The AHS Blog

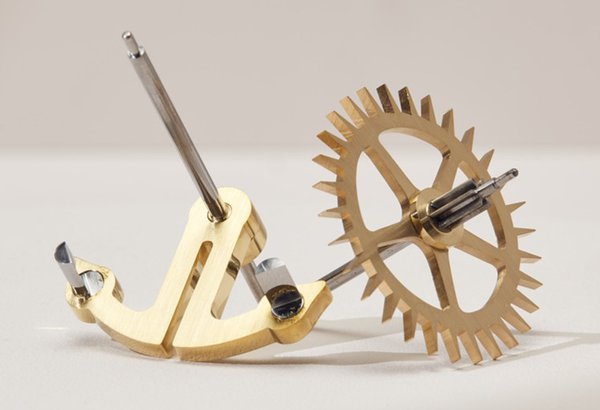

An animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement

This post was written by Eliott Colinge

Visual representation has always been a core means to learn about horology and explore its principles.

The literature provides countless invaluable schematics about escapements, repeating mechanisms and patents of all sorts. Less can be said about video representations. If an image is worth 1000 words, what can be said about a video?

The recent popularisation of 3D animation in the film and gaming industry has gathered a wide community of brilliant individuals giving their improvements to the field at an increasing pace.

It is hardly possible to have a conversation about 3D animation without hearing the word 'Blender'. Being open source, the software has attracted students, researchers, professionals and amateurs around the world and is increasingly becoming a standard in the industry. Blender is such an incredible playground and I am always in admiration of what gets produced by the community.

As a trained conservator of horological artifacts, I founded the animation studio 'Vecthor' to provide complementary 'non-interventive' solutions to help education around collections.

Vecthor has made available a series of short animations of escapements based on drawings and a YouTube video about Pierre Leroy’s marine watch (available in English and French).

Here is an example through an animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement used in his marine chronometers during the 1770s. The impulse energy is stored in the coiled springs (constant-force) and transmitted to the balance during its oscillatory arc.

Other escapement animations can be found on Vecthor's instagram: @vecthor_animation

A sad commemoration

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A couple of weeks ago, I attended Bob Frishman's NAWCC conference on 'Great Horological Collectors' at the Horological Society of New York's home in New York City – a wonderfully successful and interesting event. By good fortune the date of the conference came just before a short holiday we had planned in New York, with passage home on the Queen Mary 2 – a delightful way to cross the pond.

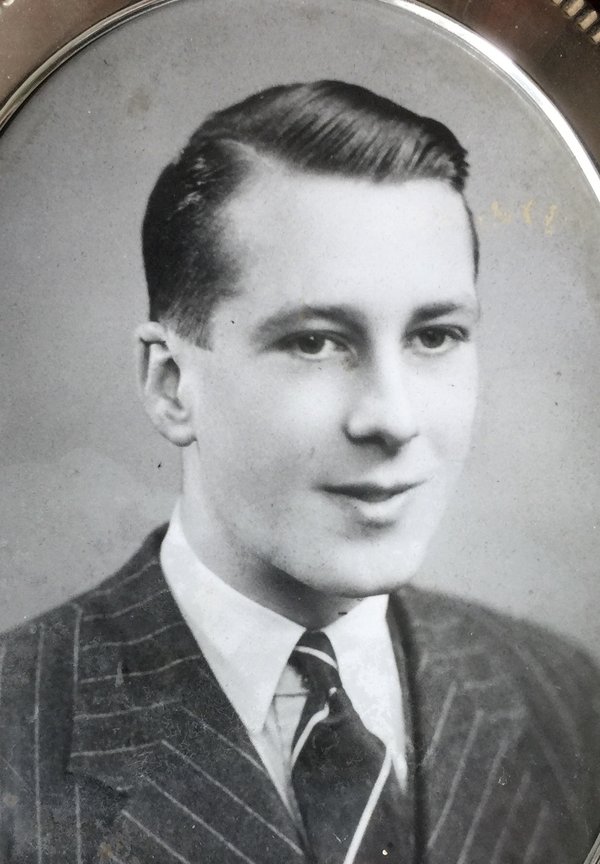

When planning the trip I realised that, by a rather extraordinary coincidence, during the transatlantic crossing there would occur the 80th anniversary of a family tragedy, played out in those very waters.

My Uncle Pat – my mother's brother – was serving on a merchant troop ship, the MV Abosso. On the evening of 29 October 1942, when the ship was travelling alone in the North Atlantic, it was torpedoed by a U-boat and sunk. 362 of the 393 passengers and crew lost their lives, including Uncle Pat, who was just 23 and had married only a few weeks before.

Just one lifeboat survived with 31 souls to tell the tale, some of them Navy officers who were aware of the detail of what happened.

The reason for telling this sad tale in an AHS blog is that there were two critical horological elements to the tragedy.

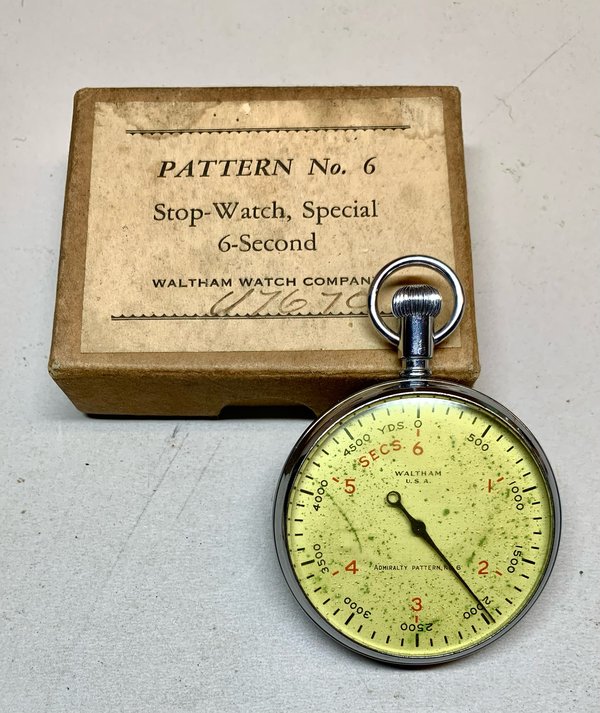

About 6 p.m. that evening, the master of Abosso, Captain Reginald Tate, became aware the ship was being tailed by a U-boat – U575, commanded by Kapitan-Leutnant Gunter Heydemann (1914–1986), as it turned out. The ship's crew was able to detect the submarine using ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) echo-sounding to determine the sub's bearing and distance, the latter by using an ASDIC chronograph.

The watch has a high frequency sweep-seconds hand on a dial recording up to six seconds, the time between transmission of the sound pulse and the echo determining the distance of the sub from the ship.

Having established precisely where the sub was, the ship's master had to decide what to do.

An option was to go full steam ahead and try to out-run the submarine, which would normally be possible – a submerged submarine makes much slower progress, though at a maximum speed of 14.5 knots, the Abosso was not a particularly fast ship.

The alternative was to adopt a 'random' zig-zag course so the U-boat could not predict the ship's position accurately enough to make it worth firing torpedoes at it, though zig-zagging naturally slowed down the progress of the ship considerably. The practice did generally work well, if maintained long enough, as U-boats had limited quantities of fuel and eventually had to head off for a rendezvous for refuelling.

Deciding not to try and out-run, but to zig-zag, the Abosso brought into action its zig-zag clock, a part of the navigational equipment on the bridge of WW2 merchant ships at the time.

A fairly standard ship's bulkhead clock is adapted to have an electrical contact at the tip of the minute hand, and round the periphery of the minute track on the dial is a metal ring with a number of moveable electrical contacts.

Each time the minute hand touches a contact it closes a circuit and a bell rings in the wheelhouse informing the crew to change course one way or the other.

If in convoy with other ships it is of course vital that all the ships adopt precisely the same agreed pattern of zig-zags, and when the instruction to zig-zag is given, the whole convoy would be signalled a secret code for the pattern to be used. The contacts on all the ships’ clocks would then be adjusted accordingly and zig-zagging would begin at a specific time, thus foiling the U-boats' attempts to align torpedoes with a target ship.

