The AHS Blog

Horology in Oxford museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Long ago I reported on clocks in Berlin museums and more recently on clocks in Lisbon. Let me now direct you to three museums in Oxford, home of the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the world's second-oldest university in continuous operation.

The Ashmolean Museum is the University of Oxford’s museum of art and archaeology, founded in 1683. Its world-famous collections range from Egyptian mummies to contemporary art. It has a large collection of watches, which came to the museum largely as a result of three major bequests. Together these make the Ashmolean collection of watches one of the most important outside London.

You find them on display on the second floor in Gallery 55, and photos with descriptions of some 70 of them on the museum’s website. In 2008, David Thompson, then curator of Horology at the British Museum and currently a Vice-President of the AHS, presented some 30 highlights in a 96-page book which is on sale at the museum’s shop for a mere £5.

The Ashmolean Museum started in a building on Broad Street, and, after it moved to its new premises in the nineteenth century, the ‘Old Ashmolean’ building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, it has housed another University museum, the Museum of the History of Science, or the History of Science Museum as it was recently renamed.

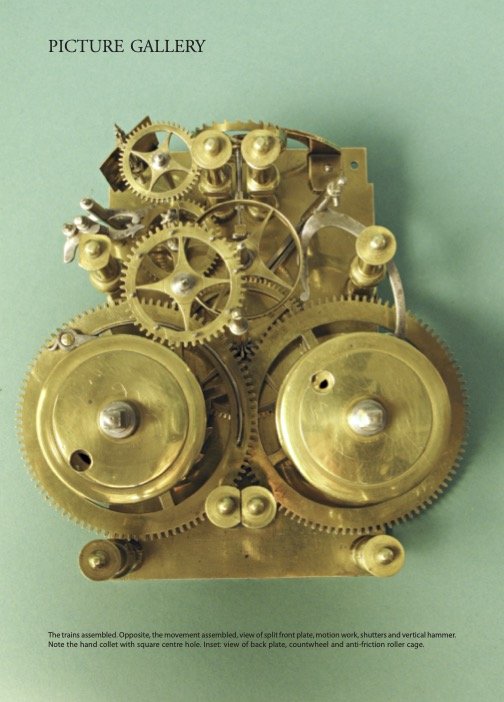

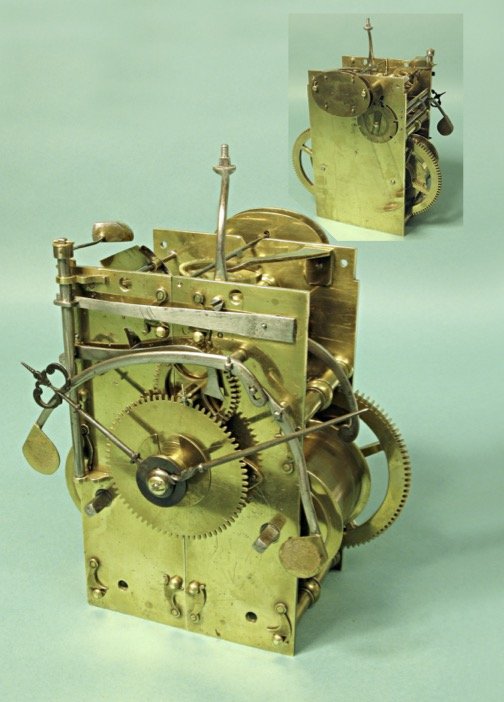

In the entrance gallery stands a longcase clock made by Ahasuerus Fromanteel in around 1660, acquired by the museum in the 1930s and restored in 2008 with financial support from the AHS. This was an occasion for the then journal editor Jeff Darken to present the clock in enormous detail in a 22-page ‘Picture Gallery’ article in the December 2008 and March 2009 journals, of which two sample pages are seen here.

In the basement, more clocks and watches are on display. Two unusual objects in the collection that I particularly like are an oven and an icebox used to check the performance of chronometers at high and low temperatures. They had been used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons.

AHS founder member Michael Hurst (1924–2017) has told me that he and his brother Lawrance (1934–2018) collected the oven and icebox from the Desbois premises in Brownlow Street, Holborn, in about 1955 and stored them on behalf of the AHS in their family home in Hendon. They were later stored by the British Museum and subsequently donated by the AHS to the Oxford museum in 1972.

They are currently in the museum store, but were brought out for an exhibition ‘Time Machines’ in 2011–12, which offered a distinctly inspired ‘new way of seeing the Museum’s exceptional timepieces’. They first featured in my blog ‘Chronometers in hell’, posted on July 26, 2015.

A third place where we find some time-related objects is the Pitt Rivers Museum. It was founded in 1884 by Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827–1900), an English officer in the British Army, ethnologist, and archaeologist, who donated his private collection to the University of Oxford. The museum is entered through the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and through that inner door you step into an amazing Aladdin’s cave brimming with display cases and exhibits.

An unusual and distinct feature of this museum is that the collection is arranged typologically, according to how the objects were used, rather than according to their age or origin. It makes for unexpected juxtapositions. This also applies to the case on the first floor gallery which contains seventeen objects on the theme of time.

To highlight just four, there is an intriguing double-bowl clay pipe with bamboo stem from India, Nagaland, Kaly-Kengu. As the label informs us, ‘Each bowl is smoked separately to measure the time spent working in the fields.´ Top left is a copper water-clock from Sri Lanka, with caption, ‘Such clocks have a tiny hole in the base so that when they are set on the surface of a bowl of water they float for a known period of time. This example is said to sink after 11 minutes.’ From Tyrol, Austria comes the ‘Pewter clock-lamp calibrated to show the time from 9pm to 7am. As the oil in the lamp burnt the level fell, and the time was measured against the markings on the metal stand.’ And from Wimpole Street, London, comes the ‘Sand-glass used by dentists to time the mixing of fillings so they do not de-sterilise their hands by handling a watch. Donated by J. P. Mills 1939’.

Two watches in literature

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

By way of summer entertainment, here are two watches, both regarded with incomprehension but for very different reasons.

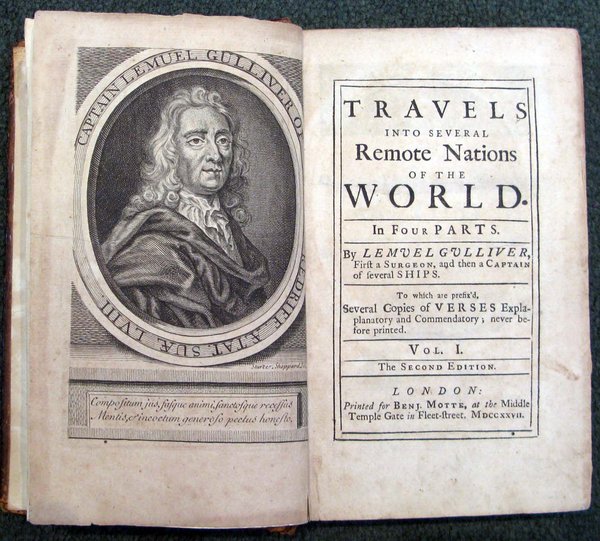

In his famous book Travels into several remote nations of the world by Lemuel Gulliver, published in 1727, Jonathan Swift relates how, during his first voyage of 1699, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches (15 cm) tall, who are inhabitants of the island country of Lilliput.

