The AHS Blog

All aboard the Vitascope: a clock with a view

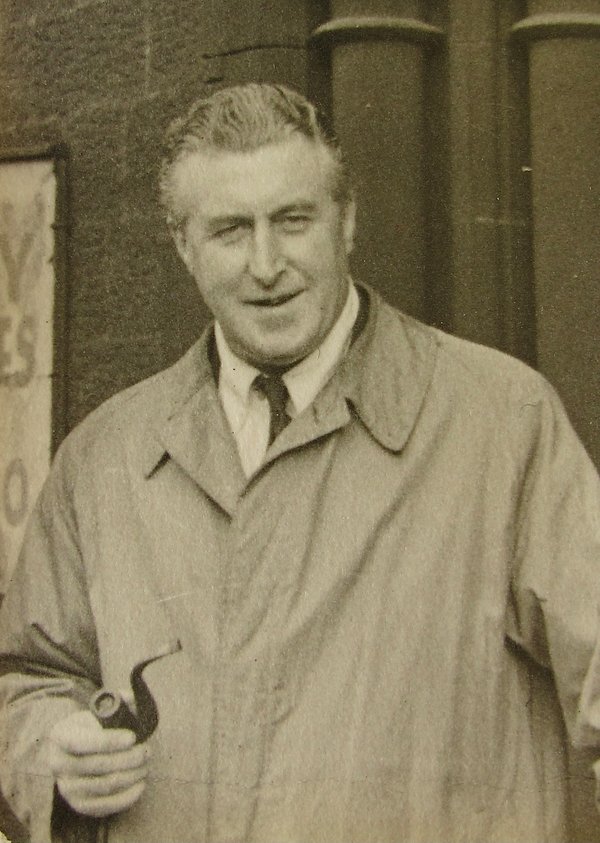

This post was written by Geoff A. Horner

Ever stumbled upon a clock that's more than just a time-teller?

Meet the Vitascope Illuminated Panoramic Electric Clock, a delightful creation from the Isle of Man that has been charming enthusiasts for over 70 years. Forget boring old tickers; this beauty features a miniature sailing ship that actually pitches and rolls on a painted sea, all while the sky behind it magically shifts from sunrise to sunset and moonlight.

Manufactured by Vitascope Industries Ltd between 1946 and 1958, these clocks were truly a product of their time. They were part of a post-war boom in plastic injection moulding, and while they might not have had 'real horological content' according to some, they certainly had real character. The Vitascope seems to attract the interest of even those who are uninterested in clocks.

Joseph Frederick Summersgill, the inventor and managing director, clearly had a flair for the whimsical. Beyond the clocks, Vitascope Industries also created sought-after flying saucers and other plastic novelties.

What made the Vitascope so popular? Its unique, animated diorama and the fact it came in a rainbow of colours. Plus, being mains synchronous, it was accurate and never needed winding – a true convenience for its era.

The Vitascope was marketed worldwide, as its developing patent history indicates, and, as the press noted in 1948, ‘the factory is working at top pressure just now on the Vitascope dioramic electric clock which is finding a ready market in different parts of the world’ (Ramsey Courier, 19 March 1948, 7).

While you might hear claims of them being rare, Vitascopes actually pop up for sale quite often. However, finding one in pristine condition can be a treasure hunt! They came with variations in case colour (from common creams and browns to rarer greens and reds), different hands, and varying chapter rings. Early models often featured specific combinations, like a cream case with brass studs and 'Empire State' hands.

The Vitascope is a testament to inventive design, proving that a clock can be a conversation starter and a miniature piece of art. It's a fun and fascinating glimpse into mid-century design and a reminder that even everyday objects can hold a touch of magic.

The conservation of precision horology

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A few weeks ago I attended a fascinating international three-day conference on the conservation of historic regulators and chronometers, hosted by the curatorial and conservation staff at Palermo Observatory in Sicily, part of the INAF group (Instituto Nationale di Astrofisica) of Italian observatories, all of which have historic collections of instruments and timekeepers.

The lectures, which were presented by specialist curators and conservators from Italy, UK, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, covered a great range of horological subjects from philosophical preservation, practical conservation of collections and a more general discussion of the care and preservation of these especially vulnerable objects.

Although the various papers reflected quite different perspectives, all the speakers found common ground on the principles of care and spoke with one voice on the aims of their roles as custodians of our historic collections.

A particular aim of the conference, discussed in depth in the final group meeting, was to formulate a common set of guidelines for future curators and conservators, and an internet forum was then established to continue the dialogue in future.

The hosts at Palermo Observatory, Ileana Chinnici and Maria Carotenuto, to whom we were especially grateful for organising the event, were particularly keen to seek advice from delegates on formulating a programme of care for the fine collections at Palermo. This might then apply to all the historic precision instruments in the Italian observatories under INAF.

We learned some fascinating statistics:

-- these instruments represent 80 per cent of the astronomical heritage in Italy, and 10 per cent of these objects are timekeepers of one kind or another;

-- in all the various observatory collections there are 53 clocks, 31 chronographs and 12 box chronometers;

-- 25 per cent of the horological material is of British manufacture, 20 per cent is Swiss, 13 per cent is Austrian/German, 7 per cent is French, and 35 per cent is Italian.

Naturally the regulators at Palermo formed the focus of much interest and discussion during the conference, and what fine things they are! The stellar list of makers includes Mudge & Dutton, Janvier, Vulliamy, Cumming & Grant, Frodsham, Dent and Riefler.

Palermo Observatory had been founded in 1790 with Guiseppe Piazzi as its first astronomer. It was Piazzi who, on a visit to London and Paris in the late 1780s, commissioned the regulators from Mudge & Dutton, Cumming & Grant and Janvier as the first timekeepers for astronomical use at Palermo.

Having recently studied and written about the works of Alexander Cumming (Antiquarian Horology, March 2022), I found the example by Cumming & Grant, which has Cumming's own form of gravity escapement, of particular interest. It is very similar to the regulator signed by Grant only, in the Clockmakers' Company Museum in the Science Museum, London, both clocks being of superb quality.

A really interesting and valuable three days; there will hopefully be a chance to return soon to study this fine collection more closely.

The various rooms in the historic building now form the museum of the observatory, which can be visited in person or virtually.

Ringing in the New Year

This post was written by Andrew Strangeway

As a clockmaker, or practising horologist, there is one particular moment while waiting for a clock to strike when time seems to slow down.This moment is more daunting when the streets outside are lined with 100,000 people and millions more are watching live on television, and streaming, waiting to hear the clock chime.

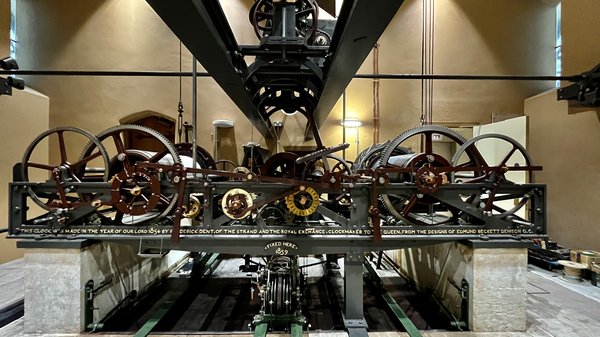

On December 31st it all comes down to a single moment, when the nation watches and waits for Big Ben to ring out and signal the start of the new year. Behind the scenes, however, months of preparation go into ensuring that this first hammer-blow falls precisely on time. Besides the installation of additional broadcast equipment, regular servicing, and thrice weekly winding there is also timekeeping: ensuring, literally, that the clock stays on time.

In the months leading up to the end of 2023, the timekeeping of the Great Clock was a core focus. After the break of six years during the servicing of the clock and tower, the twice-daily live chimes finally returned to BBC radio airwaves on November 6th. This New Year marked the 100th anniversary since the bells were first broadcast live for New Year’s Eve. It was a matter of pride that the clock should perform well and strike on time.

When it was first installed, the Great Clock was, by some margin, one of the most accurate public clocks in the world. The original specification for the clock set down in 1846 by George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, required that ‘the striking machinery be so arranged that the first blow for each hour shall be accurate to a second of time’. As clockmakers our job is to ensure that the clock remains true to this original purpose. To our advantage, we have highly accurate timekeepers to compare the Great Clock against and, armed with this information, we can regulate the pendulum carefully and actually comfortably exceed the original target for accuracy.

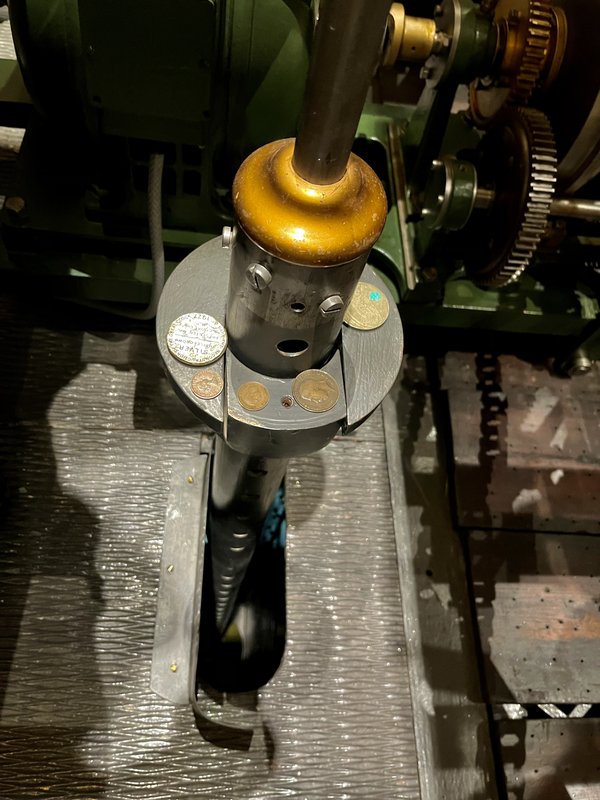

Since starting at the Palace of Westminster in August 2023, I have implemented the use of a new custom-made timer to increase the accuracy of the timing of the first hammer-blow of the hour and an improved regimen of regulating the rate of the clock’s pendulum. The core mechanics of regulation remains as ever: the placing or removing of weights, in the form of old currency, on a small platform partway down the length of the pendulum rod. Famously, one pre-decimal penny added speeds up the clock by about 2/5th of a second over 24 hours. These are a little too weighty and the adjustment too coarse if one is aiming for a finer degree of accuracy. I have begun using ha’pennies and farthings for regulation, kindly lent for the purpose by my colleague in the clock team, Ian Westworth. These speed the clock up by about a quarter of a second a day and a tenth of a second a day respectively.

