The AHS Blog

Elizabeth Tower from construction to conservation

This post was written by Jane Desborough

On a cold, dark evening recently my spirits were lifted when I had the pleasure of listening to an online lecture on the conservation work that has been undertaken on the Elizabeth Tower at Westminster.

Presented by tour guide, Catherine, who is clearly very experienced in talking about the Tower, the clock and the bells, it was a really engaging and accessible gallop through the history and overview of the recent conservation works.

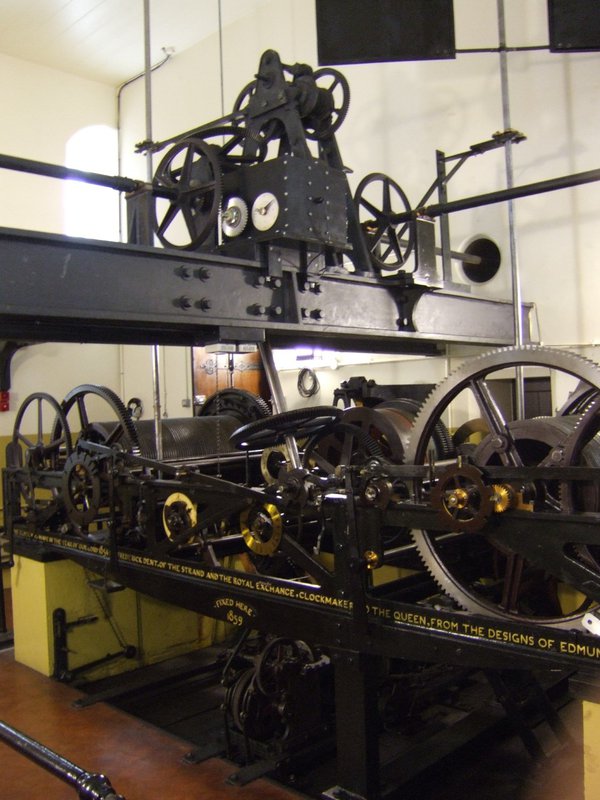

For fans of horology, there were no big surprises – most people know the story about the cracked bells and the key players ( Edmund Beckett Denison, Sir George Airy, Edward John Dent and Frederick Dent) involved in the design and making of the clock – but a couple of points stood out for me.

The first was the discovery that when the clock was finished in 1854, it had to wait for the rest of the tower to be complete before it could begin its public service – this was five years later in 1859.

The idea of a paused instrument – one that’s designed to move continuously – made me think that there must have been a lot of work needed to store it safely, maintain it in good condition and to set it going five years after its production. It was interesting to hear that those five years provided some time for experimentation with the escapement.

Another fascinating aspect of the talk was centred on the lamps required to light the dials at night. Recent conservation work has replaced all of the lamps with LEDs.

As a more efficient lamp, the LED will obviously be a good energy-saver. The change makes sense, but I couldn’t help being pleasantly surprised that the same changes being made at a small, household scale are also being made on a larger scale with our public buildings.

For me this talk was great because you can think you know a clock or a building, but there’s always something new to discover!

Opening my first clock

This post was written by Alexandra Verejanu

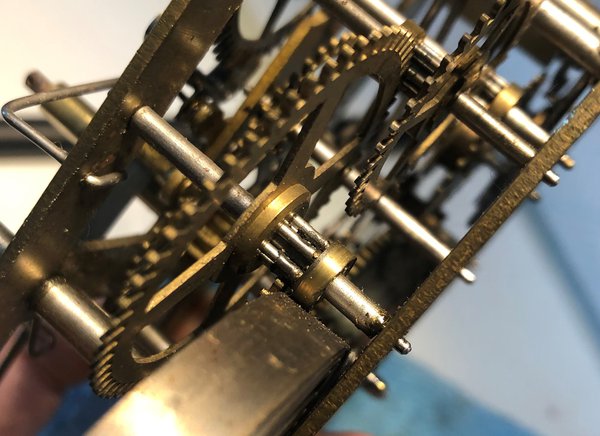

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. In the context of the lockdown I got pretty behind in my studies as we couldn’t go into the workshop. As I knew it would be helpful to see and touch a mechanism, I decided to buy some cheap old clocks. The clock I have 'played' with brought some interesting questions to my attention.

Firstly, I couldn’t take it out of the case, probably because it didn't seem to have been made to be serviced. I might have stumbled upon one of those old American clocks which were made to look fashionable in the house, but after a few years were discarded as uneconomical to repair. .

I looked closely and it was obvious someone has taken it out of its glued case using some aggressive methods, like bending the bell rod and cutting holes in the case. After two hours of struggling to carefully remove the mechanism from the case, I bent the bell rod and took it out.

Then, I examined the mechanism which was very oily. I knew excessive lubrication can do more harm than good, but I didn’t expect to see damage with the naked eye.

In the future I intend to change the damaged pieces, hopefully with some I will produce in the school workshop.

I decided not to take apart the mechanism just yet, as it was useful as a comparative item to the clocks I was presented with during online courses.

Considering this timepiece is not in its best shape, I might try to do some case work during the summer. I will not be able to fix the cuttings, but I’ll give it a good clean and maybe turn the case into an easy to open one.

This clock was very helpful during lockdown and helped me understand the mechanics of a clock. It truly helped me connect and mesh information from various sources which I was not able to understand.

Special thanks to my teacher Mathew Porton, for taking his time to answer all my questions and making sure I will be safe when I disassemble the mechanism and work on it.

The universe on our bench

This post was written by Tabea Rude

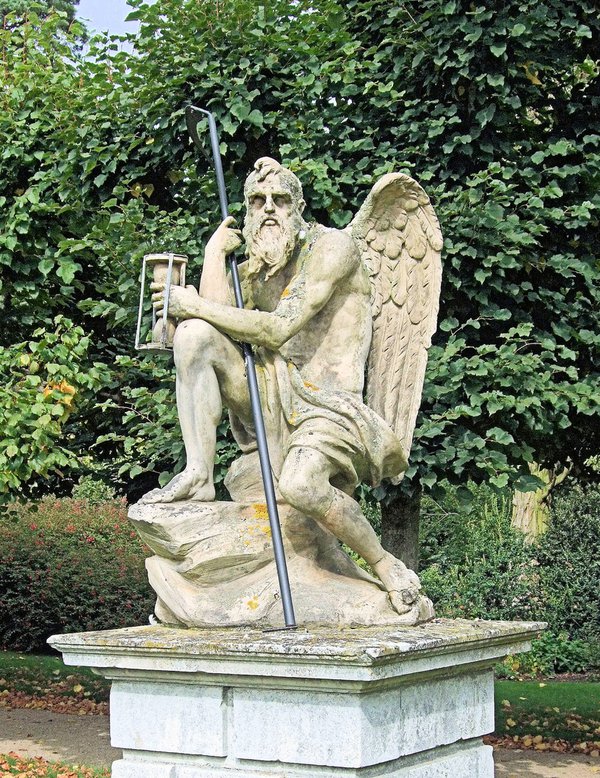

My colleague Amélie Bezárd and I had the chance to take a very close look at a so-called ‘Chronoglobium’ invented and built by Mathias Zibermayr in the first half of the 19th century in Brno (today’s Czech Republic) and Graz (Austria).