At the Emperor’s instruction, two officers inspect the contents of his pockets and draw up an inventory. Everything they find – a hairbrush, a snuff box, knives for shaving and eating – is a mystery to them, and the same goes for what they find next.

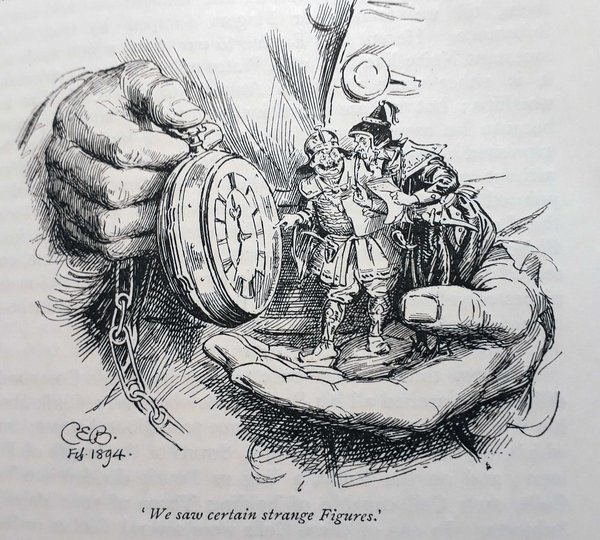

‘Out of the right fob hung a great silver chain, with a wonderful kind of engine at the bottom . . . which appeared to be a globe, half silver, and half of some transparent metal; for, on the transparent side, we saw certain strange figures circular drawn, and thought we could touch them, till we found our fingers stopped by that lucid substance.

'He put his engine to our ears, which made an incessant noise like that of a water-mill; and we conjecture it is either some unknown animal, or the god that he worships; but we are more inclined to the latter opinion, because he assured us (if we understood him right, for he expressed himself very imperfectly) that he seldom did anything without consulting it. He called it his oracle, and said it pointed out the time for every action of his life.'

In 1894, Macmillan published a luxury edition of Travels ..., and commissioned the English painter, line artist and book illustrator Charles Edmund Brock (1870–1938) to prepare one hundred illustrations, including the watch scene.

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (1832–1908) was a German humorist, poet, illustrator, and painter. His wildly innovative illustrated tales have remained in print ever since they first appeared.

Probably the most famous one is Max and Moritz in which two boys are terribly punished for a series of pranks – many of Busch’s stories are not for the faint-hearted! I still treasure the edition I was given as a child, containing a selection for the young of the best-loved tales, all coloured-in (the original published editions were in black and white).

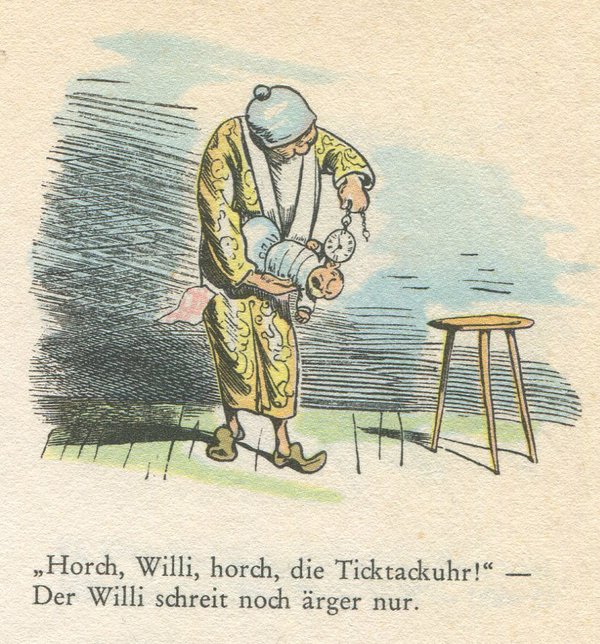

In the story Der Schreihals (The Bawler), dated 1869, we find the second watch. Ever since his mother has bundled him in, the baby boy has been screaming, nothing can make him stop, not even the father who tries to amuse him in various ways, including in the image captioned ‘Hear, little Willy, listen to the tick-tack watch / But Willy simply cries even louder’.

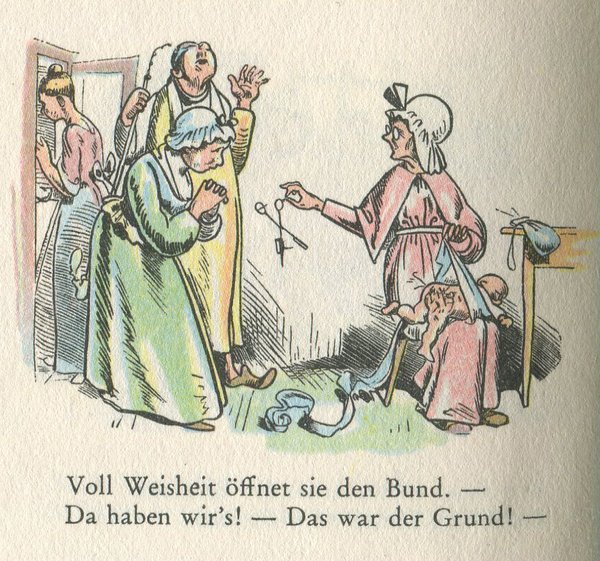

The ordeal only ends when an aunt comes to visit, and ‘Full of wisdom, she opens the bundle / There we have it! That was the cause!’

In the final image, ‘Willy, relieved of the pain / Laughs loudly for pure happiness.’

Clock confusion – think about it!

This post was written by John Laycock

Why do the numbers of 1 to 12 on a clock dial have to be multiplied by 5 to allow one to work out the time?

If there are 24 hours in a day then the daily time continuum is 0 to 24. Why then do mechanical clocks split this continuum into two 12 hour segments? If the continuum has to be split surely it would make more sense to split between day and night with the daylight spanning 6am to 6pm and then night from our 6pm to 6am!

Why is noon 12pm? It is neither am nor pm - simply because we have chosen to reset the continuum at 12! Is midnight 12am? Some digital clocks will show the 60 minutes after midnight as 12.xx whilst others will show the time as 00.xx!

Several attempts have been made to design an unambiguous dial using a 24 hour clock. The modern dial below is a good example.

The most important element is the hour (long hand) with the minutes as secondary (short hand). The dial is numbered with the hours from 0 to 23, as time will be read as hour plus minute and thus 24 will never be appropriate. The shorter hand points to an inner annulus numbered 0 to 55 in steps of 5 to avoid the necessity to perform the mental x5 operation to calculate the minutes or seconds.

Why has this relatively simple and unambiguous display of time not been universally adopted? We still do not think 24 hours we think morning and afternoon.

What about the time warp that occurs when reading minutes? With the minute hand in the right half of the clock face it is usual in the English language to interpret time as 'past the hour' but when the hand moves to the left half of the clock face we usually switch dimension to 'to the next hour' e.g. twenty past six, twenty to seven.

Are we using the clock to display past time or future time? Past time is historical and cannot be used again, future time is at our disposal and should be used to best advantage. Thus the clock face should logically portray future time and not past time.

Taking into account the discussion above making the case for the 24 hour dial, should the numbering system be completely reversed. The dial should display the hours descending clockwise from 23 to 0 and similarly the minutes descending clockwise from 55 to 0 in steps of 5.