In the final days running up to New Year’s Eve I was at the top of the tower, on the hour, throughout the day to take a timing reading from the strike and to make small adjustments to bring the clock precisely to time. As luck would have it, on the evening of the 30th we experienced heavy winds, which buffeted the tower and were enough to throw the clock out by 0.2 seconds by the morning of New Year’s Eve. I was able to correct for this by the evening. Midnight came and Big Ben struck, and the view of the fireworks from the top of the Elizabeth Tower was astounding. It was awesome to see the fireworks perfectly synchronised with the strike of the bell.

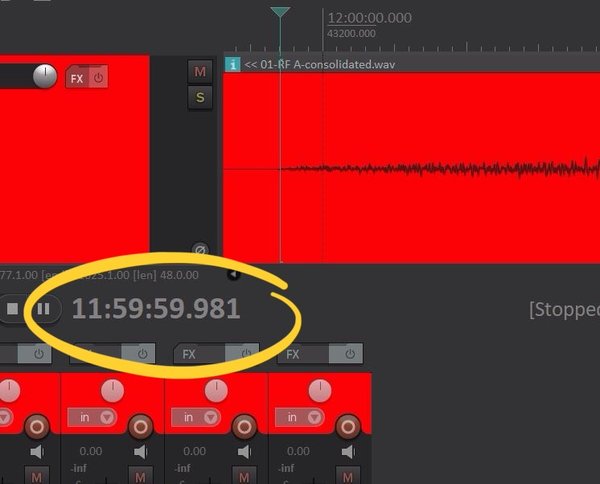

My timekeeping efforts were rewarded when we measured the timing of the strike from the sound recording compared with a GPS clock – these results were generously provided by Mark Powell of DeltaLive. The result was that Big Ben struck midnight at exactly 23:59:59.981, within less than a fiftieth of a second of midnight. That’s less than a fifth of the time it takes to blink your eyes. I must confess to being rather pleased with that!

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

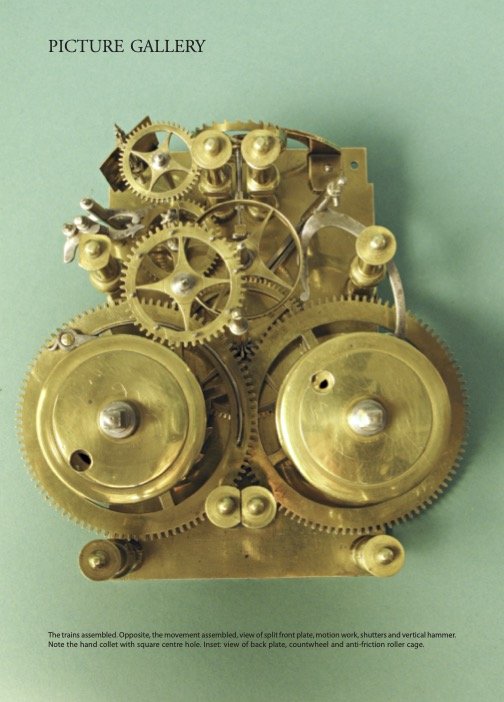

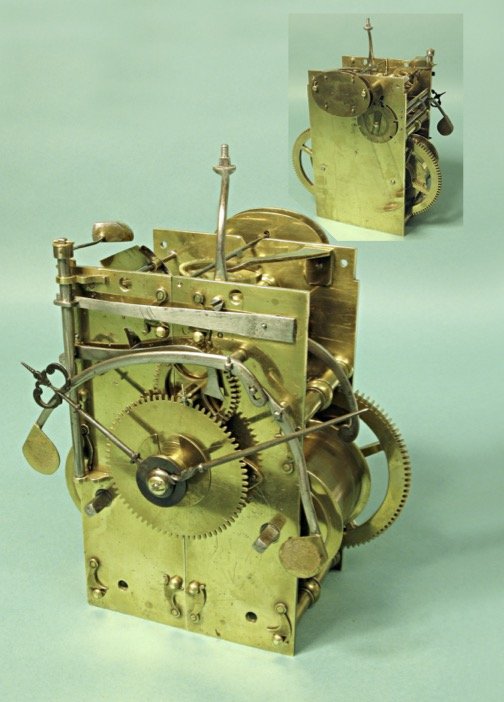

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Light among the lanterns

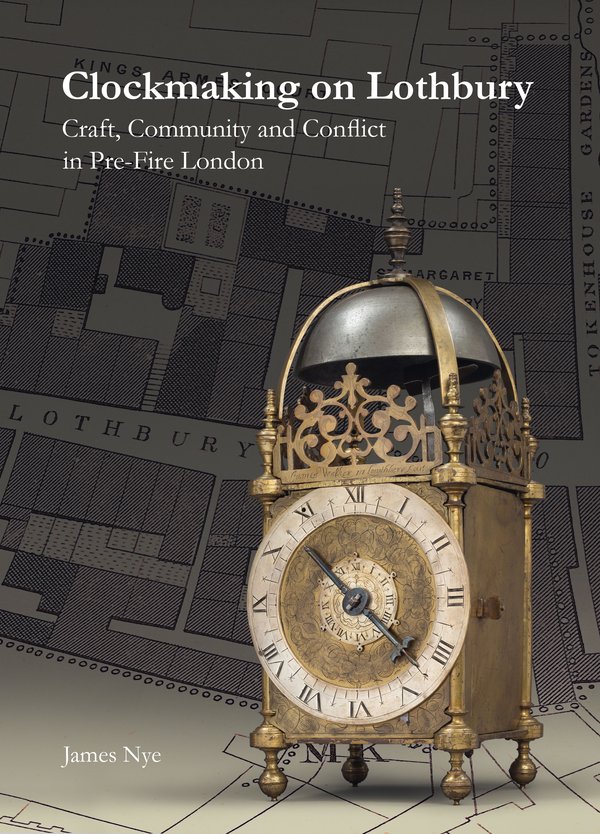

This post was written by James Nye

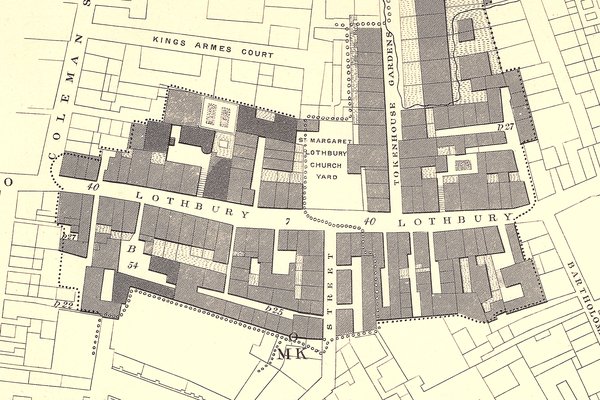

I used to walk regularly from Cannon Street tube station to the Clockmakers' Company office in Throgmorton Avenue, and on the way would walk down the west flank of the Bank of England, turn right and cross over to slip down Tokenhouse Yard. One day, passing St Margaret’s Lothbury, I stopped, and looked around. It struck me forcibly that Lothbury was really short, yet I knew that a fair number of lantern clocks were signed from addresses on the street. I was intrigued. Was this like restaurants crowding together and all benefiting from increased business?

This was back in 2018, and I conceived the idea of a deep dive into the street’s pre-Fire history. It was known for its founders, and for their ‘turning and scrating […] making a loathsome noise’. Was it such a bad place? Who else lived there, and what did they do? I recruited a research assistant, Caitlin Doherty, and together we planned trips to archives and libraries, following up hunches and leads developed together.

This all resulted in a lecture we jointly gave in November 2019, but I had to jettison more than half my material to squeeze it into a decent length. Then Covid struck and the larger work languished, until mid-2022 when I dusted it down and gave it a read. I was pleasantly reminded of much, but also conscious that a lot more could be done, so I strapped on the tanks and went overboard again.

I was still frustrated that on the first attempt I had failed to pinpoint the location of the Mermaid, the best-known Lothbury address, home to Selwood, Loomes and others, and from which the first pendulum clocks were sold in London. A punch-the-air moment occurred earlier this year when I finally found archival documents that revealed its whereabouts.

The project eventually grew to a book-length treatment and I am deeply grateful to the Society for backing its publication. It has recently been rolling through the presses. You can see pages being prepared for sewing here and the cover being embossed here.

Make no mistake, this is not a technical book about lantern clocks. But it is a forensic account of the small community in which one group of remarkable makers lived. It reveals who their neighbours were and the challenges they all faced, whether against the backdrop of the Civil Wars or the poisonous smoky atmosphere. It discusses the trades in which the merchants on the street were engaged, but reveals some of the poverty close at hand. I hope that in many ways it should throw some more light around the early life of many lantern clocks. And you can order it here!

Time's up!

This was post was written by Jonathan Betts

Have you ever had to endure a relentlessly boring after-dinner speech?

In these less-formal days there are fewer opportunities, but in the ‘good old days’ in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, when many of the elite of British society belonged to exclusive dining clubs, speeches could go on seemingly forever!