The log of U575 has survived, so we can also follow what happened from the U-boat’s perspective. Heydemann, a much decorated Commander in the ‘Brandenburg’ wolfpack in the North Atlantic, sighted the Abosso about 6 p.m. that evening. He was running low on fuel but decided to try and attack. Realising he was being traced, he went deep, out of reach of the ASDIC, but followed from a distance until he was nearly out of fuel. At that point, thinking they had lost the sub, Abosso’s master made the fatal decision to stop zig-zagging. Realising this, Heydemann risked running out of fuel and moved closer to the ship to attack.

Reading the U-boat's log today, and comparing with the U-Boat Commander’s Handbook (available as a translated reprint as E. J. Coates (translator), The U-Boat Commander’s Handbook, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, 1989) one discovers this was a textbook operation.

At 22.13hrs, Berlin time, one of the middle torpedos of four directed at the Abosso in a fan pattern struck the ship virtually amidships. The U-boat surfaced to inspect the target and Heydemann recorded seeing lifeboats being launched. One more torpedo was fired into the ship to deliver the coup de grace, and about half an hour later Abosso sank, U575 then departing to rendezvous for refuelling.

The one lifeboat which survived was picked up on 31 October by HMS Bideford, one of a convoy forming part of 'Operation Torch', heading for North Africa but, in the heavy seas at the time, no other lifeboats or survivors were ever found.

On the evening of 29 October this year, exactly 80 years later, and as close to the location of the Abosso’s sinking as I could estimate, I sneaked a centrepiece flower arrangement from our table after dinner and, against Cunard’s strictest rules, cast them into the sea at the stern of the ship.

A timekeeper had shown Abosso where the danger was, and the other timekeeper should have saved them. It is a sad thought that if only Captain Tate had left his zig-zag clock running just a little longer, the U-boat would have had to leave and 362 lives would not have been lost.

R.I.P. Uncle Pat.

High-frequency quartz watch fails to resonate

This post was written by James Nye

After the Second World War, Smiths pioneered rebuilding a watch manufacturing industry in Britain. It partnered with Ingersoll to make inexpensive watches in Wales, and developed high-grade watch manufacture at Cheltenham.

Despite achieving strong brand recognition, the economics never worked. Smiths lost money on every watch made at Cheltenham, subsidised from elsewhere in the business. Foreign exchange, material shortages, foreign dumping and more offered overwhelming challenges.

Into 1970 and the head of the clocks and watches division announced a plan to use Swiss watch movements, but in September 1970, Smiths’s CEO announced watch production would cease at Cheltenham, achieved by March 1971.

However, a small team under Dr Shelley of the Special Horological Products Unit continued the development of a cutting-edge quartz watch – the Quasar – launched at the Basle Fair in 1973.

A few hundred pre-production watches were produced. The senior Smiths staff tested them, and when I interviewed some of them ten years ago, a few were recovered from bottom drawers.

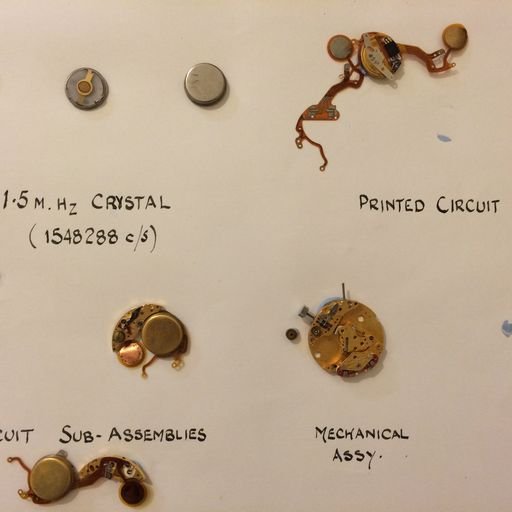

One of them was donated and is now in the Clockmakers' Company collection. Through similar generosity, the Clockmakers received a second watch, and also ephemera, including a rough card mounted with parts of the Quasar assembly.

Smiths used an AT-cut quartz crystal, not the normal XY cut. It resonated at 1.5 MHz, against the standard 32,768 Hz, and Smiths actually made this in-house, targeting high performance.

But this came at a price, in size, leaving little room for frequency division. Indeed, ‘conquering the division problem’ was the main achievement remembered years later by former senior Smiths managers.

Omega made a success of their 2.4 MHz AT-crystal watch, but bar or tuning-fork crystals of much lower frequency would soon dominate the mass market in watches by Timex and Junghans. Importantly, Seiko’s 38 Series watches had a frequency of 16,384, achieving better accuracy than the Quasar, with a frequency one hundred times lower!

Volume production of the Quasar never started – Smiths had stacked the odds against itself.

There were problems with the US supply of circuit boards, the stepper motors were hand-wound in Cheltenham, and in-house manufacture of the crystal was both expensive and inefficient.

Pricing was to be pitched at £70 in late 1973, but while watches were still being tested on the wrists of senior management, the chairman and MD of Smiths visited Seiko’s factories, and what they saw convinced them to pull the plug on the Quasar.

Until fairly recently, Quasars had remained essentially invisible – almost mythical. But at a remote auction, a Cheltenham watchmaker's effects turned up. Even if Smiths stopped work in 1973 or so, at least one person kept testing the pre-production samples.

Tags record watch 485 with crystal 419, and watch 365 with crystal 365, faults being found, and adjustments being made.

While the fossil record retains little evidence of a watch that never made it to market, some evidence of its development has nevertheless been preserved.

Clocks in Lisbon

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Any horologist visiting Lisbon will want to visit the Casa-Museu Medeiros e Almeida, situated just off the majestic Avenida de Liberdade: https://www.casa-museumedeirosealmeida.pt/

It is the house where the Portuguese businessman António Medeiros e Almeida (1895–1986) lived and which he filled with his private collection of objects of decorative arts, including a collection of clocks and watches. It opened as a museum in 2001.

As explained in the catalogue, which I reviewed in Antiquarian Horology in December 2019, it 'consists of a core of about 650 items. [...] The timepieces cover a period of five centuries and are from France, England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Portugal, Russia, China and Japan'. A special gallery was created for them, but clocks are also found in many other rooms.

However, I want to direct you to two other clocks elsewhere in the city.

The first is in the Military Museum, a distinctly old-fashioned – but to me rather inspiring – place; some photos can be found on http://www.exercito.pt/pt/quem-somos/organizacao/ceme/vceme/dhcm/lisboa. On display in one of its enormous rooms is a turret clock with a plaque explaining (I translate from the Portuguese):

'Constructed in Lisbon in the 18th century by the clockmaker F. Baerlein, it was the only turret clock in the neighbourhoods of Santa Apolonia, Santa Clara, Alfama, and surroundings. It commanded all the clocks in the various establishments of the Royal Armoury of the Army, and also serving the population of the nearby areas as well as the crews on the ships on the river Tagus. After being struck by a grenade in May 1915, it stopped functioning. It was repaired in March 1957 […], which the staff of the Military Museum have marked with this plaque.'

A web search found nothing on the maker. What I did find was a photo of the base of a lamp post in Lisbon with the name F. BAERLEIN. Clearly later than the clock movement, but then, perhaps Baerlein had successors in the city?

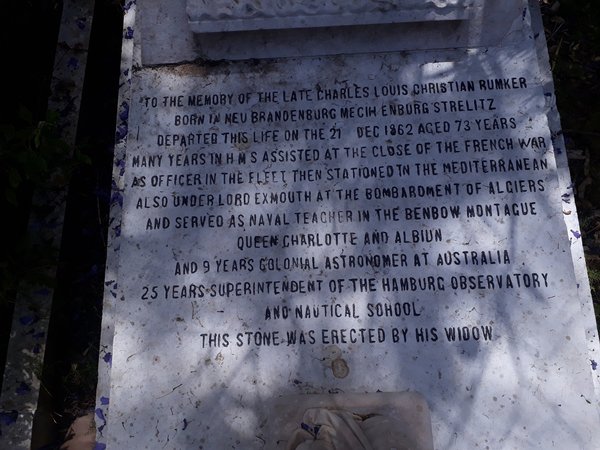

For the second clock, one must enter the beautiful British Cemetery https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/ located opposite the Estrela Park. Tourist guides invariably single out the memorial to the author Henry Fielding (1707–1754), best known for his novel Tom Jones. But to me of far greater interest is the memorial erected for the German-born Charles Louis Christian Rümker (1788–1862) https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/interesting-monuments which was the subject of an article by Julian Holland in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society No. 77 (2003), pp. 32-35.

