Time's up!

This was post was written by Jonathan Betts

Have you ever had to endure a relentlessly boring after-dinner speech?

In these less-formal days there are fewer opportunities, but in the ‘good old days’ in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, when many of the elite of British society belonged to exclusive dining clubs, speeches could go on seemingly forever!

The Sette of Odd Volumes

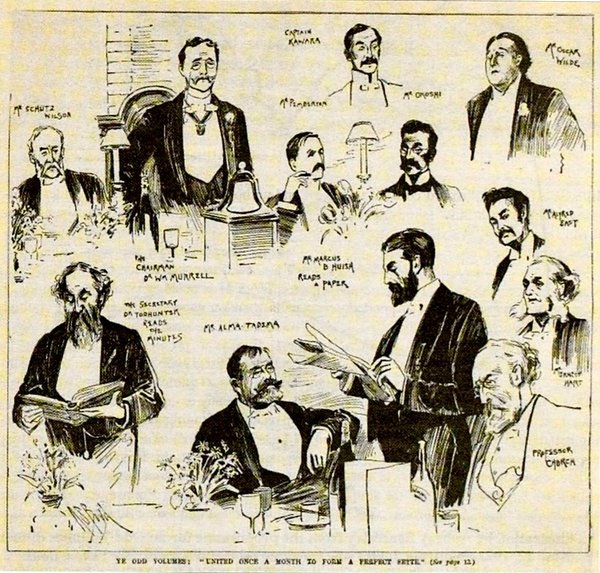

The 'Sette of Odd Volumes', one of the more eccentric of such dining clubs, was founded in 1878 by the celebrated antiquarian bookseller, Bernard Quaritch (1819-1899). Over the following decades it was distinguished by having as members and guests many great achievers in the literary, scientific and academic worlds.