The Sette of Odd Volumes

The 'Sette of Odd Volumes', one of the more eccentric of such dining clubs, was founded in 1878 by the celebrated antiquarian bookseller, Bernard Quaritch (1819-1899). Over the following decades it was distinguished by having as members and guests many great achievers in the literary, scientific and academic worlds.

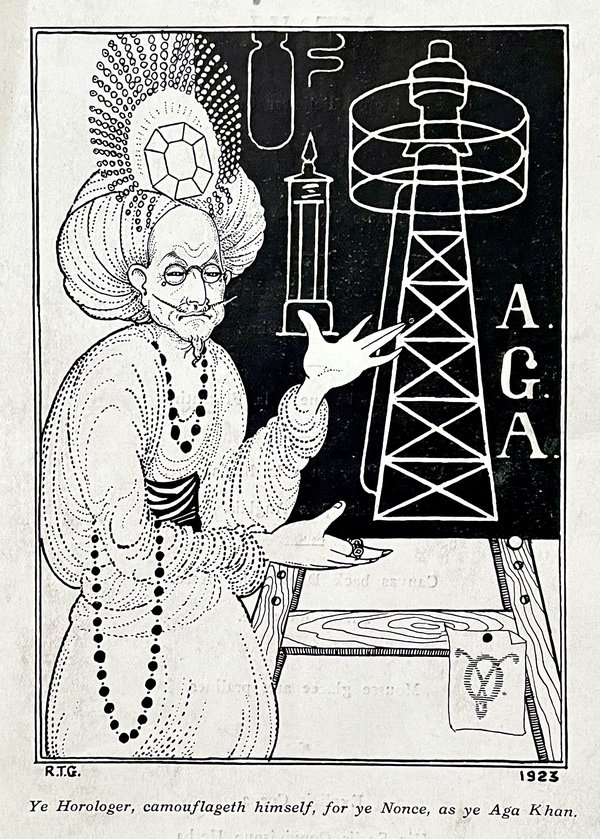

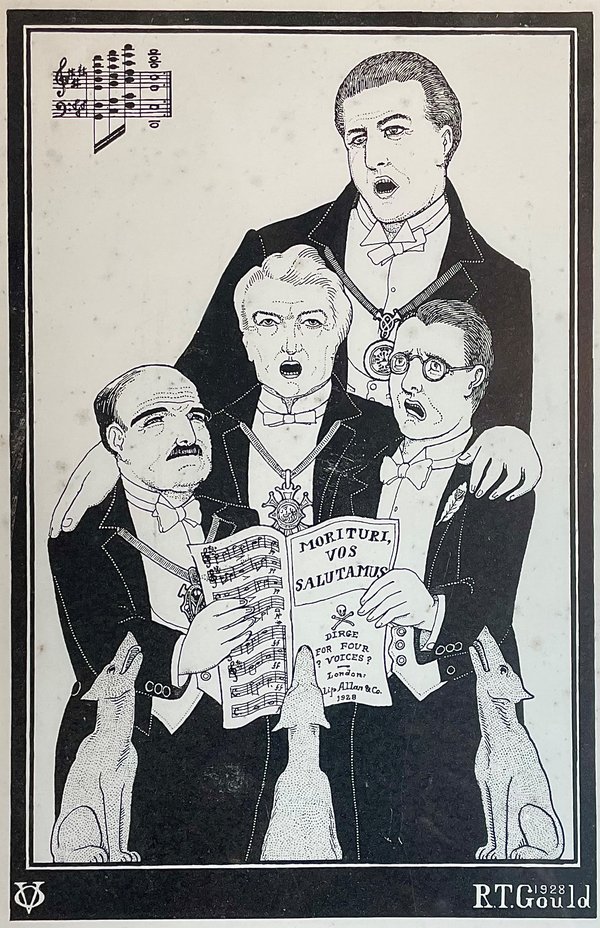

Horologically, our very own Rupert T. Gould (1890–1948) joined in 1920, and George C. Williamson (1858–1942), the antiquarian who published horology’s largest book, the catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan collection of watches, was also a member.

Members of the club were ‘brothers’ and adopted titles appropriate to their professions. Gould was ‘Hydrographer’ and Williamson was ‘Horologer’. The enforced, tongue-in-cheek jollity of the dinners required the exclusive use of their titles.

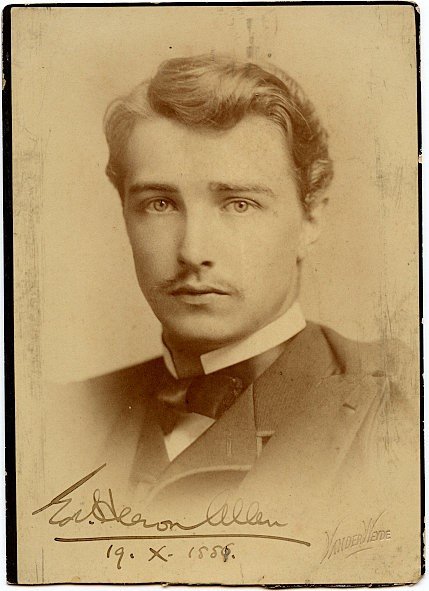

Oscar Wilde occasionally attended these Sette dinners as a guest. In later years, Wilde’s second son, Vyvyan Holland, was a Sette member, 'Idler', and was also a good friend of Gould's. Another great friend was the biologist and microscopist Edward Heron-Allen (1861–1943), ‘Necromancer’, who had joined the Sette back in 1883.

Each year, the Sette elected a new President, who sat in a grand throne-like chair when in office, and a Vice President, who would be President the following year. In 1891 Heron-Allen was about to be elected Vice President, and as a gift to the Sette (and as something of an aggrandisement to his new office!) he commissioned and presented a Vice President’s chair to accompany the President’s.

Those speeches

The Sette's activities were regulated according to a set of Rules, some of which were positively Pythonesque. For example, rule XVI was that 'There shall be no Rule XVI', and Rule XVIII insisted that 'No Odd Volume shall talk unasked on any subject he understands'.

One of the more sensible rules, however (No. XX), stated that 'No O.V.’s speech shall last longer than three minutes; if however, the inspired O.V. has any more to say, he may proceed until his voice is drowned in the general applause'.

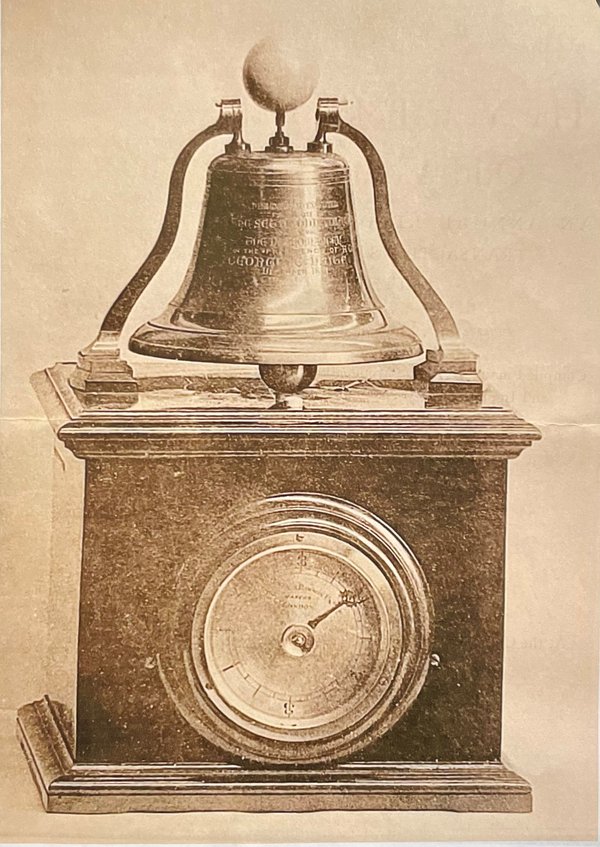

Finding that this rule was constantly being disobeyed, and that evidently the ‘general applause’ was insufficient, in December 1891 Heron-Allen also commissioned and presented to the Sette an elaborate speaker’s bell, to ensure they stuck to time.

The bell

Made by the well-known Victorian electrical engineers, Woodhouse & Rawson, the bell is of exquisite quality throughout. Constructed in a mahogany case containing the electro-mechanical timer, the large bell, mounted on the top, has a slender rod running vertically through it, which had (now missing) a ball on top.

In operation, reminiscent of the way a time ball runs, the timer is set going and the ball (which was probably an ivory billiard ball originally) is seen to slowly climb up from the bell. The ascent is controlled by a clockwork worm-and-fly governor, and at the point at which the three minutes has elapsed, the ball, now about 2.5 inches above the bell, suddenly drops back down to the bell, which then begins to ring very loudly, an electrical make-and-break hammer operating on the inside.

For the speaker, having a miniature time ball inexorably rising in front of him while he was talking must have been quite off-putting and, needless to say, the timing device was not popular. One can only imagine what Oscar Wilde would have thought (and said!) if the thing was set going as he began giving an after-dinner speech!

In fact, a certain flexibility was built into the controls of the bell, and the operator (presumably the Master of Ceremonies) was able to pause the clock, or even ring the bell in advance, if deemed necessary!

But its presence as a gift would soon be quietly but firmly removed anyway, and this fascinating and beautiful object, and the Vice President’s chair, were not seen again. This was owing to an incident which left Edward Heron-Allen unpopular among the elders of the Sette and which caused him to resign from the Sette a year or so later.

The incident, which is described in an excellent book by John Mahoney (The Richard Le Gallienne versus Edward Heron-Allen ‘Incident’ at The Sette of Odd Volumes, privately published, Tallahassee, 2023), concerned the proposal for membership of the Sette of the author and poet Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947).

Le Gallienne had had a brief affair with Oscar Wilde, and it seems that at the time he was being proposed for the Sette, Heron-Allen had made a remark in confidence at a private dinner party about Le Gallienne’s sexuality. Unfortunately, this remark was not treated in confidence, and Le Gallienne got to hear of it. This would, given the illegality of homosexuality at the time, be a very serious matter for him.