Rümker served as colonial astronomer in Australia and later as superintendent of the Hamburg Observatory and Nautical School, and the monument shows the tools of the astronomer, including a clock.

While funerary monuments often show an hour glass, symbol of the passing of time, the representation of a clock is certainly rare, perhaps even unique? I would be interested if anyone knows other examples.

The humpback carriage clock

This post was written by William Oke

I have just finished studying on the Horology undergraduate course at Birmingham City University. For my final project, I built a humpback carriage clock and this project allowed me to research surviving examples of these to inform the design, gathering as much information as I could to create a record of those clocks. These are some of my findings.

Abraham Louis Breguet and his son, Antoine-Louis, produced many fine travel clocks including the silver-cased ‘pendule portiques’ that were sold between 1812 and 1830 [1]. Features that are included in nearly all humpback carriage clocks can be traced back to these, including silver engine-turned dials, Breguet’s iconic hand style and a number of complications necessary for travelling such as alarm, calendar work, and moonphase for travelling at night. I have been able to find records of eight of these in various collections.

There are also contemporary examples by the brothers James Ferguson Cole and Thomas Cole. During his life, Cole was called the 'second Breguet' [2]; he made several complex humpback carriage clocks with retrograde astronomical work; the earliest example is from the year of Abraham Louis Breguet's death, 1823 [3]. There is a detailed description of this clock in the first volume of the Horological Journal from the time, which also states seven more were made in the subsequent 30 years [4].

The English tradition of producing these clocks was continued by the London clockmaking firm Jump. The earliest example I have been able to find was sold by Ben Wright, hallmaked 1878 [5]. This clock was made for Francis Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke, and three further humpback clocks were ordered from Jump by the Baring Bank partners Barons Northbrook, Ashburton and Cromer.

Until this Revelstoke example appeared on the market, the only other of these four whose whereabouts was known was the one made for Ashburton, which came up for sale at Sothebys in 1998. Interestingly, the Ashburton clock was described in a letter to Colonel R. Quill from A. Hayton Jump (great-grandson of the company's founder, R. Jump), who designed 'the last dozen' of these Jump humpback carriage clocks:

“the first of these clocks was made for a Lord Ashburton of the Victorian period before I was in the business. It cost the firm a load of money in time and trouble, for so many men had to make so many parts (the man that made the hands couldn’t do anything else, etc. etc.). My father presented the bill to Lord A with trembling hands and apologised for the high charge. Lord A took the bill and wrote out a cheque at once for double the amount charged on the bill!!! And expressed his appreciation.” [6].

The most recent examples of humpback carriage clocks were produced in the mid-20th century, firstly by Philip Thornton who made several in the immediate postwar years including one that was commissioned by Charles Frodsham & Co. to be presented to Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (who was also in possession of the Breguet pendule portique, No. 2806) [7]. It is likely the last humpback carriage clock was made by Quill and J.S Godman in 1963, which was based on the clocks by Thornton.

These historic examples are rare but have been seen to come up for sale fairly regularly; there is no doubt that their pleasing design and the fine craft skill they display leave them as popular today as when they were first made.

Footnotes:

- Daniels, G., 1975. The Art of Breguet. 2021 ed. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, pp. 78-79.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, p. 112.

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, pp. 134-135.

- Ben Wright Clocks Ltd, 2016. Jump, London. https://www.benwrightclocks.co.uk/clock.php?i=105 [Accessed 3 May 2021].

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd, pp. 289-90.

- The Royal Collection Trust, n.d. Carriage clock 1947. https://www.rct.uk/collection/2943/carriage-clock [Accessed 18 April 2022].

The creation of 'A General History of Horology'

This post was written by James Nye

Winston Churchill wryly commented, ‘Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy and an amusement. Then it becomes a mistress, then it becomes a master, then it becomes a tyrant. The last phase is that just as you are about to be reconciled to your servitude, you kill the monster and fling him to the public.’

The emergence of Oxford University Press’s General History of Horology has echoed some of these observations. The editors do not necessarily agree, but I believe it was first in a bar in Pasadena, during the 2013 NAWCC conference on ‘Time for Everyone’, that Anthony Turner first broached the idea of a major work on the history of horology. I think everyone smiled politely.

Years later, in October 2016, he asked me if I would help, as his ideas were formulating and he had already managed to get Jonathan Betts interested in collaborating. However, both of us told Anthony that we were heavily committed, and I can see our emails were more than a bit tentative.

In June 2018, Anthony was back in touch, as he had now convinced OUP to get on board with the project. We met at a London hotel in July that year, and over a convivial and euphoric dinner Betts and I agreed to get fully on board as advisory editors and a firm proposal went to OUP.

August 2018 saw the beginnings of establishing the wider team of authors. The book ended up with thirty-five writers, though originally there were more.

In November 2018, OUP came back with comments from the external referees who had examined the proposal. One of them was hoist with his own petard when Anthony insisted that the referee himself fill a gap that he had indicated in the work.

A manuscript delivery deadline was set at December 2019. A draft contract emerged in January 2019, between OUP, the editors, and each contributor, eventually signed off in August 2019.

By May 2019, authors were beginning to discuss chapters with each other. It was at this point – when the euphoria had faded – that I recall joint authors were beginning to admit to each other they had bitten off what seemed like more than they could chew.

Helpfully, there were positive discussions with Sotheby’s on sponsorship. This allowed us to have colour illustrations throughout and a professionally compiled index.

Over the following months, draft chapters were beginning to fly around. Some of these were written in other languages, and needed translating to English. And more than a few were penned by Anthony himself, of course.

We had eight chapters in all by September 2019, but at this point we were also losing authors, who realised that other commitments stood in their way. And other authors were commenting, ‘Yes, I really must get down to some work!’

Unfortunately, one scholar from whom we had hoped to have a lengthy contribution died even before we could invite him. Health problems held up contributions from others.

The submission deadline shifted to late February 2020 to give us a chance to edit the whole work and to submit in turn to OUP in October that year. In January 2020 we were still scrabbling to find authors to fill a few missing parts of the jigsaw, and the timetable was under pressure. Chapters kept arriving, again some needing translation by Anthony, and some drastic editing as at least two were twice as long as required.

Eighteen chapters were in by mid-February, but as a contributing author as well as an editor, I was beginning to feel a bit of pressure myself!

The fateful month of March 2020 arrived, bringing Covid. More material arrived, but another author was lost owing to external commitments, necessitating further re-arrangement. By May we had to increase discipline significantly, since we had so many chapters on board, and three editors considering them – version control was vital.

If there had been excuses before, lockdown removed them all, and towards the end of the year the last of our contributions were coming together. It was early November 2020 that we finally had the whole book in draft, and much of that month was taken up in sorting images and securing consents.

We began considering a cover in early 2021 and realised that it was necessary to look beyond accurate representations of any clocks or watches. Thus, the idea of commissioning a bespoke artwork from Lee Yuen-Rapati emerged.

In February 2021, production work on the book began in earnest. We saw first proofs at the beginning of July, and the second half of the year was taken up with gradually ensuring that myriad small corrections were made.

In early December, we realised that there were major problems with the index that had been provided, and the work had to be restarted. Tragically, Paulo Brenni, one of our authors, unexpectedly died.

We finally had a complete and workable index by mid-January 2022, with OUP sending all the files to the printers in February, while the paper actually ran through the presses on 28 March. It was then that the physical production of a slipcase managed to sabotage the timetable, and books only finally started arriving in late June.

