The AHS Blog

The popularity of horological tattoos

This post was written by Anna-Rose Kirk

Clocks and watches are the most tattooed image at the moment according to Vice magazine, and tattoo artists are sick of tattooing them.

'Clocks. Clocks, pocket watches and more clocks . Mostly on guys in their mid 20s. There must be hundreds, at the very least, being done in the UK every week. Lots of tattooists have stopped putting them in their portfolios because they’re so fed up with them' (Craig Hicks).

Time symbols have always been popular in art as reminders of the passing of life and the inevitability of death.

Hour glass tattoos have been a simple depiction of this for many years, and there has been a long tradition of symbolism within prison tattoos depicting clock and watches with no hands. However, the more recent need to capture time has sparked a trend of more complicated depictions and designs within larger tattoos often surrounded by banners, flowers, and owls.

Speaking to those that have the clock or watch tattoos, it is apparent that the most common reason was the idea of symbolising a date and time, a child’s birth for example, and was a way of avoiding text and numbers which have become a common tattoo choice.

Others wanted them as reminders that time is precious and had them tattooed in prominent places as a constant reminder to live their lives meaningfully.

One person I spoke to simply had a deep appreciation for horology and the way that watches worked after coming across them in his job in a jeweller’s and from his friends in the industry. Because of this, the time on the watch does not have a significant meaning, but it was important to him that the detail and the way it looked was right.

Celebrities and easy access to images and discussions play a part in tattoo trends but simply more people are getting tattooed meaning particular images seem to get used more often.

I wanted to get to the bottom of whether clocks and watches were seen as something mysterious with no concept of the inside workings, however, although a lot of the general public, especially the younger generation, does not understand the exact mechanics of a pocket watch, they have a tangible feel which in contrast to today’s sleek, minimal, computerised technology can feel a lot more real. They feel as if the have a history and a story; linked to memories tradition and ritual.

I wonder if a rise in nostalgia and a romanticism for craftsmanship and the handmade has brought about the rise of this style being used in tattooing and movements like Steam Punk.

It is perhaps a fight against excessive consumption of the 21st century and the dehumanisation of manufacturing and the idea that traditional skills may be lost. It seems to be that horology is being worn as a symbol of authenticity and a preservation of history in a vain attempt to show that this generation care.

Bomb found outside AHS meeting focused on bomb scares

This post was written by David Rooney

The strangest thing happened last Thursday. To be honest, I thought it was a put-up job and so did many of the people with me. I thought James Nye had arranged it; everyone else thought I had.

It was the first AHS London Lecture of 2017. We’re in a new venue this year. Following the success of last year’s programme things were getting a bit tight at Cannon Place and we needed a bigger room with space to grow, so thanks to an introduction from our Council Member James Stratton, head of the clocks department at Bonhams, we have been able to move to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) on Parliament Square, overlooking the Houses of Parliament and the Great Clock of Westminster.

I was the lecturer for our first meeting at RICS. I’ve been thinking a lot over the years about the political symbolism of time: how it stands for other things besides when to catch the train. So my talk last Thursday was about standard time and violent protest in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth.

Specifically, I was focusing on two bomb attacks: one on the Royal Observatory Greenwich in 1894 by an anarchist and one on the Royal Observatory Edinburgh in 1913 by suffragettes.

Both attacks, I argued, were symbolic strikes against scientifically defined standard time but both were very real, resulting in loss of life at Greenwich and significant damage at Edinburgh. They were attacks on the establishment – an establishment centred at Westminster just a few paces from where I was speaking.

My talk finished bang on time at 7.15pm and I was getting ready to answer questions when the house manager came in and whispered a message to James, who was chairing the evening.

I assumed it was a minor problem with the catering laid on thanks to the generosity of sponsor Jonny Flower – maybe the prosecco wasn’t chilled enough or the hors d’oeuvres were running late. But I was wrong.

We’d all seen the flashing blue lights through the frosted windows of the lecture room, but they are not an unusual sight in Westminster and we thought little of it. Perhaps a car had been pulled over, or a tourist had taken a tumble. Certainly nothing out of the ordinary.

Then James interrupted proceedings to tell the audience that much of the area outside, including bridges and tube stations, was being sealed off by the police.

We really thought it was a put-up job when he told us that a bomb had been found by Westminster Bridge. It was not a false alarm. It was a real bomb – from the Second World War. It had been found by a dredger in the River Thames.

The police call to the Royal Navy bomb disposal squad went in at exactly 7.15pm – the moment I stopped speaking.

Don’t worry. Nobody was hurt in the incident and the bomb was safely detonated early the following morning at Tilbury. The March lecture is about the gold workers and enamellers of Geneva and we’re not expecting any bother.

A gala for Lisa

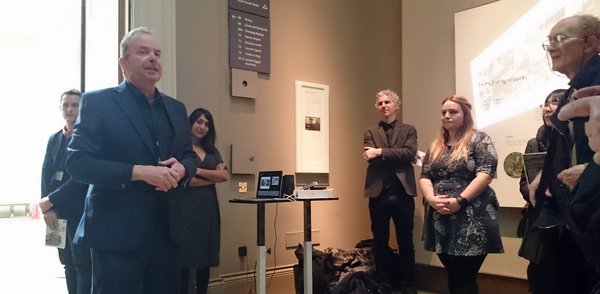

This post was written by James Nye

Tuesday 25 October 2016: to the Victoria and Albert Museum for a fabulous evening to celebrate the life of our late President, Lisa Jardine FRSA, in the company of her husband John Hare, members of the family, and a distinguished array of academics, curators, writers, and lots of friends. It was a year to the date since Lisa’s death.

Lisa believed in lectures that were also a bit of a party. We gathered in the Whiteley Silver Gallery to the sound of a jazz trio, and moved to the astonishing Gorvy Lecture Theatre, where we were greeted by Bill Sherman of the V&A, a colleague of Lisa’s over many years.

He introduced Amanda Vickery, who spoke movingly of her long and close association with Lisa, before introducing the remarkable Deborah Harkness, prize-winning historian and now best-selling author, noted for the All Souls fictional trilogy.

She spoke on ‘Fiction in the Archives’, explaining how a parallel career in fiction has enriched her historical work, following an approach she believes Lisa enshrined – not so much ‘outreach’ – more the invitation to everyone to come and spend time inside the ivory tower.

The spine-tingling thrill of archival discovery is accessible and communicable to all—and truth can be more remarkable than fiction. Setting action in her scholarly backyard—sixteenth century Blackfriars—Deborah told us that ‘Fiction at last allows me to tell people what I really think happened, rather than what I can prove.’

It was a tour de force—resolving to the notion that literature can work to promote empathy, a characteristic in short supply in conflicts at all levels, globally. Deborah’s tribute linked this to Lisa, who championed diversity, bringing together so many people, across so many communities.

John rounded off proceedings by announcing the launch of a new initiative with the Royal Society—the Lisa Jardine Research Awards—essentially funding to encourage the study of the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment, an initiative for which significant backing has already been secured. A very fitting tribute indeed.