The scandal which ensued polarised views within the Sette, causing Le Gallienne’s election to be dropped temporarily and Heron-Allen to later resign. The chair and timer were thus quietly put away, though the chair does in fact remain in the Sette’s possession; the timer escaped at some stage and only resurfaced a few years ago.

For Heron-Allen the story ended happily, however. He would re-join the Sette thirty years later, and he enjoyed many a dinner with Gould, Holland and his other friends, no doubt having to put up with the long speeches after all.

Clock confusion – think about it!

This post was written by John Laycock

Why do the numbers of 1 to 12 on a clock dial have to be multiplied by 5 to allow one to work out the time?

If there are 24 hours in a day then the daily time continuum is 0 to 24. Why then do mechanical clocks split this continuum into two 12 hour segments? If the continuum has to be split surely it would make more sense to split between day and night with the daylight spanning 6am to 6pm and then night from our 6pm to 6am!

Why is noon 12pm? It is neither am nor pm - simply because we have chosen to reset the continuum at 12! Is midnight 12am? Some digital clocks will show the 60 minutes after midnight as 12.xx whilst others will show the time as 00.xx!

Several attempts have been made to design an unambiguous dial using a 24 hour clock. The modern dial below is a good example.

The most important element is the hour (long hand) with the minutes as secondary (short hand). The dial is numbered with the hours from 0 to 23, as time will be read as hour plus minute and thus 24 will never be appropriate. The shorter hand points to an inner annulus numbered 0 to 55 in steps of 5 to avoid the necessity to perform the mental x5 operation to calculate the minutes or seconds.

Why has this relatively simple and unambiguous display of time not been universally adopted? We still do not think 24 hours we think morning and afternoon.

What about the time warp that occurs when reading minutes? With the minute hand in the right half of the clock face it is usual in the English language to interpret time as 'past the hour' but when the hand moves to the left half of the clock face we usually switch dimension to 'to the next hour' e.g. twenty past six, twenty to seven.

Are we using the clock to display past time or future time? Past time is historical and cannot be used again, future time is at our disposal and should be used to best advantage. Thus the clock face should logically portray future time and not past time.

Taking into account the discussion above making the case for the 24 hour dial, should the numbering system be completely reversed. The dial should display the hours descending clockwise from 23 to 0 and similarly the minutes descending clockwise from 55 to 0 in steps of 5.

Will it happen – NO. We have two much time invested in the past!

The evils of modern living

This post was written by James Nye

If you have not seen Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits, I strongly recommend it. Without giving too much away, there are some magical (hilarious) scenes when Evil is incarcerated in the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness, planning the overthrow of the Supreme Being.

He believes he will be free, ‘Because I have understanding’. A flunkey asks, ‘Understanding of what, Master?’ Evil replies, ‘Of digital watches… and soon I shall have… understanding of video-cassette recorders, and car telephones, and when I have understanding of them… I shall have understanding of computers. And when I have understanding of computers, I shall be the Supreme Being.’

It is a 1981 film. Demanding explanations of all that is new in the world, Evil asks about fast breeder reactors. Receiving an explanation, he stares into the void. After a pause, he says, ‘Show me… Show me… Subscriber Trunk Dialling.’

For me, this was always the laugh-out-loud moment, that Evil could be so fascinated by STD.

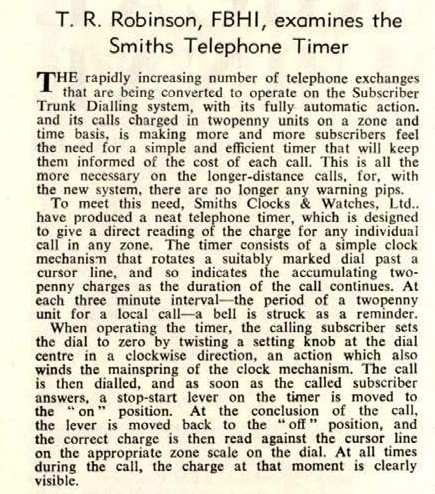

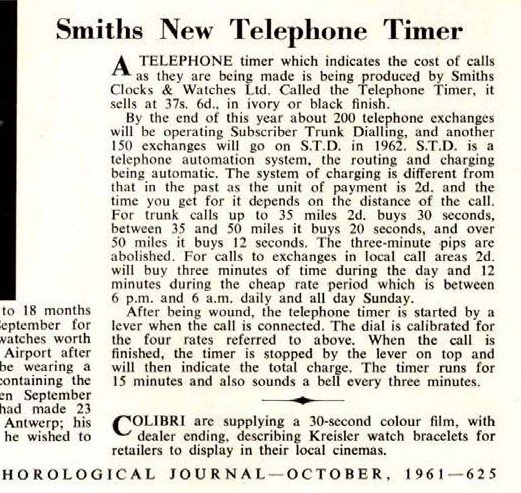

The technology had been rolled out over the previous two decades, being completed in 1979. For a long time, telephone callers had been used to fixed periods of call charging, in units costing two pence each, and would hear warning pips as each period was near to ending. STD would do away with this, and two pence would now buy different quantities on a zone and time basis.

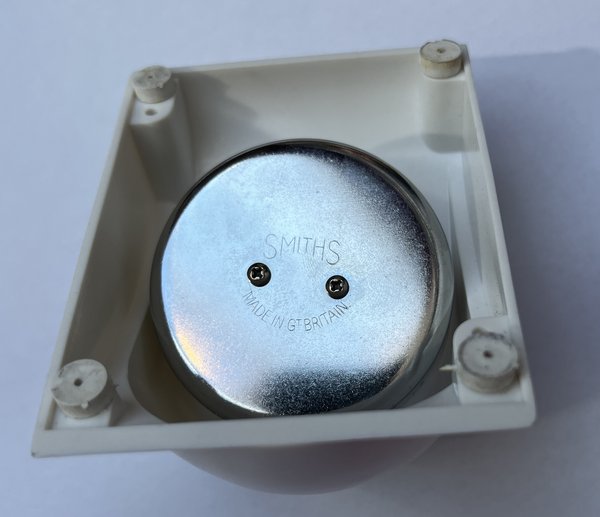

Smiths Industries anticipated a need for callers who might need reminding of the cost of their calls, and hence the Telephone Timer.

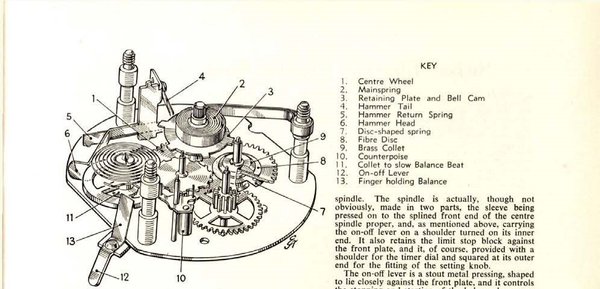

A turn clockwise of the central knob winds what is essentially an alarm-clock mechanism. The lever at the top starts and stops the clock. Once started, the dial visible through the top segment rotates anti-clockwise, and the reticle line shows call cost, based on one of four different rates.

Each two minutes, a bell is struck once, to jolt the caller back to consciousness of the pennies being frittered away in conversation.

Introduced in 1961, it was widely publicised, even meriting a full two-page review from the legendary T. R. Robinson.

Prescient as always, some of the evils Gilliam identified remain with us, while others have long since disappeared. The Smiths Telephone Timer falls very much in the latter category.

The National Physical Laboratory: paving the way for trusted time and frequency across the UK

This post was written by Leon Lobo

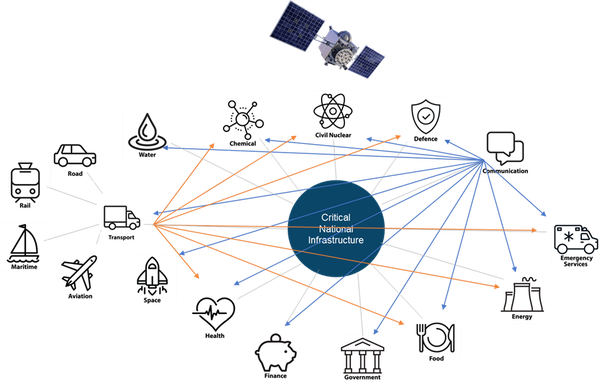

Time is the invisible utility underpinning capability across critical national infrastructure (CNI), as the basis for global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), synchronisation of 5G mobile telephone networks and the energy grid and timestamp traceability critical for trading platforms in financial services.

The world we live in is increasingly digital, with the last few years only accelerating this. We are seeing advances in communication and connectivity and society’s reliance on reliable positional, navigational, and timing (PNT) data is growing.

Many aspects of UK industry and society require increasingly precise time, whether it’s at home on our devices, the telecoms networks, energy, broadcast or in the finance industry where the time margins used are unfeasibly fine: one second for voice trading, one millisecond for electronic trading, and just 100 microseconds for high-frequency trading – all traceable to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the global time scale.

The systems, which rely on PNT signals from GNSS, are robust in themselves and have procedures in place to deal with any GNSS based system faults. However, disruptive interference can occur unintentionally and deliberately, with malicious interference a growing possibility. Potential interferences include jamming GNSS receivers, rebroadcasting a GNSS signal intentionally or accidentally, or spoofing GNSS signals to create a controllable misreporting of position.

An alternative timekeeping source is crucial to help prevent any serious impact to all of the above if something were to occur to the signals received via GNSS. They will also future proof society as we develop smart cities, autonomous vehicles and communications.

