The AHS Blog

The conservation of precision horology

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A few weeks ago I attended a fascinating international three-day conference on the conservation of historic regulators and chronometers, hosted by the curatorial and conservation staff at Palermo Observatory in Sicily, part of the INAF group (Instituto Nationale di Astrofisica) of Italian observatories, all of which have historic collections of instruments and timekeepers.

The lectures, which were presented by specialist curators and conservators from Italy, UK, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, covered a great range of horological subjects from philosophical preservation, practical conservation of collections and a more general discussion of the care and preservation of these especially vulnerable objects.

Although the various papers reflected quite different perspectives, all the speakers found common ground on the principles of care and spoke with one voice on the aims of their roles as custodians of our historic collections.

A particular aim of the conference, discussed in depth in the final group meeting, was to formulate a common set of guidelines for future curators and conservators, and an internet forum was then established to continue the dialogue in future.

The hosts at Palermo Observatory, Ileana Chinnici and Maria Carotenuto, to whom we were especially grateful for organising the event, were particularly keen to seek advice from delegates on formulating a programme of care for the fine collections at Palermo. This might then apply to all the historic precision instruments in the Italian observatories under INAF.

We learned some fascinating statistics:

-- these instruments represent 80 per cent of the astronomical heritage in Italy, and 10 per cent of these objects are timekeepers of one kind or another;

-- in all the various observatory collections there are 53 clocks, 31 chronographs and 12 box chronometers;

-- 25 per cent of the horological material is of British manufacture, 20 per cent is Swiss, 13 per cent is Austrian/German, 7 per cent is French, and 35 per cent is Italian.

Naturally the regulators at Palermo formed the focus of much interest and discussion during the conference, and what fine things they are! The stellar list of makers includes Mudge & Dutton, Janvier, Vulliamy, Cumming & Grant, Frodsham, Dent and Riefler.

Palermo Observatory had been founded in 1790 with Guiseppe Piazzi as its first astronomer. It was Piazzi who, on a visit to London and Paris in the late 1780s, commissioned the regulators from Mudge & Dutton, Cumming & Grant and Janvier as the first timekeepers for astronomical use at Palermo.

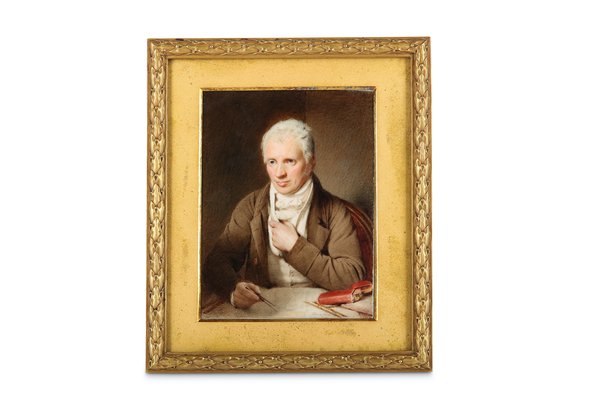

Having recently studied and written about the works of Alexander Cumming (Antiquarian Horology, March 2022), I found the example by Cumming & Grant, which has Cumming's own form of gravity escapement, of particular interest. It is very similar to the regulator signed by Grant only, in the Clockmakers' Company Museum in the Science Museum, London, both clocks being of superb quality.

A really interesting and valuable three days; there will hopefully be a chance to return soon to study this fine collection more closely.

The various rooms in the historic building now form the museum of the observatory, which can be visited in person or virtually.

Ringing in the New Year

This post was written by Andrew Strangeway

As a clockmaker, or practising horologist, there is one particular moment while waiting for a clock to strike when time seems to slow down.This moment is more daunting when the streets outside are lined with 100,000 people and millions more are watching live on television, and streaming, waiting to hear the clock chime.

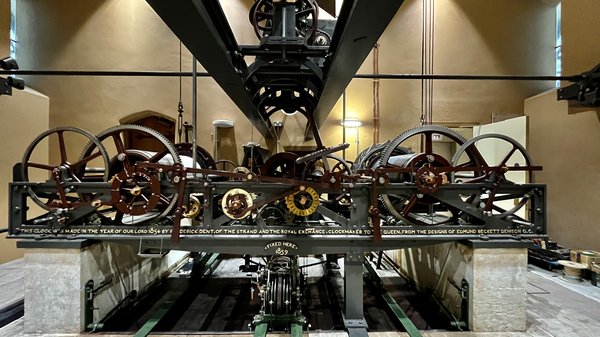

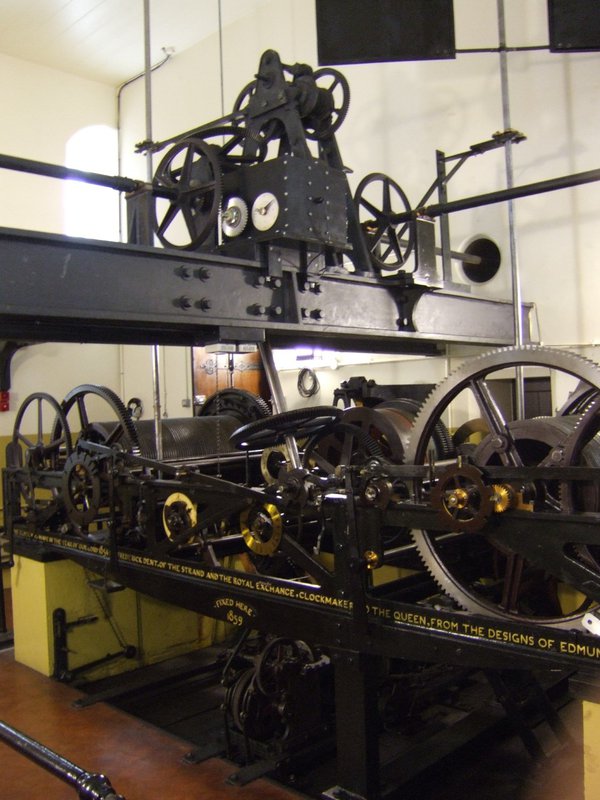

On December 31st it all comes down to a single moment, when the nation watches and waits for Big Ben to ring out and signal the start of the new year. Behind the scenes, however, months of preparation go into ensuring that this first hammer-blow falls precisely on time. Besides the installation of additional broadcast equipment, regular servicing, and thrice weekly winding there is also timekeeping: ensuring, literally, that the clock stays on time.

In the months leading up to the end of 2023, the timekeeping of the Great Clock was a core focus. After the break of six years during the servicing of the clock and tower, the twice-daily live chimes finally returned to BBC radio airwaves on November 6th. This New Year marked the 100th anniversary since the bells were first broadcast live for New Year’s Eve. It was a matter of pride that the clock should perform well and strike on time.

When it was first installed, the Great Clock was, by some margin, one of the most accurate public clocks in the world. The original specification for the clock set down in 1846 by George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, required that ‘the striking machinery be so arranged that the first blow for each hour shall be accurate to a second of time’. As clockmakers our job is to ensure that the clock remains true to this original purpose. To our advantage, we have highly accurate timekeepers to compare the Great Clock against and, armed with this information, we can regulate the pendulum carefully and actually comfortably exceed the original target for accuracy.