The evening wound up with a reception in the galleries housing the Ionides collection, to the sound of more jazz. Our hosts were generous, but were probably mindful of Lisa’s mantra—‘never knowingly undercater’—it was a magical event.

‘A clock which has gone by itself for 2 years’

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In the State Library of New South Wales is a manuscript journal of a trip to Holland undertaken in 1773 by the naturalist Joseph Banks (1743-1820), who from 1778 until his death was to be the President of the Royal Society. His journal can be read on-line here.

Most of his journal, as expected, is related to natural history, but in Amsterdam he visited an unnamed clockmaker who showed him ‘a clock which has gone by itself for 2 years’.

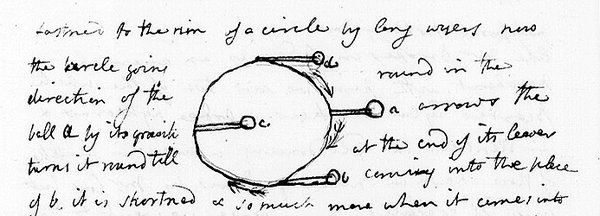

From his description, complete with a sketch, it is clear that he struggled to make sense of what he had seen:

'From hence we went to a clockmaker Mr [name not entered] who has invented a clock which has gone by itself for 2 years & is therefore called not injustly a perpetual motion whether the principle was fallacious I could not discover but it was or appeared to be 4 balls / fastened to the rim of a circle by long wyers [wires] the circle going round in the direction of the arrows the ball a by its gravity turns it round till at the end of its leaver [??] coming into the place of b it is shortened and so much more when it comes into the place of c the balls c & d at the same time becoming longer & in their turns forcing it round whether however a [illegible word] wheel made upon this construction would ever go once round I very much doubt if not there must either be fallacy or some method of applying the principle which I did not understand which is likely as the machine was rather complicated' (pages 51 and 52 – CY 3011/73 and 74).

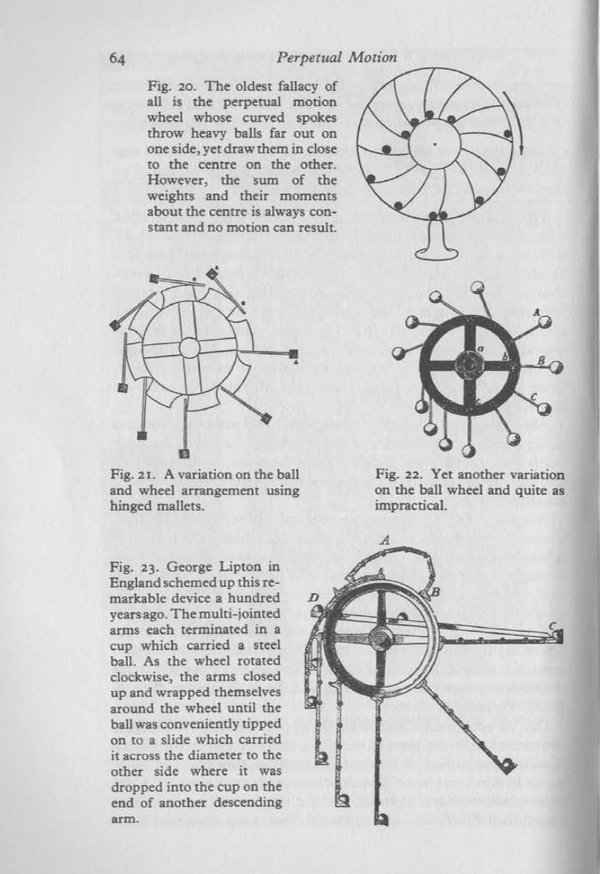

The concept of perpetual motion, and the idea that one can make a machine that can do work indefinitely without an energy source, has been exercising many minds over the centuries, but the development of modern theories of thermodynamics has shown that they are impossible.

In his book Perpetual Motion: the History of an Obsession, Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume has illustrated several devices that look rather similar to the clock that Banks had seen. We must conclude that the unnamed Amsterdam clockmaker was one in a long line of deluded ‘inventors’.

A new addition to the galleries at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

The extraordinarily accurate ‘Burgess Clock B’ was recently installed in the Royal Observatory’s Time and Longitude Gallery where it will be on display for the next three years.

The following filmed interview introduces the work of Martin Burgess and the project behind this remarkable timekeeper.

First shown at the Harrison Decoded conference, held at the National Maritime Museum in April, 2015.

Further information on Clock B can be found here.

A supplementary (late) meeting report (from 1957)

This post was written by James Nye

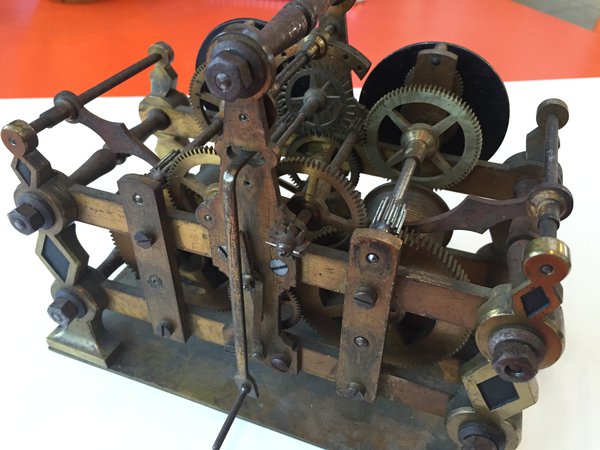

Petrol rationing ceased in May 1957, but the legendary Colonel Quill, DSO, had long planned the AHS September visit with a view to everyone needing to use public transport, staying local in London.