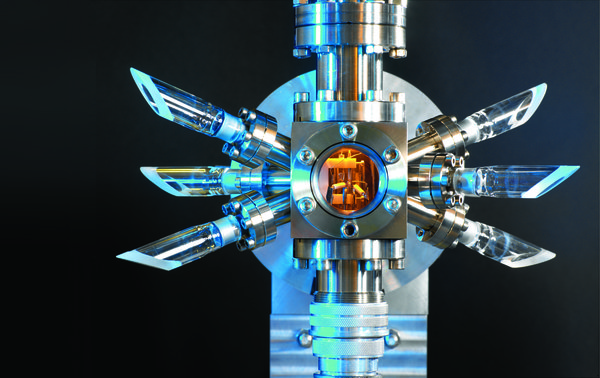

To mitigate these issues and vulnerabilities, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), through its National Timing Centre (NTC) programme, is developing an alternative, potentially primary solution for future timing. The team and I are striving to ensure that the UK digital infrastructure is supported by a GNSS-independent sovereign capability for time moving forward. I am keen that we become more aware of our dependency on GNSS and start to consider how we do things differently. Dependence by default on this space asset is no longer tenable without due consideration for resilience of operations.

The NTC programme will provide the resilience needed to protect critical national infrastructure, keeping essential services running and ensuring trust in new technologies. It will enable the UK to move away from reliance on GNSS, like GPS, for time, and leverage a range of time and frequency distribution technologies including fibre, communication satellites, and terrestrial broadcasts, alongside GNSS.

NPL’s NTC programme aims to deliver a resilient UK national time infrastructure through the building and linking of a new atomic clock network distributed geographically in secure locations. It will also provide innovation opportunities for UK companies through funding projects in partnership with Innovate UK based on a successful NPL and Innovate UK partnership model. Finally, the programme will respond to the specialist skills shortage in time and synchronisation solutions through specialist, apprentice and post graduate training opportunities.

Improved resilience will help to strengthen our society through faster, more secure internet, robust energy supplies and reliable health and emergency services. As a community that understands timing and timekeeping, I am keen to have you engaged, raising awareness of why time is important to our daily lives and what we need to consider to ensure we have resilient time for the future.

Dr Leon Lobo is Head of the National Timing Centre at the National Physical Laborartory, whose work focuses on developing and delivering the UK's national timing strategy. Having worked at NPL since 2011, Dr Lobo has led the team managing the UK’s time scale and supported on the development of NPLTime®

The perils of poor lubrication and a potential solution

This post was written by JC Li

We all know the perils of poor lubrication: creeping oil, deterioration, wear… the list goes on. Good lubrication is paramount to the correct functioning and prevention of wear for horological mechanisms. Although modern synthetic oils have come on in leaps and bounds from the old-school vegetable oils and refined whale blubber, it can still prove challenging to ensure that they don’t ‘creep’ away from friction points to other areas. Where there is friction without oil there is wear, which can impede functionality and result in irreversible loss of material.

One solution used by some watchmakers is to apply a thin oleophobic (oil-repelling) coating known as epilame which helps retain oil at critical points, particularly in the escapement. However, it does not appear to be used as commonly by clock makers and repairers, typically oiling their escapements in the traditional way with no surface coating. As The Practical Lubrication of Watches and Clocks by the British Horological Institute (2008, p.15) states:

'Surface treatment to prevent spread of oils is not commonly used in clocks but can have similar advantages to its use in watches.'

As an MA Horology student at West Dean College, I’m hoping to establish through my thesis whether the use of modern epilame products such as Moebius Fixodrop or Episurf-Neo could be a conservation-grade solution to oil creep on pendulum escapements.

As such, it would be of great help to me if readers could respond to my two-minute survey about this topic, both in order for me to gauge current practices and also receive some feedback on this research. I equally welcome any pointers in this area of study or any relevant anecdotes of personal experience about oiling escapements, epilame, or any of the other issues referred to. I can also be contacted using my West Dean email address: s21jl@westdean.ac.uk. Thank you.

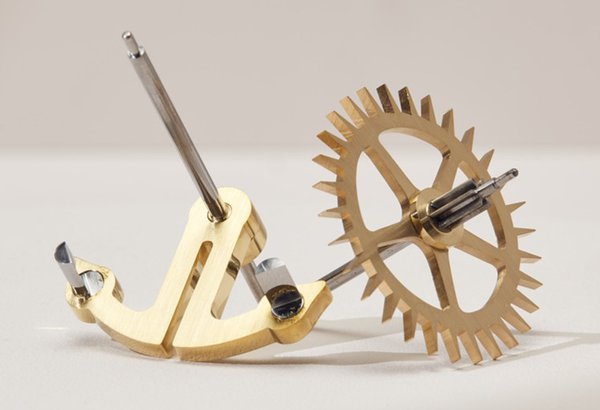

An animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement

This post was written by Eliott Colinge

Visual representation has always been a core means to learn about horology and explore its principles.

The literature provides countless invaluable schematics about escapements, repeating mechanisms and patents of all sorts. Less can be said about video representations. If an image is worth 1000 words, what can be said about a video?

The recent popularisation of 3D animation in the film and gaming industry has gathered a wide community of brilliant individuals giving their improvements to the field at an increasing pace.

It is hardly possible to have a conversation about 3D animation without hearing the word 'Blender'. Being open source, the software has attracted students, researchers, professionals and amateurs around the world and is increasingly becoming a standard in the industry. Blender is such an incredible playground and I am always in admiration of what gets produced by the community.

As a trained conservator of horological artifacts, I founded the animation studio 'Vecthor' to provide complementary 'non-interventive' solutions to help education around collections.

Vecthor has made available a series of short animations of escapements based on drawings and a YouTube video about Pierre Leroy’s marine watch (available in English and French).

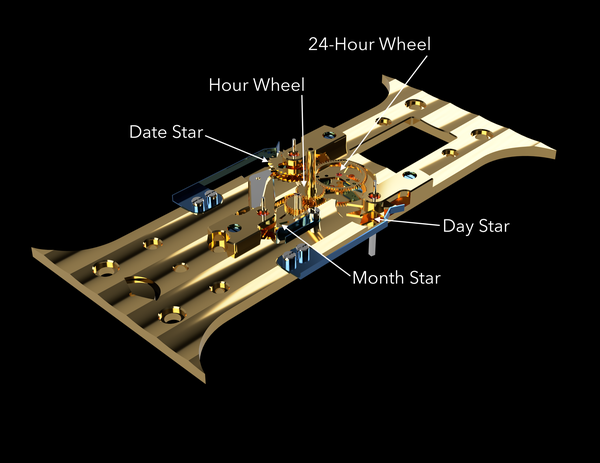

Here is an example through an animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement used in his marine chronometers during the 1770s. The impulse energy is stored in the coiled springs (constant-force) and transmitted to the balance during its oscillatory arc.

Other escapement animations can be found on Vecthor's instagram: @vecthor_animation

A sad commemoration

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A couple of weeks ago, I attended Bob Frishman's NAWCC conference on 'Great Horological Collectors' at the Horological Society of New York's home in New York City – a wonderfully successful and interesting event. By good fortune the date of the conference came just before a short holiday we had planned in New York, with passage home on the Queen Mary 2 – a delightful way to cross the pond.

When planning the trip I realised that, by a rather extraordinary coincidence, during the transatlantic crossing there would occur the 80th anniversary of a family tragedy, played out in those very waters.

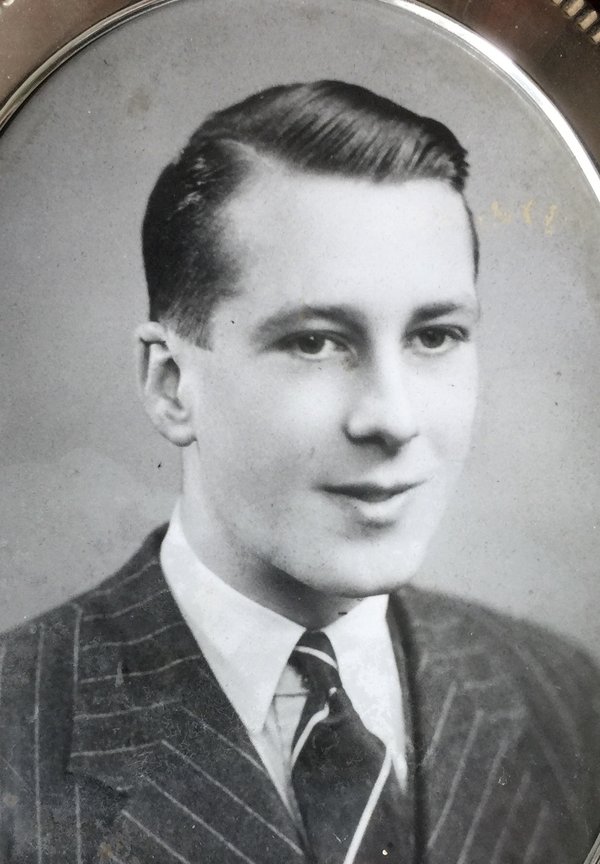

My Uncle Pat – my mother's brother – was serving on a merchant troop ship, the MV Abosso. On the evening of 29 October 1942, when the ship was travelling alone in the North Atlantic, it was torpedoed by a U-boat and sunk. 362 of the 393 passengers and crew lost their lives, including Uncle Pat, who was just 23 and had married only a few weeks before.

Just one lifeboat survived with 31 souls to tell the tale, some of them Navy officers who were aware of the detail of what happened.

The reason for telling this sad tale in an AHS blog is that there were two critical horological elements to the tragedy.