Will it happen – NO. We have two much time invested in the past!

The National Physical Laboratory: paving the way for trusted time and frequency across the UK

This post was written by Leon Lobo

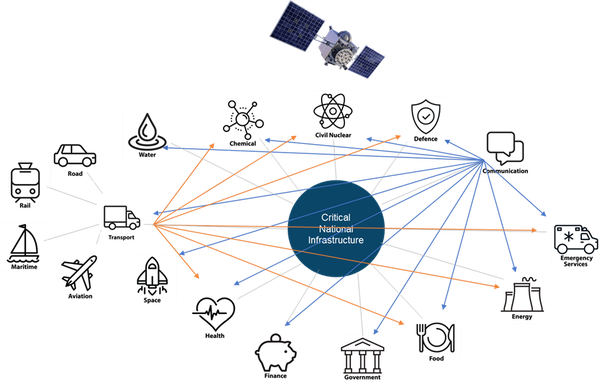

Time is the invisible utility underpinning capability across critical national infrastructure (CNI), as the basis for global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), synchronisation of 5G mobile telephone networks and the energy grid and timestamp traceability critical for trading platforms in financial services.

The world we live in is increasingly digital, with the last few years only accelerating this. We are seeing advances in communication and connectivity and society’s reliance on reliable positional, navigational, and timing (PNT) data is growing.

Many aspects of UK industry and society require increasingly precise time, whether it’s at home on our devices, the telecoms networks, energy, broadcast or in the finance industry where the time margins used are unfeasibly fine: one second for voice trading, one millisecond for electronic trading, and just 100 microseconds for high-frequency trading – all traceable to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the global time scale.

The systems, which rely on PNT signals from GNSS, are robust in themselves and have procedures in place to deal with any GNSS based system faults. However, disruptive interference can occur unintentionally and deliberately, with malicious interference a growing possibility. Potential interferences include jamming GNSS receivers, rebroadcasting a GNSS signal intentionally or accidentally, or spoofing GNSS signals to create a controllable misreporting of position.

An alternative timekeeping source is crucial to help prevent any serious impact to all of the above if something were to occur to the signals received via GNSS. They will also future proof society as we develop smart cities, autonomous vehicles and communications.

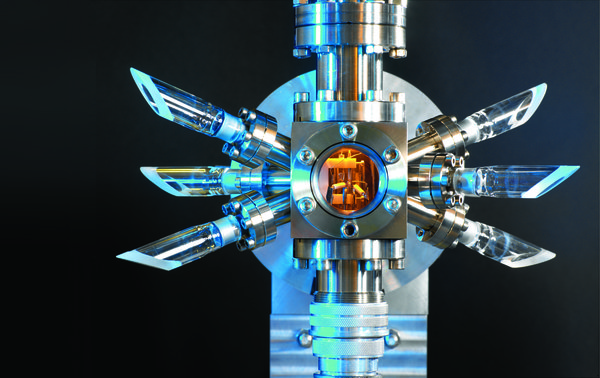

To mitigate these issues and vulnerabilities, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), through its National Timing Centre (NTC) programme, is developing an alternative, potentially primary solution for future timing. The team and I are striving to ensure that the UK digital infrastructure is supported by a GNSS-independent sovereign capability for time moving forward. I am keen that we become more aware of our dependency on GNSS and start to consider how we do things differently. Dependence by default on this space asset is no longer tenable without due consideration for resilience of operations.

The NTC programme will provide the resilience needed to protect critical national infrastructure, keeping essential services running and ensuring trust in new technologies. It will enable the UK to move away from reliance on GNSS, like GPS, for time, and leverage a range of time and frequency distribution technologies including fibre, communication satellites, and terrestrial broadcasts, alongside GNSS.

NPL’s NTC programme aims to deliver a resilient UK national time infrastructure through the building and linking of a new atomic clock network distributed geographically in secure locations. It will also provide innovation opportunities for UK companies through funding projects in partnership with Innovate UK based on a successful NPL and Innovate UK partnership model. Finally, the programme will respond to the specialist skills shortage in time and synchronisation solutions through specialist, apprentice and post graduate training opportunities.

Improved resilience will help to strengthen our society through faster, more secure internet, robust energy supplies and reliable health and emergency services. As a community that understands timing and timekeeping, I am keen to have you engaged, raising awareness of why time is important to our daily lives and what we need to consider to ensure we have resilient time for the future.

Dr Leon Lobo is Head of the National Timing Centre at the National Physical Laborartory, whose work focuses on developing and delivering the UK's national timing strategy. Having worked at NPL since 2011, Dr Lobo has led the team managing the UK’s time scale and supported on the development of NPLTime®

The perils of poor lubrication and a potential solution

This post was written by JC Li

We all know the perils of poor lubrication: creeping oil, deterioration, wear… the list goes on. Good lubrication is paramount to the correct functioning and prevention of wear for horological mechanisms. Although modern synthetic oils have come on in leaps and bounds from the old-school vegetable oils and refined whale blubber, it can still prove challenging to ensure that they don’t ‘creep’ away from friction points to other areas. Where there is friction without oil there is wear, which can impede functionality and result in irreversible loss of material.

One solution used by some watchmakers is to apply a thin oleophobic (oil-repelling) coating known as epilame which helps retain oil at critical points, particularly in the escapement. However, it does not appear to be used as commonly by clock makers and repairers, typically oiling their escapements in the traditional way with no surface coating. As The Practical Lubrication of Watches and Clocks by the British Horological Institute (2008, p.15) states:

'Surface treatment to prevent spread of oils is not commonly used in clocks but can have similar advantages to its use in watches.'

As an MA Horology student at West Dean College, I’m hoping to establish through my thesis whether the use of modern epilame products such as Moebius Fixodrop or Episurf-Neo could be a conservation-grade solution to oil creep on pendulum escapements.

As such, it would be of great help to me if readers could respond to my two-minute survey about this topic, both in order for me to gauge current practices and also receive some feedback on this research. I equally welcome any pointers in this area of study or any relevant anecdotes of personal experience about oiling escapements, epilame, or any of the other issues referred to. I can also be contacted using my West Dean email address: s21jl@westdean.ac.uk. Thank you.

An animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement

This post was written by Eliott Colinge

Visual representation has always been a core means to learn about horology and explore its principles.

The literature provides countless invaluable schematics about escapements, repeating mechanisms and patents of all sorts. Less can be said about video representations. If an image is worth 1000 words, what can be said about a video?

The recent popularisation of 3D animation in the film and gaming industry has gathered a wide community of brilliant individuals giving their improvements to the field at an increasing pace.

It is hardly possible to have a conversation about 3D animation without hearing the word 'Blender'. Being open source, the software has attracted students, researchers, professionals and amateurs around the world and is increasingly becoming a standard in the industry. Blender is such an incredible playground and I am always in admiration of what gets produced by the community.

As a trained conservator of horological artifacts, I founded the animation studio 'Vecthor' to provide complementary 'non-interventive' solutions to help education around collections.

Vecthor has made available a series of short animations of escapements based on drawings and a YouTube video about Pierre Leroy’s marine watch (available in English and French).

Here is an example through an animation of Thomas Mudge’s constant-force escapement used in his marine chronometers during the 1770s. The impulse energy is stored in the coiled springs (constant-force) and transmitted to the balance during its oscillatory arc.