His invention, a terrestrial globe driven by a gear train including small models of the Sun and Moon within a static glass celestial globe, was intended as a teaching device to demonstrate the movements of the heavenly bodies.

Zibermayr built at least 18 of these machines, which enjoyed great popularity not just at the time, but also much later when this particular model entered the Vienna Clock Museum in 1951. Almost immediately, it appeared in the Vienna newspapers and on the museum catalogue cover page.

The machine can either be operated using a hand crank to show the movements as a time-lapse, or by a spring-driven clock movement, which also shows the time of day and day of the week.

Within the glass sphere, the shadow-hoop with ecliptic stands vertically, screwed into the back of the supporting Atlas figure. The outer hoop is fixed and shows the day of the month indication. The inner ecliptic is a gear wheel that is firmly attached to the models of Sun and Moon.

These models are attached on long arms on the rear side of the Chronoglobium. The model Sun is firmly attached on the ecliptic with a fan-like grid indicating the direction of Sun rays onto Earth.

The model Moon is moved by way of a mechanism including two wheels and two lever arms up and down to demonstrate the elliptical movement of the Moon in relation to the Earth. The models of Moon and Sun perform a whole rotation around the terrestrial globe once a ‘year’, indicated by the moving ecliptic.

A few examples of contemporary typography in watchmaking

This post was written by Lee Yuen-Rapati

The evolution of typography in horology has come a long way from the dominance of Roman numerals and the round hand script. While the mid-twentieth century remains a potent library of inspiration for today’s watch brands, other watchmakers look forward in creating their timepieces.

These contemporary watches can appear non-traditional or even avant garde, with typography to match. However a closer look reveals that even the newest typography on watches still has connections to the past.

The use of bold and blocky sans-serif numerals is a common trend in many contemporary watches that try to eschew a sense of antiquity, at least on the surface. A prime example is the collection from Urwerk who have consistently used a bold and angular style of numerals since their inception in the late 1990s. The ultra high-end pieces from Greubel Forsey also feature rather rectangular numerals which both match the aesthetics of their main collection, but provide an interesting juxtaposition in their Hand Made 1 as well as the Naissance d’une Montre (1) watch, both of which highlight more traditional watchmaking techniques.

The use of bold and blocky numerals is more of an evolution for a company like Rolex who have adopted them across their recent collection, notably on the Explorer and GMT-Master II models. While none of the examples above are likely to be mistaken for antique pieces, similar rectangular or blocky numerals were popular in the art deco era and into the mid-twentieth century. Even if the watch is new, the link to the past is sometimes quite prominently promoted as with the unabashedly contemporary (and divisive) Code 11.59 collection which features numerals adapted from a 1940s Audemars Piguet minute repeater.

Some contemporary watches pull from outside the horological world to define themselves. Hermès as well as the young company anOrdain each sought out type designers to create new and identifiable typography. Hermès got its modernist numerals from the studio of Philippe Apeloig for its Slim d’Hermès line while anOrdain’s typographer Imogen Ayres created numerals inspired by survey maps. Neither brands’ numerals are completely new, but their lack of typographic precedence in the watch world make them both stand out.

Other brands use more traditional numerals but change the material in order to place their watches firmly in the twenty-first century. H. Moser & Cie’s Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue uses applique numerals that are inspired by 1920s pilot’s watches. The appliques are made from the luminous material Globolight rather than metal. In a similar fashion, the refounded British brand Vertex uses moulded Super-LumiNova numerals in lieu of traditionally painted or printed numerals on their military-inspired watches. Kari Voutilainen offers the option for brightly coloured arabic appliques on his watches which bring a youthful presence to his more classically designed dials. Dimensionality has long been a useful styling tool for watchmakers, and the inclusion of new materials has produced some very refreshing results.

The examples above represent a few different typographic paths for the contemporary watchmaker to follow. While these watches and their typography may appear to share very little with antiquity, there are always links to trace back, they are simply being shown from a new angle.

Photo credits:

- Baruch Coutts @budgecoutts (Urwerk, UR-UR111C)

- Greubel Forsey (Hand Made 1)

- Atom Moore @atommoore (Rolex, GMT Master II)

- Audemars Piguet (Code 11.59 Selfwinding White)

- Baruch Coutts (Hermès, Slim D’Hermès Titane)

- AnOrdain (Model 2 Blue Fumé)

- H Moser & Cie (Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue)

- Vertex (M100)

- Atom Moore (Voutilainen, TP1 OW2019)

A bad time in Znojmo

This post was written by James Nye

In my January 2021 London Lecture on Johann Antel (1866–1930), the Czech/German clockmaker (available to AHS members here), I condensed much, and stories were omitted, like this one–a disastrous episode.

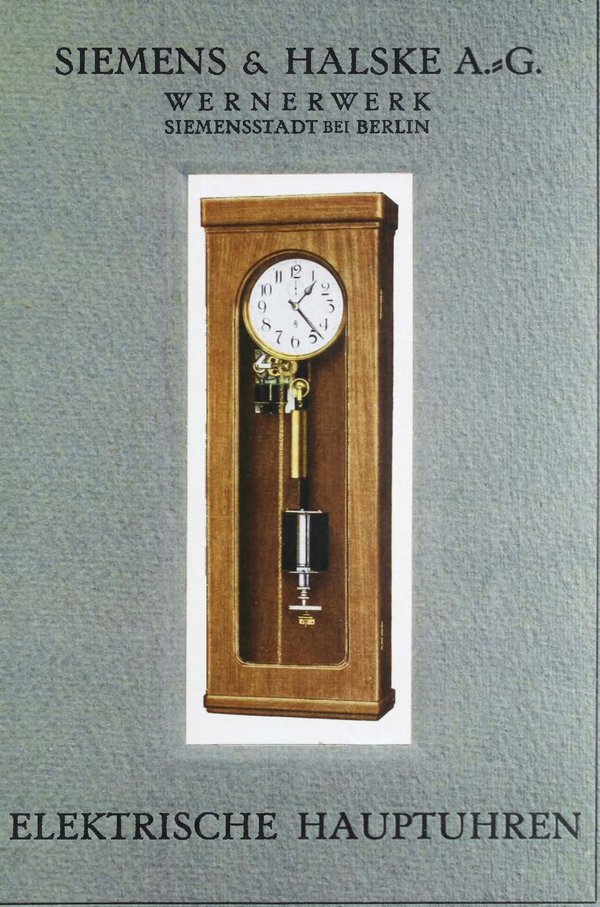

In 1930, the Znojmo authorities sought quotations for a clock for the bus-stop in Divišovo Square. Antel himself died that July, but his firm won the tender, offering a four-sided rooftop subsidiary clock, driven by a minute-impulse transmitter clock. Antel would source it from Siemens and Halske of Berlin, or its Prague subsidiary Elektrotechna.