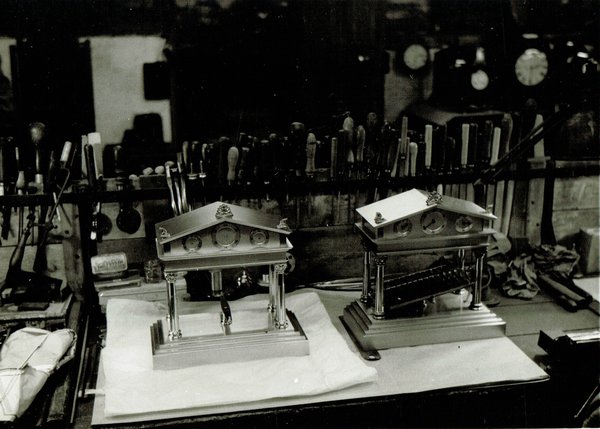

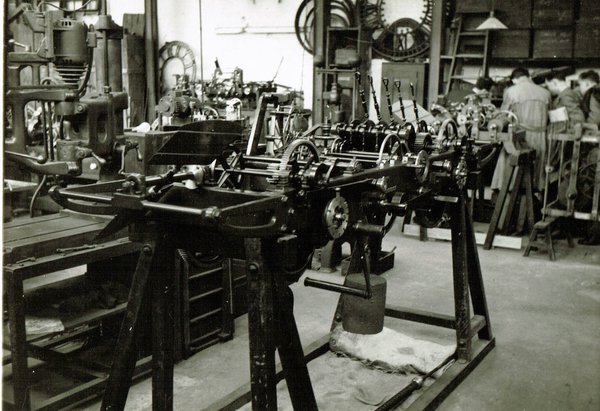

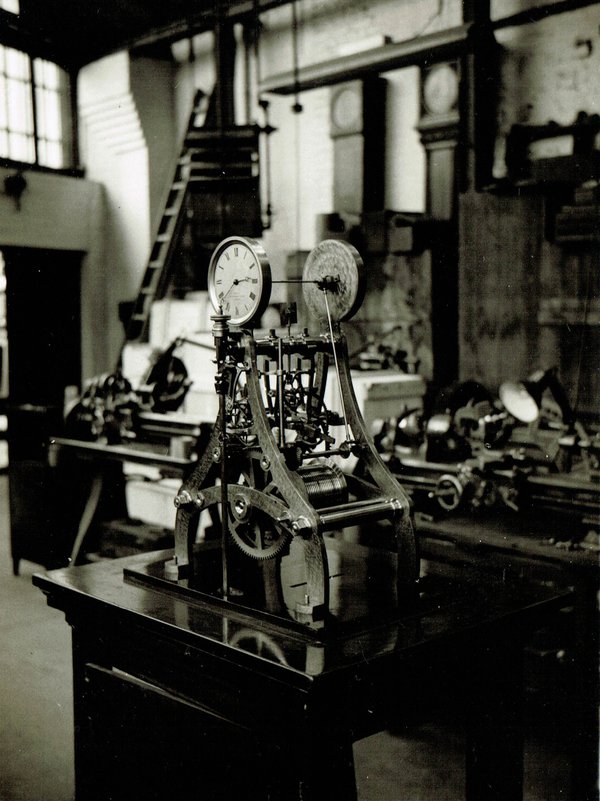

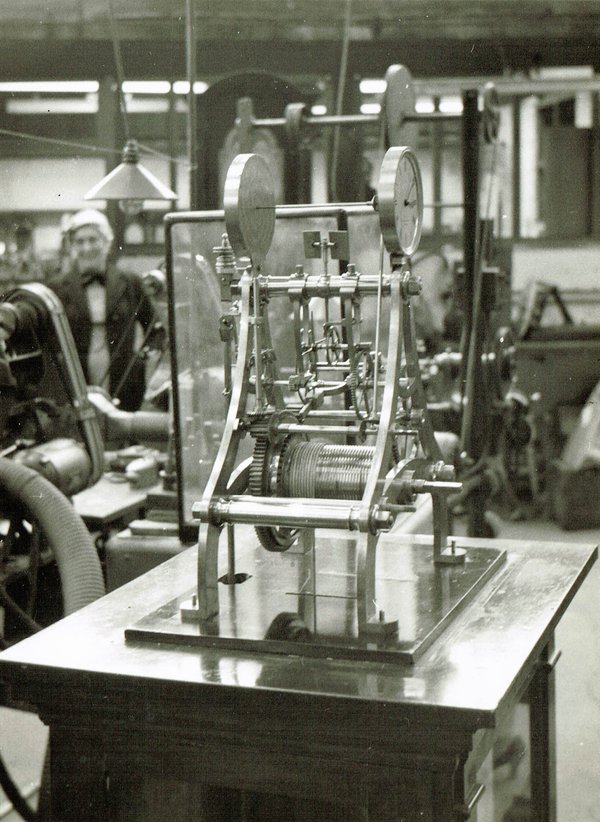

About forty members and friends descended on the workshops of E. J. Dent & Co in Lambeth, but the meeting report (AH Dec 1957, p. 95) was text only.

On the day, pictures were taken by our distinguished early member Bob Miles, but not being used these found their way into an envelope, to disappear in our archive, until I had a look inside, nearly sixty years later, a few days ago. I thought it was high time they had some exposure.

Daniel Buckney (great grandson of E.J Dent) and AHS founder member Charles Williams, both of Dent, showed everyone round.

The objects on view ranged from a striking wrought iron cage clock by Edmund Howard of Chelsea (1761), through to modern editions of the Congreve rolling ball clock, a design which continued to be made for several more decades.

In the case of the Howard, substantial information has come to light in recent days, and I will try to resolve this into an article for the journal as soon as possible.

Being Dents’ workshop, there were turret clocks aplenty, of course, including examples not only from Dent, but Benson, of a wide variety of shapes and sizes.

An unusual and quite large 1939 Dent quarter-striking gravity escapement clock sported intriguing fans mounted either end, and within the frame, pivoted horizontally at right-angles to the train.

It had a most unusual gravity escapement, with the escape wheel formed in the shape of a hexagram. It later found its way to the Science Museum, where it still resides.

A wonderful exhibition model turret/skeleton clock was on display, which later found its way to the Rockford Time Museum, and thence to a fabulous private collection. A British Pathé film taken in the workshops only a short time later features many of the same clocks.

The joys opening old envelopes can bring!

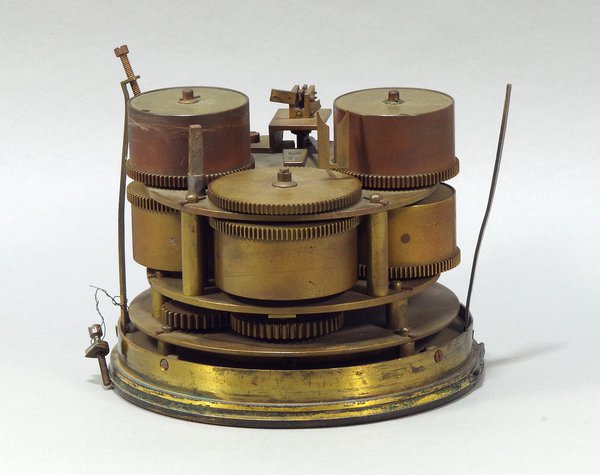

The compound pendulum in a precision timekeeper?!

This post was written by Tabea Rude

Popular and well known examples of compound pendulums in horology are found in French novelty clocks. They can be camouflaged as an innocent sailor, as in the mantel clock on display at the Royal Observatory Greenwich...

...but mostly compound pendulums are regarded as a nightmare when it comes to precision.

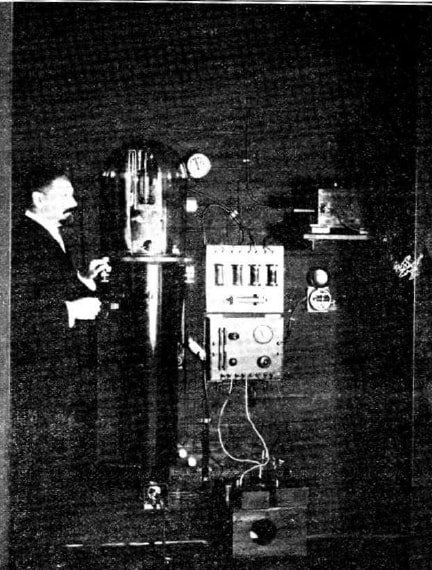

This was not always the case, as I found out in the conservation and research into an electromechanical double pendulum clock, patented by M. Pierre Sellier in 1909.