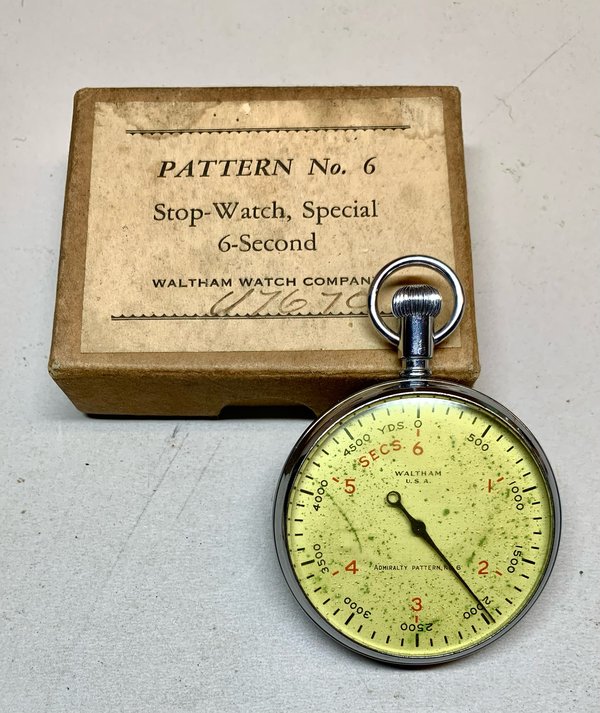

About 6 p.m. that evening, the master of Abosso, Captain Reginald Tate, became aware the ship was being tailed by a U-boat – U575, commanded by Kapitan-Leutnant Gunter Heydemann (1914–1986), as it turned out. The ship's crew was able to detect the submarine using ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) echo-sounding to determine the sub's bearing and distance, the latter by using an ASDIC chronograph.

The watch has a high frequency sweep-seconds hand on a dial recording up to six seconds, the time between transmission of the sound pulse and the echo determining the distance of the sub from the ship.

Having established precisely where the sub was, the ship's master had to decide what to do.

An option was to go full steam ahead and try to out-run the submarine, which would normally be possible – a submerged submarine makes much slower progress, though at a maximum speed of 14.5 knots, the Abosso was not a particularly fast ship.

The alternative was to adopt a 'random' zig-zag course so the U-boat could not predict the ship's position accurately enough to make it worth firing torpedoes at it, though zig-zagging naturally slowed down the progress of the ship considerably. The practice did generally work well, if maintained long enough, as U-boats had limited quantities of fuel and eventually had to head off for a rendezvous for refuelling.

Deciding not to try and out-run, but to zig-zag, the Abosso brought into action its zig-zag clock, a part of the navigational equipment on the bridge of WW2 merchant ships at the time.

A fairly standard ship's bulkhead clock is adapted to have an electrical contact at the tip of the minute hand, and round the periphery of the minute track on the dial is a metal ring with a number of moveable electrical contacts.

Each time the minute hand touches a contact it closes a circuit and a bell rings in the wheelhouse informing the crew to change course one way or the other.

If in convoy with other ships it is of course vital that all the ships adopt precisely the same agreed pattern of zig-zags, and when the instruction to zig-zag is given, the whole convoy would be signalled a secret code for the pattern to be used. The contacts on all the ships’ clocks would then be adjusted accordingly and zig-zagging would begin at a specific time, thus foiling the U-boats' attempts to align torpedoes with a target ship.

The log of U575 has survived, so we can also follow what happened from the U-boat’s perspective. Heydemann, a much decorated Commander in the ‘Brandenburg’ wolfpack in the North Atlantic, sighted the Abosso about 6 p.m. that evening. He was running low on fuel but decided to try and attack. Realising he was being traced, he went deep, out of reach of the ASDIC, but followed from a distance until he was nearly out of fuel. At that point, thinking they had lost the sub, Abosso’s master made the fatal decision to stop zig-zagging. Realising this, Heydemann risked running out of fuel and moved closer to the ship to attack.

Reading the U-boat's log today, and comparing with the U-Boat Commander’s Handbook (available as a translated reprint as E. J. Coates (translator), The U-Boat Commander’s Handbook, Thomas Publications, Gettysburg, 1989) one discovers this was a textbook operation.

At 22.13hrs, Berlin time, one of the middle torpedos of four directed at the Abosso in a fan pattern struck the ship virtually amidships. The U-boat surfaced to inspect the target and Heydemann recorded seeing lifeboats being launched. One more torpedo was fired into the ship to deliver the coup de grace, and about half an hour later Abosso sank, U575 then departing to rendezvous for refuelling.

The one lifeboat which survived was picked up on 31 October by HMS Bideford, one of a convoy forming part of 'Operation Torch', heading for North Africa but, in the heavy seas at the time, no other lifeboats or survivors were ever found.

On the evening of 29 October this year, exactly 80 years later, and as close to the location of the Abosso’s sinking as I could estimate, I sneaked a centrepiece flower arrangement from our table after dinner and, against Cunard’s strictest rules, cast them into the sea at the stern of the ship.

A timekeeper had shown Abosso where the danger was, and the other timekeeper should have saved them. It is a sad thought that if only Captain Tate had left his zig-zag clock running just a little longer, the U-boat would have had to leave and 362 lives would not have been lost.

R.I.P. Uncle Pat.

Clocks in Lisbon

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Any horologist visiting Lisbon will want to visit the Casa-Museu Medeiros e Almeida, situated just off the majestic Avenida de Liberdade: https://www.casa-museumedeirosealmeida.pt/

It is the house where the Portuguese businessman António Medeiros e Almeida (1895–1986) lived and which he filled with his private collection of objects of decorative arts, including a collection of clocks and watches. It opened as a museum in 2001.

As explained in the catalogue, which I reviewed in Antiquarian Horology in December 2019, it 'consists of a core of about 650 items. [...] The timepieces cover a period of five centuries and are from France, England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Portugal, Russia, China and Japan'. A special gallery was created for them, but clocks are also found in many other rooms.

However, I want to direct you to two other clocks elsewhere in the city.

The first is in the Military Museum, a distinctly old-fashioned – but to me rather inspiring – place; some photos can be found on http://www.exercito.pt/pt/quem-somos/organizacao/ceme/vceme/dhcm/lisboa. On display in one of its enormous rooms is a turret clock with a plaque explaining (I translate from the Portuguese):

'Constructed in Lisbon in the 18th century by the clockmaker F. Baerlein, it was the only turret clock in the neighbourhoods of Santa Apolonia, Santa Clara, Alfama, and surroundings. It commanded all the clocks in the various establishments of the Royal Armoury of the Army, and also serving the population of the nearby areas as well as the crews on the ships on the river Tagus. After being struck by a grenade in May 1915, it stopped functioning. It was repaired in March 1957 […], which the staff of the Military Museum have marked with this plaque.'

A web search found nothing on the maker. What I did find was a photo of the base of a lamp post in Lisbon with the name F. BAERLEIN. Clearly later than the clock movement, but then, perhaps Baerlein had successors in the city?

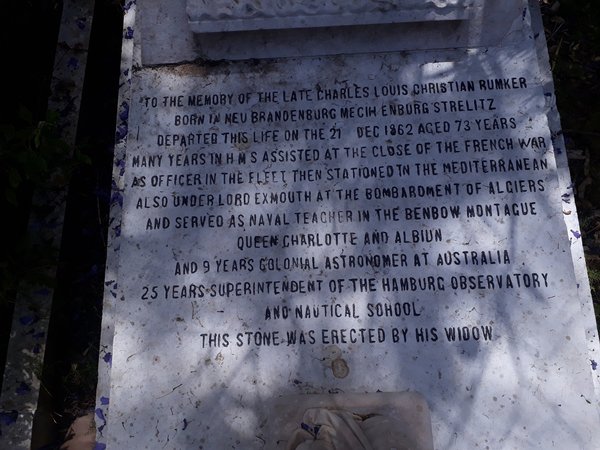

For the second clock, one must enter the beautiful British Cemetery https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/ located opposite the Estrela Park. Tourist guides invariably single out the memorial to the author Henry Fielding (1707–1754), best known for his novel Tom Jones. But to me of far greater interest is the memorial erected for the German-born Charles Louis Christian Rümker (1788–1862) https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/interesting-monuments which was the subject of an article by Julian Holland in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society No. 77 (2003), pp. 32-35.

Rümker served as colonial astronomer in Australia and later as superintendent of the Hamburg Observatory and Nautical School, and the monument shows the tools of the astronomer, including a clock.

While funerary monuments often show an hour glass, symbol of the passing of time, the representation of a clock is certainly rare, perhaps even unique? I would be interested if anyone knows other examples.

The humpback carriage clock

This post was written by William Oke

I have just finished studying on the Horology undergraduate course at Birmingham City University. For my final project, I built a humpback carriage clock and this project allowed me to research surviving examples of these to inform the design, gathering as much information as I could to create a record of those clocks. These are some of my findings.

Abraham Louis Breguet and his son, Antoine-Louis, produced many fine travel clocks including the silver-cased ‘pendule portiques’ that were sold between 1812 and 1830 [1]. Features that are included in nearly all humpback carriage clocks can be traced back to these, including silver engine-turned dials, Breguet’s iconic hand style and a number of complications necessary for travelling such as alarm, calendar work, and moonphase for travelling at night. I have been able to find records of eight of these in various collections.

There are also contemporary examples by the brothers James Ferguson Cole and Thomas Cole. During his life, Cole was called the 'second Breguet' [2]; he made several complex humpback carriage clocks with retrograde astronomical work; the earliest example is from the year of Abraham Louis Breguet's death, 1823 [3]. There is a detailed description of this clock in the first volume of the Horological Journal from the time, which also states seven more were made in the subsequent 30 years [4].

The English tradition of producing these clocks was continued by the London clockmaking firm Jump. The earliest example I have been able to find was sold by Ben Wright, hallmaked 1878 [5]. This clock was made for Francis Baring, 1st Baron Revelstoke, and three further humpback clocks were ordered from Jump by the Baring Bank partners Barons Northbrook, Ashburton and Cromer.