Installation started in February 1931. In lifting the clock housing onto the bus-stop roof, the ladder slipped and both technician and clock fell to the pavement. Six weeks were lost in repairs. It was finally installed 24 March 1931. But regular attendance by the technicians over the next month suggests all was not right from the beginning.

Antel’s widow Ludmilla issued proceedings to secure payment, but matters dragged into 1932. The legal papers are actually a wonderful source of information on this catastrophic installation. The original drawings showed dials with numerals, but Antel’s firm delivered a clock with four plain dials, claiming they looked more ‘modern’.

No! said the town, we want numbers!

They also wanted a thicker gauge of glass, as the night-time illumination revealed too much of the motion-works, and the lamps were so bright the hands were invisible. A hand went missing, perhaps the fault of the technician who upgraded the glass.

In July 1933, the local paper Nas Týden reported all four dials showed a different time. A satirical piece followed in Ochrana in October, urging civic pride in a clock that showed different times on different dials, like the astronomical clock at Olomouc.

The gods never favoured the clock, and it was probably replaced in around 1938. As with an ill-fated earlier installation at the law-courts, Antel never had much luck in Znojmo.

The engineer’s chronometer: William Wilson and the Adler

This post was written by Allan C. Purcell

Last Summer I bought on eBay this fusee chain driven watch with detent escapement, dia 50mm, hallmarked Chester 1858, signed on the movement ‘William Benton of Liverpool, No. 5115’, and on the dial ‘Chronometer watch by William Benton 148 Park Road Liverpool’.

In the description of the watch, the seller had written ‘Opening below to reveal a highly decorated dust cover “Stephenson’s Rocket, Steam Train”, and clean fully working highly decorated “Steam Paddle Ship”.’

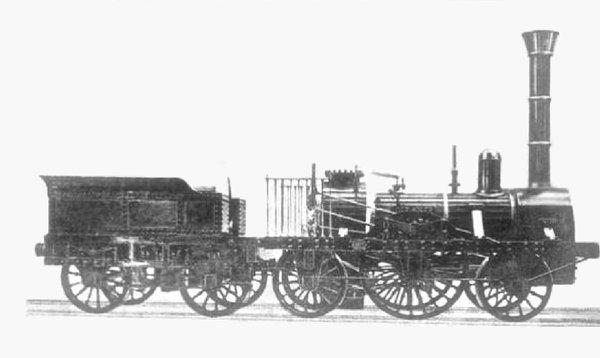

What the seller failed to point out is that the watch is inscribed on the dustcap ‘WILLM WILSON / LIVERPOOL / AD 1859’. It is my belief that this was the English engineer William Wilson (1809-1862), and that the locomotive illustrated on the watch is not the Rocket but the Adler (German for: Eagle), the first locomotive successfully used commercially for the rail transport of passengers and goods in Germany.

In 1835, George & Robert Stephenson in Newcastle were contracted by the Bavarian Ludwig railway company to build an engine for their first railway to run from Nuremberg to Furth. They sent the new locomotive packed in boxes, and their engineer William Wilson was contracted to rebuild it there. The train was a huge success and Wilson stayed with the Ludwig railway company for another twenty-five years, driving the train in all weathers. In 1859, William was covered in glory by the German railway company. In 1862 he died and was buried in Nuremberg, where his descendants are still living.

While Stephenson’s Rocket has only four wheels, the Adler had six wheels (wheel arrangement 2-2-2 in Whyte notation or 1A1 in UIC classification). The engraving on the watch shows a locomotive with six wheels. The image of the ship engraved on the watch may refer to the steamboat Hercules which in September 1835 had been used to transport the boxes containing the locomotive from Rotterdam on the Rhine to Cologne.

When in September last year I went to Nuremberg for the Ward Francillon Time Symposium, I arranged an appointment with Stefan Ebenfeld, the director of artefacts and library at the Museum of the German Railway (Deutsche Bahn Museum) in Nuremberg. It turned out that the museum had no personal artefacts of Wilson’s, and we agreed that the museum would buy the watch from me for the price I paid for it.

For anyone interested in more details, there are entries on William Wilson and the Adler on Wikipedia.

Put down your pens: the Oxford Examinations School clocks

This post was written by Johan ten Hoeve

Located on the High Street, in the heart of Oxford, the Oxford Examinations School was built between 1876 and 1882 and made the reputation of its architect, Thomas Jackson, who incorporated materials from old buildings to construct the school. Among them, Christopher Wren’s pulpit from the Divinity School forms the Examiners throne in the North School, and many now regard the building to be Jackson’s masterpiece.

In 1883 Charles Shepherd (Jr) installed a master clock and slave system with 19 slaves. This was replaced with an expanded Gents master system, with 28 slave dials, in 1959. The current dials, which are some 30 inches across, are replacement dials, having possibly been installed along with the Gents system.

Most of the original wooden housings of the slave clocks are still fitted with the old Shepherd terminals which connected the slave clock to the system. This is the only remaining evidence that there was once was a Shepherd clock system. However, the original Shepherd master and a slave clock are still around, and can now be found in the reserve collection of the History of Science Museum, Oxford.

The slave unit is described thus: “Slave unit to the Shepherd electric master clock (78037), the mechanism closely resembling that of the master. The slave unit receives the impulse every two seconds and moves the hands of the dial. The unit has two hands but no dial. Mounted on wooden board, with unfitted Perspex cover”.

The Gents slave system still operates in the Examinations School even though Gents ceased the clock side of their business in 1999 and terminated the contract. The 28 slave dials are divided up into three sub circuits; one C73 and two C74 relay units, with a power supply, trickle charger and battery back-up.

At present, the whole system, (master and all slave clocks) is undergoing a major overhaul and service.

Was there high-quality, wholesale, clock movement manufacture in seventeenth-century London?

This post was written by James Nye

There is a fascinating article in the latest edition of Antiquarian Horology, just starting to arrive through people’s letterboxes, setting out a remarkable research question which cries out for some crowdsourcing of data—hence this blog post. For those who don’t receive a physical journal, the editor has conveniently made it the sample article for this quarter. You can download it here.

Put simply, it is suggested a range of prominent makers (or perhaps retailers) bought in largely finished movements from a single source, and arranged for their casing/signature/final finishing.

This is clearly a very well-understood practice in the watch world from a relatively early date, and was certainly common practice in the clock world later on. For example, Thwaites produced movements for a wide range of other clockmakers and clockmaking firms, and on a large scale.

The question remains, how early did this standard practice emerge, and is there sufficient physical evidence to allow us to draw firm conclusions?

The key element is that Jon’s piece is a call to arms! More data is needed. And it is not difficult to look for it. This is a massively worthwhile project to support, and whatever the outcome, if you can supply data you can play a part in improving our understanding of clockmaking practice in London in the period 1660–1720. Please do get involved!