Other escapement animations can be found on Vecthor's instagram: @vecthor_animation

High-frequency quartz watch fails to resonate

This post was written by James Nye

After the Second World War, Smiths pioneered rebuilding a watch manufacturing industry in Britain. It partnered with Ingersoll to make inexpensive watches in Wales, and developed high-grade watch manufacture at Cheltenham.

Despite achieving strong brand recognition, the economics never worked. Smiths lost money on every watch made at Cheltenham, subsidised from elsewhere in the business. Foreign exchange, material shortages, foreign dumping and more offered overwhelming challenges.

Into 1970 and the head of the clocks and watches division announced a plan to use Swiss watch movements, but in September 1970, Smiths’s CEO announced watch production would cease at Cheltenham, achieved by March 1971.

However, a small team under Dr Shelley of the Special Horological Products Unit continued the development of a cutting-edge quartz watch – the Quasar – launched at the Basle Fair in 1973.

A few hundred pre-production watches were produced. The senior Smiths staff tested them, and when I interviewed some of them ten years ago, a few were recovered from bottom drawers.

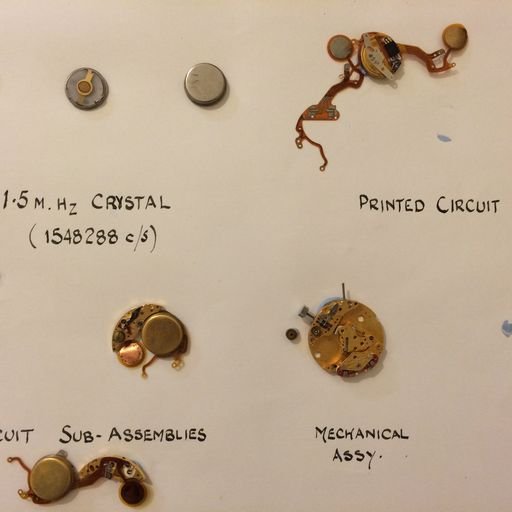

One of them was donated and is now in the Clockmakers' Company collection. Through similar generosity, the Clockmakers received a second watch, and also ephemera, including a rough card mounted with parts of the Quasar assembly.

Smiths used an AT-cut quartz crystal, not the normal XY cut. It resonated at 1.5 MHz, against the standard 32,768 Hz, and Smiths actually made this in-house, targeting high performance.

But this came at a price, in size, leaving little room for frequency division. Indeed, ‘conquering the division problem’ was the main achievement remembered years later by former senior Smiths managers.

Omega made a success of their 2.4 MHz AT-crystal watch, but bar or tuning-fork crystals of much lower frequency would soon dominate the mass market in watches by Timex and Junghans. Importantly, Seiko’s 38 Series watches had a frequency of 16,384, achieving better accuracy than the Quasar, with a frequency one hundred times lower!

Volume production of the Quasar never started – Smiths had stacked the odds against itself.

There were problems with the US supply of circuit boards, the stepper motors were hand-wound in Cheltenham, and in-house manufacture of the crystal was both expensive and inefficient.

Pricing was to be pitched at £70 in late 1973, but while watches were still being tested on the wrists of senior management, the chairman and MD of Smiths visited Seiko’s factories, and what they saw convinced them to pull the plug on the Quasar.

Until fairly recently, Quasars had remained essentially invisible – almost mythical. But at a remote auction, a Cheltenham watchmaker's effects turned up. Even if Smiths stopped work in 1973 or so, at least one person kept testing the pre-production samples.

Tags record watch 485 with crystal 419, and watch 365 with crystal 365, faults being found, and adjustments being made.

While the fossil record retains little evidence of a watch that never made it to market, some evidence of its development has nevertheless been preserved.

Clocks in Lisbon

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Any horologist visiting Lisbon will want to visit the Casa-Museu Medeiros e Almeida, situated just off the majestic Avenida de Liberdade: https://www.casa-museumedeirosealmeida.pt/

It is the house where the Portuguese businessman António Medeiros e Almeida (1895–1986) lived and which he filled with his private collection of objects of decorative arts, including a collection of clocks and watches. It opened as a museum in 2001.

As explained in the catalogue, which I reviewed in Antiquarian Horology in December 2019, it 'consists of a core of about 650 items. [...] The timepieces cover a period of five centuries and are from France, England, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Italy, Portugal, Russia, China and Japan'. A special gallery was created for them, but clocks are also found in many other rooms.

However, I want to direct you to two other clocks elsewhere in the city.

The first is in the Military Museum, a distinctly old-fashioned – but to me rather inspiring – place; some photos can be found on http://www.exercito.pt/pt/quem-somos/organizacao/ceme/vceme/dhcm/lisboa. On display in one of its enormous rooms is a turret clock with a plaque explaining (I translate from the Portuguese):

'Constructed in Lisbon in the 18th century by the clockmaker F. Baerlein, it was the only turret clock in the neighbourhoods of Santa Apolonia, Santa Clara, Alfama, and surroundings. It commanded all the clocks in the various establishments of the Royal Armoury of the Army, and also serving the population of the nearby areas as well as the crews on the ships on the river Tagus. After being struck by a grenade in May 1915, it stopped functioning. It was repaired in March 1957 […], which the staff of the Military Museum have marked with this plaque.'

A web search found nothing on the maker. What I did find was a photo of the base of a lamp post in Lisbon with the name F. BAERLEIN. Clearly later than the clock movement, but then, perhaps Baerlein had successors in the city?

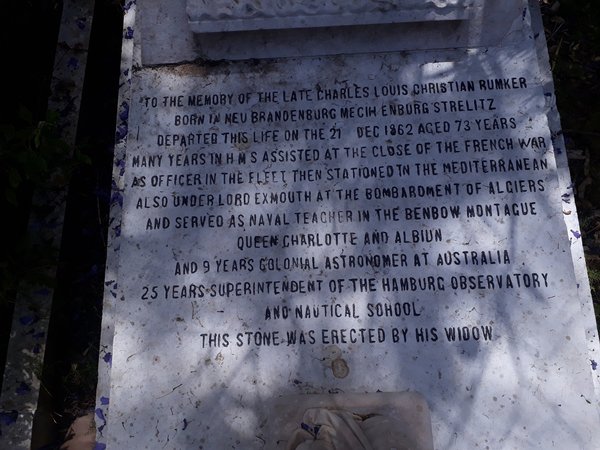

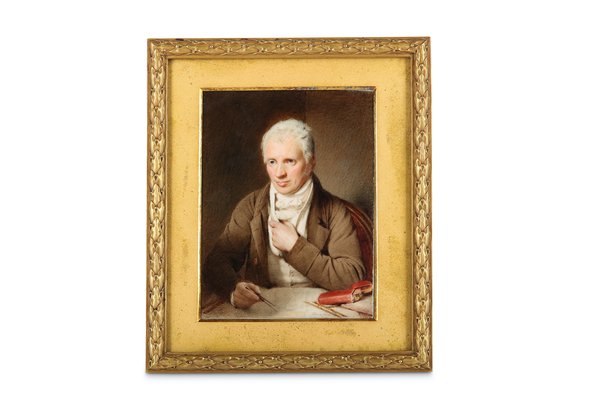

For the second clock, one must enter the beautiful British Cemetery https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/ located opposite the Estrela Park. Tourist guides invariably single out the memorial to the author Henry Fielding (1707–1754), best known for his novel Tom Jones. But to me of far greater interest is the memorial erected for the German-born Charles Louis Christian Rümker (1788–1862) https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/interesting-monuments which was the subject of an article by Julian Holland in the Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society No. 77 (2003), pp. 32-35.