Until this Revelstoke example appeared on the market, the only other of these four whose whereabouts was known was the one made for Ashburton, which came up for sale at Sothebys in 1998. Interestingly, the Ashburton clock was described in a letter to Colonel R. Quill from A. Hayton Jump (great-grandson of the company's founder, R. Jump), who designed 'the last dozen' of these Jump humpback carriage clocks:

“the first of these clocks was made for a Lord Ashburton of the Victorian period before I was in the business. It cost the firm a load of money in time and trouble, for so many men had to make so many parts (the man that made the hands couldn’t do anything else, etc. etc.). My father presented the bill to Lord A with trembling hands and apologised for the high charge. Lord A took the bill and wrote out a cheque at once for double the amount charged on the bill!!! And expressed his appreciation.” [6].

The most recent examples of humpback carriage clocks were produced in the mid-20th century, firstly by Philip Thornton who made several in the immediate postwar years including one that was commissioned by Charles Frodsham & Co. to be presented to Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (who was also in possession of the Breguet pendule portique, No. 2806) [7]. It is likely the last humpback carriage clock was made by Quill and J.S Godman in 1963, which was based on the clocks by Thornton.

These historic examples are rare but have been seen to come up for sale fairly regularly; there is no doubt that their pleasing design and the fine craft skill they display leave them as popular today as when they were first made.

Footnotes:

- Daniels, G., 1975. The Art of Breguet. 2021 ed. London: Philip Wilson Publishers, pp. 78-79.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, p. 112.

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd.

- The British Horological Institute, 1859. Horological Journal, 1, pp. 134-135.

- Ben Wright Clocks Ltd, 2016. Jump, London. https://www.benwrightclocks.co.uk/clock.php?i=105 [Accessed 3 May 2021].

- Allix, C. & Bonnert, P., 1974. Carriage Clocks, Their History and Development. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club Ltd, pp. 289-90.

- The Royal Collection Trust, n.d. Carriage clock 1947. https://www.rct.uk/collection/2943/carriage-clock [Accessed 18 April 2022].

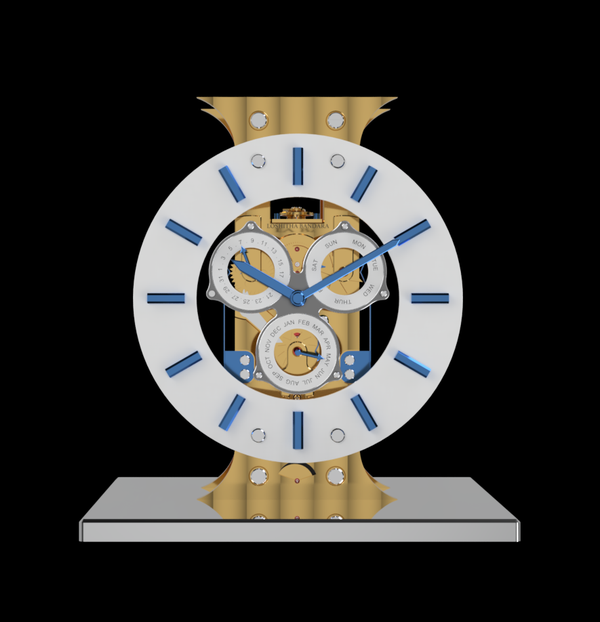

The AHS Birmingham City University Prize 2022

This post was written by James Nye

At the Birmingham City University School of Horology awards evening on 16 June, the AHS BCU Prize was awarded to Loshitha Bandara for his outstanding final-year project, a skeletonised mantel clock with triple calendar and power reserve indication, inspired by F-P Journe and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Many congratulations from the AHS! Winning this award with such an accomplished clock is a clear signal that we should watch out for Loshitha who no doubt has an amazing career ahead of him.

The clock is a tour de force, involving a range of finishes including engine-turning, Geneva stripes, perlage, straight-graining and guilloche.

The Ivanhoe Astrolabe

This post was written by Andrew Miller

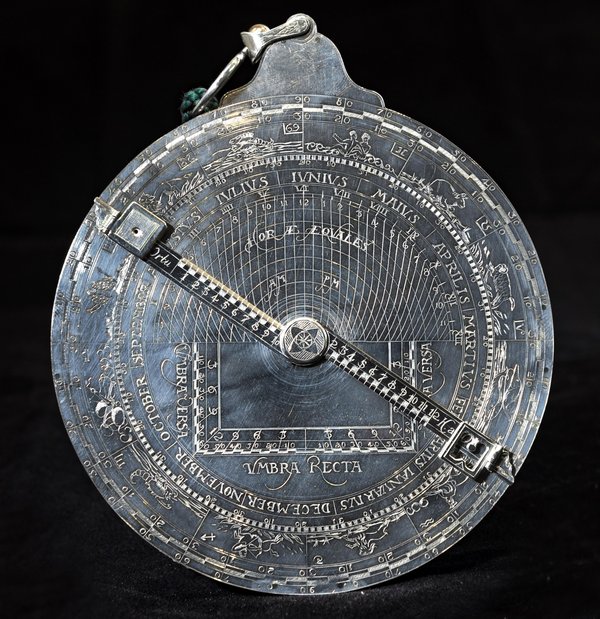

Recently I re-discovered (in a drawer) a piece of work that for me is ancient (30 years) but for the type of work is quite new (less than 500 years). It might be of passing interest to members.

It is solid state and largely untroubled by mechanical disturbances. Its accuracy should not deteriorate significantly over the next few hundred years.

It is a 1988 reworking to a smaller scale of an Arsenius astrolabe. Arsenius worked in Holland in the 16th century and is one of the great astrolabe makers. The original would have been a brass instrument some 11" diameter; this is 110mm and made of silver, ebony and copper.

The era has been updated to the current era, whereas many astrolabes are calibrated for an era some 2000 years ago when the fixed stars and constellations were first placed around the ecliptic. This is handy for using the instrument today although astrologers prefer the ancient calibration because the stars are in the 'right' place relative to Sun and planets.

The device was the must-have techno-gadget for cool dudes in the late 1500s. It will show current time and date if you have celestial sightings and the positions of the fixed stars and Sun if you have a time and date.

It will calculate not only the equal and unequal hours (the latter used in medieval times before reliable clocks were widely available) but also the height of tall buildings.

The face of the instrument has the standard rete (web) and rule through which the latitude plate can be observed. Four latitude plates are included inside the instrument and are engraved for five northern latitudes. The reverse has the calendar and zodiac on a 360 degree scale which can be used with the alidade for sighting the altitude of the Sun and fixed stars as well as predicting their altitudes.

Made in 1988 after I had spent some months at sea on the sailing yacht 'Ivanhoe' and had ample time to star-gaze under unpolluted skies. So I call it the Ivanhoe Astrolabe.

Inspiring people with horological collections: a guide’s perspective

This post was written by Robert Lamb

Since October 2015, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection of clocks, watches and associated objects has been displayed in its new home at the Science Museum, where it is accessible to the public whenever the Museum is open.

I have been conducting 60-minute tours of this wonderful historic collection on a monthly basis since July 2019. Despite needing to pause during the pandemic when the museum was closed, myself and the other volunteer guides have been back up-and-running since October 2021 and we hope that the frequency of the tours will increase as more volunteers join the team.

So, what happens on my tours?

Firstly, I introduce myself to the group and enquire if anyone has any specific interests. Participants are a pretty eclectic mix of those who, by chance, saw the notice at reception, those who came especially to see the collection, inquisitive tourists, and passers-by who show an interest and I cajole to join!

I then explain that we will not cover the whole collection, but will be honing-in on specific objects and groupings or significant topics and people.

I always like to give a short introduction to cover the origins of the collections, history of clockmaking and development of London’s Livery Companies.

Having gauged the mood and interest of the group (not forgetting that children may need entertaining too!), we often start with the introduction of domestic clocks in Europe and London, followed by the later need for more accurate timekeeping. Often, we look at the introduction of the pendulum and I talk about the development of clocks in London with the knowledge brought back by John Fromanteel. We are regularly drawn to John Harrison and his fight for recognition to win the Longitude Prize and then become fixated by H5!

There are so many tales to tell of the many objects we encounter. I love the one of an early Master of the Company, whose role was to keep the Company chest (which contained the silver and significant documents) at home during his tenure, but couldn’t get it through his front door!

No two tours are ever the same, which gives me great pleasure and I hope it does this for the participants.

Joining a tour is the only way to see what actually happens – visit the fabulous collection yourself and soak up the wonders of such a diverse horological history!