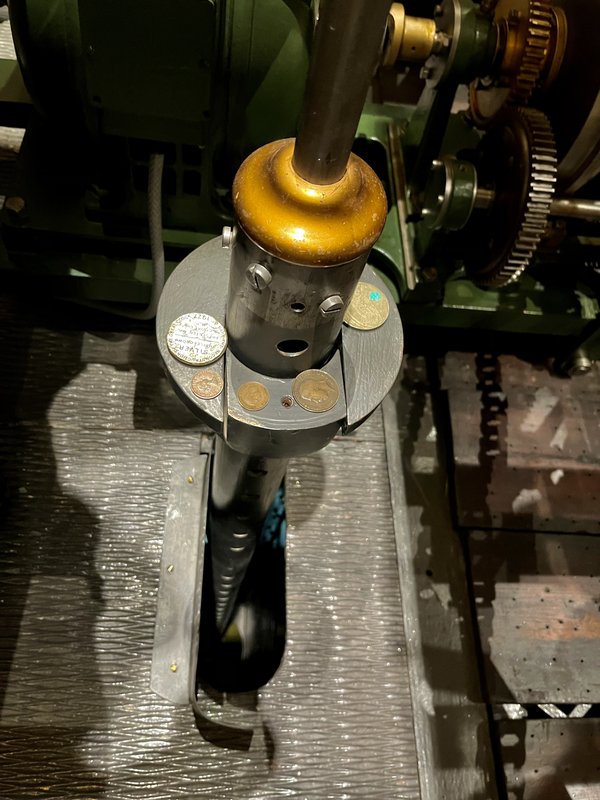

Since starting at the Palace of Westminster in August 2023, I have implemented the use of a new custom-made timer to increase the accuracy of the timing of the first hammer-blow of the hour and an improved regimen of regulating the rate of the clock’s pendulum. The core mechanics of regulation remains as ever: the placing or removing of weights, in the form of old currency, on a small platform partway down the length of the pendulum rod. Famously, one pre-decimal penny added speeds up the clock by about 2/5th of a second over 24 hours. These are a little too weighty and the adjustment too coarse if one is aiming for a finer degree of accuracy. I have begun using ha’pennies and farthings for regulation, kindly lent for the purpose by my colleague in the clock team, Ian Westworth. These speed the clock up by about a quarter of a second a day and a tenth of a second a day respectively.

In the final days running up to New Year’s Eve I was at the top of the tower, on the hour, throughout the day to take a timing reading from the strike and to make small adjustments to bring the clock precisely to time. As luck would have it, on the evening of the 30th we experienced heavy winds, which buffeted the tower and were enough to throw the clock out by 0.2 seconds by the morning of New Year’s Eve. I was able to correct for this by the evening. Midnight came and Big Ben struck, and the view of the fireworks from the top of the Elizabeth Tower was astounding. It was awesome to see the fireworks perfectly synchronised with the strike of the bell.

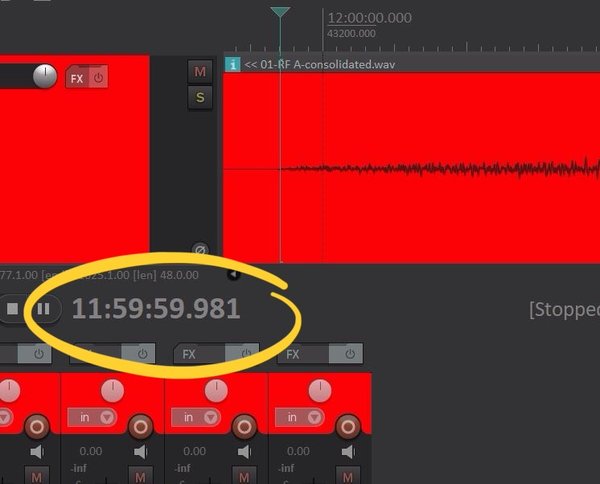

My timekeeping efforts were rewarded when we measured the timing of the strike from the sound recording compared with a GPS clock – these results were generously provided by Mark Powell of DeltaLive. The result was that Big Ben struck midnight at exactly 23:59:59.981, within less than a fiftieth of a second of midnight. That’s less than a fifth of the time it takes to blink your eyes. I must confess to being rather pleased with that!