The second edition of 'Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping'

This post was written by Charles Ormrod

Robert Miles’s landmark work, Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping , sold out a few years after its original publication in 2011. Since then, copies of this highly sought-after book have been selling for several times the original cover price of £50.

The AHS is therefore delighted to announce that a long-awaited second edition is now available, made to the same standards as the first, hard-backed and thread-bound, at a new low price of just £25 plus postage.

As a humble labourer in the vineyard of the second edition, assisting James Nye with administrative work but certainly not with Synchronome expertise, I’ve had a first-class opportunity to learn about the pitfalls of editing, proof-reading, and the finer points of book production.

The possibility of a second edition was mooted some years ago, and revisions to the first edition had been contributed by Bob Miles himself, Derek Bird, Norman Heckenberg, Arthur Mitchell and others.

One of my first jobs was to combine these various sets of revisions into one document, eventually about eight A4 pages long, for presentation to the designer of the first edition, Phil Carr. Phil very generously made no charge for all the work of entering revisions into a new version of the original book’s electronic file.

Double-checking the changes and exploring disagreements between contributors led to many absorbing hours searching for clarification. I now know far more than I did about the history of sonar and the extent to which Second-World-War sonar sound-pulses fell within an audible range (which depended on whether the listener was a fit young sailor or an old sea dog).

I also learned about the Doppler effect on the sound of swinging tower-clock bells, the problems of reproducing the appearance of pre-war electrical flex, alternative cabinet-making methods applied to Synchronome cases, and the best method of setting up the suspension of a Synchronome pendulum.

I must admit I hadn’t quite realised that high-quality hard-backed books, such as the first and second editions of Synchronome, really are still made by sewing groups of double pages together with thread. A machine does the sewing of course, but the principle is broadly the same as with the earliest surviving bound books of the eighth century.

A thread-bound book is much easier to use than a glued paperback because the pages naturally fall flat when the book is opened, and thread-binding lasts far longer.

This second edition of Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping is dedicated to the memory of its author, who died earlier this year in the knowledge that work on a new edition was under way. The book is available to order on the AHS website via this link.

The unexpected visitor

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Almost exactly ten years ago I had John Harrison’s magnificent first marine timekeeper H1 in my workshop at the Royal Observatory. It was being dismantled for study, cataloguing and conservation for the new chronometer catalogue.

I had a film crew with me making a documentary, and they were becoming exasperated at constant interruptions to the filming. Finally another telephone call – a man was outside, asking if he could see me. Embarrassed, I assured the film team I would politely ask him to come back another time, but explained they had to come with me as I couldn’t leave them alone with H1.

Outside, the man apologised for arriving without warning and that he could come back if necessary. He introduced himself, offering his hand and just saying softly “Neil Armstrong”.

One of the film crew laughed and remarked 'Ha! I bet with a name like that you get lots of requests for autographs!' to which the unassuming gent simply replied: 'I’m afraid I don’t do autographs'.

It was at that point that we collectively realised that we were indeed in the presence of history. Suffice to say, all anxieties about filming schedules melted away and we all returned to the workshop (but with film cameras firmly switched off!)

Armstrong had long been a Harrison fan and he and his golfing friend Jim, hearing on the grapevine about the H1 research, had taken a detour from a sporting trip to Scotland, to make a pilgrimage to Greenwich.

For a wonderful hour or so we discussed Harrison and his first pioneering longitude timekeeper and it was clear Armstrong’s reputation was correct – reserved, yet of great intelligence and hugely well-informed; in short, a thoroughly nice man and not at all the showman one imagines when thinking of lunar astronauts.

I always asked visitors to sign my Visitors Book, but understood when Armstrong explained 'if you don’t mind, I’ll do it in capitals'.

Hearing that Harrison’s second prototype timekeeper, H2, would be next for research in the coming year, Armstrong returned and I spent a little more time with him, getting to know him a little better and was privileged to learn more of the Apollo 11 mission, from the horse’s mouth, as it were.

As he and Jim left on that occasion I asked Jim to sign my book again, and as they got back into their car, Jim whispered to me 'I think you’ll find Neil signed properly this time too'.

And indeed he had, something I shall always treasure.

Star of the show

This post was written by James Nye

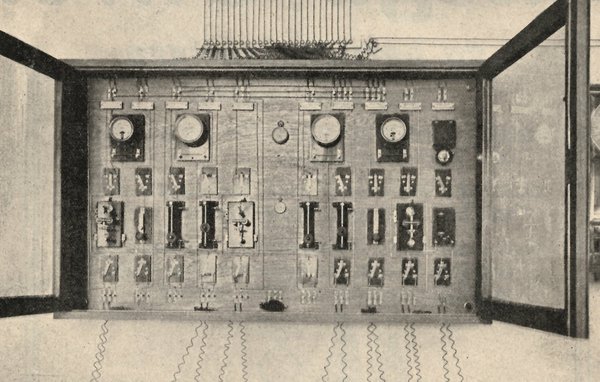

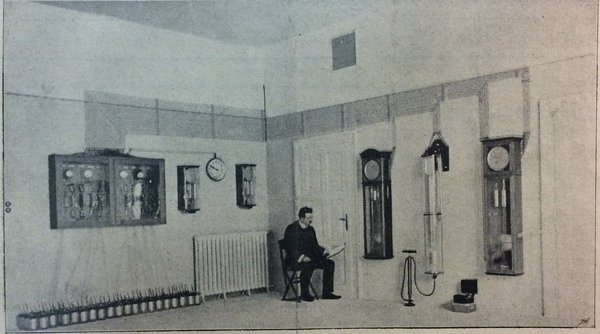

At the Mannheim electric clock fair, now in its twentieth year, one unusual item usually attracts a lot attention.

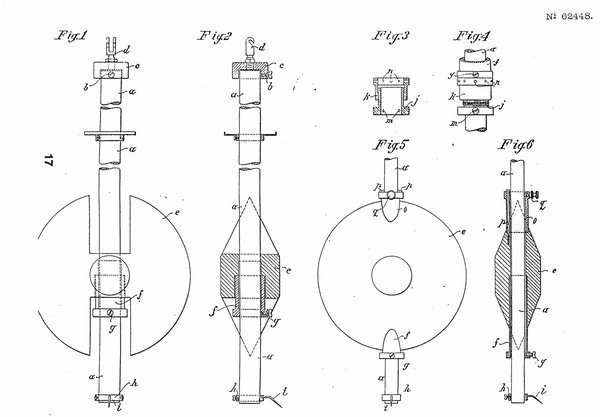

This year (2019) was no exception. The images show an early form of German ‘treppenhausautomat’, loosely a ‘staircase lighting timer’. Lighting, and therefore electricity consumption, has always been expensive.

An intriguing question, worthy of some serious research, is the economic justification for the complicated (and also expensive) electro-mechanical devices used (late 19th/early20th C) to reduce consumption.

In large houses, or multiple-occupancy blocks, it’s always made sense to add press-button switches to control stairwell lighting—the lamps remaining lit for a set period before being switched off.

Modern switches incorporate integrated circuits, but for a long-time such devices used a pendulum clock as the timebase.