It was quite a ride along the way. I see my computer has 27GB of material relating to the project, and at least 1,300 emails. Anthony’s statistics will be larger, given his role as General Editor.

Our aim was to offer a truly international treatment of the subject. In production it was also international. The book was written in nine countries, edited in England and France, designed and typeset in India, indexed in England and printed in Scotland.

But at least this global monster has been killed – we trust the public finds the struggle worth it.

You can order the book here. Use the promo code ASPROMP8 to save 30 per cent.

The two videos of the book being produced are courtesy of Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow.

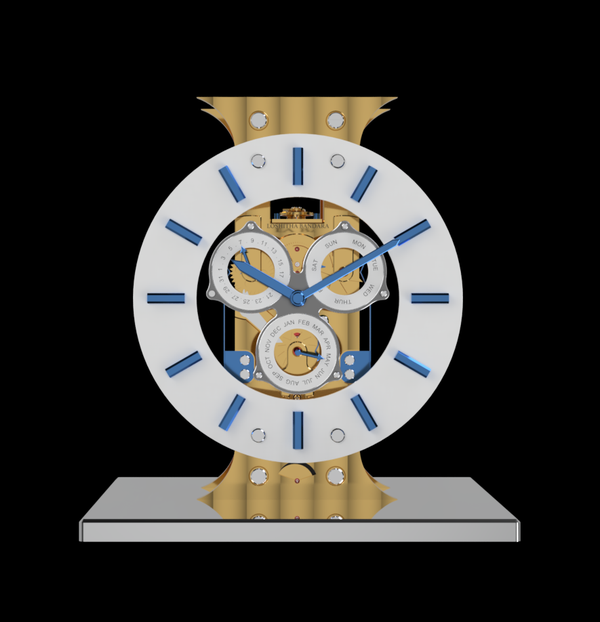

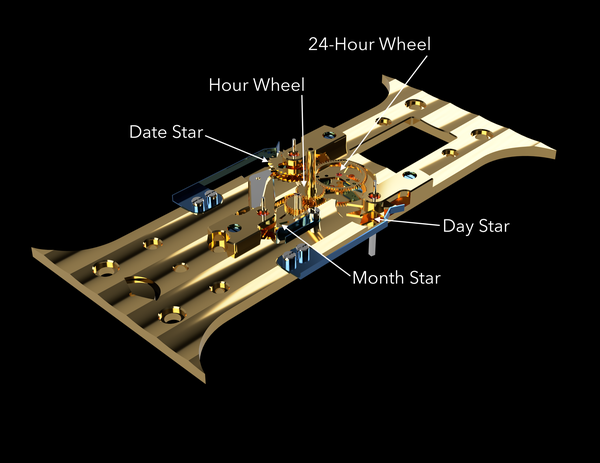

The AHS Birmingham City University Prize 2022

This post was written by James Nye

At the Birmingham City University School of Horology awards evening on 16 June, the AHS BCU Prize was awarded to Loshitha Bandara for his outstanding final-year project, a skeletonised mantel clock with triple calendar and power reserve indication, inspired by F-P Journe and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Many congratulations from the AHS! Winning this award with such an accomplished clock is a clear signal that we should watch out for Loshitha who no doubt has an amazing career ahead of him.

The clock is a tour de force, involving a range of finishes including engine-turning, Geneva stripes, perlage, straight-graining and guilloche.

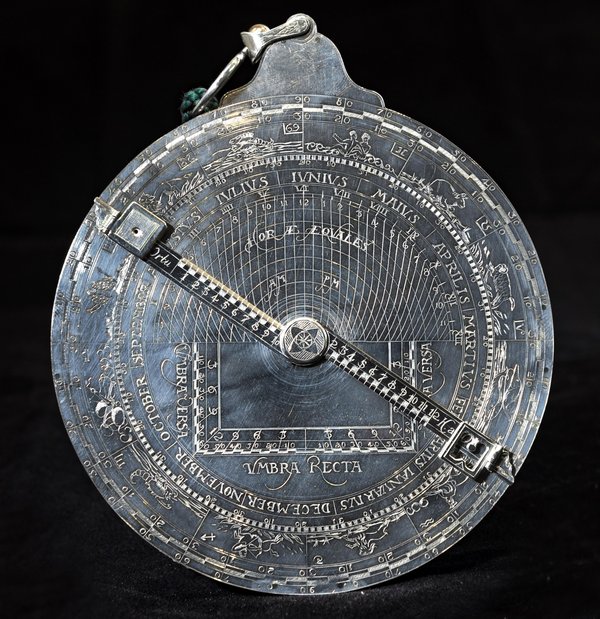

The Ivanhoe Astrolabe

This post was written by Andrew Miller

Recently I re-discovered (in a drawer) a piece of work that for me is ancient (30 years) but for the type of work is quite new (less than 500 years). It might be of passing interest to members.

It is solid state and largely untroubled by mechanical disturbances. Its accuracy should not deteriorate significantly over the next few hundred years.

It is a 1988 reworking to a smaller scale of an Arsenius astrolabe. Arsenius worked in Holland in the 16th century and is one of the great astrolabe makers. The original would have been a brass instrument some 11" diameter; this is 110mm and made of silver, ebony and copper.

The era has been updated to the current era, whereas many astrolabes are calibrated for an era some 2000 years ago when the fixed stars and constellations were first placed around the ecliptic. This is handy for using the instrument today although astrologers prefer the ancient calibration because the stars are in the 'right' place relative to Sun and planets.

The device was the must-have techno-gadget for cool dudes in the late 1500s. It will show current time and date if you have celestial sightings and the positions of the fixed stars and Sun if you have a time and date.

It will calculate not only the equal and unequal hours (the latter used in medieval times before reliable clocks were widely available) but also the height of tall buildings.

The face of the instrument has the standard rete (web) and rule through which the latitude plate can be observed. Four latitude plates are included inside the instrument and are engraved for five northern latitudes. The reverse has the calendar and zodiac on a 360 degree scale which can be used with the alidade for sighting the altitude of the Sun and fixed stars as well as predicting their altitudes.

Made in 1988 after I had spent some months at sea on the sailing yacht 'Ivanhoe' and had ample time to star-gaze under unpolluted skies. So I call it the Ivanhoe Astrolabe.

Inspiring people with horological collections: a guide’s perspective

This post was written by Robert Lamb

Since October 2015, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection of clocks, watches and associated objects has been displayed in its new home at the Science Museum, where it is accessible to the public whenever the Museum is open.

I have been conducting 60-minute tours of this wonderful historic collection on a monthly basis since July 2019. Despite needing to pause during the pandemic when the museum was closed, myself and the other volunteer guides have been back up-and-running since October 2021 and we hope that the frequency of the tours will increase as more volunteers join the team.

So, what happens on my tours?

Firstly, I introduce myself to the group and enquire if anyone has any specific interests. Participants are a pretty eclectic mix of those who, by chance, saw the notice at reception, those who came especially to see the collection, inquisitive tourists, and passers-by who show an interest and I cajole to join!

I then explain that we will not cover the whole collection, but will be honing-in on specific objects and groupings or significant topics and people.

I always like to give a short introduction to cover the origins of the collections, history of clockmaking and development of London’s Livery Companies.

Having gauged the mood and interest of the group (not forgetting that children may need entertaining too!), we often start with the introduction of domestic clocks in Europe and London, followed by the later need for more accurate timekeeping. Often, we look at the introduction of the pendulum and I talk about the development of clocks in London with the knowledge brought back by John Fromanteel. We are regularly drawn to John Harrison and his fight for recognition to win the Longitude Prize and then become fixated by H5!

There are so many tales to tell of the many objects we encounter. I love the one of an early Master of the Company, whose role was to keep the Company chest (which contained the silver and significant documents) at home during his tenure, but couldn’t get it through his front door!

No two tours are ever the same, which gives me great pleasure and I hope it does this for the participants.

Joining a tour is the only way to see what actually happens – visit the fabulous collection yourself and soak up the wonders of such a diverse horological history!