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

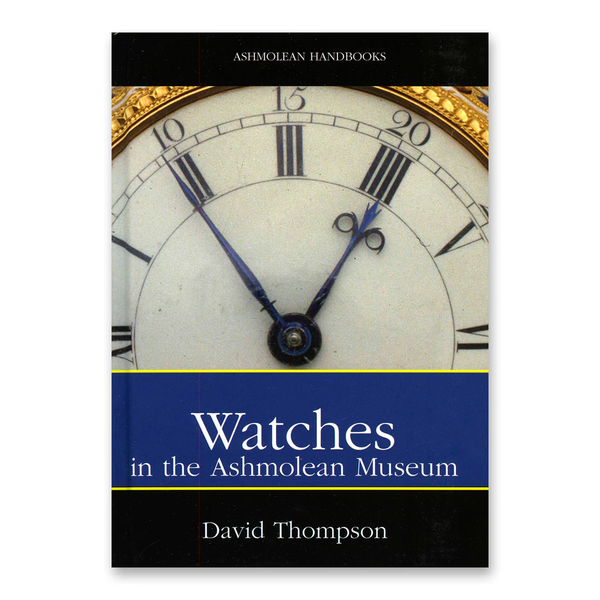

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

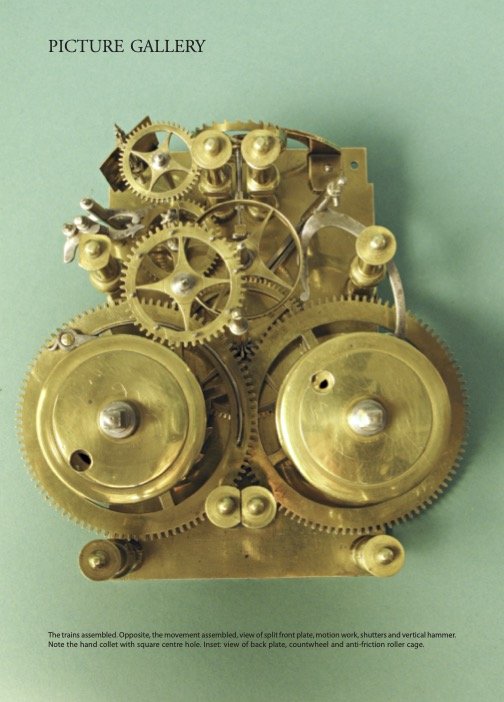

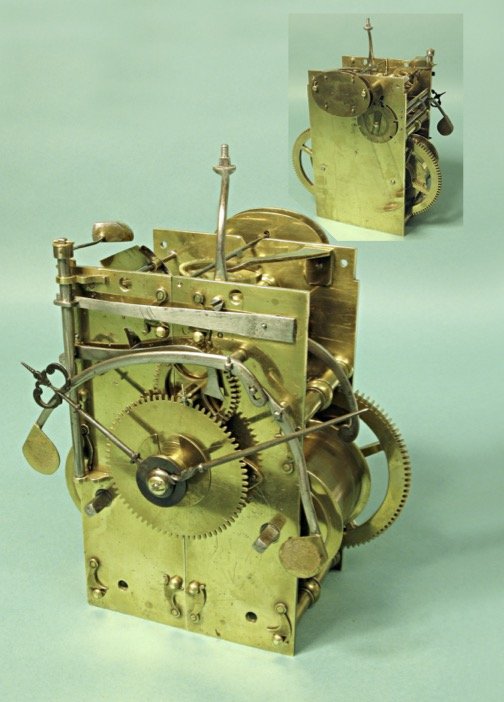

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Light among the lanterns

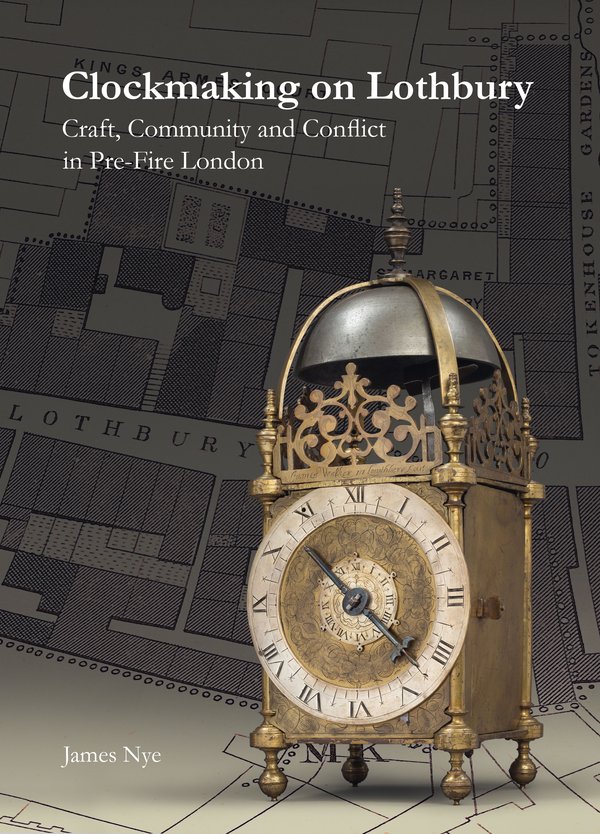

This post was written by James Nye

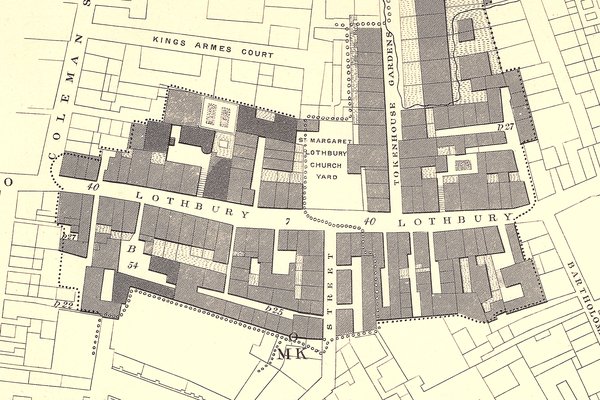

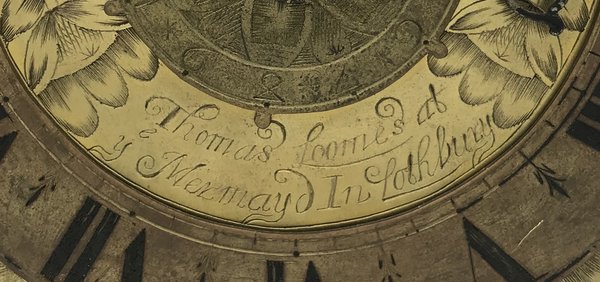

I used to walk regularly from Cannon Street tube station to the Clockmakers' Company office in Throgmorton Avenue, and on the way would walk down the west flank of the Bank of England, turn right and cross over to slip down Tokenhouse Yard. One day, passing St Margaret’s Lothbury, I stopped, and looked around. It struck me forcibly that Lothbury was really short, yet I knew that a fair number of lantern clocks were signed from addresses on the street. I was intrigued. Was this like restaurants crowding together and all benefiting from increased business?

This was back in 2018, and I conceived the idea of a deep dive into the street’s pre-Fire history. It was known for its founders, and for their ‘turning and scrating […] making a loathsome noise’. Was it such a bad place? Who else lived there, and what did they do? I recruited a research assistant, Caitlin Doherty, and together we planned trips to archives and libraries, following up hunches and leads developed together.

This all resulted in a lecture we jointly gave in November 2019, but I had to jettison more than half my material to squeeze it into a decent length. Then Covid struck and the larger work languished, until mid-2022 when I dusted it down and gave it a read. I was pleasantly reminded of much, but also conscious that a lot more could be done, so I strapped on the tanks and went overboard again.

I was still frustrated that on the first attempt I had failed to pinpoint the location of the Mermaid, the best-known Lothbury address, home to Selwood, Loomes and others, and from which the first pendulum clocks were sold in London. A punch-the-air moment occurred earlier this year when I finally found archival documents that revealed its whereabouts.

The project eventually grew to a book-length treatment and I am deeply grateful to the Society for backing its publication. It has recently been rolling through the presses. You can see pages being prepared for sewing here and the cover being embossed here.

Make no mistake, this is not a technical book about lantern clocks. But it is a forensic account of the small community in which one group of remarkable makers lived. It reveals who their neighbours were and the challenges they all faced, whether against the backdrop of the Civil Wars or the poisonous smoky atmosphere. It discusses the trades in which the merchants on the street were engaged, but reveals some of the poverty close at hand. I hope that in many ways it should throw some more light around the early life of many lantern clocks. And you can order it here!

A varied horological life

This post was written by Su Fulwood

'I have to ask you, is this your actual job?' This was put to me last week while I was winding one of the clocks in the collection at Goodwood House, the home of The Duke and Duchess of Richmond in West Sussex. Well, yes it is – one of them anyway, I do a few things.

I’m a freelance collections advisor, researcher and curator, so I work with all things from costume to archaeology, but more than half of my projects are horology related. Possibly this is because clocks, as something with a beating heart metaphorically, evoke memories and stories as well as encompassing art, science, technology and history, so as an example of material culture they are multifaceted and valued.

More than anything else, clocks are firmly connected to people, their knowledge and emotions. Working with them enables me to meet and work with excellent people, to travel, and it defines the places I visit.

I’ve recently returned from a job in York that enabled me to explore the coast from Staithes to Scarborough (I suspect turret clock specialists can relate to this).

This year began with a project working with the fabulous Cumbria Clock Company and their newer recruits. I can't express how privileged I feel to work with both experienced clockmakers and the next generation of horologists.

Back at Goodwood, I have an annual presence at The Festival of Speed and The Revival exposing me to all manner of wonderful cars, their clocks and watches.

My research on women working in horology with Geoff Allnutt also leads to fantastic places. The horology community is unlike any other and this introduction is also a thank you to all at the Antiquarian Horological Society who have supported me with my work. More to come!

The National Physical Laboratory: paving the way for trusted time and frequency across the UK

This post was written by Leon Lobo

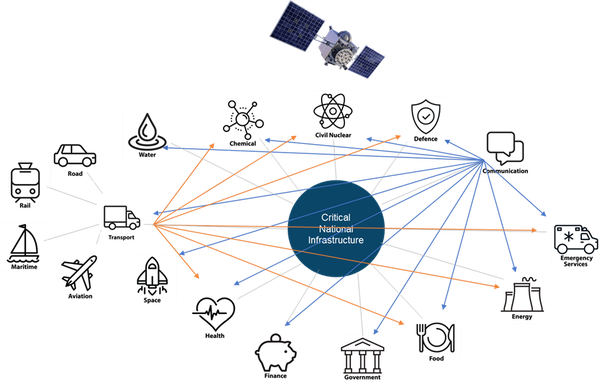

Time is the invisible utility underpinning capability across critical national infrastructure (CNI), as the basis for global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), synchronisation of 5G mobile telephone networks and the energy grid and timestamp traceability critical for trading platforms in financial services.

The world we live in is increasingly digital, with the last few years only accelerating this. We are seeing advances in communication and connectivity and society’s reliance on reliable positional, navigational, and timing (PNT) data is growing.

Many aspects of UK industry and society require increasingly precise time, whether it’s at home on our devices, the telecoms networks, energy, broadcast or in the finance industry where the time margins used are unfeasibly fine: one second for voice trading, one millisecond for electronic trading, and just 100 microseconds for high-frequency trading – all traceable to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the global time scale.

The systems, which rely on PNT signals from GNSS, are robust in themselves and have procedures in place to deal with any GNSS based system faults. However, disruptive interference can occur unintentionally and deliberately, with malicious interference a growing possibility. Potential interferences include jamming GNSS receivers, rebroadcasting a GNSS signal intentionally or accidentally, or spoofing GNSS signals to create a controllable misreporting of position.

An alternative timekeeping source is crucial to help prevent any serious impact to all of the above if something were to occur to the signals received via GNSS. They will also future proof society as we develop smart cities, autonomous vehicles and communications.