Sellier’s patent clock (on display at The Clockworks) uses a compound pendulum to provide the drive to the hands, while a ‘free’ pendulum controls the electro-magnetic impulsing of the compound pendulum, by making and breaking the drive circuit.

Sellier’s invention was, like most other compound pendulums, lacking in precision, but in the early 20th century he was not alone in using a compound pendulum in the quest for precision time keeping.

In other horological circles, consideration was given to the compound pendulum as a potentially useful component.

While in 1909 the Deutsche Uhrmacherzeitung described the compound pendulum as a ‘rape of the pendulum principle’, a major article by Prof. Dr. Ing. H. Bock in 1929 in the same magazine reported on a compound pendulum as a precision break-through.

After criticising the suspension spring type used in Shortt’s free pendulum for its variable elasticity modulus, Bock introduced Dr. Max Schuler’s idea of exchanging Shortt’s free pendulum for a compound pendulum resting on a knife edge.

He claimed that Schuler would soon be able to measure all the anomalies in the Earth’s rotation and outperform the Shortt clock with ‘German toughness’.

The Schuler clock has ended up at the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum at Furtwangen, and no doubt we will hear more about in due course!

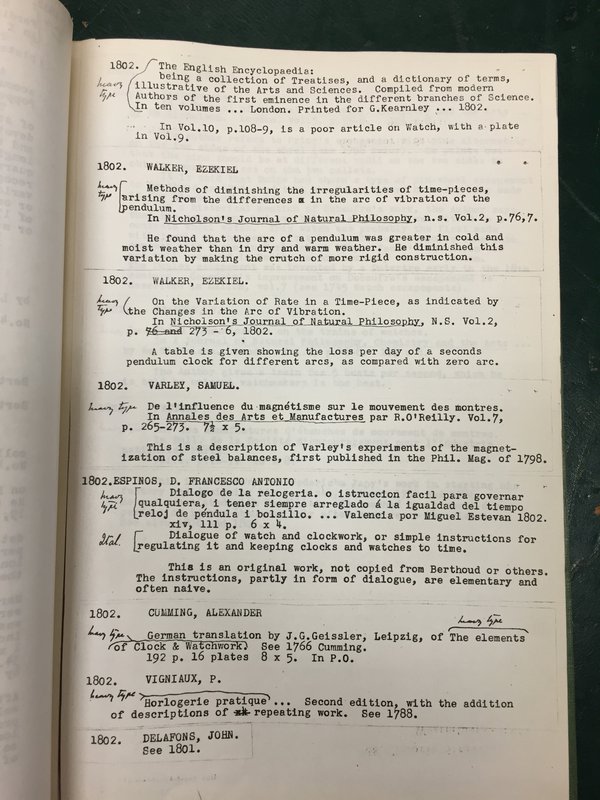

Better late than never – Baillie Bibliography Vol 2

This post was written by James Nye

Someone I know is researching the electric clock systems of Ritchie. Being a pro, I rather suspect they have run a lot of obscure sources to earth, but I’m going to make a point of drawing their attention to English Mechanic and World of Science from 1874, where I believe Ritchie published a piece on controlling clocks and time-signals by electricity.

This might come as an interesting addition to the better known 1878 piece in the Journal of the Society of Arts (vol. 26).

Another friend has a forthcoming piece on the pneumatic time distribution systems of Mayrhofer, which will appear in the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie’s next yearbook. There is just a chance he may not have come across the 1882 piece by Berly in the Journal of the Society of Arts, providing an overview of the state of the art in pneumatic horology.

How on earth do I come to know of these possibly useful references? In 1951, G.H. Baillie published an historical bibliography, covering horological literature published prior to 1800. It has been a goldmine ever since.

A second volume, covering literature published between 1800 and 1899, was drafted, but never published – until now. The AHS has arranged the copy-typing of the typescript, and a digital (searchable) version is now available to download from the members’ area of the website.

It’s a fantastic new resource for researchers. Yes, all the obvious literature is there, of course, but there are also vast numbers of obscure references which will illuminate your research.

And Baillie included the good, the bad and the ugly.

An 1889 article on watch cocks by Luthmer is described simply – ‘the illustrations are very good. The text is of little value’. Parker-Rhodes’ 1885 pamphlet on ‘Universal Reading of Time; is ‘of no value or interest’.

But Baillie is unstinting in his praise where it is merited – witness the simple observation on Poppe’s 1801 Ausführliche Geschichte der theoretisch~praktischen Uhrmacherkunst , that ‘this is by far the best history of horology that has ever been written. Hardly a statement is made without a full reference to the authority for it.’

Membership of the AHS brings you full digital access to over sixty years of Antiquarian Horology , and other amazing digitized records – such as this latest bibliography, which finally makes an appearance sixty-five years after the author’s death. It is worth investigating.

Time from the mains

This post was written by James Nye

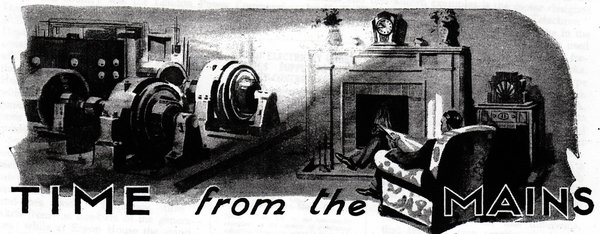

In 1931, Wireless World published a powerful pictorial depiction of timekeeping from the electric mains. Today, we check the time on our smartphones and glance at standalone battery-driven quartz clocks on walls at home and at work, and it would be easy to assume that time from the mains had been consigned to history.

But look around. On countless supermarkets, town halls, churches and other public buildings the clocks you see run from the AC mains and take their time from the frequency of the UK’s national grid.

These are synchronous motor clocks, running at a speed dictated by the grid’s frequency. To work as clocks, that frequency needs to remain very close to 50Hz. If the frequency drifts, engineers steer it back, avoiding cumulative clock error.

The UK’s Grid Code specifies that National Grid must control the frequency so that clock time remains within plus or minus 10 seconds per day. Thus while synchronous clocks might display an error of up to 10 seconds within a 24-hour period, in practice the error will daily be brought to zero by the 7.00am handover of shifts at the National Grid’s Control Centre in rural Berkshire.

On 11 June 2016, a few enthusiasts from the AHS Electrical Group were granted rare and privileged access to the Control Centre to hear at first hand from its highly experienced and knowledgeable engineers how they handle not only the management of the grid in real time but also how they predict what the load will be a few hours in the future.

Two concerns drive the never-ending work of the engineers: security of supply and efficiency.

Keeping the lights on is paramount but once that is assured, market mechanisms are used to allocate resources.

Reserve power is expensive, so cannot be contracted lightly. Unpredictable supply from renewable sources causes massive headaches. Inertia – enough mass in the form of spinning metal in the turbines connected to the grid – is vital to smooth volatile flows of power.

Grid time was seven seconds slow on our arrival and four seconds slow on our departure – a few hours later after an enlightening and highly informative tour packed with rich detail delivered with confidence from our expert guides.

That our synchronous clocks perform so well is no longer a mystery, given the phenomenal technical and intellectual effort deployed 24/7 to keep the lights on – and to keep those clocks on time.

