The AHS Blog

Ringing in the New Year

This post was written by Andrew Strangeway

As a clockmaker, or practising horologist, there is one particular moment while waiting for a clock to strike when time seems to slow down.This moment is more daunting when the streets outside are lined with 100,000 people and millions more are watching live on television, and streaming, waiting to hear the clock chime.

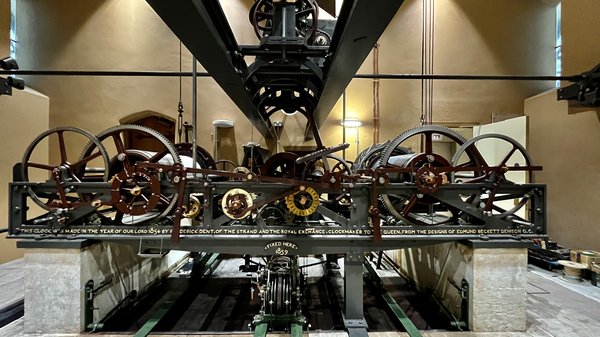

On December 31st it all comes down to a single moment, when the nation watches and waits for Big Ben to ring out and signal the start of the new year. Behind the scenes, however, months of preparation go into ensuring that this first hammer-blow falls precisely on time. Besides the installation of additional broadcast equipment, regular servicing, and thrice weekly winding there is also timekeeping: ensuring, literally, that the clock stays on time.

In the months leading up to the end of 2023, the timekeeping of the Great Clock was a core focus. After the break of six years during the servicing of the clock and tower, the twice-daily live chimes finally returned to BBC radio airwaves on November 6th. This New Year marked the 100th anniversary since the bells were first broadcast live for New Year’s Eve. It was a matter of pride that the clock should perform well and strike on time.

When it was first installed, the Great Clock was, by some margin, one of the most accurate public clocks in the world. The original specification for the clock set down in 1846 by George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, required that ‘the striking machinery be so arranged that the first blow for each hour shall be accurate to a second of time’. As clockmakers our job is to ensure that the clock remains true to this original purpose. To our advantage, we have highly accurate timekeepers to compare the Great Clock against and, armed with this information, we can regulate the pendulum carefully and actually comfortably exceed the original target for accuracy.

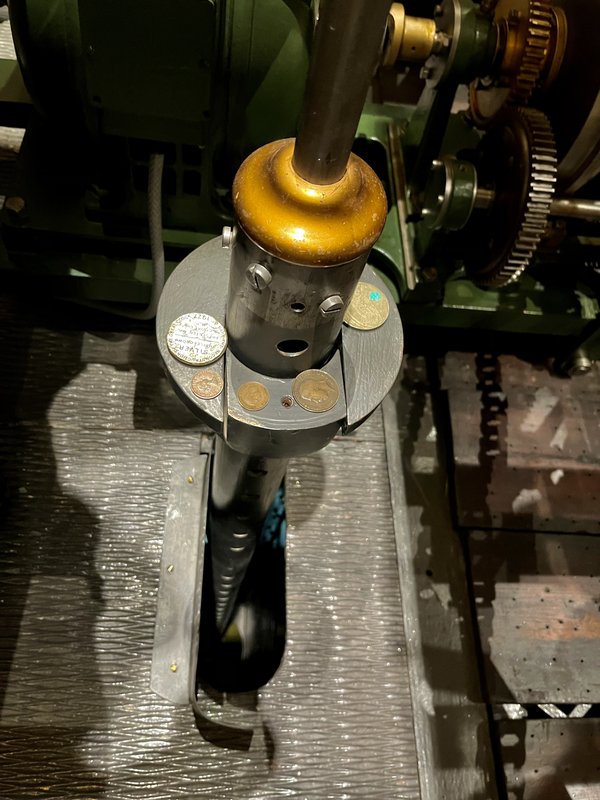

Since starting at the Palace of Westminster in August 2023, I have implemented the use of a new custom-made timer to increase the accuracy of the timing of the first hammer-blow of the hour and an improved regimen of regulating the rate of the clock’s pendulum. The core mechanics of regulation remains as ever: the placing or removing of weights, in the form of old currency, on a small platform partway down the length of the pendulum rod. Famously, one pre-decimal penny added speeds up the clock by about 2/5th of a second over 24 hours. These are a little too weighty and the adjustment too coarse if one is aiming for a finer degree of accuracy. I have begun using ha’pennies and farthings for regulation, kindly lent for the purpose by my colleague in the clock team, Ian Westworth. These speed the clock up by about a quarter of a second a day and a tenth of a second a day respectively.