Rümker served as colonial astronomer in Australia and later as superintendent of the Hamburg Observatory and Nautical School, and the monument shows the tools of the astronomer, including a clock.

While funerary monuments often show an hour glass, symbol of the passing of time, the representation of a clock is certainly rare, perhaps even unique? I would be interested if anyone knows other examples.

Inspiring people with horological collections: a guide’s perspective

This post was written by Robert Lamb

Since October 2015, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection of clocks, watches and associated objects has been displayed in its new home at the Science Museum, where it is accessible to the public whenever the Museum is open.

I have been conducting 60-minute tours of this wonderful historic collection on a monthly basis since July 2019. Despite needing to pause during the pandemic when the museum was closed, myself and the other volunteer guides have been back up-and-running since October 2021 and we hope that the frequency of the tours will increase as more volunteers join the team.

So, what happens on my tours?

Firstly, I introduce myself to the group and enquire if anyone has any specific interests. Participants are a pretty eclectic mix of those who, by chance, saw the notice at reception, those who came especially to see the collection, inquisitive tourists, and passers-by who show an interest and I cajole to join!

I then explain that we will not cover the whole collection, but will be honing-in on specific objects and groupings or significant topics and people.

I always like to give a short introduction to cover the origins of the collections, history of clockmaking and development of London’s Livery Companies.

Having gauged the mood and interest of the group (not forgetting that children may need entertaining too!), we often start with the introduction of domestic clocks in Europe and London, followed by the later need for more accurate timekeeping. Often, we look at the introduction of the pendulum and I talk about the development of clocks in London with the knowledge brought back by John Fromanteel. We are regularly drawn to John Harrison and his fight for recognition to win the Longitude Prize and then become fixated by H5!

There are so many tales to tell of the many objects we encounter. I love the one of an early Master of the Company, whose role was to keep the Company chest (which contained the silver and significant documents) at home during his tenure, but couldn’t get it through his front door!

No two tours are ever the same, which gives me great pleasure and I hope it does this for the participants.

Joining a tour is the only way to see what actually happens – visit the fabulous collection yourself and soak up the wonders of such a diverse horological history!

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

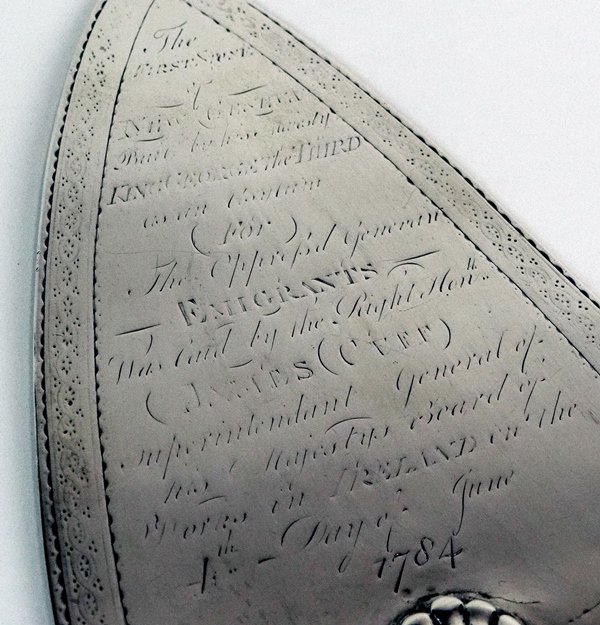

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

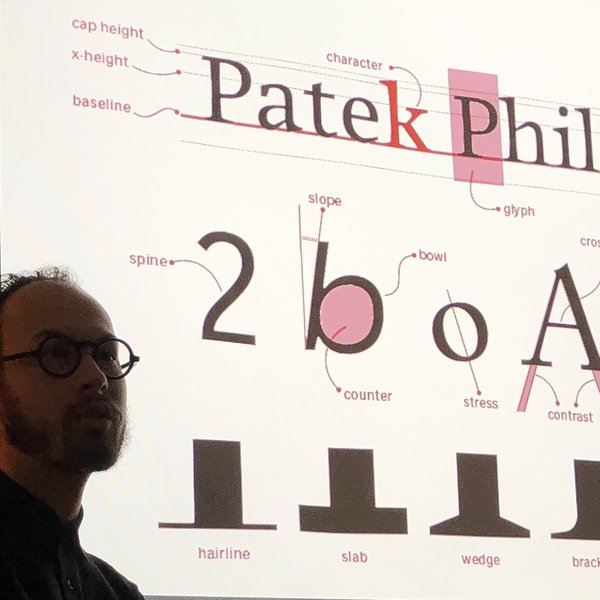

A few examples of contemporary typography in watchmaking

This post was written by Lee Yuen-Rapati

The evolution of typography in horology has come a long way from the dominance of Roman numerals and the round hand script. While the mid-twentieth century remains a potent library of inspiration for today’s watch brands, other watchmakers look forward in creating their timepieces.

These contemporary watches can appear non-traditional or even avant garde, with typography to match. However a closer look reveals that even the newest typography on watches still has connections to the past.

The use of bold and blocky sans-serif numerals is a common trend in many contemporary watches that try to eschew a sense of antiquity, at least on the surface. A prime example is the collection from Urwerk who have consistently used a bold and angular style of numerals since their inception in the late 1990s. The ultra high-end pieces from Greubel Forsey also feature rather rectangular numerals which both match the aesthetics of their main collection, but provide an interesting juxtaposition in their Hand Made 1 as well as the Naissance d’une Montre (1) watch, both of which highlight more traditional watchmaking techniques.

The use of bold and blocky numerals is more of an evolution for a company like Rolex who have adopted them across their recent collection, notably on the Explorer and GMT-Master II models. While none of the examples above are likely to be mistaken for antique pieces, similar rectangular or blocky numerals were popular in the art deco era and into the mid-twentieth century. Even if the watch is new, the link to the past is sometimes quite prominently promoted as with the unabashedly contemporary (and divisive) Code 11.59 collection which features numerals adapted from a 1940s Audemars Piguet minute repeater.

Some contemporary watches pull from outside the horological world to define themselves. Hermès as well as the young company anOrdain each sought out type designers to create new and identifiable typography. Hermès got its modernist numerals from the studio of Philippe Apeloig for its Slim d’Hermès line while anOrdain’s typographer Imogen Ayres created numerals inspired by survey maps. Neither brands’ numerals are completely new, but their lack of typographic precedence in the watch world make them both stand out.

Other brands use more traditional numerals but change the material in order to place their watches firmly in the twenty-first century. H. Moser & Cie’s Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue uses applique numerals that are inspired by 1920s pilot’s watches. The appliques are made from the luminous material Globolight rather than metal. In a similar fashion, the refounded British brand Vertex uses moulded Super-LumiNova numerals in lieu of traditionally painted or printed numerals on their military-inspired watches. Kari Voutilainen offers the option for brightly coloured arabic appliques on his watches which bring a youthful presence to his more classically designed dials. Dimensionality has long been a useful styling tool for watchmakers, and the inclusion of new materials has produced some very refreshing results.