The object here dates to c.1905, and was sold by Paul Firchow Nachfolger, from 3 Belle-Alliance-Strasse in Berlin. The clock mechanism is a standard volume production element, unsigned, and perhaps from Lenzkirch.

The hands are arranged to carry an adjustable set of contacts which will make a circuit, naturally for night hours, but with the capacity to set the operating hours (accommodating seasonal variations).

Assuming it is night (dial circuit closed), pressing a push-button in the stairwell will activate the motor below the clock, which in turn will revolve the drum.The drum has brass (conductive) sides, embraced by brass slide contacts.

The drum has a narrowed section, and when this arrives between the (wider) contacts, the circuit is broken.

The cycle lasts around three minutes.

The top panel shows ceramic entry ports for various cables: knöpfe (push-buttons), power, lampen (lamps), and two set of widerstand (resistance). The machine will switch 110V and up to 18 amps, so a significant load is possible.

The clock is a forerunner of more typical, volume-produced ‘black boxes’, but its complex form (and by inference its high cost) is a strong signifier of the importance placed upon saving money and controlling power use.

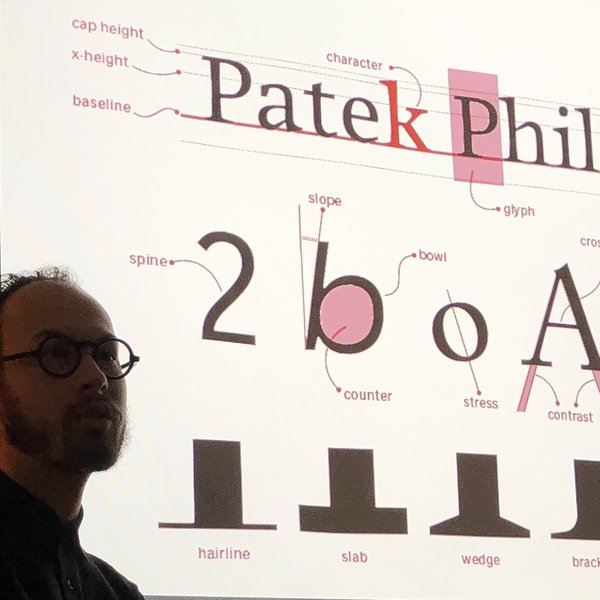

The typography of revival watches

This post was written by Mat Craddock

Until recently, there had been little research carried out on the typography of wristwatch dials. However, over the past decade, the increased interest in collectable vintage wristwatches appears to have sparked the interest of brands and collectors alike.

While wristwatch collectors’ focus has largely been on the variations in logo, layout and content of vintage wristwatch dials, interdisciplinary designer Lee Yuen-Rapati has taken a critical look at the typefaces used, and typographic decisions made, by watchmakers.

His Masters dissertation, titled ‘Motivating Factors In The Trends Of Horological Typography,’ formed the basis of an AHS Wristwatch Group talk at The Clockworks in April.

Lee’s research covered clocks, pocket watches and wristwatches, and looked at type and numerals used on the dials, identifying various themes and typographic pitfalls that appeared to be specific to wristwatches.

His research included interviews with brands and independent watchmakers about their typographical decisions, the typefaces they use and the importance of type design to their brand.

His talk focused on the typography of contemporary wristwatches that had revived distinct vintage or antiquarian styles.

Highlights included the use of system (or default) fonts by high end watch manufacturers, the technical limits of pad printing, the benefits and traps of modern processes involved in dial design (such as the digital workspace) and inconsistent choices made by watch brands when reviving older designs. Examples of recent wristwatches from Longines, Nomos and Stowa were used to illustrate these themes.

As a codicil, Lee discussed recent advances in dial printing, such as the use of physical vapour deposition on the zirconium ceramic dials of the Charles Frodsham Double Impulse Chronometer, suggesting that this technology might be taken up by other watch manufacturers, necessitating an increased focus on typographical principles and design choices.

Follow The AHS on Instagram: @thestoryoftime

Lee Yuen-Rapati: @onehourwatch

Mat Craddock: @the_watchnerd

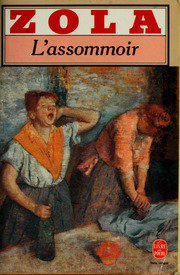

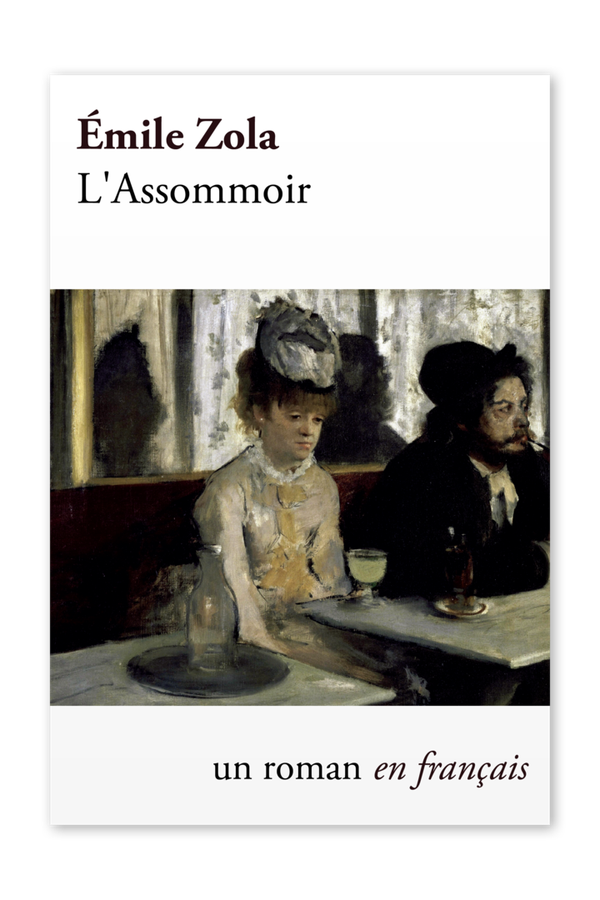

Dreaming of a clock in the slums of Paris

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every clock that left the workshop or factory on its way to a buyer has, we may assume, been coveted by and, we may hope, given satisfaction to its owner. But most of this goes unrecorded, and where traditional non-fiction sources are silent, we may find some glimpses in fiction.

For vivid descriptions of the life of the workers in nineteenth-century France one can do worse than turn to the wonderfully naturalistic novels of Emile Zola (1840-1902).

The book that shot him to fame in 1877 was L’Assommoir; below I quote from the most recent English translation: The Drinking Den , Penguin Classics 2000 rev. 2003, translator Robin Buss.

The novel depicts in graphic style the rise and fall of Gervaise Macquart, who worked as a laundress in Paris during the period 1850 to 1870. There are scenes of abject poverty and alcohol is a key character in the story; but there are also comical scenes and uplifting passages. It is a masterpiece. As one author has put it:

‘L’Assommoir is set in the dirt and filth of working class Paris, where life was hard and lives depressingly short. He researched in great detail the impoverished quarter of which he wrote, so that the work is an ethnographic novel and probably the first of its kind’.

