High-frequency quartz watch fails to resonate

This post was written by James Nye

After the Second World War, Smiths pioneered rebuilding a watch manufacturing industry in Britain. It partnered with Ingersoll to make inexpensive watches in Wales, and developed high-grade watch manufacture at Cheltenham.

Despite achieving strong brand recognition, the economics never worked. Smiths lost money on every watch made at Cheltenham, subsidised from elsewhere in the business. Foreign exchange, material shortages, foreign dumping and more offered overwhelming challenges.

Into 1970 and the head of the clocks and watches division announced a plan to use Swiss watch movements, but in September 1970, Smiths’s CEO announced watch production would cease at Cheltenham, achieved by March 1971.

However, a small team under Dr Shelley of the Special Horological Products Unit continued the development of a cutting-edge quartz watch – the Quasar – launched at the Basle Fair in 1973.

A few hundred pre-production watches were produced. The senior Smiths staff tested them, and when I interviewed some of them ten years ago, a few were recovered from bottom drawers.

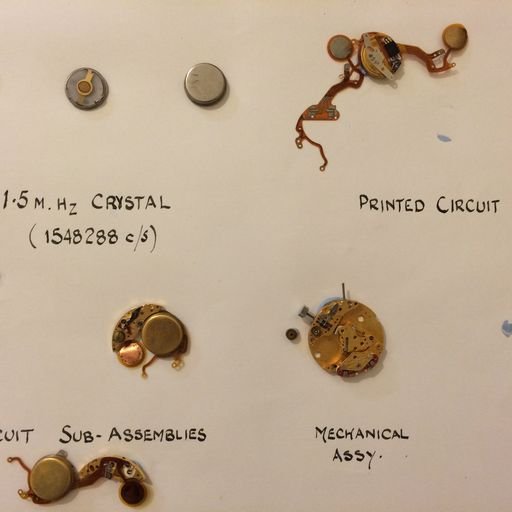

One of them was donated and is now in the Clockmakers' Company collection. Through similar generosity, the Clockmakers received a second watch, and also ephemera, including a rough card mounted with parts of the Quasar assembly.

Smiths used an AT-cut quartz crystal, not the normal XY cut. It resonated at 1.5 MHz, against the standard 32,768 Hz, and Smiths actually made this in-house, targeting high performance.

But this came at a price, in size, leaving little room for frequency division. Indeed, ‘conquering the division problem’ was the main achievement remembered years later by former senior Smiths managers.

Omega made a success of their 2.4 MHz AT-crystal watch, but bar or tuning-fork crystals of much lower frequency would soon dominate the mass market in watches by Timex and Junghans. Importantly, Seiko’s 38 Series watches had a frequency of 16,384, achieving better accuracy than the Quasar, with a frequency one hundred times lower!

Volume production of the Quasar never started – Smiths had stacked the odds against itself.

There were problems with the US supply of circuit boards, the stepper motors were hand-wound in Cheltenham, and in-house manufacture of the crystal was both expensive and inefficient.

Pricing was to be pitched at £70 in late 1973, but while watches were still being tested on the wrists of senior management, the chairman and MD of Smiths visited Seiko’s factories, and what they saw convinced them to pull the plug on the Quasar.

Until fairly recently, Quasars had remained essentially invisible – almost mythical. But at a remote auction, a Cheltenham watchmaker's effects turned up. Even if Smiths stopped work in 1973 or so, at least one person kept testing the pre-production samples.

Tags record watch 485 with crystal 419, and watch 365 with crystal 365, faults being found, and adjustments being made.

While the fossil record retains little evidence of a watch that never made it to market, some evidence of its development has nevertheless been preserved.