The examples above represent a few different typographic paths for the contemporary watchmaker to follow. While these watches and their typography may appear to share very little with antiquity, there are always links to trace back, they are simply being shown from a new angle.

Photo credits:

- Baruch Coutts @budgecoutts (Urwerk, UR-UR111C)

- Greubel Forsey (Hand Made 1)

- Atom Moore @atommoore (Rolex, GMT Master II)

- Audemars Piguet (Code 11.59 Selfwinding White)

- Baruch Coutts (Hermès, Slim D’Hermès Titane)

- AnOrdain (Model 2 Blue Fumé)

- H Moser & Cie (Heritage Centre Seconds Funky Blue)

- Vertex (M100)

- Atom Moore (Voutilainen, TP1 OW2019)

The engineer’s chronometer: William Wilson and the Adler

This post was written by Allan C. Purcell

Last Summer I bought on eBay this fusee chain driven watch with detent escapement, dia 50mm, hallmarked Chester 1858, signed on the movement ‘William Benton of Liverpool, No. 5115’, and on the dial ‘Chronometer watch by William Benton 148 Park Road Liverpool’.

In the description of the watch, the seller had written ‘Opening below to reveal a highly decorated dust cover “Stephenson’s Rocket, Steam Train”, and clean fully working highly decorated “Steam Paddle Ship”.’

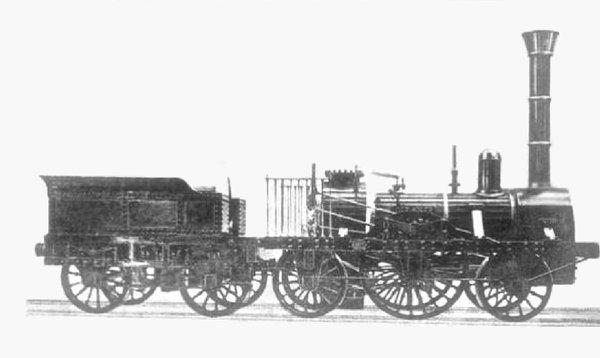

What the seller failed to point out is that the watch is inscribed on the dustcap ‘WILLM WILSON / LIVERPOOL / AD 1859’. It is my belief that this was the English engineer William Wilson (1809-1862), and that the locomotive illustrated on the watch is not the Rocket but the Adler (German for: Eagle), the first locomotive successfully used commercially for the rail transport of passengers and goods in Germany.

In 1835, George & Robert Stephenson in Newcastle were contracted by the Bavarian Ludwig railway company to build an engine for their first railway to run from Nuremberg to Furth. They sent the new locomotive packed in boxes, and their engineer William Wilson was contracted to rebuild it there. The train was a huge success and Wilson stayed with the Ludwig railway company for another twenty-five years, driving the train in all weathers. In 1859, William was covered in glory by the German railway company. In 1862 he died and was buried in Nuremberg, where his descendants are still living.

While Stephenson’s Rocket has only four wheels, the Adler had six wheels (wheel arrangement 2-2-2 in Whyte notation or 1A1 in UIC classification). The engraving on the watch shows a locomotive with six wheels. The image of the ship engraved on the watch may refer to the steamboat Hercules which in September 1835 had been used to transport the boxes containing the locomotive from Rotterdam on the Rhine to Cologne.

When in September last year I went to Nuremberg for the Ward Francillon Time Symposium, I arranged an appointment with Stefan Ebenfeld, the director of artefacts and library at the Museum of the German Railway (Deutsche Bahn Museum) in Nuremberg. It turned out that the museum had no personal artefacts of Wilson’s, and we agreed that the museum would buy the watch from me for the price I paid for it.

For anyone interested in more details, there are entries on William Wilson and the Adler on Wikipedia.

The typography of revival watches

This post was written by Mat Craddock

Until recently, there had been little research carried out on the typography of wristwatch dials. However, over the past decade, the increased interest in collectable vintage wristwatches appears to have sparked the interest of brands and collectors alike.

While wristwatch collectors’ focus has largely been on the variations in logo, layout and content of vintage wristwatch dials, interdisciplinary designer Lee Yuen-Rapati has taken a critical look at the typefaces used, and typographic decisions made, by watchmakers.

His Masters dissertation, titled ‘Motivating Factors In The Trends Of Horological Typography,’ formed the basis of an AHS Wristwatch Group talk at The Clockworks in April.

Lee’s research covered clocks, pocket watches and wristwatches, and looked at type and numerals used on the dials, identifying various themes and typographic pitfalls that appeared to be specific to wristwatches.

His research included interviews with brands and independent watchmakers about their typographical decisions, the typefaces they use and the importance of type design to their brand.

His talk focused on the typography of contemporary wristwatches that had revived distinct vintage or antiquarian styles.

Highlights included the use of system (or default) fonts by high end watch manufacturers, the technical limits of pad printing, the benefits and traps of modern processes involved in dial design (such as the digital workspace) and inconsistent choices made by watch brands when reviving older designs. Examples of recent wristwatches from Longines, Nomos and Stowa were used to illustrate these themes.

As a codicil, Lee discussed recent advances in dial printing, such as the use of physical vapour deposition on the zirconium ceramic dials of the Charles Frodsham Double Impulse Chronometer, suggesting that this technology might be taken up by other watch manufacturers, necessitating an increased focus on typographical principles and design choices.

Follow The AHS on Instagram: @thestoryoftime

Lee Yuen-Rapati: @onehourwatch

Mat Craddock: @the_watchnerd

And now for something different

This post was written by David Read

In the world of watch collectors there are many who dislike finding that a pocket watch case has been engraved with the owner’s name, or to record it being given as a present. My feelings are different. An engraving not only provides a date which can be useful information, but can also point to an interesting history.

Late one evening in November 2000, I was watching a BBC documentary about the Yukon Gold Rush when the name Skookum jumped out at me.

In turn, I jumped out my chair because some years earlier at a NAWCC meeting in Florida, I had acquired a 14 karat gold E.Howard & Co. pocket watch retailed by Joslin & Park of Denver Colorado.

E. Howard & Co. made some of the finest watches in America so it interested me, as did the inner back which was not the same colour of gold as the rest of the case. And engraved on it were the words, 'A relic of Skookum Gulch March 22nd 1897'. It was certainly something different.

When the Yukon documentary finished, some quick research on the Internet led me to an email address for the Yukon Prospectors Association and before going to bed I sent questions with attached images.

In due course I received a reply from a member, himself a prospector who had searched for gold and experienced the thrill of finding it.

The following summarizes what he wrote:

'Gold was first discovered at Skookum Gulch by Joseph Goldsmith and his partner on 22nd March 1897, the date engraved on your watch. Arriving in the Klondike area too late to stake a claim on one of the major creeks, he prospected the feeders and found rich gold in this one. Goldsmith staked the first claim and named the stream. He, or perhaps his partner, used some of the gold to have a replacement inner cover made for the watch. The gold will be from the original panning and is significant in that it marks an historical event'.

