AHS Study Tour to Italy.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘The life and watches of William Anthony (1764/68–1844/47). Part 2, his watches’

by Ian White (pages 322–338)

‘The Bull family of clockmakers Part 1. John Bull (c. 1535–1589)’

by Adrian A Finch, Valerie J Finch and Anthony W Finch (pages 339–352)

Summary: The earliest English clock- and watch-makers came to prominence in London in the late Tudor period. One of the key families in early London clockmaking was the Bull family, several of whom were clockmakers or mathematical instrument-makers of note. This article describes the first member of the family: John Bull, a mathematical instrument-maker. We show that John was primarily a goldsmith working in jewellery who recognised the potential of the mathematical instrument trade. He employed Dutch engravers and watchmakers, including Michael Nouwen, to produce items that were sold from a workshop in the newly-built Royal Exchange. Nouwen trained Randolph Bull in John’s workshop and we consider this a key moment in the development of the London horology trade. John was appointed as royal clock-keeper, presumably after the death of Bartholomew Newsam in 1587, the first London guild member to hold the post. He worked for the Crown through two of the most eventful years in British history, serving in the royal entourage at the time of the Spanish Armada, but died only a few years later in 1589. John Bull’s workshop is the historical nexus point as we trace the training of many of the clockmakers of Stuart London back in time.

‘ ‘Forever addicted to the mechanical’– Rudolf Kaftan and the Vienna Clock Museum’

by Tabea Rude (pages 353–368)

Summary: The Vienna Clock Museum was founded in 1917 in the middle of the First World War. Its nucleus was formed from the collection of a single collector, Rudolf Kaftan (1870–1961), who would shape the museum’s fate and character for the next forty-four years. This article, based closely on the Harrison Lecture delivered to the Clockmakers Company in September 2022, charts the evolution and development of the museum in tandem with examining some facets of Rudolf Kaftan’s life.

‘The conservation treatment of a refracting telescope on a universal equatorial mount c. 1741, signed Hindley, YORK’

by Timothy M. Hughes and Matthew Read (pages 369–376)

Summary: Henry Hindley (1701–1771), clockmaker, watchmaker and maker of scientific instruments, was born in Wigan and worked in York from 1731 until his death. Hindley was the maker of the world’s first equatorially-mounted telescope, which can now be seen in Burton Constable Hall, East Yorkshire. The Hindley telescope is the subject of this article; the conservation ethos and methods described in the full report are relevant to the conservation of a wide range of historic dynamic objects, including clocks and watches. The communication of conservation processes is also, we believe, important to the wider understanding of time-finding and time-telling collections. (Read this article here)

‘From oil painting to enamel watch case: a latter day Metamorphosis’

by Anthony Turner (pages 377–380)

Summary: Combined use of documents and surviving paintings permits the process by which an original scene was transferred from a painting to a watch case to be illustrated, and confirms an attribution that has been contested.

There is also a 2-page note ‘BEHIND THE STARS — a free app using interactive versions of astronomical instruments to comprehend the heavens’, by Frederik Nehm & Michael Korey, and an announcement of a Special Sale of R.T. Gould ephemera for AHS Charitable Funds.

‘Unfreezing Time #15’ by Patricia Fara (pages 392–393) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 2 June 2023

The front cover shows the sailor jack prior to re-installation. Date thought to be c. 1950, photographer unknown. Winter family collection.

For more information see the article on Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire, in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘The ring-watch of Emperor Charles V’

by Víctor Pérez Álvarez (pages 169–178)

Summary: The miniaturization process in horology began in the fifteenth century and reached its zenith in the first half of the sixteenth century, when the earliest known ring-watches with striking mechanism were made.

The first watches of this type were very rare objects of prestige and often presented as diplomatic gifts. Charles V, the Dukes of Urbino, the Pope, and Suleiman the Magnificent were probably the first owners of ring-watches. In this article we publish four letters dated 1538 about Charles V’s ring-watch which shed further light on the history of these objects.

‘Summe Dyrections towards the makinge of a smale watche, of brasse’ – A guide to watchmaking techniques in the seventeenth century

by David Thompson (pages 179–206)

Summary: It was not until the end of the seventeenth century that books were published to explain how clocks and watches actually worked. An anonymous manuscript among the Evelyn Papers in the British Library, which pre-dates those publications, describes in some detail how a watch was made. This article discusses the possible authorship and the contents of this manuscript, and offers an annotated transcription.

‘The life and watches of William Anthony (1764/68–1844/47). Part 1, his life’

by Ian White (pages 207–222)

Summary: William Anthony is not well known today, but his watchmaking career c.1790-1805 was conducted with flair and great originality. He made a significant fortune exporting his watches to China, and spent the rest of his life losing it. His life outside watchmaking was centred around the complex inter-relationships between his sister Elizabeth, the chronometer makers Grimalde & Johnson, the chemist John Huskisson, and Jane Luson, a wealthy widow.