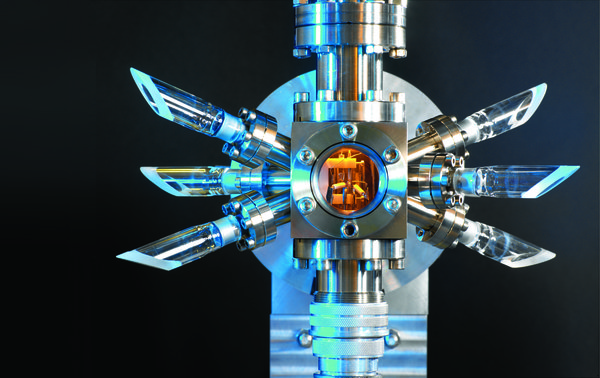

To mitigate these issues and vulnerabilities, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), through its National Timing Centre (NTC) programme, is developing an alternative, potentially primary solution for future timing. The team and I are striving to ensure that the UK digital infrastructure is supported by a GNSS-independent sovereign capability for time moving forward. I am keen that we become more aware of our dependency on GNSS and start to consider how we do things differently. Dependence by default on this space asset is no longer tenable without due consideration for resilience of operations.

The NTC programme will provide the resilience needed to protect critical national infrastructure, keeping essential services running and ensuring trust in new technologies. It will enable the UK to move away from reliance on GNSS, like GPS, for time, and leverage a range of time and frequency distribution technologies including fibre, communication satellites, and terrestrial broadcasts, alongside GNSS.

NPL’s NTC programme aims to deliver a resilient UK national time infrastructure through the building and linking of a new atomic clock network distributed geographically in secure locations. It will also provide innovation opportunities for UK companies through funding projects in partnership with Innovate UK based on a successful NPL and Innovate UK partnership model. Finally, the programme will respond to the specialist skills shortage in time and synchronisation solutions through specialist, apprentice and post graduate training opportunities.

Improved resilience will help to strengthen our society through faster, more secure internet, robust energy supplies and reliable health and emergency services. As a community that understands timing and timekeeping, I am keen to have you engaged, raising awareness of why time is important to our daily lives and what we need to consider to ensure we have resilient time for the future.

Dr Leon Lobo is Head of the National Timing Centre at the National Physical Laborartory, whose work focuses on developing and delivering the UK's national timing strategy. Having worked at NPL since 2011, Dr Lobo has led the team managing the UK’s time scale and supported on the development of NPLTime®

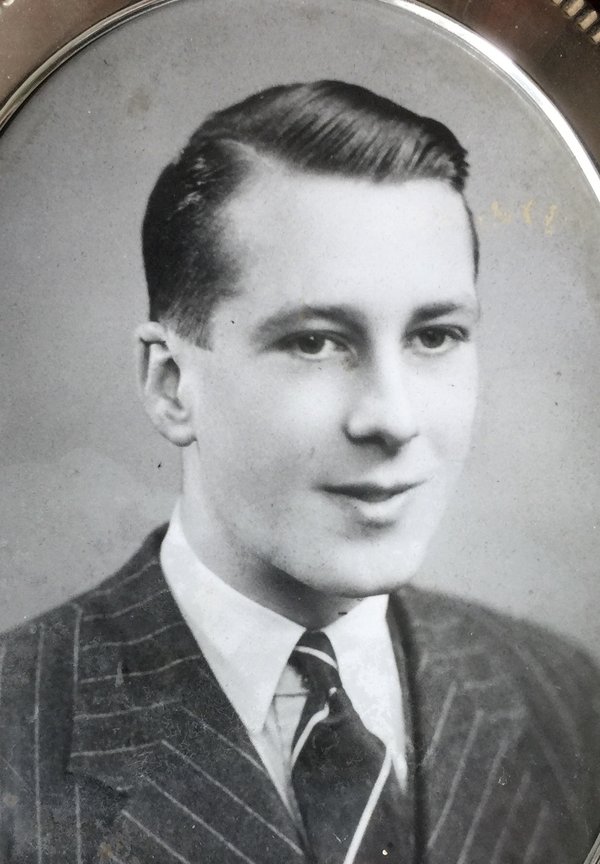

A sad commemoration

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A couple of weeks ago, I attended Bob Frishman's NAWCC conference on 'Great Horological Collectors' at the Horological Society of New York's home in New York City – a wonderfully successful and interesting event. By good fortune the date of the conference came just before a short holiday we had planned in New York, with passage home on the Queen Mary 2 – a delightful way to cross the pond.

When planning the trip I realised that, by a rather extraordinary coincidence, during the transatlantic crossing there would occur the 80th anniversary of a family tragedy, played out in those very waters.

My Uncle Pat – my mother's brother – was serving on a merchant troop ship, the MV Abosso. On the evening of 29 October 1942, when the ship was travelling alone in the North Atlantic, it was torpedoed by a U-boat and sunk. 362 of the 393 passengers and crew lost their lives, including Uncle Pat, who was just 23 and had married only a few weeks before.

Just one lifeboat survived with 31 souls to tell the tale, some of them Navy officers who were aware of the detail of what happened.

The reason for telling this sad tale in an AHS blog is that there were two critical horological elements to the tragedy.

About 6 p.m. that evening, the master of Abosso, Captain Reginald Tate, became aware the ship was being tailed by a U-boat – U575, commanded by Kapitan-Leutnant Gunter Heydemann (1914–1986), as it turned out. The ship's crew was able to detect the submarine using ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) echo-sounding to determine the sub's bearing and distance, the latter by using an ASDIC chronograph.

The watch has a high frequency sweep-seconds hand on a dial recording up to six seconds, the time between transmission of the sound pulse and the echo determining the distance of the sub from the ship.

Having established precisely where the sub was, the ship's master had to decide what to do.

An option was to go full steam ahead and try to out-run the submarine, which would normally be possible – a submerged submarine makes much slower progress, though at a maximum speed of 14.5 knots, the Abosso was not a particularly fast ship.

The alternative was to adopt a 'random' zig-zag course so the U-boat could not predict the ship's position accurately enough to make it worth firing torpedoes at it, though zig-zagging naturally slowed down the progress of the ship considerably. The practice did generally work well, if maintained long enough, as U-boats had limited quantities of fuel and eventually had to head off for a rendezvous for refuelling.

Deciding not to try and out-run, but to zig-zag, the Abosso brought into action its zig-zag clock, a part of the navigational equipment on the bridge of WW2 merchant ships at the time.

A fairly standard ship's bulkhead clock is adapted to have an electrical contact at the tip of the minute hand, and round the periphery of the minute track on the dial is a metal ring with a number of moveable electrical contacts.

Each time the minute hand touches a contact it closes a circuit and a bell rings in the wheelhouse informing the crew to change course one way or the other.

If in convoy with other ships it is of course vital that all the ships adopt precisely the same agreed pattern of zig-zags, and when the instruction to zig-zag is given, the whole convoy would be signalled a secret code for the pattern to be used. The contacts on all the ships’ clocks would then be adjusted accordingly and zig-zagging would begin at a specific time, thus foiling the U-boats' attempts to align torpedoes with a target ship.

The log of U575 has survived, so we can also follow what happened from the U-boat’s perspective. Heydemann, a much decorated Commander in the ‘Brandenburg’ wolfpack in the North Atlantic, sighted the Abosso about 6 p.m. that evening. He was running low on fuel but decided to try and attack. Realising he was being traced, he went deep, out of reach of the ASDIC, but followed from a distance until he was nearly out of fuel. At that point, thinking they had lost the sub, Abosso’s master made the fatal decision to stop zig-zagging. Realising this, Heydemann risked running out of fuel and moved closer to the ship to attack.

Reading the U-boat's log today, and comparing with the U-Boat Commander’s Handbook (available as a translated reprint as E. J. Coates (translator), The U-Boat Commander’s Handbook, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, 1989) one discovers this was a textbook operation.

At 22.13hrs, Berlin time, one of the middle torpedos of four directed at the Abosso in a fan pattern struck the ship virtually amidships. The U-boat surfaced to inspect the target and Heydemann recorded seeing lifeboats being launched. One more torpedo was fired into the ship to deliver the coup de grace, and about half an hour later Abosso sank, U575 then departing to rendezvous for refuelling.

