The AHS Blog

Plans for an important clock

This post was written by James Nye

St Luke’s church (c.1825) in West Norwood, London, has an extremely fine clock (c.1827) by Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy, costing some 3 per cent of the budget for the church and the equivalent of several hundred thousands of modern pounds.

It is probably the first flat-bed turret clock in England, embodying ideas developed by Vulliamy on recent Continental travels.

Vulliamy’s clocks were substantially more expensive than those of his competitors, but he boldly claimed they would outperform and outlive cheaper alternatives. While it may not presently be working, a recent survey of St Luke’s revealed a very high quality clock, still in remarkable order.

Clock towers are deeply inhospitable environments, cycling in temperature between plus 40 degrees C and falling below zero – with humidity varying from low to 100 per cent over time.

The natural modern trend to move away from weekly attendance by a clock winder necessitates auto-winding, but St Luke’s system has failed.

There are further problems. Vulliamy’s slate dials were replaced with opal glazed versions in 1928, but the putty fixing of the panels has dried to a cement-like hardness, and the lack of flexibility allows for cracking of the glass, as the cast iron tracery expands and contracts.

Moisture can creep in, leading to ‘rust-jacking’. Several panels failed long ago, being replaced in wholly unsuitable plastic, offering a patchwork impression at night. Many other panels are cracked, and the eventual failure of the glazing is certain, while the clock room suffers.

The church is now launching a substantial project to repair the clock, add new auto-winding and auto-regulation, but, significantly and most expensively, also to repair all four dials with new opal glass.

This is a project of great significance to the community of West Norwood – the clock is highly visible and a symbol of local civic pride over two centuries.

Action and pressure from the local community has led to the present proposals for a project to restore the clock to function. Fortunately, a number of different members of the Society have also been offer to valuable input and assistance, and fundraising is well underway.

Fire! Fire!

This post was written by James Nye

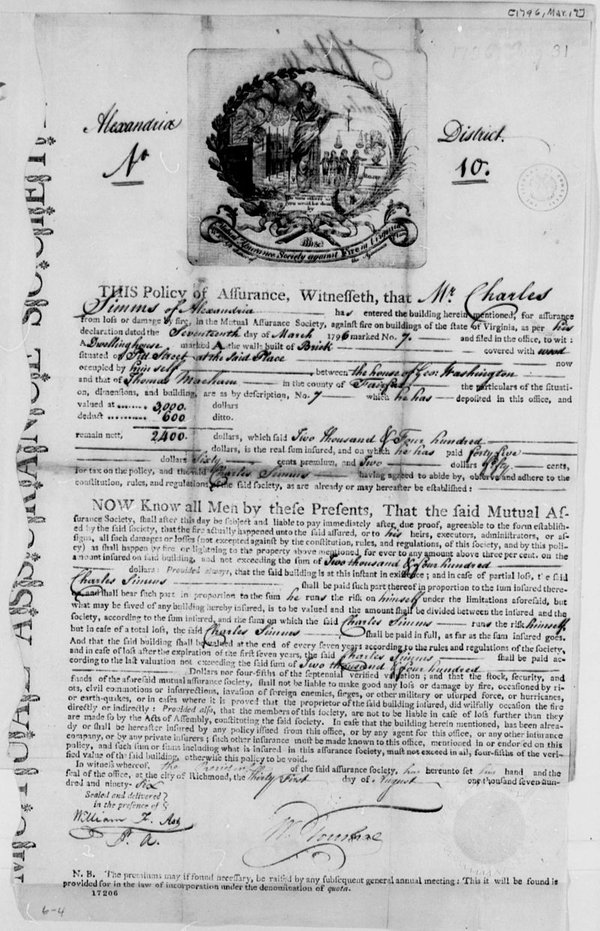

The AHS has launched a fascinating new research resource for its members – a series of searchable fire insurance records, covering the period 1710 to 1863.

Over many years, the late Roger Carrington (1948–2005) manually transcribed fire insurance records now held at the London Metropolitan Archive (LMA), and his work has been digitalized and added to the AHS web-site.

The LMA catalogue describes the holdings of a ‘substantial, if incomplete series of fire policy registers’ which survive for several insurance companies, including Sun Life (from 1710 to 1863), and Royal Exchange (from 1754 to 1759, and 1773 to 1863).

Roger focused on the policies of clockmakers and watchmakers, and related trades.

We have created downloadable and searchable pdfs. The key benefit is the digital searchability of all six thousand one hundred and twenty records involved.

What can one discover?

Well, as the catalogue notes indicate, ‘Where fire policy registers exist, they generally include the following information: policy number, name of agent/location of agency; name, status, occupation and address of policy holder; names, occupations and addresses of tenants (where relevant); location, type, nature of construction and value of property insured; premium; renewal date; and some indication of endorsements […] Sun Fire insurance policies were renewed after five years at which time a new policy was issued under a new number.’

The data are of great interest to the horological researcher for a wide variety of possible reasons.

The records can be searched for the name of a clockmaker, watchmaker or anyone involved in related trades. If the relevant name appears, the details of a policy can then be reviewed – potentially revealing new and interesting contextual material (e.g. verifying an address for a given date range, indicating prosperity or lack of it, etc.)

The records could be interrogated in a different way, for example by location, occupation or street name.

Many will find the searchable pdfs sufficient, in simply locating information to be found in the main policy transcriptions. However, some may wish to do more with the data, and to this end we have provided an index in Excel, which will allow for more sophisticated searches of the data.

This valuable resource is only available to AHS members, so do join up if you think it might be useful in your research. AHS membership is terrific value and your subscription helps support our mission to foster the study of the story of time.