A curious dial in a south-London cinema

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

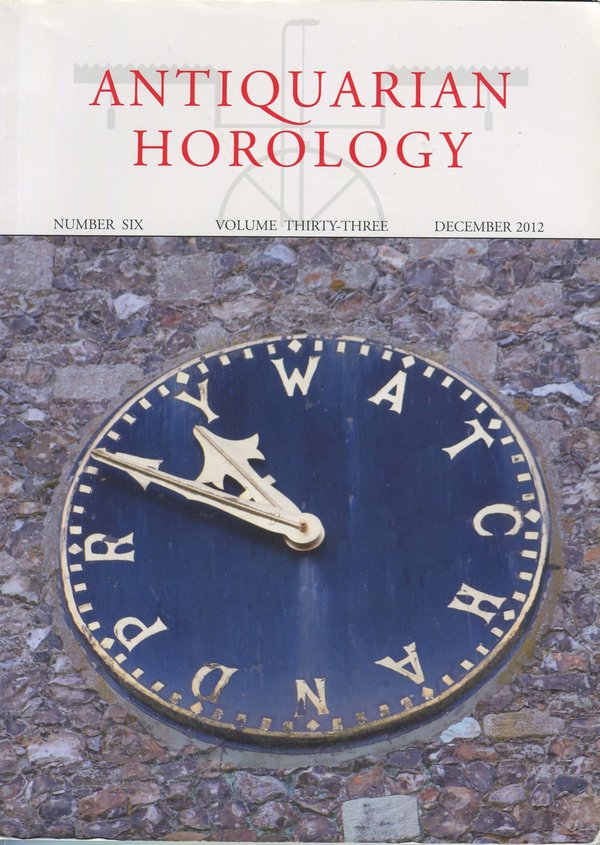

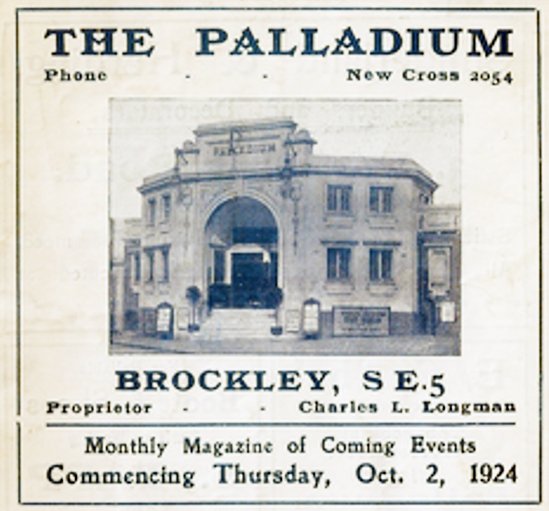

In a blog 'Letters on the Dial', posted 8 November 2012, I drew attention to dials that instead of hour numerals have letters. These can range from the name of the owner – I showed watch dials with the names Thomas Stevens, George Catling and James Catling – to a biblical quote, as seen on the dial illustrated on the cover of a journal issue.

A while ago I read the first novel of the novelist and literary critic David Lodge (born 1935) called The Picturegoers, originally published in 1960. The story is set in a London suburb called ‘Brickley’, which closely resembles Brockley and New Cross in south London where Lodge grew up. It depicts the lives of a number of people of varying ages and social backgrounds who live there and go to the same local cinema, called the Palladium, on Saturday evenings.

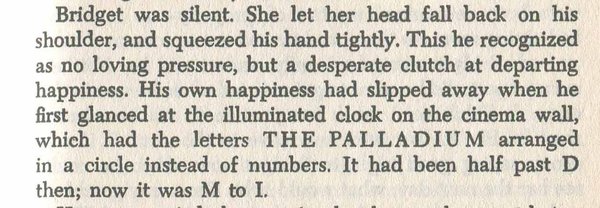

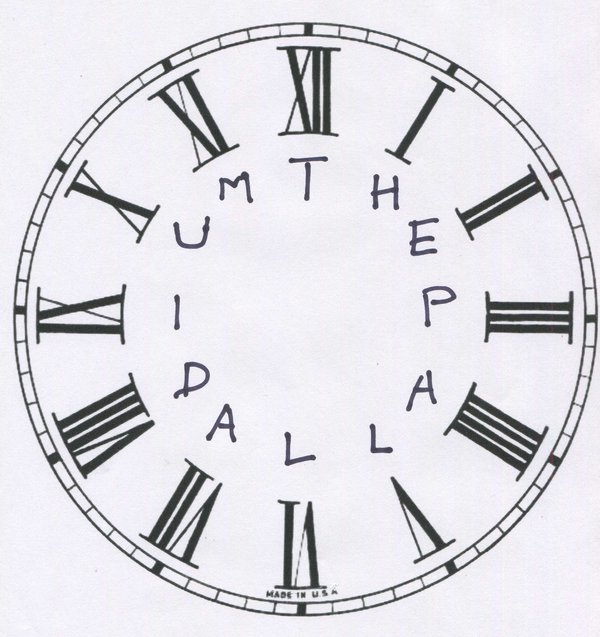

One of the characters is a young lad who takes his girl to the cinema but can hardly enjoy it as he is fretting about whether he will be on time to walk her home before his own bus, the last of the evening, leaves. 'His own happiness had slipped away when he first glanced at the illuminated clock on the cinema wall, which had the letters THE PALLADIUM arranged in a circle instead of numbers. It had been half past D then; now it was M to I'.

There was a picture theatre in Brockley named Palladium Cinema from 1915 to 1929 and New Palladium Cinema from 1936 to 1942. It was then renamed Ritz, closed in 1956 and demolished in 1960. (http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/27905). It is tempting to think that the young Lodge saw the dial there – surely he wouldn’t have made this up? I have written to the publishers of my edition of Picturegoers, Vintage, asking them to forward my question to the author, but to date have not heard back. One wonders whether others old enough to have visited the Ritz recall seeing the dial?

.