The one lifeboat which survived was picked up on 31 October by HMS Bideford, one of a convoy forming part of 'Operation Torch', heading for North Africa but, in the heavy seas at the time, no other lifeboats or survivors were ever found.

On the evening of 29 October this year, exactly 80 years later, and as close to the location of the Abosso’s sinking as I could estimate, I sneaked a centrepiece flower arrangement from our table after dinner and, against Cunard’s strictest rules, cast them into the sea at the stern of the ship.

A timekeeper had shown Abosso where the danger was, and the other timekeeper should have saved them. It is a sad thought that if only Captain Tate had left his zig-zag clock running just a little longer, the U-boat would have had to leave and 362 lives would not have been lost.

R.I.P. Uncle Pat.

Clocks in Lisbon

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Any horologist visiting Lisbon will want to visit the Casa-Museu Medeiros e Almeida, situated just off the majestic Avenida de Liberdade: https://www.casa-museumedeirosealmeida.pt/

It is the house where the Portuguese businessman António Medeiros e Almeida (1895–1986) lived and which he filled with his private collection of objects of decorative arts, including a collection of clocks and watches. It opened as a museum in 2001.

As explained in the catalogue, which I reviewed in Antiquarian Horology in December 2019, it 'consists of a core of about 650 items. [...] The timepieces cover a period of five centuries and are from France, England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Portugal, Russia, China and Japan'. A special gallery was created for them, but clocks are also found in many other rooms.

However, I want to direct you to two other clocks elsewhere in the city.

The first is in the Military Museum, a distinctly old-fashioned – but to me rather inspiring – place; some photos can be found on http://www.exercito.pt/pt/quem-somos/organizacao/ceme/vceme/dhcm/lisboa. On display in one of its enormous rooms is a turret clock with a plaque explaining (I translate from the Portuguese):

'Constructed in Lisbon in the 18th century by the clockmaker F. Baerlein, it was the only turret clock in the neighbourhoods of Santa Apolonia, Santa Clara, Alfama, and surroundings. It commanded all the clocks in the various establishments of the Royal Armoury of the Army, and also serving the population of the nearby areas as well as the crews on the ships on the river Tagus. After being struck by a grenade in May 1915, it stopped functioning. It was repaired in March 1957 […], which the staff of the Military Museum have marked with this plaque.'

A web search found nothing on the maker. What I did find was a photo of the base of a lamp post in Lisbon with the name F. BAERLEIN. Clearly later than the clock movement, but then, perhaps Baerlein had successors in the city?

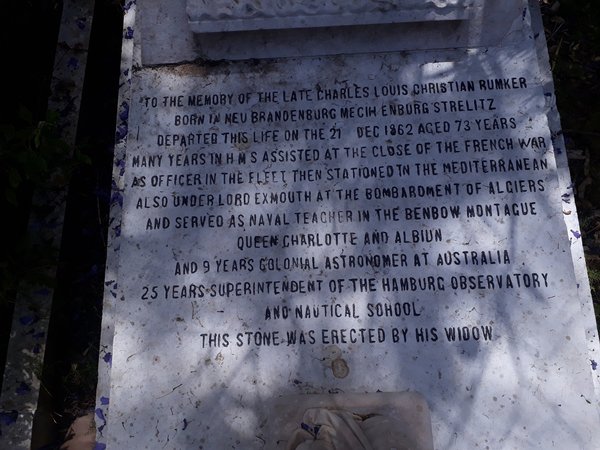

For the second clock, one must enter the beautiful British Cemetery https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/ located opposite the Estrela Park. Tourist guides invariably single out the memorial to the author Henry Fielding (1707–1754), best known for his novel Tom Jones. But to me of far greater interest is the memorial erected for the German-born Charles Louis Christian Rümker (1788–1862) https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/interesting-monuments which was the subject of an article by Julian Holland in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society No. 77 (2003), pp. 32-35.

Rümker served as colonial astronomer in Australia and later as superintendent of the Hamburg Observatory and Nautical School, and the monument shows the tools of the astronomer, including a clock.

While funerary monuments often show an hour glass, symbol of the passing of time, the representation of a clock is certainly rare, perhaps even unique? I would be interested if anyone knows other examples.

The humpback carriage clock

This post was written by William Oke

I have just finished studying on the Horology undergraduate course at Birmingham City University. For my final project, I built a humpback carriage clock and this project allowed me to research surviving examples of these to inform the design, gathering as much information as I could to create a record of those clocks. These are some of my findings.

Abraham Louis Breguet and his son, Antoine-Louis, produced many fine travel clocks including the silver-cased ‘pendule portiques’ that were sold between 1812 and 1830 [1]. Features that are included in nearly all humpback carriage clocks can be traced back to these, including silver engine-turned dials, Breguet’s iconic hand style and a number of complications necessary for travelling such as alarm, calendar work, and moonphase for travelling at night. I have been able to find records of eight of these in various collections.

There are also contemporary examples by the brothers James Ferguson Cole and Thomas Cole. During his life, Cole was called the 'second Breguet' [2]; he made several complex humpback carriage clocks with retrograde astronomical work; the earliest example is from the year of Abraham Louis Breguet's death, 1823 [3]. There is a detailed description of this clock in the first volume of the Horological Journal from the time, which also states seven more were made in the subsequent 30 years [4].

The English tradition of producing these clocks was continued by the London clockmaking firm Jump. The earliest example I have been able to find was sold by Ben Wright, hallmaked 1878 [5]. This clock was made for Francis Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke, and three further humpback clocks were ordered from Jump by the Baring Bank partners Barons Northbrook, Ashburton and Cromer.

Until this Revelstoke example appeared on the market, the only other of these four whose whereabouts was known was the one made for Ashburton, which came up for sale at Sothebys in 1998. Interestingly, the Ashburton clock was described in a letter to Colonel R. Quill from A. Hayton Jump (great-grandson of the company's founder, R. Jump), who designed 'the last dozen' of these Jump humpback carriage clocks:

“the first of these clocks was made for a Lord Ashburton of the Victorian period before I was in the business. It cost the firm a load of money in time and trouble, for so many men had to make so many parts (the man that made the hands couldn’t do anything else, etc. etc.). My father presented the bill to Lord A with trembling hands and apologised for the high charge. Lord A took the bill and wrote out a cheque at once for double the amount charged on the bill!!! And expressed his appreciation.” [6].

The most recent examples of humpback carriage clocks were produced in the mid-20th century, firstly by Philip Thornton who made several in the immediate postwar years including one that was commissioned by Charles Frodsham & Co. to be presented to Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (who was also in possession of the Breguet pendule portique, No. 2806) [7]. It is likely the last humpback carriage clock was made by Quill and J.S Godman in 1963, which was based on the clocks by Thornton.

These historic examples are rare but have been seen to come up for sale fairly regularly; there is no doubt that their pleasing design and the fine craft skill they display leave them as popular today as when they were first made.

Footnotes:

- Daniels, G., 1975. The Art of Breguet. 2021 ed. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, pp. 78-79.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, p. 112.

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, pp. 134-135.

- Ben Wright Clocks Ltd, 2016. Jump, London. https://www.benwrightclocks.co.uk/clock.php?i=105 [Accessed 3 May 2021].

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd, pp. 289-90.

- The Royal Collection Trust, n.d. Carriage clock 1947. https://www.rct.uk/collection/2943/carriage-clock [Accessed 18 April 2022].

Inspiring people with horological collections: a guide’s perspective

This post was written by Robert Lamb

Since October 2015, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection of clocks, watches and associated objects has been displayed in its new home at the Science Museum, where it is accessible to the public whenever the Museum is open.

I have been conducting 60-minute tours of this wonderful historic collection on a monthly basis since July 2019. Despite needing to pause during the pandemic when the museum was closed, myself and the other volunteer guides have been back up-and-running since October 2021 and we hope that the frequency of the tours will increase as more volunteers join the team.

So, what happens on my tours?

Firstly, I introduce myself to the group and enquire if anyone has any specific interests. Participants are a pretty eclectic mix of those who, by chance, saw the notice at reception, those who came especially to see the collection, inquisitive tourists, and passers-by who show an interest and I cajole to join!