Mannheim, April 2016

This post was written by James Nye

Friday 15 April 2016 – to Mannheim Seckenheim for the 17th annual electric clock fair, organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven, the chairman of the DGC’s Electrical Horology Group.

This has long become an essential part of the social calendar of Euro-electro-horology, bringing as usual visitors from the UK, Switzerland, France, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany.

The fair coincided with a remarkable exhibition mounted by Hans Baumann, showing part of his extensive collection of electric watches, showcased in his two-volume publication from 2013.

Several hundred watches were on show, from electro-magnetically maintained balances, through tuning fork examples, onward to early quartz.

The international crew enjoyed themselves with two excellent evening meals, and a visit to the Carl Benz museum in Ladenburg.

In between times, a lot of objects changed hands – on the principle that much collecting involves storing objects for a number of years, and then passing the job of storage to the next collector.

As always, there were several items, not on sale but on show, which became the subject of repeated interrogation and discussion.

One of these was a fabulous time printer from Löbner of Berlin, of exactly the type used at the Berlin Olympics, together with a Ulysse Nardin pocket chronometer, to record race times (see Schraven’s article on Short Time Measurement in Antiquarian Horology , Dec 2015).

Another crowd-puller was a stunning but miniature ‘turret clock’ from Hörz of Ulm, the only example known, and referenced in a single catalogue (c.1905). This involves two weight-driven trains – one going and the other, in place of striking, to drive a polwender each minute (the device which sends alternate polarity pulses to subsidiary clocks).

This extraordinary survivor of an early 20th century master clock saw groups gathered for extended periods of time, counting teeth and attempting to rationalise the apparently problematic logic of its design.

A fabulous, multi-cultural weekend of fun, fine food and great friends.

Plans for an important clock

This post was written by James Nye

St Luke’s church (c.1825) in West Norwood, London, has an extremely fine clock (c.1827) by Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy, costing some 3 per cent of the budget for the church and the equivalent of several hundred thousands of modern pounds.

It is probably the first flat-bed turret clock in England, embodying ideas developed by Vulliamy on recent Continental travels.

Vulliamy’s clocks were substantially more expensive than those of his competitors, but he boldly claimed they would outperform and outlive cheaper alternatives. While it may not presently be working, a recent survey of St Luke’s revealed a very high quality clock, still in remarkable order.

Clock towers are deeply inhospitable environments, cycling in temperature between plus 40 degrees C and falling below zero – with humidity varying from low to 100 per cent over time.

The natural modern trend to move away from weekly attendance by a clock winder necessitates auto-winding, but St Luke’s system has failed.

There are further problems. Vulliamy’s slate dials were replaced with opal glazed versions in 1928, but the putty fixing of the panels has dried to a cement-like hardness, and the lack of flexibility allows for cracking of the glass, as the cast iron tracery expands and contracts.

Moisture can creep in, leading to ‘rust-jacking’. Several panels failed long ago, being replaced in wholly unsuitable plastic, offering a patchwork impression at night. Many other panels are cracked, and the eventual failure of the glazing is certain, while the clock room suffers.

The church is now launching a substantial project to repair the clock, add new auto-winding and auto-regulation, but, significantly and most expensively, also to repair all four dials with new opal glass.

This is a project of great significance to the community of West Norwood – the clock is highly visible and a symbol of local civic pride over two centuries.

Action and pressure from the local community has led to the present proposals for a project to restore the clock to function. Fortunately, a number of different members of the Society have also been offer to valuable input and assistance, and fundraising is well underway.

Fire! Fire!

This post was written by James Nye

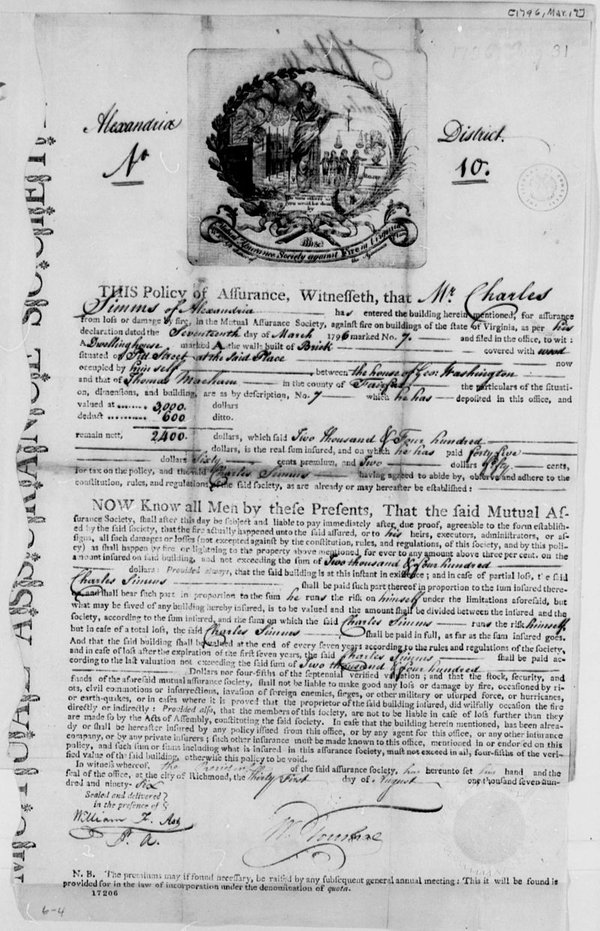

The AHS has launched a fascinating new research resource for its members – a series of searchable fire insurance records, covering the period 1710 to 1863.

Over many years, the late Roger Carrington (1948–2005) manually transcribed fire insurance records now held at the London Metropolitan Archive (LMA), and his work has been digitalized and added to the AHS web-site.

The LMA catalogue describes the holdings of a ‘substantial, if incomplete series of fire policy registers’ which survive for several insurance companies, including Sun Life (from 1710 to 1863), and Royal Exchange (from 1754 to 1759, and 1773 to 1863).

Roger focused on the policies of clockmakers and watchmakers, and related trades.

We have created downloadable and searchable pdfs. The key benefit is the digital searchability of all six thousand one hundred and twenty records involved.

What can one discover?

Well, as the catalogue notes indicate, ‘Where fire policy registers exist, they generally include the following information: policy number, name of agent/location of agency; name, status, occupation and address of policy holder; names, occupations and addresses of tenants (where relevant); location, type, nature of construction and value of property insured; premium; renewal date; and some indication of endorsements […] Sun Fire insurance policies were renewed after five years at which time a new policy was issued under a new number.’

The data are of great interest to the horological researcher for a wide variety of possible reasons.

The records can be searched for the name of a clockmaker, watchmaker or anyone involved in related trades. If the relevant name appears, the details of a policy can then be reviewed – potentially revealing new and interesting contextual material (e.g. verifying an address for a given date range, indicating prosperity or lack of it, etc.)

The records could be interrogated in a different way, for example by location, occupation or street name.

Many will find the searchable pdfs sufficient, in simply locating information to be found in the main policy transcriptions. However, some may wish to do more with the data, and to this end we have provided an index in Excel, which will allow for more sophisticated searches of the data.