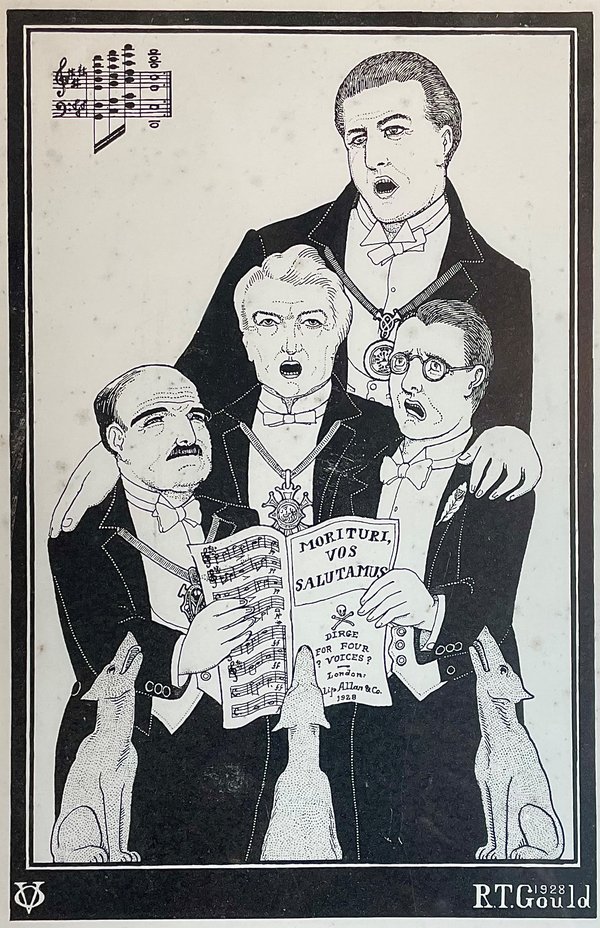

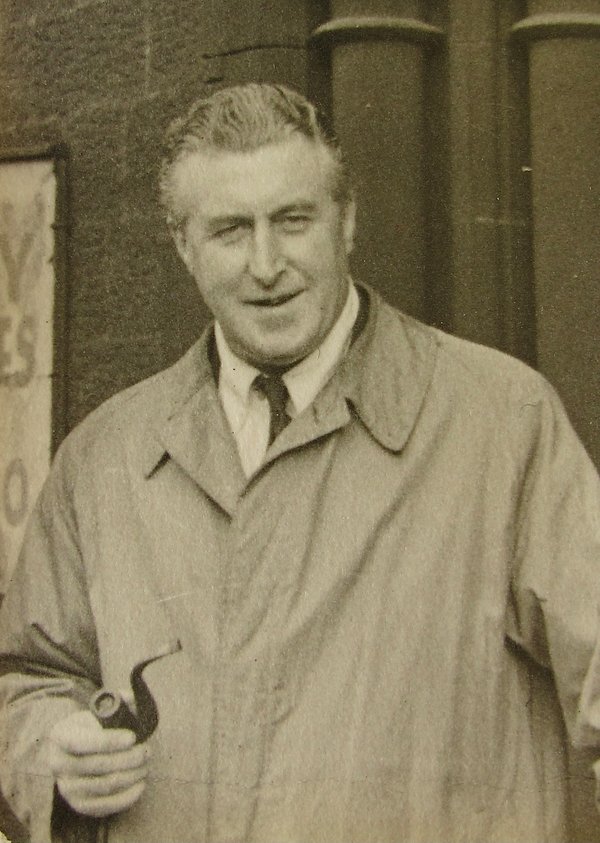

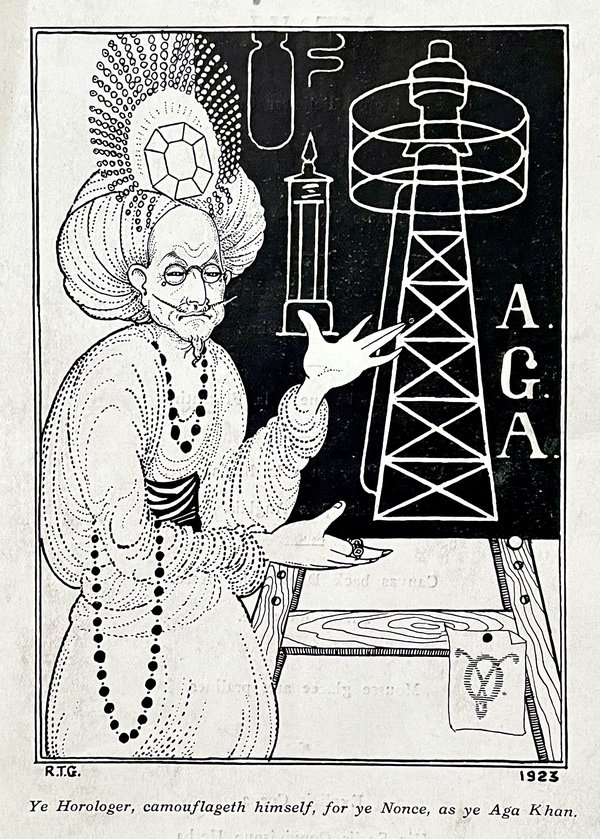

Horologically, our very own Rupert T. Gould (1890–1948) joined in 1920, and George C. Williamson (1858–1942), the antiquarian who published horology’s largest book, the catalogue of the Pierpont Morgan collection of watches, was also a member.

Members of the club were ‘brothers’ and adopted titles appropriate to their professions. Gould was ‘Hydrographer’ and Williamson was ‘Horologer’. The enforced, tongue-in-cheek jollity of the dinners required the exclusive use of their titles.

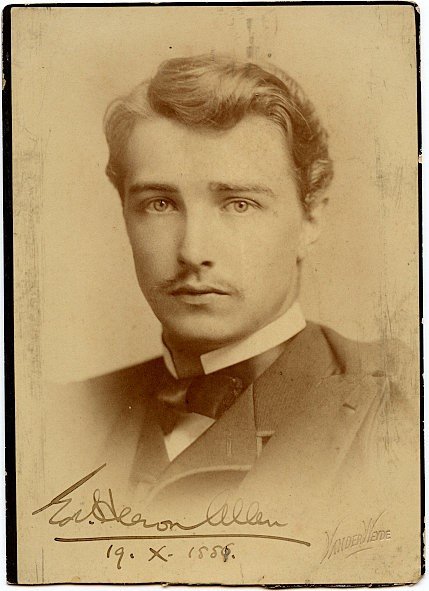

Oscar Wilde occasionally attended these Sette dinners as a guest. In later years, Wilde’s second son, Vyvyan Holland, was a Sette member, 'Idler', and was also a good friend of Gould's. Another great friend was the biologist and microscopist Edward Heron-Allen (1861–1943), ‘Necromancer’, who had joined the Sette back in 1883.

Each year, the Sette elected a new President, who sat in a grand throne-like chair when in office, and a Vice President, who would be President the following year. In 1891 Heron-Allen was about to be elected Vice President, and as a gift to the Sette (and as something of an aggrandisement to his new office!) he commissioned and presented a Vice President’s chair to accompany the President’s.

Those speeches

The Sette's activities were regulated according to a set of Rules, some of which were positively Pythonesque. For example, rule XVI was that 'There shall be no Rule XVI', and Rule XVIII insisted that 'No Odd Volume shall talk unasked on any subject he understands'.