The clock and watchmakers of Kilwinning

This post was written by Heather Upfield

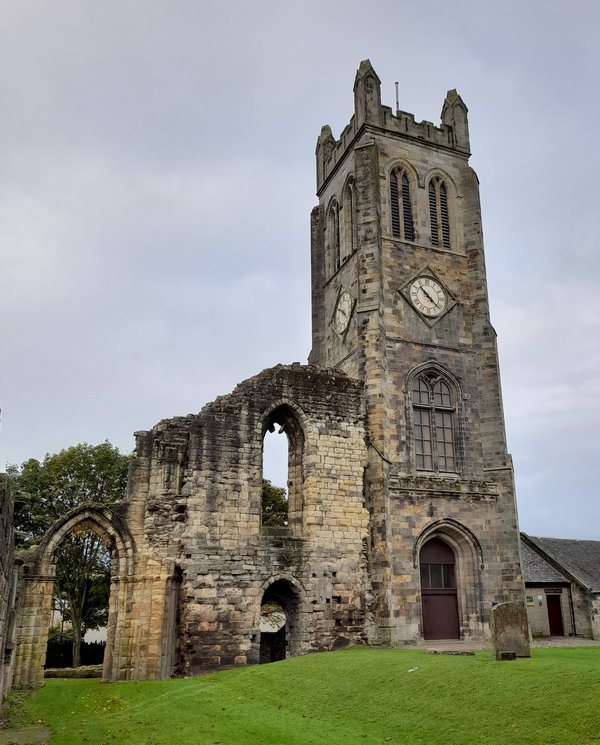

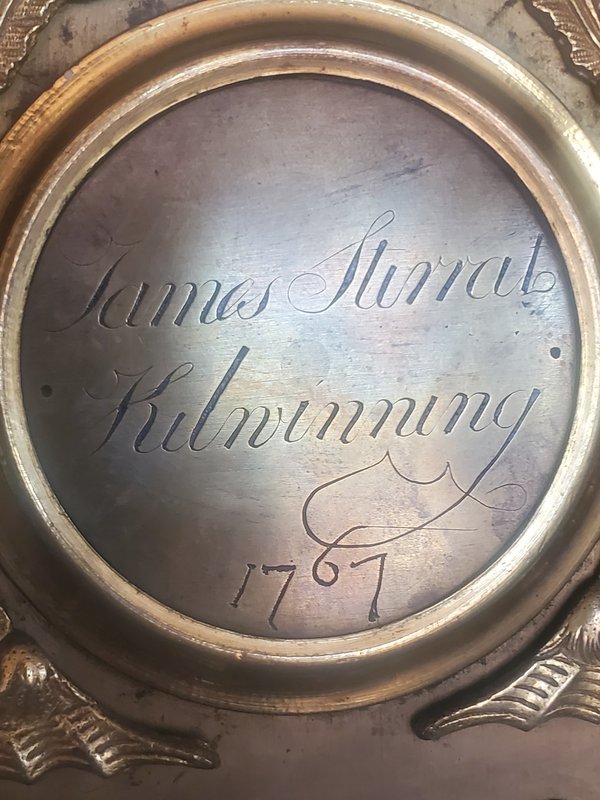

Kilwinning is a little town in south-west Scotland, which grew around the twelfth century Abbey (now in ruins). Following the collapse of the one remaining medieval tower in 1814, a new Abbey tower was built in 1816. James Blair, Kilwinning clockmaker, was commissioned to make the turret clock. As an interested local resident, I undertook research into James Blair for Kilwinning Heritage, in 2019.

The project grew exponentially, with a study of Whyte’s (1) compendium of around 8,000 people involved in clockmaking in Scotland. I discovered that James Blair was not the only Kilwinning clockmaker. There were eight men providing an almost unbroken stream of clockmakers in Kilwinning, from the mid-eighteenth century into the early twentieth:

James Stirrat longcase (1767-1790); James Blair longcase and turret (c1802-1836); David Loudon (c1836-c1850); William Allan longcase (c1816-1850); Hugh Millar longcase and turret (?-1860); James Gibson longcase (1867-1882)(2); Andrew Johnstone watches (1870-1893); and William Torry longcase (c1882-c1911). Years given are dates of trading in Kilwinning.

What makes this so significant for Kilwinning’s history is the fact that while much is known of the local large-scale industry (mining, brickmaking, the ironworks), clockmaking was a hitherto unknown and undocumented industry and trade, taking place at street level. It produced a seemingly extraordinary number of clockmakers for such a small town (population 1,934 in 1820). All of this information, plus the three Kilwinning turret clocks, was published by Kilwinning Heritage as Time Piece (3) in 2019.

Following publication, we have been contacted by several people from Scotland, England, and as far away as Vancouver, Canada, and Nevada, USA, all of whom, miraculously, own Kilwinning-made longcase clocks. We would be delighted to know if there are any other Kilwinning-made clocks and watches out there. If you have one in your possession, or know of others, then please contact Kilwinning Heritage at kh2011@hotmail.co.uk. We look forward to hearing from you!

References

- Whyte, Donald (2005). Clockmakers and Watchmakers of Scotland, Mayfield Books, Ashbourne, Derbyshire

- James Gibson closing shop and William Torry taking over, Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald, 15 July 1882. www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000962/18820715/025/0001. Accessed 7 August 2019

- Upfield, Heather (2019). Time Piece: a history of James Blair and the Clocks, Clock & Watchmakers of Kilwinning 1719-2019, Kilwinning Heritage, Kilwinning www.kilwinningheritage.org.uk

Photography

Abbey Tower and James Blair turret clock: Heather Upfield

All other photographs: Current clock owners. Reproduced with kind permission

A prize-winning project 2021

This post was written by Iolanda Clopotel

My name is Iolanda Clopotel, and I have recently completed my degree in Horology studied at BCU in the School of Jewellery.

Our last and major task within the course was designing and manufacturing, from stock, a clock of our own design. This project allowed us to explore and put in practice the knowledge and skills learned in the previous years, and I have chosen to make a clock inspired by the French drum movements, featuring a Brocot escapement.

Learning more about the design of this escapement was a wonderful experience, and I am happy to have succeeded in making a working escapement by the end of the course, both in reality and in the virtual environment.

I was lucky enough to achieve the highest scoring marks in my year group and I would like to thank LVMH Watches and Jewellery for the wonderful prize in the form of a beautiful chronograph that I will wear with pride from now on, as a reminder of my own achievements.

I would also like to thank the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers for their award which will be very useful in completing future and on-going projects.

I feel grateful for the people and companies that support and reward new horologists that are just entering the field and help in keeping the passion for always improving the craft skills of precise timekeeping.

Decaying clocks

This post was written by David Rooney

I need your help!

In the final chapter of my new book, About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks, I tell the story of a plutonium timekeeper made by the Japanese electronics firms of Matsushita (now Panasonic) and Seiko in 1970 and buried in a time capsule beneath an Osaka park. It will keep time, and keep ticking, for 5,000 years.

A single gram of radioactive plutonium in the form of an oxide, wrapped in gold foil, steadily decays by alpha radiation, emitting helium nuclei into the clock’s gas chamber, which expands like an accordion’s bellows as a result. As the bellows expand, they pull the clock’s hand around the dial. You can read all about the Osaka time capsule project here.

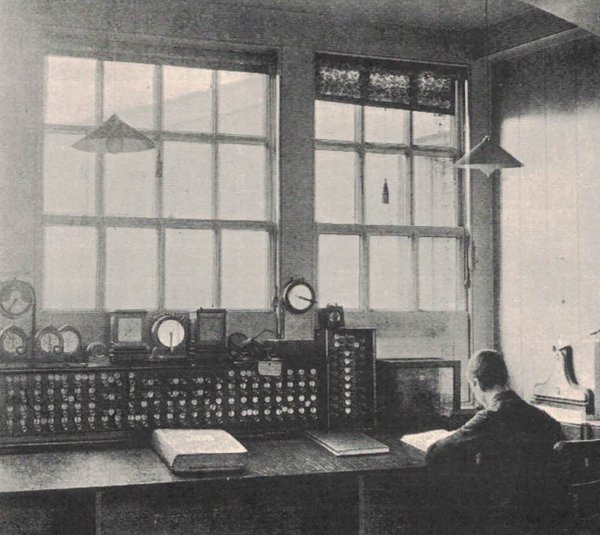

I had never previously encountered radioactive clocks! I have spent several years studying the history of atomic clocks – the ones that use caesium, rubidium, or hydrogen – but these exploit resonance, not radioactive decay, as their time-base. So, I got interested in this new (to me) horological technology and have started digging further.

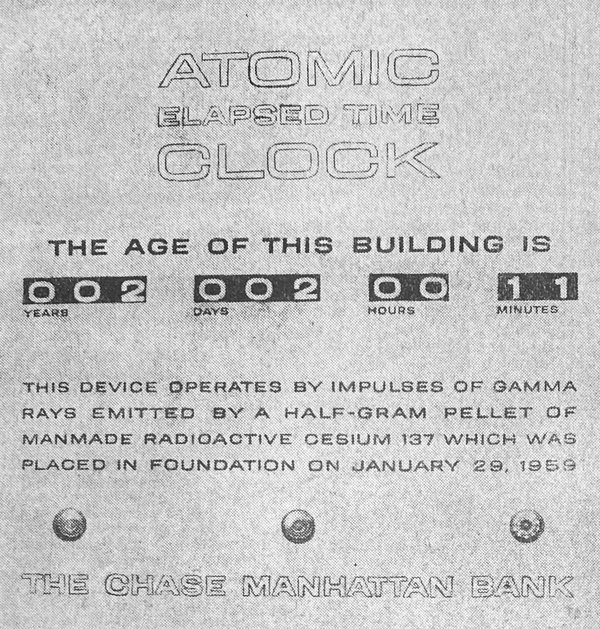

In 1959, the mayor of New York unveiled a clock at the Chase Manhattan Bank that uses gamma radiation from caesium-137 atoms to keep time. Each gamma ray detected by a Geiger tube sends a pulse of electricity to an amplifier and counter. Made by the US firm of Associated Nucleonics, it was claimed to be able to run for 200 years.