This valuable resource is only available to AHS members, so do join up if you think it might be useful in your research. AHS membership is terrific value and your subscription helps support our mission to foster the study of the story of time.

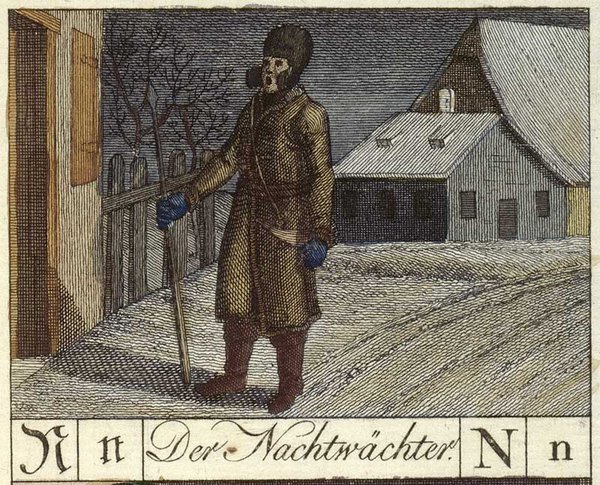

Night watchmen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Richard Wagner set his glorious opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-singers of Nuremberg) in that German city in the sixteenth century.

In the second act a night watchman sings (the English translation in the vocal score is somewhat awkward as it aims to preserve both metre and rhyme):

'Hark to what I say, good people;

strikes ten from every steeple;

put out your fire and eke your light,

that none may take harm this night.

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat zehn geschlagen;

bewahrt das Feuer und auch das Licht,

dass Niemand Schad‘ geschicht.

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

The act concludes with his re-appearance:

'Hark to what I say, good people;

eleven strikes from each steeple;

defend you from spectre and sprite;

let no power ill your souls of fright!

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat elfe geschlagen;

bewahrt euch vor Gespenster und spuck,

dass kein böser Geist eu’r Seel‘ beruck‘!

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

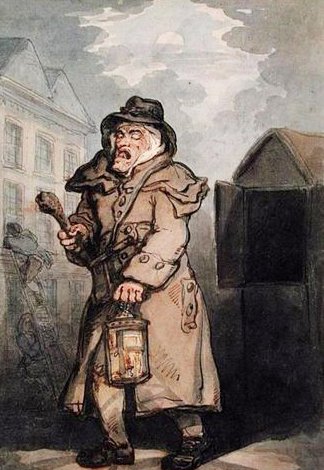

From the middle ages until late into the nineteenth century, the night watchman patrolling the streets at night, calling the time and keeping an eye out for any kind of mischief or irregularities, were a common figure in many towns and cities.

Although he set his opera in the sixteenth century, watchmen were probably still active in Nuremberg when Wagner wrote his opera in the 1860s.

One century earlier, an Englishman visiting Nuremberg recorded in his travel journal 'Every evening about nine o’clock a fellow goes up and down the streets singing, and gives notice of the time of night, and bids people put out their candles. About the same time and at three in the morning trumpets are sounded.' (Sir Philip Skippon, An Account of a Journey Made Thro’ Part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and France , 1752).

In her book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London , Judith Flanders writes that for a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock, stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time.

The patrols of the night watchmen were not an undivided pleasure.

In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Tobias Smollett has a long-suffering character say, 'I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants.'

Acknowledgment. It was Wagner’s opera that made me want to know more about these night watch men, and I found much information in this article: Philip McCouat, ‘Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night’, Journal of Art in Society (2014), www.artinsociety.com.

Clockpera at the British Museum

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

The pairing of clocks and opera has been a recurring theme in this blog (1, 2, 3) and I am now happy to report on another such coincidence.

Over recent years, members of an opera production company, Brolly Productions, have made several visits to horological study room at the British Museum (where I work).

They came to look at different kinds of clocks and understand how they work, in order to provide a solid foundation for the design of their latest production, “CLOCKS 1888: The greener”.

The lead character is a 'greener', i.e. 'an immigrant who has only recently arrived', who were common to East London in the 19th century in which the opera is set.

She is responsible for maintaining the clock that controls the workforce of the East End but she comes under pressure from her overseer to alter its running to increase production.

Also, 'of course it is an opera, so there has to be a love story' says Dominic Hingorani, Librettist & Director of Brolly Productions.

Last Friday lunchtime, in the horological gallery of the BM, an event was held to celebrate the collaboration.

The highlight of this were two songs from the production, performed by Keisha Atwell, who plays Greener. Freddie Matthews, Head of Adult Programmes of the BM, introduced the event.

Dominic then spoke about the evolution of the production. Rachana Jadav, Designer & Illustrator of Brolly Productions, spoke of the creation of the design, including the influence of the BM clocks.

Also speaking was Paul Buck, Curator of Horology of the BM, who told how the horological team embraces access to the collection and will consider even the most diverse requests. Indeed, access to the collection is available to all students, not only horologists.

Members of the AHS have the opportunity to visit the horological study room for talks from the curators and close-up viewing of objects. These group visits are organized by the AHS’s regional sections.

CLOCKS 1888: The greener is playing at CAST Doncaster, Fri 15th April to Sat 16th April 2016 and at the Hackney Empire, Wed 20th April to Fri 22nd April 2016.

Wristwatch Group meeting, 14th January: conservation and restoration

This post was written by Mat Craddock

In the gas-fired warmth of the Royal Arcade, WWG members heard Justin Koullapis (our gracious host, The Watch Club), Adam Phillips (casemaker and restorer), Greg Dowling (WWG member and watch collector) and Oliver Cooke (Curator, Horological Collections at the British Museum) discuss originality in watches.

Oli’s curatorial view of conservation was, perhaps, the most extreme: once an item enters a collection, the aim is to put it into stasis, free from the damaging effects of winding or lubrication.

From a collector’s point of view, Greg said that the possibility of wearing and using a watch might lead him to seek out to the most appropriate way to restore the piece to working order.

Adam agreed, and seemed largely happy to undertake work under the direction of his customers, taking the view that sensitive restoration and repair can extend the useful life of a watch.

Justin’s thoughts on the subject were from two, contrasting, points of view: as a non-practising watchmaker and as a watch dealer. He said that great value is placed on entirely original objects, many of which have been hidden away for many year. However, his fascination with how objects were made often caused him to place more value on the skills of the watchmaker, rather than the watch itself.

Questions were taken from the audience, and covered topics such as dealer versus collector (the panel was split on the definition of a collection); the dangers of old radium (the British Museum has their luminous watches stored in steel-lined rooms that are externally force vented); and even the purpose of collecting watches.

In response to the last question, Mr Dowling quoted from the late Dr George Daniels: there’s nothing more attractive than a good watch. It’s historic, intellectual, technical, aesthetic, amusing, useful.

A fitting end to an interesting evening.