One of the more sensible rules, however (No. XX), stated that 'No O.V.’s speech shall last longer than three minutes; if however, the inspired O.V. has any more to say, he may proceed until his voice is drowned in the general applause'.

Finding that this rule was constantly being disobeyed, and that evidently the ‘general applause’ was insufficient, in December 1891 Heron-Allen also commissioned and presented to the Sette an elaborate speaker’s bell, to ensure they stuck to time.

The bell

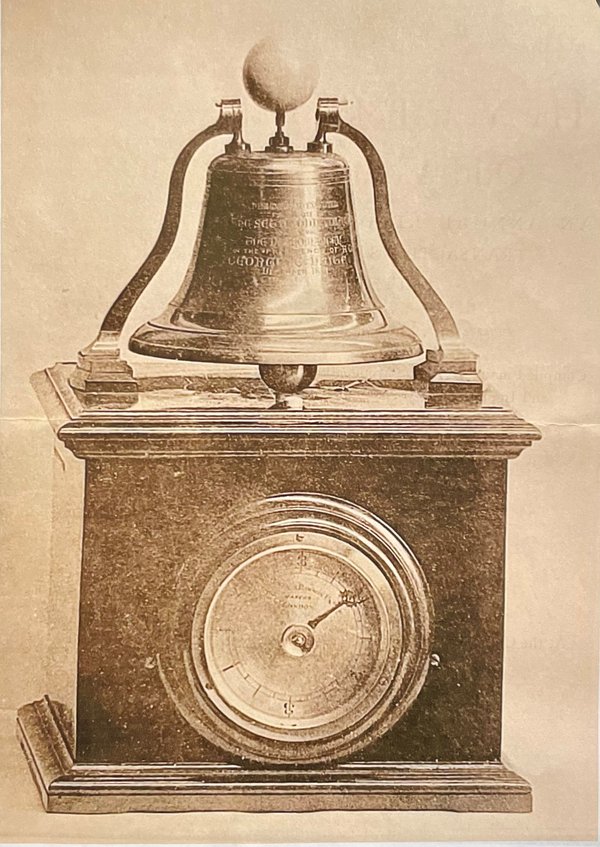

Made by the well-known Victorian electrical engineers, Woodhouse & Rawson, the bell is of exquisite quality throughout. Constructed in a mahogany case containing the electro-mechanical timer, the large bell, mounted on the top, has a slender rod running vertically through it, which had (now missing) a ball on top.

In operation, reminiscent of the way a time ball runs, the timer is set going and the ball (which was probably an ivory billiard ball originally) is seen to slowly climb up from the bell. The ascent is controlled by a clockwork worm-and-fly governor, and at the point at which the three minutes has elapsed, the ball, now about 2.5 inches above the bell, suddenly drops back down to the bell, which then begins to ring very loudly, an electrical make-and-break hammer operating on the inside.

For the speaker, having a miniature time ball inexorably rising in front of him while he was talking must have been quite off-putting and, needless to say, the timing device was not popular. One can only imagine what Oscar Wilde would have thought (and said!) if the thing was set going as he began giving an after-dinner speech!

In fact, a certain flexibility was built into the controls of the bell, and the operator (presumably the Master of Ceremonies) was able to pause the clock, or even ring the bell in advance, if deemed necessary!

But its presence as a gift would soon be quietly but firmly removed anyway, and this fascinating and beautiful object, and the Vice President’s chair, were not seen again. This was owing to an incident which left Edward Heron-Allen unpopular among the elders of the Sette and which caused him to resign from the Sette a year or so later.

The incident, which is described in an excellent book by John Mahoney (The Richard Le Gallienne versus Edward Heron-Allen ‘Incident’ at The Sette of Odd Volumes, privately published, Tallahassee, 2023), concerned the proposal for membership of the Sette of the author and poet Richard Le Gallienne (1866-1947).

Le Gallienne had had a brief affair with Oscar Wilde, and it seems that at the time he was being proposed for the Sette, Heron-Allen had made a remark in confidence at a private dinner party about Le Gallienne’s sexuality. Unfortunately, this remark was not treated in confidence, and Le Gallienne got to hear of it. This would, given the illegality of homosexuality at the time, be a very serious matter for him.

The scandal which ensued polarised views within the Sette, causing Le Gallienne’s election to be dropped temporarily and Heron-Allen to later resign. The chair and timer were thus quietly put away, though the chair does in fact remain in the Sette’s possession; the timer escaped at some stage and only resurfaced a few years ago.

For Heron-Allen the story ended happily, however. He would re-join the Sette thirty years later, and he enjoyed many a dinner with Gould, Holland and his other friends, no doubt having to put up with the long speeches after all.