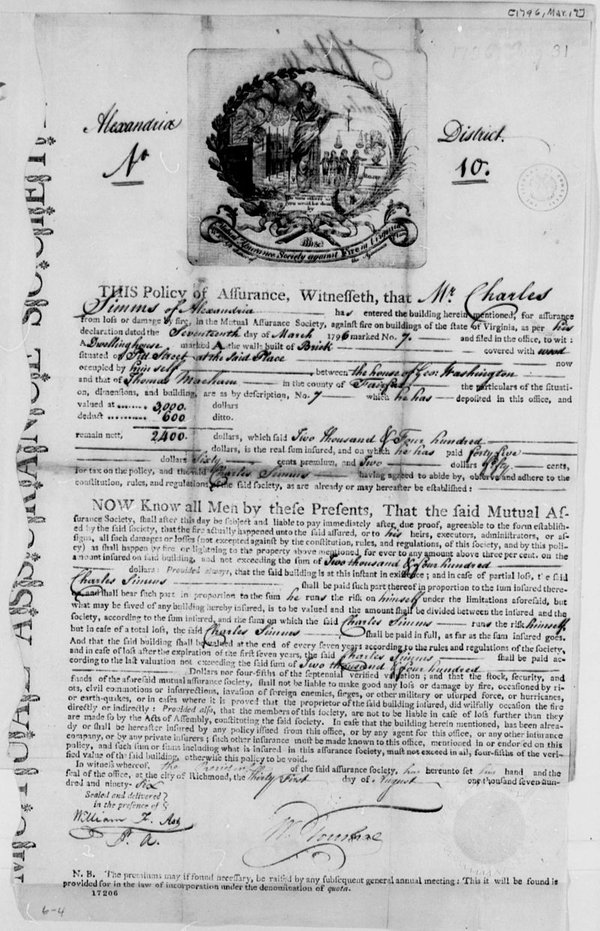

Fire! Fire!

This post was written by James Nye

The AHS has launched a fascinating new research resource for its members – a series of searchable fire insurance records, covering the period 1710 to 1863.

Over many years, the late Roger Carrington (1948–2005) manually transcribed fire insurance records now held at the London Metropolitan Archive (LMA), and his work has been digitalized and added to the AHS web-site.

The LMA catalogue describes the holdings of a ‘substantial, if incomplete series of fire policy registers’ which survive for several insurance companies, including Sun Life (from 1710 to 1863), and Royal Exchange (from 1754 to 1759, and 1773 to 1863).

Roger focused on the policies of clockmakers and watchmakers, and related trades.

We have created downloadable and searchable pdfs. The key benefit is the digital searchability of all six thousand one hundred and twenty records involved.

What can one discover?

Well, as the catalogue notes indicate, ‘Where fire policy registers exist, they generally include the following information: policy number, name of agent/location of agency; name, status, occupation and address of policy holder; names, occupations and addresses of tenants (where relevant); location, type, nature of construction and value of property insured; premium; renewal date; and some indication of endorsements […] Sun Fire insurance policies were renewed after five years at which time a new policy was issued under a new number.’

The data are of great interest to the horological researcher for a wide variety of possible reasons.

The records can be searched for the name of a clockmaker, watchmaker or anyone involved in related trades. If the relevant name appears, the details of a policy can then be reviewed – potentially revealing new and interesting contextual material (e.g. verifying an address for a given date range, indicating prosperity or lack of it, etc.)

The records could be interrogated in a different way, for example by location, occupation or street name.

Many will find the searchable pdfs sufficient, in simply locating information to be found in the main policy transcriptions. However, some may wish to do more with the data, and to this end we have provided an index in Excel, which will allow for more sophisticated searches of the data.

This valuable resource is only available to AHS members, so do join up if you think it might be useful in your research. AHS membership is terrific value and your subscription helps support our mission to foster the study of the story of time.

Wristwatch Group meeting, 14th January: conservation and restoration

This post was written by Mat Craddock

In the gas-fired warmth of the Royal Arcade, WWG members heard Justin Koullapis (our gracious host, The Watch Club), Adam Phillips (casemaker and restorer), Greg Dowling (WWG member and watch collector) and Oliver Cooke (Curator, Horological Collections at the British Museum) discuss originality in watches.

Oli’s curatorial view of conservation was, perhaps, the most extreme: once an item enters a collection, the aim is to put it into stasis, free from the damaging effects of winding or lubrication.

From a collector’s point of view, Greg said that the possibility of wearing and using a watch might lead him to seek out to the most appropriate way to restore the piece to working order.

Adam agreed, and seemed largely happy to undertake work under the direction of his customers, taking the view that sensitive restoration and repair can extend the useful life of a watch.

Justin’s thoughts on the subject were from two, contrasting, points of view: as a non-practising watchmaker and as a watch dealer. He said that great value is placed on entirely original objects, many of which have been hidden away for many year. However, his fascination with how objects were made often caused him to place more value on the skills of the watchmaker, rather than the watch itself.

Questions were taken from the audience, and covered topics such as dealer versus collector (the panel was split on the definition of a collection); the dangers of old radium (the British Museum has their luminous watches stored in steel-lined rooms that are externally force vented); and even the purpose of collecting watches.

In response to the last question, Mr Dowling quoted from the late Dr George Daniels: there’s nothing more attractive than a good watch. It’s historic, intellectual, technical, aesthetic, amusing, useful.

A fitting end to an interesting evening.

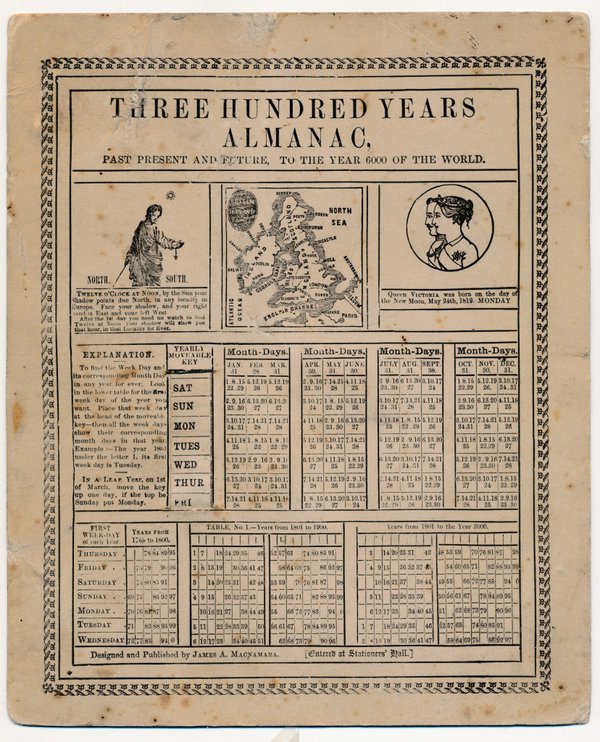

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ Time Machine: perpetual calendar or not?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

I am fascinated by gimmicks used by past watch manufacturers to make their products stand out in a crowded marketplace and this post is the first in a short series on some attention seeking watches that have piqued my interest.

This post takes a look the Wittnauer ‘2000’, a quirky automatic wrist watch from the 1970s.

It is a snazzy-looking chunk of a watch and is impressively big at 46mm across the case and crown; the dial does not disappoint with its day, date and complex-looking calendar information around two apertures at twelve and six o’clock.

It was advertised in the early 1970s as a time machine with perpetual calendar, which is technically correct but arguably a little misleading.

The perpetual calendar is a celebrated complication prized by collectors of high-end wrist and pocket watches.

The intricate mechanism required to keep the calendar in step with the short months and leap years demands multiple precisely made components, is only found on the best watches and, unsurprisingly, its presence in a watch hikes the value substantially.