In the poor household of the young Gervaise, a chest of drawers takes pride of place:

‘One of her dreams, which she did not dare mention to anyone, was to have a clock to put on it, right in the middle of the marble top – the effect would be quite splendid. Had it not been for the baby that was on the way, she might have risked buying her clock, but as it was she put if off until later, with a sigh.’ (p. 97).

Three years go by before she is able to act on her desire:

‘She had bought herself a clock; and even then this timepiece, a rosewood clock with twisted columns and a copper gilt pendulum, had to be paid off over a year, at the rate of five francs every Monday. She got cross when Coupeau [her husband] said he would wind it up, because only she was allowed to take off the glass globe and religiously wipe the columns, as though the marble top of her chest of drawers had been transformed into a chapel. Under the glass cover, behind the clock, she hid the savings book. And often, when she was dreaming about her shop, she would sit there, miles away, in front of the dial, staring at the turning hands, for all the world as if she was waiting for some particular, solemn moment before she made up her mind.’ (p. 108).

The ‘dreaming about her shop’ refers to her ambition to make herself independent and set up her own laundry, which indeed she eventually manages to do. Life looks good, she even entertains a large group to a celebratory dinner in the laundry shop.

But it was not to last, and as her life goes in a downward spiral, Gervaise is forced to bring one possession after another to the pawnbroker. She puts a brave face on it:

‘Only one thing broke her heart and that was putting her clock in pawn, to pay a twenty-franc bill when the bailiff came with a summons. Up to then, she had sworn she would starve rather than part with her clock. When Mother Coupeau [her mother in law] took it away in a little hat box, she slumped into a chair, her arms dangling, tears in her eyes, as though her whole fortune had been taken away’. (p. 279).

There is more horology in this novel. She also has a cuckoo clock, which would have been a much less valuable object, but it is never described in detail. Neither is the watch which only once makes an appearance, on the day that she is forced to put it in pawn as well:

‘The little knick-knacks had faded away, starting with the ticker, a twelve-franc watch, and the family photographs.’ (p. 384).

There is also a watchmaker who plays a small role in the story. In the courtyard of the tenement house where she lives are various workshops and shops, including – for a while – her own laundry shop:

‘At the bottom of a hole, no larger than a cupboard, between a scrap-iron merchant and a chip shop, there was a watchmaker, a decent-looking gentleman in a frock-coat, who was continually probing watches with tiny tools, at a bench where delicate things slept under glass covers while, behind him, the pendulums of two or three dozen tiny cuckoo clocks were swinging at once, in the dark squalor of the street, in time to the rhythmical hammering from the farrier’s yard’ (p. 134).

Literary critics may argue that in fiction, clocks and watches are often introduced as symbols, and that therefore novels do not necessarily give a realistic image of the ownership of clocks and watches.

Be that as it may, the story of the struggling laundress Gervaise Macquart, who dreamed of owning an ornamental clock and managed to bring one into her poor home, only to have to part with it again, feels very real indeed.

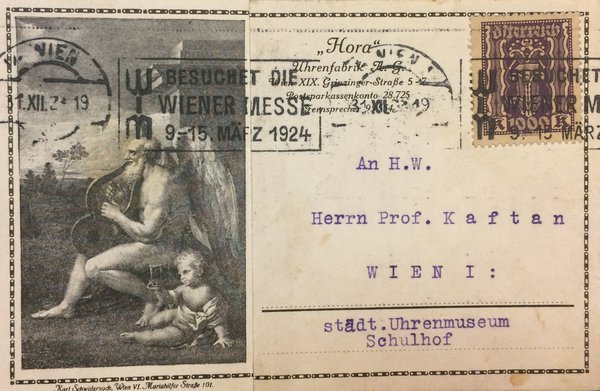

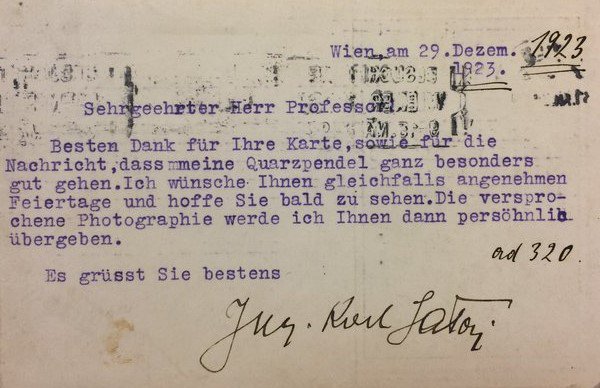

Mr Satori fuses quartz

This post was written by Tabea Rude, Vienna Museum

Around one hundred years ago, on May 15th 1918, the newly founded, not yet opened Vienna clock museum receives a generous present: a clock movement fitted with a fused Quartz pendulum rod.

It is installed in a most prominent position: right next to the entrance, in a case with a fully glazed front. Visible to every passer-by, it draws attention to the narrow house with its hidden treasures in the heart of Vienna.

This donation was the beginning of a long lasting correspondence between the clock museum’s director Rudolf Kaftan and the engineer, donor and inventor Karl Satori.

Originally from Hungary, Karl Satori is first mentioned in the proceedings of the international electrical society (Internationale Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft) in Vienna aged 24, explaining Lorentz electron theory.

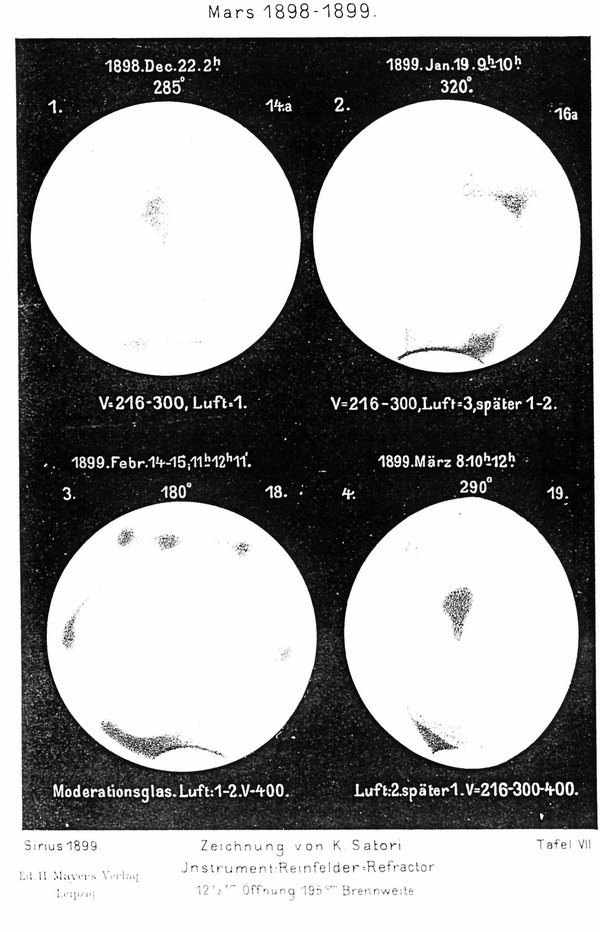

In the following years he delves into astronomical observation and planetary documentation and builds up professional relationships in the astronomy scene.