‘Peter Litherland’s patent watches and their successors. A fine-grained history of rack lever watch production’,

by Michael Edidin (pages 223–230)

Summary: Taking a close look at the production and distribution of watches with Litherland’s patent escapement, I argue from the evidence of existing watches that Litherland did not license his patents, as is often stated. Rather, in the 13-year lifetime of the patents, the Litherland shop produced and fitted rack lever escapements for watches signed by others, including Robert Roskell. Using counts of existing rack levers, I also show that Liverpool (and London) production of rack lever watches did not expand until after the Litherland patents had expired. Rack lever production declined after other new escapements, notably Massey’s, were developed, though it persisted well into the era of detached lever escapements. (Read this article here)

‘Coming home: a tavern clock by John Dewe of Southwark, active 1733–1764’

by Martin Gatto (pages 231–236)

Summary: This article traces the history of a tavern clock, made around 1735 by the London maker John Dewe, from its appearance at an exhibition in 1949 to its repatriation from Australia in 2022; its history between c. 1735 and 1949 is unknown. It was then restored, and the treatment is discussed in some detail.

‘Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire: its history, context and conservation. Part 2. Jacob Winter – his later life and legacy 1865 to 1904’

by Steve and Darlah Thomas (pages 237-249) [continued from Antiquarian Horology March 2023, pages 91–100]

‘Unfreezing Time #14’ by Patricia Fara (pages 250–251) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, Unfreezing Time, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.

Volume 44, Issue 1 March 2023

The front cover shows a detail of a rear view of jacks and bells, showing fixings, from Sir John Bennett’s shopfront on Cheapside, London, re-erected at the Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan, USA in 1930. Photo © Mark Frank, 2018. For more information see the article on Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire, in this issue.

This issue contains the following articles:

‘Prototype lantern clocks. Part 2: Newly discovered clocks’

by John Robey (pages 23–33)

‘Two precision clocks by William Nicholson’

by Jonathan Betts (pages 34–42)

Summary: This article describes the two known clocks signed by natural philosopher and scientific journalist William Nicholson (1753–1815). For a short summary of the life and work of this significant figure of the Enlightenment, see the Notes from the Librarian in this issue. (Read this article here)

‘An early demonstration of the spiral balance spring by Isaac Thuret’

by Rory McEvoy (pages 43–55)

Summary: In 2009, an unusual seventeenth-century table clock by Parisian clockmaker Isaac Thuret came to light in a French auction room. The unique shape of the case and empty holes on the movement plates strongly suggested that the clock had originally been made to demonstrate the then-new technology of the spiral balance spring. Through study of the clock, its restoration, seventeenth century sources, and recent scholarship, the article presents the dispute over patent rights to the spiral balance spring and opens a discussion on methodologies for dating religieuse clocks of the 1670s.

‘Daniel Quare (1648–1724): Yorkshireman, activist, Quaker horologist and businessman’

by Ann McBroom (pages 56–81)

Summary: Excellent accounts already exist of Daniel Quare’s horological legacy; 1, 2, 3 this paper is intended as a supplement. A painstaking search for a birth record for Daniel in Somerset, where he reportedly was raised, yielded nothing. 4 The evidence presented here is that he was a Yorkshireman, baptised Daniell Quaer at All Saints Wistow on 1 January 1649, the son of Robart Quaer. 5 My hope is that this will unlock new information about Quare’s early life and where and with whom he trained. Daniel Quare was a life-long activist. He worked tirelessly to achieve full toleration for Quakers, but his activism was far broader and included efforts to combat societal injustices in Britain and overseas. The current paper considers how, as a Quaker, he may have navigated his personal and business options.

‘The Lepaute tower clock of the future King Louis XVIII in Versailles (1780)’

by Denis Roegel (pages 82–90)

Summary: The clock described in this article is one of the earliest known tower clocks made by Lepaute, and the oldest such clock known with a pendulum length adjustment. It was installed in 1780 in a private mansion in Versailles owned by the future King Louis XVIII. It is in storage in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Strasbourg.

‘Jacob Winter’s shopfront in Stockport, Cheshire: its history, context and conservation. Part 1: Jacob Winter 1865 to 1904’

by Steve and Darlah Thomas (pages 91–100)

Summary:Jacob Winter (1865-1935) was a first-generation watch, clock and jewellery retailer who began trading in Stockport around 1890 and whose business continued for a century. His shopfront was adorned with a projecting clock and three automata which chimed ting-tang quarters and struck the hours. Intended to draw public attention to the business, the daily displays did just that and became the town’s major attraction. What inspiration lay behind this? We will consider the possibility that sight of John Bennett’s emporium on London’s Cheapside inspired a young boy, and the coincidences of location and selection of clockmaker which came into play. We look at two clocks made thirty years apart to perform similar tasks and at the recent efforts to conserve one clock’s place in the life of a northern town.

‘A sphygmochronograph for registering the pulse’

by Thomas Schraven (pages 101–105)

Summary: An ongoing hunt for unusual short-time measurement devices by the Jaquet firm led to the discovery of an early clockwork item for recording the human pulse. This article describes its origins, development and operation.

‘Unfreezing Time #13’ by Patricia Fara (pages 106–107) (Read the whole series of articles here)

The issue totals 144 pages and is illustrated mainly in colour, and is completed by the regular sections Horological News, Book Reviews, AHS News, Notes from the Librarian, Letters and Further Reading.