Stephen McDonnell’s recent innovative perpetual calendar design. Uploaded to Youtube by Quill and Pad.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ has a perpetual calendar, which does conform to the same definition.

The date display is a standard type, which must be manually advanced at the end of a short month. It is more normal for the calendar to be set using the crown, but why do that when you can have an extra button on the outside of the case? Instead of keeping the date in sync, it uses tables and a revolving scale to reckon the day of the week for a given date.

The mechanics of the design are very simple, the revolving disc has a contrate gear on its reverse, which is driven by a pinion attached to a second crown.

The years and days of the week are printed on the revolving disc and, as can be seen in the image, aligning the year with the month on the lower table (at six o’clock), places each day of the week above one of seven columns (at twelve o’clock) that contain the relevant days of the month.

The Wittnauer ‘2000’ perpetual calendar employed an old and simple technology to allude to luxury. For a modest price it had bags of 70s style and, as with any self-respecting time machine, had buttons aplenty!

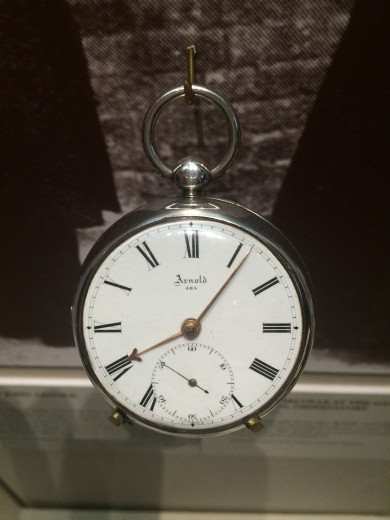

How did Arnold get to the Clockmakers’ Museum?

This post was written by David Rooney

On 23 October, the Clockmakers’ Museum opened at the Science Museum. The new gallery is a treasure-trove of horological history, home to so many wonderful items it’s hard to know where to look next.

Tucked away in one showcase is a modest-looking pocket watch that would be easy to miss, yet tells a story close to my heart—that of Ruth Belville, whose biography I wrote in 2008.

The watch was originally the property of John Belville, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, who used it between 1836 and his death twenty years later to carry accurate Greenwich Time round a network of subscribers across London.

When John died in 1856, the watch was passed to Maria, his wife, who continued carrying it round London until 1892, when she retired.

She then passed it to her daughter, Ruth, who named it ‘Arnold’ after its maker, John Arnold. Ruth carried the time to town with Arnold until 1940, when she retired, aged 86.

But it was not the end of the line for Arnold. Ruth had always wanted it to have a good home.

‘When it retires from business … I think the dear old thing ought to be put in the British Museum’, she told the Evening News in 1908. In 1921, Ruth changed her mind, stating that she ‘should wish the Royal Observatory to have the first offer of purchasing my chronometer’.

Yet neither received Arnold.

In 1941, the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers granted Ruth a pension which gave her crucial financial security in her retirement.

Ruth repaid its generosity in January 1943, when she wrote to the Company offering her watch for its museum when the time came. The Company accepted, noting that ‘by doing so her name would be perpetuated for all time’.

Eight months later, Ruth died with Arnold by her bedside. The watch was duly transferred to the Company’s collection and ended up on display at Guildhall.

Now I needn’t go to Guildhall to see Arnold—delightful though my visits there always were—but instead I can pop into the magnificent new gallery at the Science Museum during my lunch break.

I hope you’ll have a chance to see it too.

Inaugural meeting of the AHS Wristwatch Group

This post was written by Mat Craddock

On Thursday 29th October, the AHS’s first new Group in over forty years held its inaugural event.

The Wristwatch Group, whose aim is to further research into, and to increase the understanding of, wristwatches, has been working with one of the oldest and prestigious names in watches, Montres Breguet SA, to host the event.

Breguet’s newly-opened three storey boutique on Old Bond Street was the perfect venue, with vintage pieces on display alongside current models, many clearly showing a direct lineage from Abraham Louis’ extraordinary and often revolutionary designs.

One of Breguet’s in-house watchmakers guided guests through the often bewildering complications and materials on these modern watches, which are now just as likely to be using titanium and silicon, as brass or gold, such as the Breguet Tradition 7077.

This fascinating new piece is a bifurcated model with two movements working independently at different frequencies: a relatively traditional time-only mechanism (3Hz); and a 20-minute chronograph operating at 5Hz.

The evening was introduced by Jonathan Betts MBE on behalf of the Chairman of the Council, and was followed by two talks by two of this country’s most knowledgeable Breguet experts, Andrew Crisford and Stuart Kerr.

Jonathan’s introduction also paid respect to AHS President Lisa Jardine, a firm supporter of the Group, who had sadly passed away a few days before.

Andrew drew parallels between modern wristwatch marketing practices, such as product placement, the use of brand ambassadors and accessorising, and the pioneering efforts by Abraham Louis.

It seems that even in the early 19th century, Breguet was ahead of the game. Stuart began his talk by describing the circumstances that lead to the Longitude Act, via the alleged murder of Sir Cloudesley Shovell on the sands of Porthellick Cove. Shovell’s pocket watch, an English verge had recently been brought into the boutique and was, along with some of Andrew’s Breguet-related paraphernalia, available for guests to view.

BHI Clock & Watch Conservation and Restoration Forum, 5th September 2015

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Earlier this month the British Horological Institute hosted a day of lectures and discussion relating to horological conservation and restoration at their headquarters in Upton Hall.

![Upton Hall, headquarters of the BHI (Image: Andy Stephenson [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/Upton_Hall_-_geograph.org_.uk_-_4563-1.width-600.jpg)

The terms 'conservation' and 'restoration' are applied to different philosophies of approach to maintaining and repairing objects.

Conservation typically describes an approach of minimal intervention, i.e. attempts to preserve the existing material of a clock or watch as far as possible, whilst still enabling it to serve its required use.

Restoration can describe attempts to revert a clock or watch (that has received alterations over the years) back to its conjectured original state. This typically involves involves the alteration or removal of existing material which, even if not original to the object, can be considered to be part of its history.

There are proponents and opponents of each approach, with many falling somewhere in-between.

There is no black or right – every conservation project is different. The differing motives of the stakeholders (who might include horologists and their clients, or visitors to a museum) and the intended use of an object are all valid considerations in the decision-making process which affects the outcome of a project.

The forum aimed to explore these issues through a series of talks from professionals in the field.

The AHS was very well represented with six of the seven speakers being members:

Ken Cobb – Welcome and Introduction

Alison Richmond – ICON’s Perspectives

Matthew Read – Conservation Training and Education in Horology

Oliver Cooke – Managing Dynamic Objects in Museum Collections

Chris McKay – Conservation on Larger Objects (Turret Clocks)

Keith Scobie-Youngs – Working with Others – Project Management within Conservation

Jonathan Betts – Conservation/Restoration for the National Trust and Other Heritage Organisations

The forum ended with a positive and interesting open panel discussion.

One of the key messages of the day was that the BHI and all horological practitioners have a key role in helping to educate, as widely as possible, all stakeholders in the conservation process on these issues because only with this knowledge might they know how their decisions in the present will affect our heritage in the future.

The forum was thus a very positive contribution towards this vital aspect of antiquarian horology and Kenneth Cobb and the BHI must be lauded for making it happen.