I then explain that we will not cover the whole collection, but will be honing-in on specific objects and groupings or significant topics and people.

I always like to give a short introduction to cover the origins of the collections, history of clockmaking and development of London’s Livery Companies.

Having gauged the mood and interest of the group (not forgetting that children may need entertaining too!), we often start with the introduction of domestic clocks in Europe and London, followed by the later need for more accurate timekeeping. Often, we look at the introduction of the pendulum and I talk about the development of clocks in London with the knowledge brought back by John Fromanteel. We are regularly drawn to John Harrison and his fight for recognition to win the Longitude Prize and then become fixated by H5!

There are so many tales to tell of the many objects we encounter. I love the one of an early Master of the Company, whose role was to keep the Company chest (which contained the silver and significant documents) at home during his tenure, but couldn’t get it through his front door!

No two tours are ever the same, which gives me great pleasure and I hope it does this for the participants.

Joining a tour is the only way to see what actually happens – visit the fabulous collection yourself and soak up the wonders of such a diverse horological history!

The clock and watchmakers of Kilwinning

This post was written by Heather Upfield

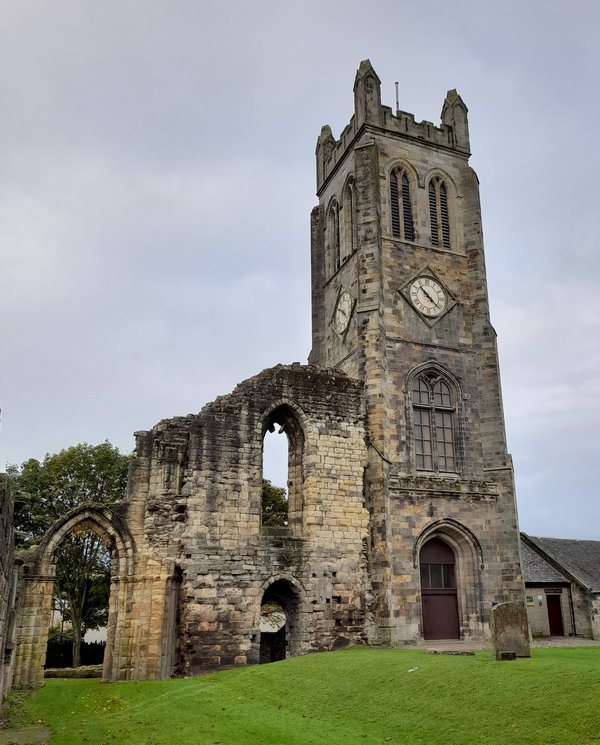

Kilwinning is a little town in south-west Scotland, which grew around the twelfth century Abbey (now in ruins). Following the collapse of the one remaining medieval tower in 1814, a new Abbey tower was built in 1816. James Blair, Kilwinning clockmaker, was commissioned to make the turret clock. As an interested local resident, I undertook research into James Blair for Kilwinning Heritage, in 2019.

The project grew exponentially, with a study of Whyte’s (1) compendium of around 8,000 people involved in clockmaking in Scotland. I discovered that James Blair was not the only Kilwinning clockmaker. There were eight men providing an almost unbroken stream of clockmakers in Kilwinning, from the mid-eighteenth century into the early twentieth:

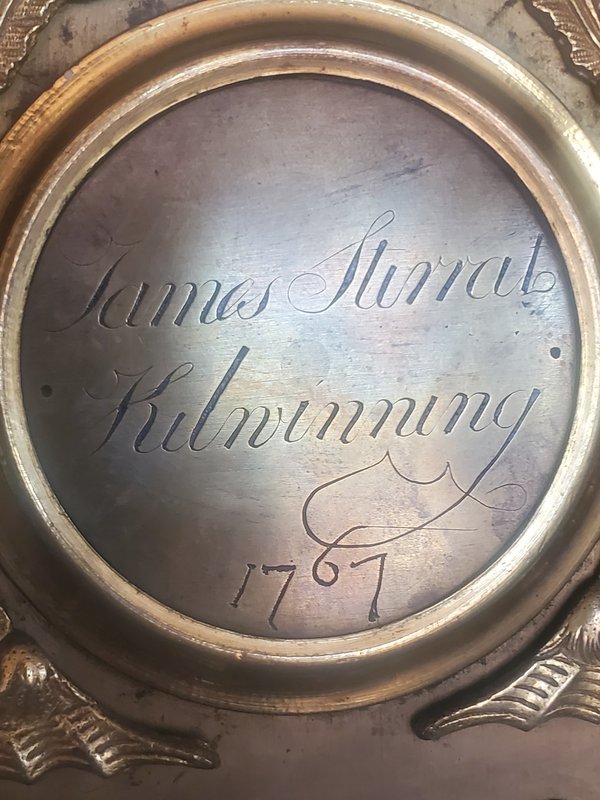

James Stirrat longcase (1767-1790); James Blair longcase and turret (c1802-1836); David Loudon (c1836-c1850); William Allan longcase (c1816-1850); Hugh Millar longcase and turret (?-1860); James Gibson longcase (1867-1882)(2); Andrew Johnstone watches (1870-1893); and William Torry longcase (c1882-c1911). Years given are dates of trading in Kilwinning.

What makes this so significant for Kilwinning’s history is the fact that while much is known of the local large-scale industry (mining, brickmaking, the ironworks), clockmaking was a hitherto unknown and undocumented industry and trade, taking place at street level. It produced a seemingly extraordinary number of clockmakers for such a small town (population 1,934 in 1820). All of this information, plus the three Kilwinning turret clocks, was published by Kilwinning Heritage as Time Piece (3) in 2019.

Following publication, we have been contacted by several people from Scotland, England, and as far away as Vancouver, Canada, and Nevada, USA, all of whom, miraculously, own Kilwinning-made longcase clocks. We would be delighted to know if there are any other Kilwinning-made clocks and watches out there. If you have one in your possession, or know of others, then please contact Kilwinning Heritage at kh2011@hotmail.co.uk. We look forward to hearing from you!

References

- Whyte, Donald (2005). Clockmakers and Watchmakers of Scotland, Mayfield Books, Ashbourne, Derbyshire

- James Gibson closing shop and William Torry taking over, Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald, 15 July 1882. www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000962/18820715/025/0001. Accessed 7 August 2019

- Upfield, Heather (2019). Time Piece: a history of James Blair and the Clocks, Clock & Watchmakers of Kilwinning 1719-2019, Kilwinning Heritage, Kilwinning www.kilwinningheritage.org.uk

Photography

Abbey Tower and James Blair turret clock: Heather Upfield

All other photographs: Current clock owners. Reproduced with kind permission

A prize-winning project 2021

This post was written by Iolanda Clopotel

My name is Iolanda Clopotel, and I have recently completed my degree in Horology studied at BCU in the School of Jewellery.

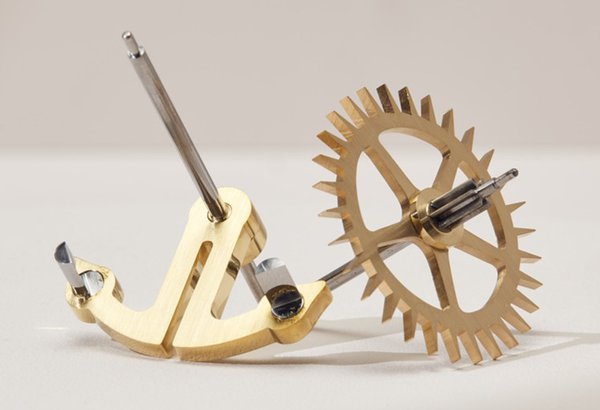

Our last and major task within the course was designing and manufacturing, from stock, a clock of our own design. This project allowed us to explore and put in practice the knowledge and skills learned in the previous years, and I have chosen to make a clock inspired by the French drum movements, featuring a Brocot escapement.