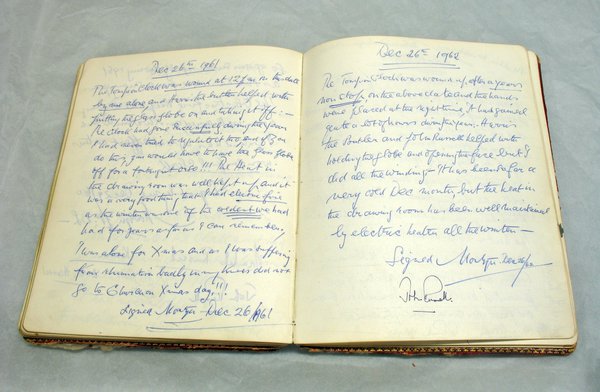

The annual winding of the Mostyn Tompion

This post was written by James Nye

28 January 2016. To the British Museum, at the delightful invitation of the horology curators to take part in a little-known and wonderful ceremony – the just-once-a-year winding of the glorious Mostyn Tompion.

The Deputy Director, Jonathan Williams, offered a warm welcome, amply elaborated by Paul Buck, senior horological curator, who walked us around the origins and detail of this extraordinary object.

It runs for a whole year on one wind, striking every hour of that year (56,940 blows). The clock case, a confection of ebony veneer, silver and gilded brass, is rich in symbolism, covered in the heraldry and armorial paraphernalia of England and Scotland, richly intertwined – an interesting hint to the politicians who only wind each other up on such matters.

Made for King William III by perhaps our most celebrated maker – Thomas Tompion ( Westminster Abbey-buried, no less) – the clock descended on the royal death through various titled families before settling with the family of the early Lords Mostyn, finally landing in Great Russell Street in 1982.

From c.1793, the Lords Mostyn held a small party to mark the annual winding of the clock, with each winder entering their name in a book. This tradition has been kept firmly alive at the British Museum.

The old family record was open for us to see, turned to the page for 26 December 1961, when Lord Mostyn recorded being on his own for Christmas, and winding the clock, which had ‘gone successfully during the year’.

Amusingly his idea of being on his own did not allow for the presence of the butler, who helped replace the dome over the clock.

These were memorable times – Mostyn, much troubled by rheumatism, also recorded ‘The heat in the drawing room was well kept up, and it was a very good thing that I had electric fire as the winter was of the coldest we had had for years’.

Winter, spring, summer and fall continue to unfold, watched over from Gallery 39 by a remarkable clock, which draws breath just once in each cycle of seasons.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ Time Machine: perpetual calendar or not?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

I am fascinated by gimmicks used by past watch manufacturers to make their products stand out in a crowded marketplace and this post is the first in a short series on some attention seeking watches that have piqued my interest.

This post takes a look the Wittnauer ‘2000’, a quirky automatic wrist watch from the 1970s.

It is a snazzy-looking chunk of a watch and is impressively big at 46mm across the case and crown; the dial does not disappoint with its day, date and complex-looking calendar information around two apertures at twelve and six o’clock.

It was advertised in the early 1970s as a time machine with perpetual calendar, which is technically correct but arguably a little misleading.

The perpetual calendar is a celebrated complication prized by collectors of high-end wrist and pocket watches.

The intricate mechanism required to keep the calendar in step with the short months and leap years demands multiple precisely made components, is only found on the best watches and, unsurprisingly, its presence in a watch hikes the value substantially.

Stephen McDonnell’s recent innovative perpetual calendar design. Uploaded to Youtube by Quill and Pad.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ has a perpetual calendar, which does conform to the same definition.

The date display is a standard type, which must be manually advanced at the end of a short month. It is more normal for the calendar to be set using the crown, but why do that when you can have an extra button on the outside of the case? Instead of keeping the date in sync, it uses tables and a revolving scale to reckon the day of the week for a given date.

The mechanics of the design are very simple, the revolving disc has a contrate gear on its reverse, which is driven by a pinion attached to a second crown.

The years and days of the week are printed on the revolving disc and, as can be seen in the image, aligning the year with the month on the lower table (at six o’clock), places each day of the week above one of seven columns (at twelve o’clock) that contain the relevant days of the month.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ perpetual calendar employed an old and simple technology to allude to luxury. For a modest price it had bags of 70s style and, as with any self-respecting time machine, had buttons aplenty!