Six years later, the Benrus Watch Company filed a patent for a nuclear wristwatch using the beta radiation from technetium-99 or boron-10. In 1968, the Bulova Watch Company submitted plans for a clock that employed alpha radiation from plutonium-242, uranium-233 or neptunium-237. That one was apparently built. And in 1971, the Hamilton Watch Company’s parent body applied for a patent on an alpha-particle wristwatch using radium-226.

Here’s where I need help. Do you know of any other radioactive timekeepers, or more about the ones I’ve described here? Do you have any reference material, press cuttings, images or research reports that shed light on this novel technology? And is there a wider context I am missing – was the Chase Manhattan clock a PR exercise for the emerging civil nuclear industry, or is there a different explanation?

If you have any information about radioactive-decay clocks that you’d be happy to share with me, I’d love to hear from you. My contact details are on my website. Thanks!

'About Time: A History of Civilization in Twelve Clocks' by David Rooney

This post was written by Chris Andrews

The sentence 'David Rooney has written another book' is one that should make ears prick up.

Rooney, longstanding member of this society and previously of the Science Museum and Royal Museums Greenwich, has already written one short but enjoyable and informative book about Ruth Belville, a history of mathematics to tie in with the Zaha Hadid-designed gallery in the Science Museum, and a monograph about the political history of urban traffic congestion.

His latest book may prove to be the most influential so far, and on the 16th of July over two hundred people gathered virtually on Zoom to hear David give an AHS London Lecture to tie in with its publication (AHS members can watch it here). There are innumerable books presenting the history of timekeeping and even more presenting history in general, but About Time is a rarity for considering how – in the author’s words – 'the story of time is the story of us'.

As someone who is not nearly as skilled in practical horology as some members of the society, I have gravitated towards the historical aspects of the subject. (Of course I do still, in the words of one of our founding members, 'love to watch the wheels go round'.) Those innumerable books about the history of timekeeping have given valuable insights into the innovation and development that has given us the masterpieces that tick in our hallways or on our wrists, but the subject of what those timekeepers mean to us and our lives has so often remained un-tackled.

Not so here, Rooney dives head-first into stories of how clocks have been used to enforce order, fight wars, shame the idle, make money and dream of peace.

I spent a while thinking about how best to describe the field About Time sits in – it is not strictly a history book, nor a technical work about clockmaking – and in the end, it seems like it deserves a new word. My suggestion would be that it is sociohorology, and long may this line of enquiry continue.

Looking inside a Renaissance table clock

This post was written by Víctor Pérez Álvarez

One of the oldest horological artefacts kept at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich is an astronomical table clock made in Augsburg around 1586.

The clock is known to historians of horology, but some interesting findings came to light when it was dismantled in 2017 for a research project funded by a Caird Fellowship granted to me. The clock was partially examined and cleaned at the British Museum in 1967. Then some pieces were dismantled and kept in a separated box, including the count wheel, two chains and three paper washers. There is nothing unusual with these parts, except that the washers have been cut from a scraped drawing, which sparked our curiosity.

The then curator Rory McEvoy began to take apart the clock and another similar paper washer was uncovered under one of the dials. It didn’t help us to identify the drawing, but the mystery was about to be solved. When taking apart the movement, Rory unscrewed a brass bridge and two bigger fragments came to light, this time with a recognizable head: it was a playing card! A clockmaker folded a jack of diamonds and cut it out to the shape of the bridge to fit it in place.

Lots of questions come to our minds immediately: Who put these fragments in the clock and when? Why playing cards? How old were they?

We contacted Paul Bostock, member of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards and playing cards collector. Mr Bostock kindly visited Greenwich to see the fragments and he established that were Parisian playing cards from the 17th century!

What is the strangest thing you found inside of a clock?

Stinky horology

This post was written by Tabea Rude

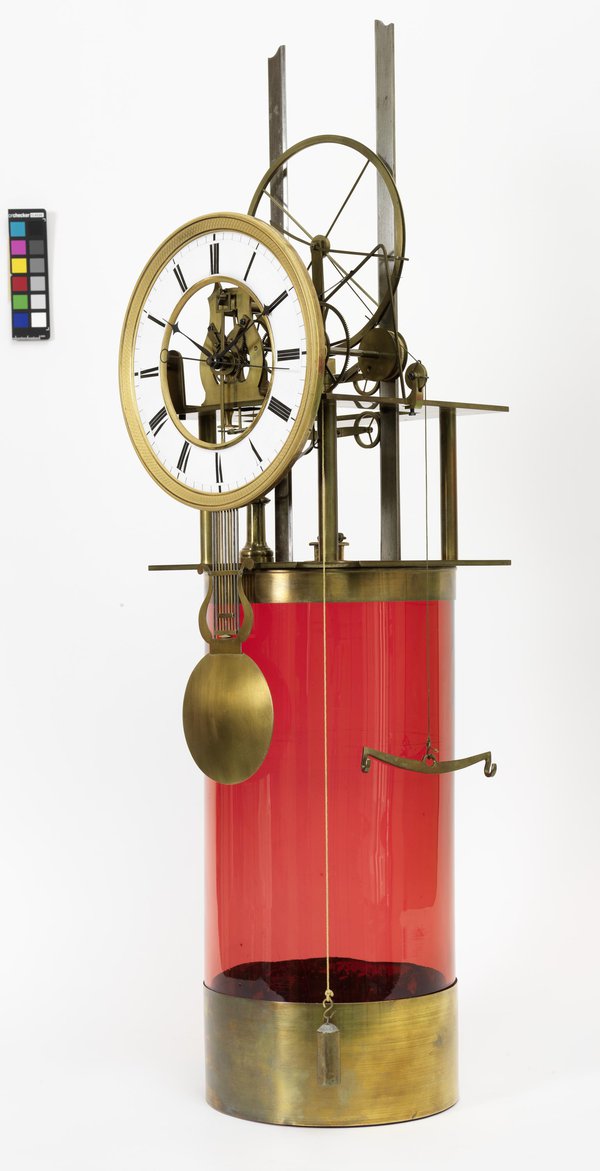

Not many clocks can claim a major olfactory experience by nature of their operation, but this one must have done: the hydrogen clock by Pasquale Anderwalt (1806-1881).

It is mentioned from the early 1840s onwards in several German publications. Anderwalt was a mechanical engineer and worked in Trieste. He developed machines for agricultural use and received a privilege for improvements on windmills. In the 1850s, he was involved in finding and proposing solutions for the frequent shortages of drinking water in Trieste.

For that reason, he was sent to the 1851 World Exhibition in London, to find out what the department of hydraulics and the gathered experts from all over the world had to offer. He also brought his hydrogen clock for presentation. Quite a number of these curious hydrogen clocks survived. Some readers may have seen one of these on display in the Clockmakers Company Collection at theScience Museum. Another is found in the Vienna Clock Museum, with three further examples in museum storage in Vienna and Trieste.

All of them have this rough idea in common: The glass cylinder is filled with sulphuric acid, the owner adds zinc and closes the lid. The zinc then reacts with the sulphuric acid to hydrogen, pushing a piston upwards, which in turn rewinds the weight.

Anderwalt himself claims that 'one ounce of zinc will last the clock machine at least for a human life span'. Probably a very trendy machine in its time, it could definitely compete with other alternative power ideas and not-so-perpetual-motion-clocks. Articles about these have been published in a number of Austrian, Moravian, Italian as well as Bavarian newspapers and scientific reviews. It is not known how many of these objects exploded during use or how smelly they really were.