Learning more about the design of this escapement was a wonderful experience, and I am happy to have succeeded in making a working escapement by the end of the course, both in reality and in the virtual environment.

I was lucky enough to achieve the highest scoring marks in my year group and I would like to thank LVMH Watches and Jewellery for the wonderful prize in the form of a beautiful chronograph that I will wear with pride from now on, as a reminder of my own achievements.

I would also like to thank the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers for their award which will be very useful in completing future and on-going projects.

I feel grateful for the people and companies that support and reward new horologists that are just entering the field and help in keeping the passion for always improving the craft skills of precise timekeeping.

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

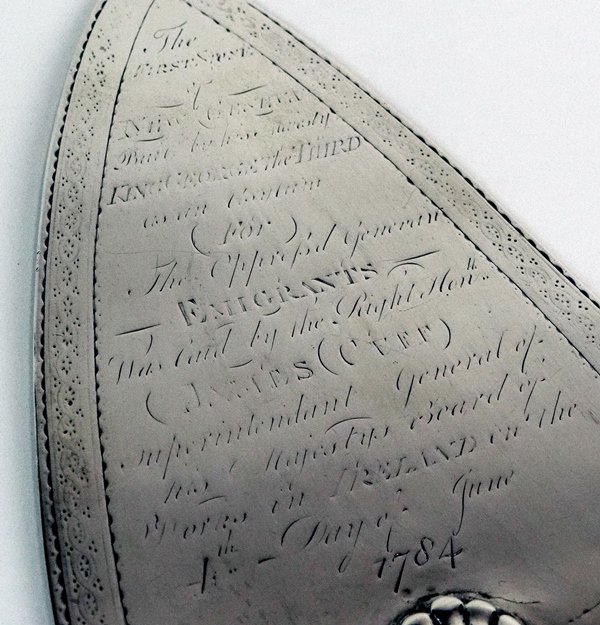

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

A musical romp in an antique clock shop

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

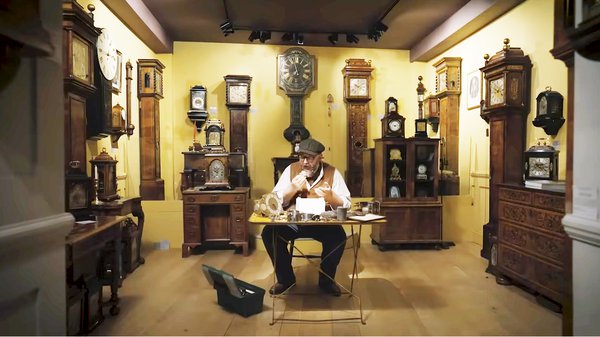

Howard Walwyn deals in fine antique clocks in Kensington Church Street, London. While his shop was closed for normal business due to the Covid crisis, he allowed it to be used for a remarkable musical entertainment: a filming of Maurice Ravel’s comical opera L’Heure Espagnole.

First performed in 1911, the opera is set in a clockmaker's shop in eighteenth-century Toledo. The title can be translated literally as ‘The Spanish Hour’, but the word heure more importantly means ‘time’ – ‘Spanish Time’, with the connotation ‘How They Keep Time in Spain’.

It is the story of a clockmaker and his wife, who hopes to have some private pleasure in the hour her husband is out winding the municipal clocks. However, the presence of a muleteer (here modernized as a UPS courier) who came in to have his watch repaired throws a spanner in the works.

It is a delightful romp – a farce – with two would-be lovers hiding inside the cases of long-case clocks (the pendulums do not appear to have been in the way!) and both ending up being persuaded to buy a clock after the clockmaker has returned.

For more information and a synopsis of the action, see here.

The opera is sung in original French with English subtitles. It is a small affair by opera standards: just 50 minutes long, and only five characters, no choir. It was pre-recorded in the Wigmore Hall in London, and the (excellent) singers acted out their roles in the shop. In this small-budget production the orchestra is replaced by a piano, but that doesn't detract from the pleasure of seeing and hearing it performed with such gusto.

The opera has been staged regularly since 1911, and will undoubtedly have many more performances. But it will never be repeated with such an abundance of authentic ‘props’ as can be seen in this entertaining video recorded in Howard Walwyn’s shop.

Stories of an everyday timepiece

This post was written by Andrew Hyatt

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. One of the things that interest me in horology as a student are the stories that timepieces can tell. Whilst the world changing events of John Harrison’s H1 through to H5 or the exciting life of Larcum Kendall’s K2 do make for fascinating reading, I am talking about the story every timepiece that I hope to end up servicing will tell me.

This story is not necessarily the emotional attachment that the owner undoubtedly has to the item. That can be interesting, but in taking apart one of my first clocks I found what I consider to be a much more interesting story.

The clock shown below is a mass produced 2 train clock with a rack striking mechanism. I picked it up because I loved the art-deco style case and the unusually shaped dial.

It is clear that several other people also did as when I took the movement apart my initial observations found a couple of things, the first is that at some point the pendulum suspension spring has been replaced. Both the rod and the back cock have been bent to accommodate a new plastic topped spring shown below.

This made me a little worried about the rest of the mechanism with what appeared to be a quick fix to get the clock running again, but as I continued I found evidence of what may have been a more caring hand. The back cock also shows evidence of the escapement/crutch arbor pivot hole having been re-bushed with the finish almost invisible on the acting face. One of the click springs has also partially sheared, but then its been re-blued.

This tells the story of one or more people that got this clock running again and I am excited to add my name to that list, hopefully in a less noticeable way, as this clock continues its story.

Elizabeth Tower from construction to conservation

This post was written by Jane Desborough

On a cold, dark evening recently my spirits were lifted when I had the pleasure of listening to an online lecture on the conservation work that has been undertaken on the Elizabeth Tower at Westminster.

Presented by tour guide, Catherine, who is clearly very experienced in talking about the Tower, the clock and the bells, it was a really engaging and accessible gallop through the history and overview of the recent conservation works.

For fans of horology, there were no big surprises – most people know the story about the cracked bells and the key players ( Edmund Beckett Denison, Sir George Airy, Edward John Dent and Frederick Dent) involved in the design and making of the clock – but a couple of points stood out for me.

The first was the discovery that when the clock was finished in 1854, it had to wait for the rest of the tower to be complete before it could begin its public service – this was five years later in 1859.

The idea of a paused instrument – one that’s designed to move continuously – made me think that there must have been a lot of work needed to store it safely, maintain it in good condition and to set it going five years after its production. It was interesting to hear that those five years provided some time for experimentation with the escapement.

Another fascinating aspect of the talk was centred on the lamps required to light the dials at night. Recent conservation work has replaced all of the lamps with LEDs.

As a more efficient lamp, the LED will obviously be a good energy-saver. The change makes sense, but I couldn’t help being pleasantly surprised that the same changes being made at a small, household scale are also being made on a larger scale with our public buildings.

For me this talk was great because you can think you know a clock or a building, but there’s always something new to discover!

Opening my first clock

This post was written by Alexandra Verejanu

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. In the context of the lockdown I got pretty behind in my studies as we couldn’t go into the workshop. As I knew it would be helpful to see and touch a mechanism, I decided to buy some cheap old clocks. The clock I have 'played' with brought some interesting questions to my attention.

Firstly, I couldn’t take it out of the case, probably because it didn't seem to have been made to be serviced. I might have stumbled upon one of those old American clocks which were made to look fashionable in the house, but after a few years were discarded as uneconomical to repair. .

I looked closely and it was obvious someone has taken it out of its glued case using some aggressive methods, like bending the bell rod and cutting holes in the case. After two hours of struggling to carefully remove the mechanism from the case, I bent the bell rod and took it out.

Then, I examined the mechanism which was very oily. I knew excessive lubrication can do more harm than good, but I didn’t expect to see damage with the naked eye.

In the future I intend to change the damaged pieces, hopefully with some I will produce in the school workshop.

I decided not to take apart the mechanism just yet, as it was useful as a comparative item to the clocks I was presented with during online courses.