A curious dial in a south-London cinema

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

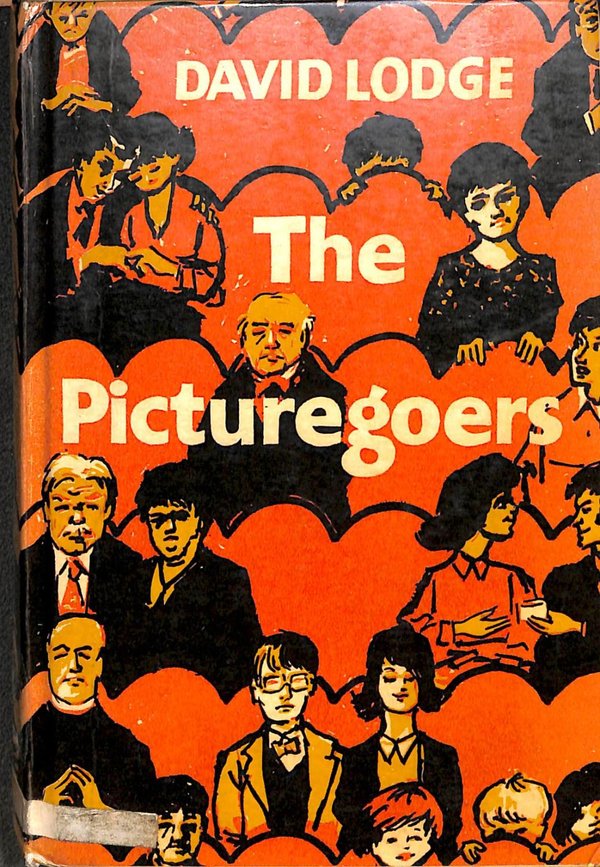

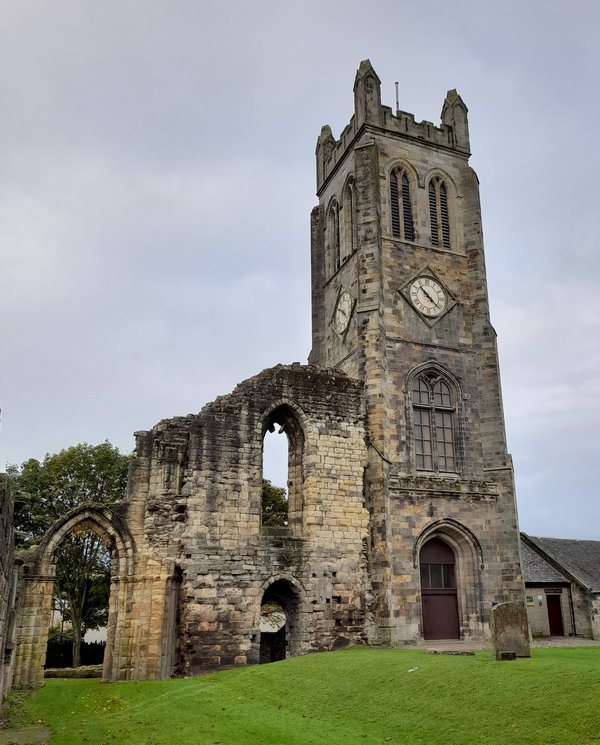

In a blog 'Letters on the Dial', posted 8 November 2012, I drew attention to dials that instead of hour numerals have letters. These can range from the name of the owner – I showed watch dials with the names Thomas Stevens, George Catling and James Catling – to a biblical quote, as seen on the dial illustrated on the cover of a journal issue.

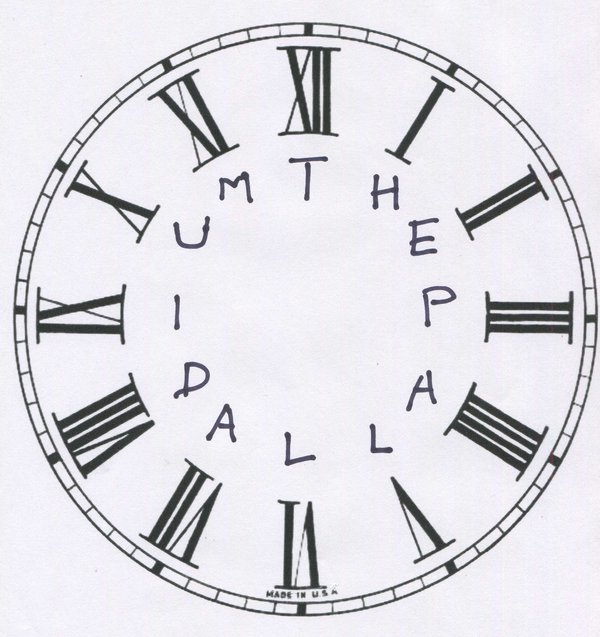

A while ago I read the first novel of the novelist and literary critic David Lodge (born 1935) called The Picturegoers, originally published in 1960. The story is set in a London suburb called ‘Brickley’, which closely resembles Brockley and New Cross in south London where Lodge grew up. It depicts the lives of a number of people of varying ages and social backgrounds who live there and go to the same local cinema, called the Palladium, on Saturday evenings.

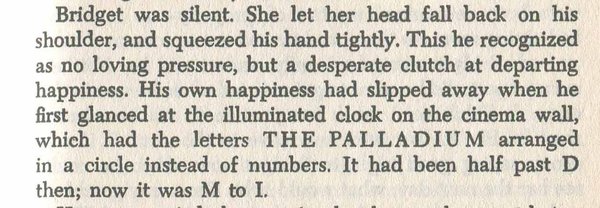

One of the characters is a young lad who takes his girl to the cinema but can hardly enjoy it as he is fretting about whether he will be on time to walk her home before his own bus, the last of the evening, leaves. 'His own happiness had slipped away when he first glanced at the illuminated clock on the cinema wall, which had the letters THE PALLADIUM arranged in a circle instead of numbers. It had been half past D then; now it was M to I'.

There was a picture theatre in Brockley named Palladium Cinema from 1915 to 1929 and New Palladium Cinema from 1936 to 1942. It was then renamed Ritz, closed in 1956 and demolished in 1960. (http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/27905). It is tempting to think that the young Lodge saw the dial there – surely he wouldn’t have made this up? I have written to the publishers of my edition of Picturegoers, Vintage, asking them to forward my question to the author, but to date have not heard back. One wonders whether others old enough to have visited the Ritz recall seeing the dial?

.

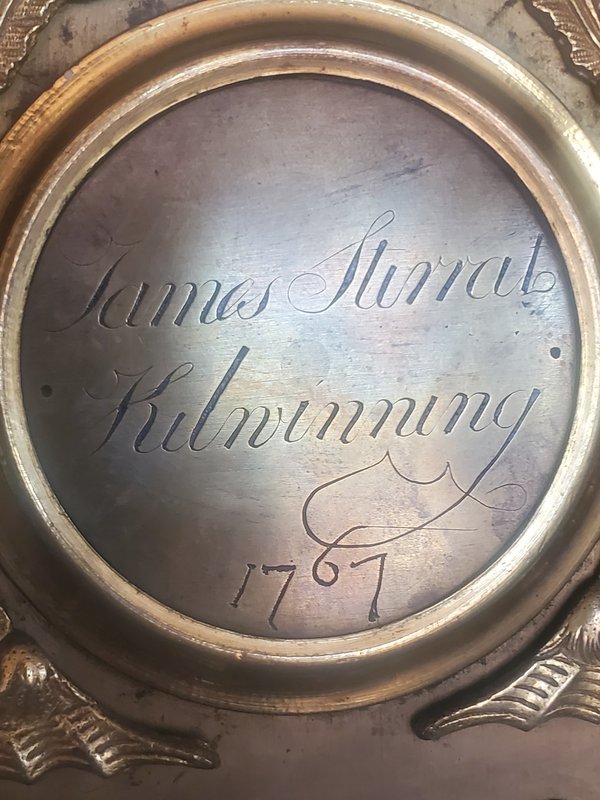

The clock and watchmakers of Kilwinning

This post was written by Heather Upfield

Kilwinning is a little town in south-west Scotland, which grew around the twelfth century Abbey (now in ruins). Following the collapse of the one remaining medieval tower in 1814, a new Abbey tower was built in 1816. James Blair, Kilwinning clockmaker, was commissioned to make the turret clock. As an interested local resident, I undertook research into James Blair for Kilwinning Heritage, in 2019.

The project grew exponentially, with a study of Whyte’s (1) compendium of around 8,000 people involved in clockmaking in Scotland. I discovered that James Blair was not the only Kilwinning clockmaker. There were eight men providing an almost unbroken stream of clockmakers in Kilwinning, from the mid-eighteenth century into the early twentieth:

James Stirrat longcase (1767-1790); James Blair longcase and turret (c1802-1836); David Loudon (c1836-c1850); William Allan longcase (c1816-1850); Hugh Millar longcase and turret (?-1860); James Gibson longcase (1867-1882)(2); Andrew Johnstone watches (1870-1893); and William Torry longcase (c1882-c1911). Years given are dates of trading in Kilwinning.

What makes this so significant for Kilwinning’s history is the fact that while much is known of the local large-scale industry (mining, brickmaking, the ironworks), clockmaking was a hitherto unknown and undocumented industry and trade, taking place at street level. It produced a seemingly extraordinary number of clockmakers for such a small town (population 1,934 in 1820). All of this information, plus the three Kilwinning turret clocks, was published by Kilwinning Heritage as Time Piece (3) in 2019.

Following publication, we have been contacted by several people from Scotland, England, and as far away as Vancouver, Canada, and Nevada, USA, all of whom, miraculously, own Kilwinning-made longcase clocks. We would be delighted to know if there are any other Kilwinning-made clocks and watches out there. If you have one in your possession, or know of others, then please contact Kilwinning Heritage at kh2011@hotmail.co.uk. We look forward to hearing from you!

References

- Whyte, Donald (2005). Clockmakers and Watchmakers of Scotland, Mayfield Books, Ashbourne, Derbyshire

- James Gibson closing shop and William Torry taking over, Ardrossan & Saltcoats Herald, 15 July 1882. www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000962/18820715/025/0001. Accessed 7 August 2019

- Upfield, Heather (2019). Time Piece: a history of James Blair and the Clocks, Clock & Watchmakers of Kilwinning 1719-2019, Kilwinning Heritage, Kilwinning www.kilwinningheritage.org.uk

Photography

Abbey Tower and James Blair turret clock: Heather Upfield

All other photographs: Current clock owners. Reproduced with kind permission

A prize-winning project 2021

This post was written by Iolanda Clopotel

My name is Iolanda Clopotel, and I have recently completed my degree in Horology studied at BCU in the School of Jewellery.

Our last and major task within the course was designing and manufacturing, from stock, a clock of our own design. This project allowed us to explore and put in practice the knowledge and skills learned in the previous years, and I have chosen to make a clock inspired by the French drum movements, featuring a Brocot escapement.

Learning more about the design of this escapement was a wonderful experience, and I am happy to have succeeded in making a working escapement by the end of the course, both in reality and in the virtual environment.

I was lucky enough to achieve the highest scoring marks in my year group and I would like to thank LVMH Watches and Jewellery for the wonderful prize in the form of a beautiful chronograph that I will wear with pride from now on, as a reminder of my own achievements.

I would also like to thank the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers for their award which will be very useful in completing future and on-going projects.

I feel grateful for the people and companies that support and reward new horologists that are just entering the field and help in keeping the passion for always improving the craft skills of precise timekeeping.