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

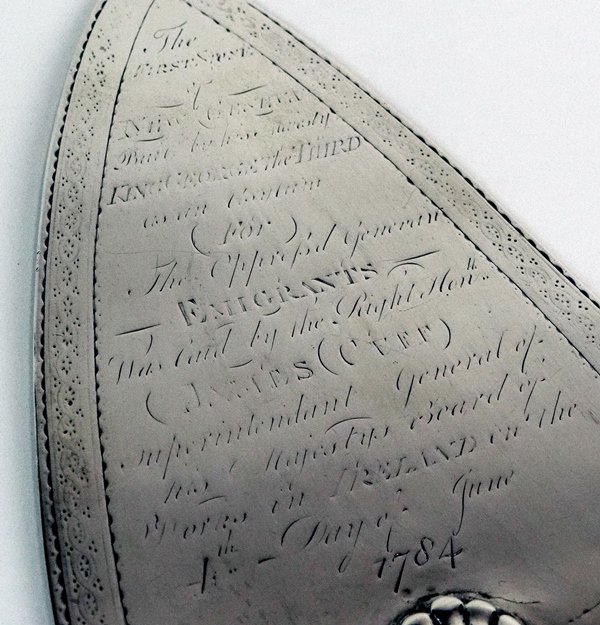

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

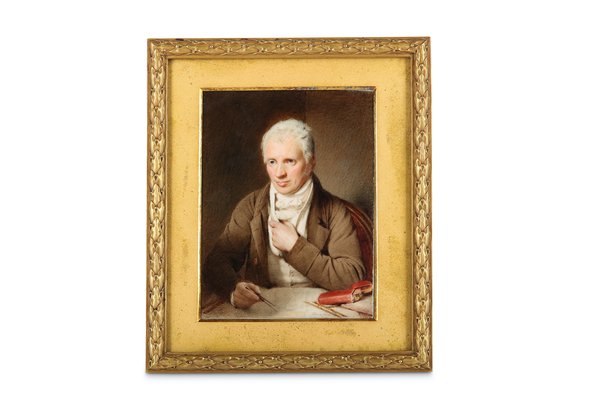

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

The No.4

This post was written by Jonny Flower

It’s really not every day that a dealer in horological objects gets to make a once-in-a-lifetime report. But, to the door of number 4 Lovat Lane, London, residence of the AHS, to convey news of a handsome discovery! Buried under decades of dust in a darkened room it has been found! Behold…the Synchronome No. 4, which came to me as part of the estate of an electrical engineer.

In photos it looked like it might be a self constructed version, especially with the blue Hammerite paint on the frame. Upon seeing it however, it was obvious that it was factory built.

It was smaller and more delicate than usual Synchronomes and the carvings in the upper door frame were sunrise style, not floral. A very early Hit and Miss synchroniser shows that at some stage it was connected to another Master clock, possibly a Shortt tank.

Once the synchroniser had been removed the bronzed NRA plate engraved with the magical No.4 appeared, one of the very first production Synchronome one-second master clocks.

No pilot dial was evident. The movement had separate footed cocks for the count wheel, latch and the gravity arm. The coils were attached to an L-shaped projection from the main frame casting. The pendulum has a typical steel trunion with adjustable brass sleeve, delicate brass weight tray and a nicely made lead filled bob with small brass shaped rating nut. The impulse pallet was of a shape I had not seen before with stepped sleeve, lipped tip and a separate screwed on support plate for the gathering wire and jewel.

The mahogany case was a design that was used for the early prototype clocks with brass frames and used before the adoption and incorporation of pilot dials.

After all these discoveries I consulted friends and colleagues together with all the books and literature to establish where No.4 sat in the time line of Synchronome production. What came to light was that there was a fundamental change in the construction of the one-second master clocks very early on in their production. In Bob Miles’ excellent book on Synchronome he had noticed this too.

This first series of numbered production models I am going to call the Interim Series. The Interim Series of one-second master clocks can be distinguished as follows:

Frame: We know from physical evidence that from serial number 4 up to and including number 41 the cast iron frame had an L-shaped protrusion to support the coils and armature pivot plate.

Movement: Footed brass cocks are used for the Count wheel and gravity arm. The latch used until 1920 is positioned on an adjustable brass frame that is screwed to the back plate.

The back stop is a jewel with a coiled spring-like counterweight that pivots through a pillar attached to the inside of count wheel cock.

No.4 has a case that was used for the brass movement prototypes with a narrow trunk, pediment top and sunrise carvings in the upper door frame. Uniquely at this point in time it is the only one with a door that has the hinges located on the left hand side. No.41 Has a flat topped case with glazed sides. I believe that this Interim Series was a very small production run of approximately 50 pieces with smaller cases and no pilot dials.

My thanks go to John Fothergill and James Kelly for their help, and of course to the late Bob Miles. I am pleased to report that No. 4 will soon be joining the collection of The Clockworks museum in South London.

A musical romp in an antique clock shop

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

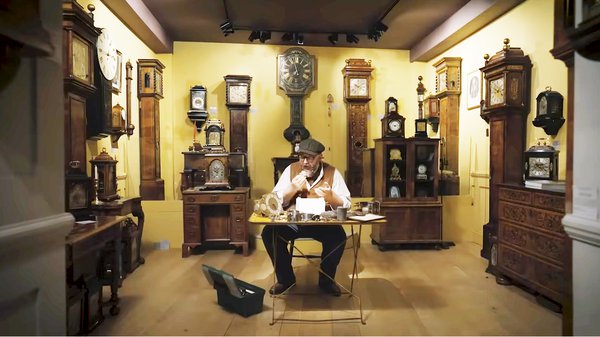

Howard Walwyn deals in fine antique clocks in Kensington Church Street, London. While his shop was closed for normal business due to the Covid crisis, he allowed it to be used for a remarkable musical entertainment: a filming of Maurice Ravel’s comical opera L’Heure Espagnole.

First performed in 1911, the opera is set in a clockmaker's shop in eighteenth-century Toledo. The title can be translated literally as ‘The Spanish Hour’, but the word heure more importantly means ‘time’ – ‘Spanish Time’, with the connotation ‘How They Keep Time in Spain’.

It is the story of a clockmaker and his wife, who hopes to have some private pleasure in the hour her husband is out winding the municipal clocks. However, the presence of a muleteer (here modernized as a UPS courier) who came in to have his watch repaired throws a spanner in the works.

It is a delightful romp – a farce – with two would-be lovers hiding inside the cases of long-case clocks (the pendulums do not appear to have been in the way!) and both ending up being persuaded to buy a clock after the clockmaker has returned.

For more information and a synopsis of the action, see here.

The opera is sung in original French with English subtitles. It is a small affair by opera standards: just 50 minutes long, and only five characters, no choir. It was pre-recorded in the Wigmore Hall in London, and the (excellent) singers acted out their roles in the shop. In this small-budget production the orchestra is replaced by a piano, but that doesn't detract from the pleasure of seeing and hearing it performed with such gusto.

The opera has been staged regularly since 1911, and will undoubtedly have many more performances. But it will never be repeated with such an abundance of authentic ‘props’ as can be seen in this entertaining video recorded in Howard Walwyn’s shop.

Stories of an everyday timepiece

This post was written by Andrew Hyatt

I'm a 1st year student at Birmingham City University, studying for a BA in Horology. One of the things that interest me in horology as a student are the stories that timepieces can tell. Whilst the world changing events of John Harrison’s H1 through to H5 or the exciting life of Larcum Kendall’s K2 do make for fascinating reading, I am talking about the story every timepiece that I hope to end up servicing will tell me.

This story is not necessarily the emotional attachment that the owner undoubtedly has to the item. That can be interesting, but in taking apart one of my first clocks I found what I consider to be a much more interesting story.

The clock shown below is a mass produced 2 train clock with a rack striking mechanism. I picked it up because I loved the art-deco style case and the unusually shaped dial.

It is clear that several other people also did as when I took the movement apart my initial observations found a couple of things, the first is that at some point the pendulum suspension spring has been replaced. Both the rod and the back cock have been bent to accommodate a new plastic topped spring shown below.

This made me a little worried about the rest of the mechanism with what appeared to be a quick fix to get the clock running again, but as I continued I found evidence of what may have been a more caring hand. The back cock also shows evidence of the escapement/crutch arbor pivot hole having been re-bushed with the finish almost invisible on the acting face. One of the click springs has also partially sheared, but then its been re-blued.

This tells the story of one or more people that got this clock running again and I am excited to add my name to that list, hopefully in a less noticeable way, as this clock continues its story.