Considering this timepiece is not in its best shape, I might try to do some case work during the summer. I will not be able to fix the cuttings, but I’ll give it a good clean and maybe turn the case into an easy to open one.

This clock was very helpful during lockdown and helped me understand the mechanics of a clock. It truly helped me connect and mesh information from various sources which I was not able to understand.

Special thanks to my teacher Mathew Porton, for taking his time to answer all my questions and making sure I will be safe when I disassemble the mechanism and work on it.

The universe on our bench

This post was written by Tabea Rude

My colleague Amélie Bezárd and I had the chance to take a very close look at a so-called ‘Chronoglobium’ invented and built by Mathias Zibermayr in the first half of the 19th century in Brno (today’s Czech Republic) and Graz (Austria).

His invention, a terrestrial globe driven by a gear train including small models of the Sun and Moon within a static glass celestial globe, was intended as a teaching device to demonstrate the movements of the heavenly bodies.

Zibermayr built at least 18 of these machines, which enjoyed great popularity not just at the time, but also much later when this particular model entered the Vienna Clock Museum in 1951. Almost immediately, it appeared in the Vienna newspapers and on the museum catalogue cover page.

The machine can either be operated using a hand crank to show the movements as a time-lapse, or by a spring-driven clock movement, which also shows the time of day and day of the week.

Within the glass sphere, the shadow-hoop with ecliptic stands vertically, screwed into the back of the supporting Atlas figure. The outer hoop is fixed and shows the day of the month indication. The inner ecliptic is a gear wheel that is firmly attached to the models of Sun and Moon.

These models are attached on long arms on the rear side of the Chronoglobium. The model Sun is firmly attached on the ecliptic with a fan-like grid indicating the direction of Sun rays onto Earth.

The model Moon is moved by way of a mechanism including two wheels and two lever arms up and down to demonstrate the elliptical movement of the Moon in relation to the Earth. The models of Moon and Sun perform a whole rotation around the terrestrial globe once a ‘year’, indicated by the moving ecliptic.

A bad time in Znojmo

This post was written by James Nye

In my January 2021 London Lecture on Johann Antel (1866–1930), the Czech/German clockmaker (available to AHS members here), I condensed much, and stories were omitted, like this one–a disastrous episode.

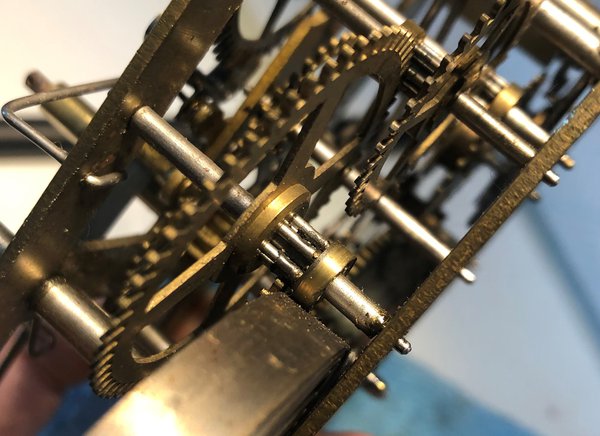

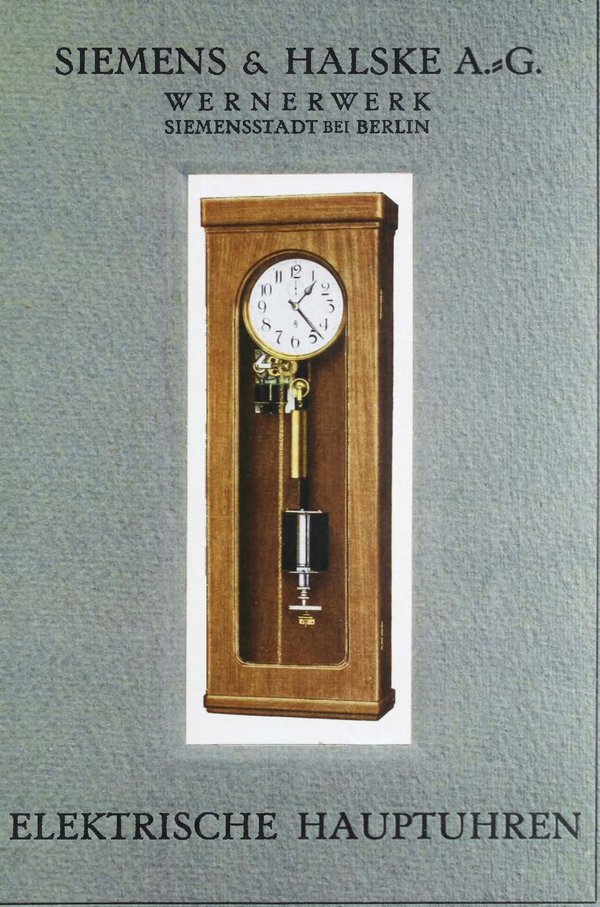

In 1930, the Znojmo authorities sought quotations for a clock for the bus-stop in Divišovo Square. Antel himself died that July, but his firm won the tender, offering a four-sided rooftop subsidiary clock, driven by a minute-impulse transmitter clock. Antel would source it from Siemens and Halske of Berlin, or its Prague subsidiary Elektrotechna.

Installation started in February 1931. In lifting the clock housing onto the bus-stop roof, the ladder slipped and both technician and clock fell to the pavement. Six weeks were lost in repairs. It was finally installed 24 March 1931. But regular attendance by the technicians over the next month suggests all was not right from the beginning.

Antel’s widow Ludmilla issued proceedings to secure payment, but matters dragged into 1932. The legal papers are actually a wonderful source of information on this catastrophic installation. The original drawings showed dials with numerals, but Antel’s firm delivered a clock with four plain dials, claiming they looked more ‘modern’.

No! said the town, we want numbers!

They also wanted a thicker gauge of glass, as the night-time illumination revealed too much of the motion-works, and the lamps were so bright the hands were invisible. A hand went missing, perhaps the fault of the technician who upgraded the glass.

In July 1933, the local paper Nas Týden reported all four dials showed a different time. A satirical piece followed in Ochrana in October, urging civic pride in a clock that showed different times on different dials, like the astronomical clock at Olomouc.

The gods never favoured the clock, and it was probably replaced in around 1938. As with an ill-fated earlier installation at the law-courts, Antel never had much luck in Znojmo.

Put down your pens: the Oxford Examinations School clocks

This post was written by Johan ten Hoeve

Located on the High Street, in the heart of Oxford, the Oxford Examinations School was built between 1876 and 1882 and made the reputation of its architect, Thomas Jackson, who incorporated materials from old buildings to construct the school. Among them, Christopher Wren’s pulpit from the Divinity School forms the Examiners throne in the North School, and many now regard the building to be Jackson’s masterpiece.

In 1883 Charles Shepherd (Jr) installed a master clock and slave system with 19 slaves. This was replaced with an expanded Gents master system, with 28 slave dials, in 1959. The current dials, which are some 30 inches across, are replacement dials, having possibly been installed along with the Gents system.

Most of the original wooden housings of the slave clocks are still fitted with the old Shepherd terminals which connected the slave clock to the system. This is the only remaining evidence that there was once was a Shepherd clock system. However, the original Shepherd master and a slave clock are still around, and can now be found in the reserve collection of the History of Science Museum, Oxford.

The slave unit is described thus: “Slave unit to the Shepherd electric master clock (78037), the mechanism closely resembling that of the master. The slave unit receives the impulse every two seconds and moves the hands of the dial. The unit has two hands but no dial. Mounted on wooden board, with unfitted Perspex cover”.

The Gents slave system still operates in the Examinations School even though Gents ceased the clock side of their business in 1999 and terminated the contract. The 28 slave dials are divided up into three sub circuits; one C73 and two C74 relay units, with a power supply, trickle charger and battery back-up.

At present, the whole system, (master and all slave clocks) is undergoing a major overhaul and service.