In the final days running up to New Year’s Eve I was at the top of the tower, on the hour, throughout the day to take a timing reading from the strike and to make small adjustments to bring the clock precisely to time. As luck would have it, on the evening of the 30th we experienced heavy winds, which buffeted the tower and were enough to throw the clock out by 0.2 seconds by the morning of New Year’s Eve. I was able to correct for this by the evening. Midnight came and Big Ben struck, and the view of the fireworks from the top of the Elizabeth Tower was astounding. It was awesome to see the fireworks perfectly synchronised with the strike of the bell.

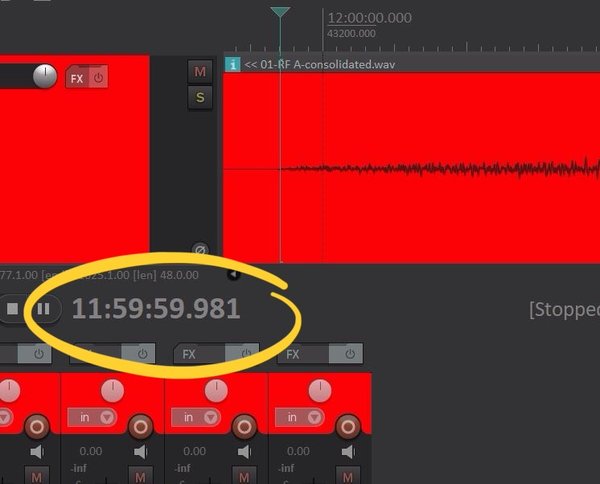

My timekeeping efforts were rewarded when we measured the timing of the strike from the sound recording compared with a GPS clock – these results were generously provided by Mark Powell of DeltaLive. The result was that Big Ben struck midnight at exactly 23:59:59.981, within less than a fiftieth of a second of midnight. That’s less than a fifth of the time it takes to blink your eyes. I must confess to being rather pleased with that!

The AHS 2015 Annual Meeting

This post was written by David Rooney

We welcomed over 100 members and guests to a packed full house at the National Maritime Museum for our 2015 Annual Meeting last Saturday. The sun shone, the atmosphere was buzzing, and we were given a superb day of talks and conversation.

The theme this year was ‘time and transport’ and, outside the museum, AHS members had brought a stunning selection of vintage cars to help set the scene.

During the morning session, we had fascinating talks by Peter Burt on RGS explorers’ watches; Tabea Rude and Erika Jones on zig-zag control; and Rory McEvoy on a Perregaux advertising campaign (apologies for the poor quality indoor photographs!)

After lunch and the society’s AGM, we heard from our new President, Lisa Jardine, on sea-going clocks; Jonathan Betts on polar expedition chronometers; and James Nye on the history of car clocks.

We were delighted to learn that Professor Jardine has recently been made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society.

We also marked the handover of the chairing of the society from David Thompson to James Nye by seeing David awarded a Fellowship of the AHS. Our huge congratulations and thanks to Lisa, David and James.

It was great to see so many members and guests from all around the country, of all ages and with all sorts of interests—represented also in the wonderful variety of speakers and lectures.

Thanks to you all for coming—and we look forward to the coming year with great excitement!

A second in one-hundred days: insanity or genius?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In 1775 John Harrison made a critical remark about Graham’s dead beat escapement, saying, of George Graham, that '…either he must be out of his Senses, or I must be so!'

Later in the same publication he stated of his own clock that '…there must be then more reason…that it shall perform to a second in 100 days…than that Mr Graham’s should perform to a second in 1.'

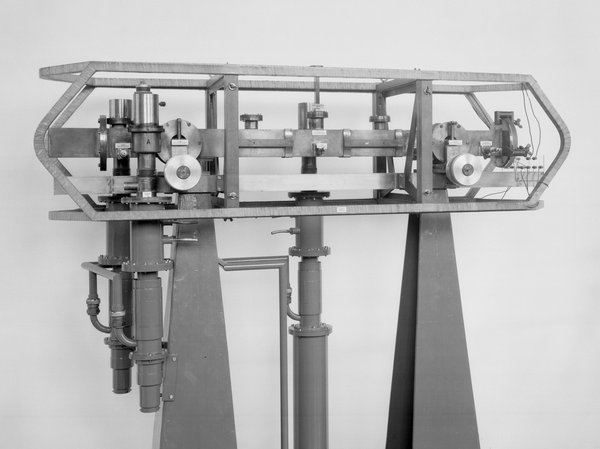

Keeping time consistently to within one second in 100 days was a degree of accuracy not achieved until around a century and a half later by mechanical clocks such as Shortt’s free pendulum system.