Soon he joins the international astronomical society and files his first patent in 1903: an electrical rewind system for clocks.

His professional career blossoms, allowing him to invest in his own private observatory in Vienna.

Around the same time, he is also given the opportunity by the Vienna electricity works to build up his own laboratory and to equip the Viennese Urania observatory with an electric time system which synchronized all public clocks in Vienna. This supplies the time signal as so called ‘Urania-Zeit’ to all telephone owners.

Besides his involvement in astronomy and several other clock related patents, he was also very keen in exploring pendulum materials and different methods of air pressure and temperature compensation.

Recognizing the unfortunate jumps steel pendulum rods experience during temperature changes and their reaction to magnetic fields, he experiments with fusing quartz into seconds pendulum rods. In 1912 he files his patent of the quartz pendulum.

One year later he opens his own precision workshop for mechanics and clock making. Satori expands, fuses quartz, files patents and ensures that the Vienna clock museum is placed to show the most cutting edge Viennese horological technology of its time.

Redisplaying the York automaton clock

This post was written by Daniela Corda

Over summer 2018, Matthew Read, Director, Bowes Centre, and I were commissioned to condition survey, part disassemble, pack for transportation, and reassemble an eighteenth-century automaton clock on behalf of York Museums Trust.

Originally assembled during the 1780s, this highly ornate clock was most likely designed for the export market and – although unsigned – has long been attributed to the London inventor James Cox (c.1723-1800).

The compilation of written and photographic condition surveying helped update museum records, inform current and future care, and outline operation options.

In its new permanent location in the Burton Gallery at York, the clock is on open display for the first time. Preventive measures were taken during reassembly such as the insertion of Melinex® film behind the case frets to restrict dust entering the case.

Under normal operation, the clock performs a 360-degree audio-visual show that includes rotating glass rods simulating waterfalls; automata pastoral scenes; spinning stars; jewelled contra-rotating flowers, and dancing cast-figures. In addition, the clock plays a sequence of seven melodies on a nest of eleven bells, striking the quarters too.

A detailed treatment report from York Castle Museum, dated 1982, indicates the clock has undergone many repairs, alterations and layers of reinterpretation, including the replacement of a pipe organ with a nineteenth-century Swiss musical box mechanism.

In its present state the clock has six main functions:

- Clock mechanism indicating hours, minutes, seconds, 1/5th seconds, date and age of the moon

- Quarter striking

- Hour striking

- Automaton musical train

- Automaton drive mechanism

- Swiss musical box

The majority of these dynamic elements are able to function, thanks to major renovation upon the object’s acquisition in 1974. So, although the clock can run, the overriding question is: should the clock run?

As the single dynamic historic object on show at the Gallery, running the clock adds tangible and intangible value for visitors, but comes at the cost of further cumulative damage. The present arrangement is to run the clock’s main movement, authorising the ticking sound, the hour and the quarter striking, but only to operate the automata elements at scheduled times.

Digitisation methods are being considered to build into wider conservation plans. Following prior research into microcontroller electronics, this object can benefit from implementing digital strategies such as recording audio aspects, reversibly relieving the mechanical movement from operation, and therefore wear, without experiential losses.

This ostensibly straightforward project highlighted inevitable emotional, mechanical, philosophical and conservation collections care questions. The clock can be seen at York Art Gallery with automaton demonstrations on Wednesdays and Saturdays, 14.00.

A clock to remember the Zeppelin raids over London

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

A recent article published in Antiquarian Horology, entitled ‘A Time to Remember’, focuses on a pocket watch in the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich that had been recovered from the Titanic, which sank in 1912 after hitting an iceberg.

The hands indicate 3.07, presumably marking the moment the watch entered the water.

The article discusses this and other watches recovered from the Titanic and can be read here.

I was reminded of this when recently I noted a board outside a tavern in the London district of Holborn, drawing attention to a somewhat macabre relic. The pub had been destroyed by a Zeppelin bomb in 1915, and a clock found in the wreckage, marking the time the bomb had struck, could be seen inside the pub.

Step inside, and there it is on the wall. Next to it hangs a clock that is in better shape but lacks its movement. In a show of solidarity, both clocks stand still forever.

The clock is mentioned in a list of ‘London’s top 10 timepieces – Time Out counts down our city‘s finest timepieces’, with this comment:

'When this snug corner-boozer was leveled by a Zeppelin bomb in 1915, one of the few things to be pulled intact from the rubble was the clock that today hangs to the left of the bar, hands frozen at the hour of doom. Locals say the clock can sometimes be heard to whistle, as though imitating the falling bomb. Bollocks, says the barman.'

And now for something different

This post was written by David Read

In the world of watch collectors there are many who dislike finding that a pocket watch case has been engraved with the owner’s name, or to record it being given as a present. My feelings are different. An engraving not only provides a date which can be useful information, but can also point to an interesting history.

Late one evening in November 2000, I was watching a BBC documentary about the Yukon Gold Rush when the name Skookum jumped out at me.

In turn, I jumped out my chair because some years earlier at a NAWCC meeting in Florida, I had acquired a 14 karat gold E.Howard & Co. pocket watch retailed by Joslin & Park of Denver Colorado.

E. Howard & Co. made some of the finest watches in America so it interested me, as did the inner back which was not the same colour of gold as the rest of the case. And engraved on it were the words, 'A relic of Skookum Gulch March 22nd 1897'. It was certainly something different.

When the Yukon documentary finished, some quick research on the Internet led me to an email address for the Yukon Prospectors Association and before going to bed I sent questions with attached images.

In due course I received a reply from a member, himself a prospector who had searched for gold and experienced the thrill of finding it.

The following summarizes what he wrote:

'Gold was first discovered at Skookum Gulch by Joseph Goldsmith and his partner on 22nd March 1897, the date engraved on your watch. Arriving in the Klondike area too late to stake a claim on one of the major creeks, he prospected the feeders and found rich gold in this one. Goldsmith staked the first claim and named the stream. He, or perhaps his partner, used some of the gold to have a replacement inner cover made for the watch. The gold will be from the original panning and is significant in that it marks an historical event'.

Two-timing

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The dictionary defines ‘two-timing’ as ‘to be unfaithful to a spouse or lover’ or ‘to deceive, to double-cross’. But that’s not what I want to talk about. What I have in mind here is people who put the clock forward even though they know it’s not the ‘real’ time. Perhaps we can regard this as another kind of cheating.

Some months ago I came across the term ‘Sandringham time’. British Summer Time – putting the clocks forward one hour in April and back again in October – was introduced in 1916, and among those supporting the idea had been King Edward VII (1901-1910).