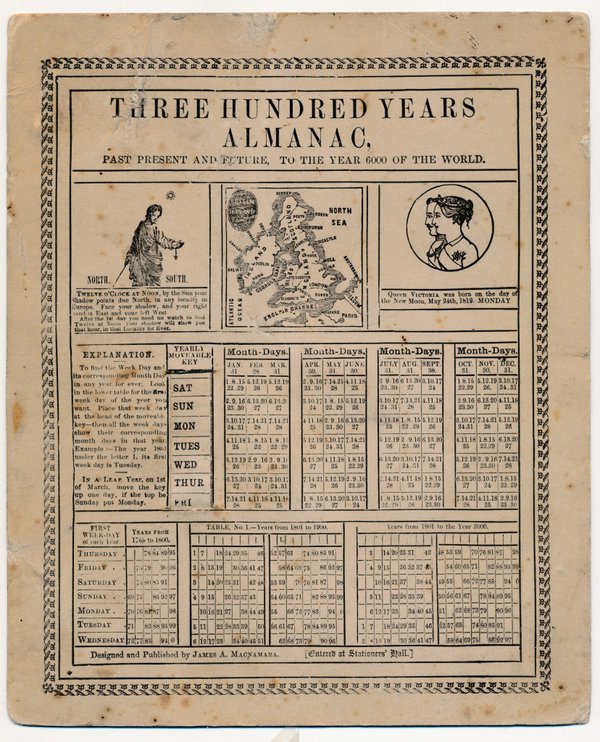

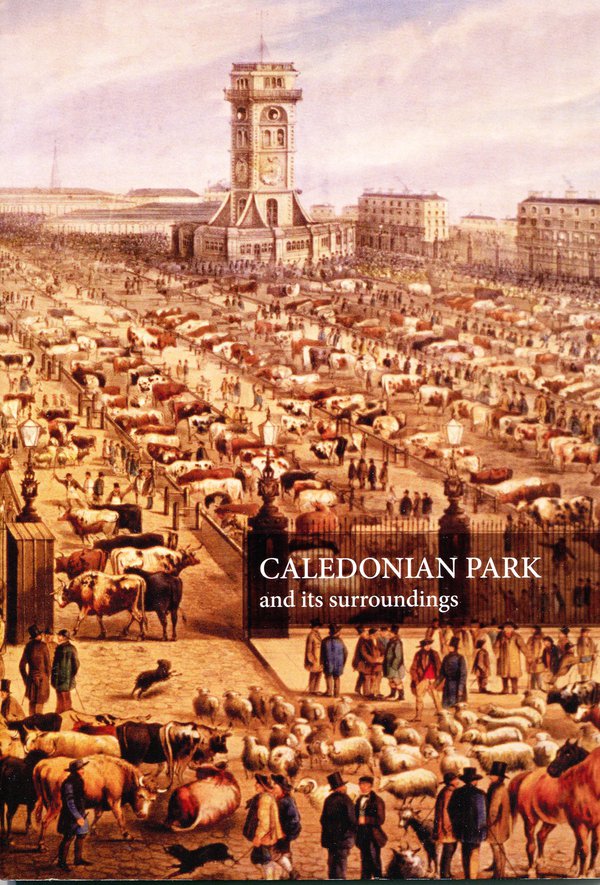

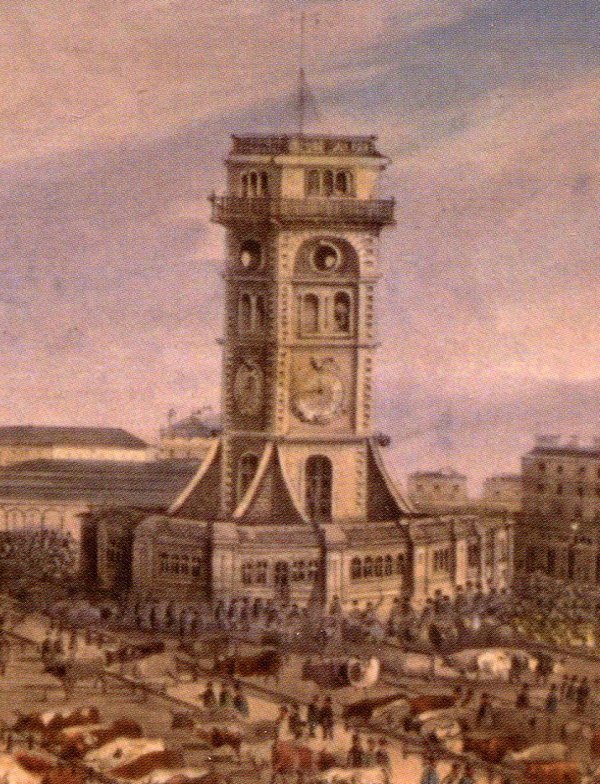

Winding the Caledonian Park turret clock

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In Caledonian Park, in the London Borough of Islington, stands a distinctive 45 meter clock tower with four dials that can be seen from far away.

It was erected in the 1850s to serve as the command centre of the newly laid out Metropolitan Cattle Market, which had been created to replace the old more centrally located Smithfield Market. The tower is a Grade II listed building.

You can see the clock movement in this short videoclip:

Turret clock expert Chris McKay has recently published a facsimile reproduction of A List of Church, Turret and Musical Clocks. Manufactured by John Moore & Sons. 38 & 39, Clerkenwell Close, London, dated 1877.

For the year 1854 we find: ‘Islington, London Four 10-ft. 6-in. dials, chiming, for the Cattle Market.’

The chimes are no longer in operation, from what I understand at the insistence of nearby residents. But the clock is still running and showing the correct time.

During an open day last summer I had a chance to get into the tower, and to see the clock and enjoy the view from the balcony.

The organizers were looking to extend their group of volunteers for the weekly winding of the clock. I signed up and am on the rota now, so I regularly climb first a cast iron spiral staircase and then a series of steep ladders to get to the movement and pull up the heavy weight.

It’s a good physical exercise and a welcome hands-on experience for someone whose involvement with horology is normally limited to sitting at a desk putting together the quarterly journal of the AHS.

The Caledonian Park Friends Group have published a booklet with much information on the history of the market, which for a while also functioned as a flea market.

The cover shows the market in full swing, but the artist has made a bad job of representing the tower. If the dials were really as low as where he painted them, climbing up to wind the clock would be a lot easier!

Donation to the British Museum

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

I write with a foot in two allied camps: as a member of the AHS and a Curator of Horology at the British Museum.

In October last year the AHS Council generously donated sixteen interesting clocks, watches and horological tools to the BM collections. The items had in fact been at the BM since 1973, having been deposited on long-term loan when the AHS left its former London HQ.

This conversion to a donation consolidates that loan and upholds one of the core objectives of the AHS which is the support of public collections.

Let us look at three of the items.

Firstly, a lantern clock with centre verge pendulum by Johannes Kent of Congleton, Cheshire, late 17th century.

Lantern clocks with centre pendulum sometimes had 'angel wing' extensions to the side doors to accommodate the arc of pendulum. This clock does not have these, but the side doors (which seem to be later) do not interfere with the action of the pendulum.

Unusually for this time, the clock does not have Huygens’s endless winding system, but has a separate drive for each train.

Next, an interesting year-going movement. This was probably housed in a slate or marble case, perhaps something like this.

The inscription on the dial is somewhat rubbed and not wholly legible, but it seems to be signed for Edward Watson of King Street, Cheapside, London (working 1815-63) who would have been the retailer for the clock.

The movement is stamped to show that it was made by Achille Brocot of Paris. Brocot invented this type of long duration movement in the mid-19th century, employing multiple mainsprings in going barrels to drive the clock.

The system has great advantages over using a single large mainspring to achieve a long duration. Smaller springs are easier to make and much easier to remove for maintenance. Also, if one of the five springs were to break it would cause far less damage to the clock than a recently-wound single spring with a year’s worth of driving energy being unleashed.

… and finally, an unusual and incredibly useful screwdriver. It has five slot heads at different orientations enabling access to those awkward screws, such as between the plates of a movement.

Right, I’m off to attend to a newly-installed longcase clock which has stopped – an in-situ adjustment of the back cock should do it..!

As with all items in the collections of the British Museum, these items are kept to be made accessible to all members of the public. An appointment to study them can be made by contacting the horological team at horological@britishmuseum.org or by telephone (020 7323 8395).

How did Arnold get to the Clockmakers’ Museum?

This post was written by David Rooney

On 23 October, the Clockmakers’ Museum opened at the Science Museum. The new gallery is a treasure-trove of horological history, home to so many wonderful items it’s hard to know where to look next.

Tucked away in one showcase is a modest-looking pocket watch that would be easy to miss, yet tells a story close to my heart—that of Ruth Belville, whose biography I wrote in 2008.

The watch was originally the property of John Belville, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, who used it between 1836 and his death twenty years later to carry accurate Greenwich Time round a network of subscribers across London.

When John died in 1856, the watch was passed to Maria, his wife, who continued carrying it round London until 1892, when she retired.

She then passed it to her daughter, Ruth, who named it ‘Arnold’ after its maker, John Arnold. Ruth carried the time to town with Arnold until 1940, when she retired, aged 86.

But it was not the end of the line for Arnold. Ruth had always wanted it to have a good home.

‘When it retires from business … I think the dear old thing ought to be put in the British Museum’, she told the Evening News in 1908. In 1921, Ruth changed her mind, stating that she ‘should wish the Royal Observatory to have the first offer of purchasing my chronometer’.

Yet neither received Arnold.

In 1941, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers granted Ruth a pension which gave her crucial financial security in her retirement.

Ruth repaid its generosity in January 1943, when she wrote to the Company offering her watch for its museum when the time came. The Company accepted, noting that ‘by doing so her name would be perpetuated for all time’.

Eight months later, Ruth died with Arnold by her bedside. The watch was duly transferred to the Company’s collection and ended up on display at Guildhall.

Now I needn’t go to Guildhall to see Arnold—delightful though my visits there always were—but instead I can pop into the magnificent new gallery at the Science Museum during my lunch break.

I hope you’ll have a chance to see it too.