Here (with thanks to David Rooney who supplied me with a scan of the relevant page) is what David Prerau wrote in his book Saving the Daylight: Why We Put the Clocks Forward (page 12):

'The king had recognized the waste of morning daylight and had already taken royal action: for several years, in order to have more time for hunting, he had been creating his own small sphere of daylight saving time at his palace at Sandringham, and in later years at Windsor and Balmoral castles, by having all the clocks advanced thirty minutes. (The tradition of ‘Sandringham time’ lasted until Edward VIII abandoned the practice in 1936).'

I was reminded of this when this week I finally got around to reading Flora Thompson, Lark Rise to Candleford , a semi-autobiographical series of three books giving scenes from a childhood in rural Oxfordshire in the 1880s and 1890s.

The books were originally published in 1939, 1941 and 1943, and then as a trilogy from 1945 onwards. I quote from the Penguin Modern Classics edition of 2008.

At the age of 14, the main character Laura (Flora) starts work as assistant in a Post Office. It is run by a woman, Dorcas Lane, alongside a blacksmith’s workshop which she had inherited from her father.

'The grandfather’s clock was kept exactly half an hour fast, as it had always been, and by its time, the household rose at six, breakfasted at seven and dined at noon; while mails were despatched and telegrams timed by the new Post Office clock, which showed correct Greenwich time, received by wire at ten o’clock every morning' (page 364).

The Post Office is re-introduced at the beginning of Part 3:

'As she followed her new employer through the little office and out to the big front living kitchen, the hands of the grandfather’s clock pointed to a quarter to four. It was really only a quarter past three and the Post Office clock gave that time exactly, but the house clocks were purposely kept half an hour fast and meals and other domestic matters were timed by them.

'To keep thus ahead of time was an old custom in many country families which was probably instituted to ensure the early rising of man and maid in the days when five or even four o’clock was not thought an unreasonably early hour at which to begin the day’s work.

'The smiths still began work at six and Zillah, the maid, was downstairs before seven, by which time Miss Lane and, later, Laura, was also up and sorting the mail' (pp 395-6).

In the first volume, when Laura is still a small child living with her family in a nearby hamlet, we find another interesting example of dual timekeeping.

One person in the hamlet, ‘Old Sally’, owned 'a grandfather’s clock that not only told the time, but the day of the week as well. It had even once told the changes of the moon; but the works belonging to that part had stopped and only the fat, full face, painted with eyes, nose and mouth, looked out from the square where the four quarters should have rotated.

'The clock portion kept such good time that half the hamlet set its own clocks by it. The other half preferred to follow the hooter at the brewery in the market town, which could be heard when the wind was in the right quarter. So there were two times in the hamlet and people would say when asking the hour: "Is that hooter time, or Old Sally’s?"' (p. 77)

Discovering a Japanese lantern clock

This post was written by Daniela Corda

As a Post Graduate Diploma student of the Conservation of Clocks program at West Dean College, one of my recent projects has been to restore safe working order to a Japanese lantern clock belonging to the Russell-Cotes Museum, Bournemouth.

Museum records classified the clock as Chinese, however, after conducting initial research, it became clear that the object conformed to many stylistic features of lantern clocks from the early-mid period of Japanese clock making.

Some of these features are indicative of the temporal time system employed in Japan during the country’s Edo period of isolation (1603-1868). It was not until 1873, during the Meiji Reform, that mean-time and the European calendar were adopted.

- Two-winged bell nut

- Deep bell

- Verge and foliot escapement

- Rotating 'warikoma' dial

- Latched case

- Posted iron frame and iron mobiles

The Japanese temporal system divides the day into 12 hours, rather than 24, and six of these 'hours' are proportional to daylight and six to darkness. Hence, the adjustable numerals are designed to accommodate variable time intervals within the relative lengths of day and night by season.

The numeral characters are engraved with the traditional 9-4/9-4 numbering, using the zodiacal names of the hours, which count down in reverse order.

During the process of recording and documenting, a conservation approach was employed focusing on stabilising the clock in its current condition. Treatment included fabricating missing parts and the mechanical removal of corrosion with a custom made mother-of-pearl scraping tool, a material that retains its shape but is softer than the substrate, so becomes sacrificial, reducing the risk of damaging the ironwork.

During Japan’s isolation, the temporal time system suited the predominantly agricultural society; concurrent competition in Europe for the longitude prize was not of their concern. Therefore, it is important to refrain from imposing western motives, descending from a precision-driven approach to clock making, onto an object that has come from a very different context.

Considerations for future work include analysis of the brass alloys and the coating used on the ironwork, as well as investigating the lacquer present on the calendar wheel (pictured above) aiming to provide a more detailed narrative of the social and craft context surrounding the clock. Due to its age a stable environment and restricted running hours will be imposed on the clock to mitigate further losses.

The popularity of horological tattoos

This post was written by Anna-Rose Kirk

Clocks and watches are the most tattooed image at the moment according to Vice magazine, and tattoo artists are sick of tattooing them.

'Clocks. Clocks, pocket watches and more clocks . Mostly on guys in their mid 20s. There must be hundreds, at the very least, being done in the UK every week. Lots of tattooists have stopped putting them in their portfolios because they’re so fed up with them' (Craig Hicks).

Time symbols have always been popular in art as reminders of the passing of life and the inevitability of death.

Hour glass tattoos have been a simple depiction of this for many years, and there has been a long tradition of symbolism within prison tattoos depicting clock and watches with no hands. However, the more recent need to capture time has sparked a trend of more complicated depictions and designs within larger tattoos often surrounded by banners, flowers, and owls.

Speaking to those that have the clock or watch tattoos, it is apparent that the most common reason was the idea of symbolising a date and time, a child’s birth for example, and was a way of avoiding text and numbers which have become a common tattoo choice.

Others wanted them as reminders that time is precious and had them tattooed in prominent places as a constant reminder to live their lives meaningfully.

One person I spoke to simply had a deep appreciation for horology and the way that watches worked after coming across them in his job in a jeweller’s and from his friends in the industry. Because of this, the time on the watch does not have a significant meaning, but it was important to him that the detail and the way it looked was right.

Celebrities and easy access to images and discussions play a part in tattoo trends but simply more people are getting tattooed meaning particular images seem to get used more often.

I wanted to get to the bottom of whether clocks and watches were seen as something mysterious with no concept of the inside workings, however, although a lot of the general public, especially the younger generation, does not understand the exact mechanics of a pocket watch, they have a tangible feel which in contrast to today’s sleek, minimal, computerised technology can feel a lot more real. They feel as if the have a history and a story; linked to memories tradition and ritual.

I wonder if a rise in nostalgia and a romanticism for craftsmanship and the handmade has brought about the rise of this style being used in tattooing and movements like Steam Punk.

It is perhaps a fight against excessive consumption of the 21st century and the dehumanisation of manufacturing and the idea that traditional skills may be lost. It seems to be that horology is being worn as a symbol of authenticity and a preservation of history in a vain attempt to show that this generation care.