Harrison published his remarks in a vitriolic and virtually impenetrable book, the manuscript and transcriptions of which are freely accessible online.

On reading the book, which contains scattered descriptions of his method, the celebrated watchmaker Thomas Mudge, stated of Harrison that the book’s contents had '…lessened him very much in my esteem…' and that '…there are several things which he says about Mr Graham’s pallets and pendulum that are absolutely false…'.

The London Review of English and Foreign Literature described the work as 'one of the most unaccountable productions we ever met with' and went on to say that 'every page of this performance bears marks of incoherence and absurdity, little short of the symptoms of insanity'.

Harrison’s words were not taken seriously by any of his contemporaries and his radical statement about the capabilities of his pendulum clock, with its large pendulum arc, relatively light bob, and recoil grasshopper escapement, remained largely unexplored until the 20th century.

Then, in 1977, a number of horological scholars, who became known as The Harrison Research Group, began to look at his theories afresh.

Martin Burgess’ Clock B is a product of this collaborative research and represents one of the most significant historio-technical investigations in recent years. Recently, numerous experiments have been tried on the clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with exciting results.

To learn more about this intriguing project please join us for a special one-day conference on July 12 2014 at the NMM.

The AHS Annual Meeting 2014

This post was written by David Rooney

On Saturday 17 May, 120 AHS members and guests packed into the National Maritime Museum’s lecture theatre for our 2014 Annual Meeting. It was a sell-out crowd, and what a day we all enjoyed.

Those who couldn’t make it missed a couple of important announcements which I’ll pass on here in advance of them appearing in the next Antiquarian Horology .

The first announcement came from Sir Arnold Wolfendale, the 14th Astronomer Royal, who has been a tireless supporter and champion of the AHS since becoming our President over 20 years ago.

Sir Arnold, whose inspiring and lively lectures on cosmological aspects of timekeeping have been enjoyed by so many of us over the years, has decided to stand down. We wish to thank him hugely for all of his support over the years and wish him well in his ‘retirement’ from the presidency.

David Thompson then announced that Professor Lisa Jardine, the eminent historian, writer and broadcaster, has agreed to become our new President, and takes over immediately.

Lisa is teaching this term at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (home of the recent Time For Everyone symposium), and could not be present in person, but she sent her best wishes and looks forward to meeting us in person in the near future.

We are delighted and honoured to welcome Lisa to the AHS presidency.

The other major announcement of the day was the launch of the brand new AHS website. We urge you to take a look. It is the culmination of many months of patient work by a small AHS team plus our designers, Latitude, and our web developers, Blanc, and has been fully funded by a donation from council member James Nye.

At the heart of the website is a remarkable new resource for AHS members. We have digitized the entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, and every single page we have ever published, dating back to the first issue in 1953, is now available and searchable online.

We are thrilled to bring this invaluable resource to members and wish to thank our great friends and technology partners, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in Germany, for carrying out the scanning and indexing work at an extremely preferential rate.

You can find the new website at our usual address, www.ahsoc.org, and to use the digital journal, simply log in to the members pages with the password printed on the back of your AHS membership card.

The addition of the journal archive is an extremely valuable new member benefit which must surely be worth the AHS subscription alone, so do please encourage your friends, colleagues and clients to join (don’t forget that you can join online using credit cards, debit cards or PayPal in just a few easy and secure clicks).

A tiny housekeeping note. The AHS blog on which you are reading this post has now moved to blog.ahsoc.org. The old address will still work fine, but if you subscribed to posts using an RSS feeder, we’re afraid you’ll need to re-subscribe from the new location. Sorry about that.

There’s never been a better time for reform!

This post was written by James Nye

A gauntlet has been laid down. Across Europe, thoughtful people are busy working up ingenious ideas for a competition devised over an extraordinary April weekend in southern Germany.

Each year, several dozen of the electro-horo-cognoscenti gather in Mannheim-Seckenheim for an event organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven.

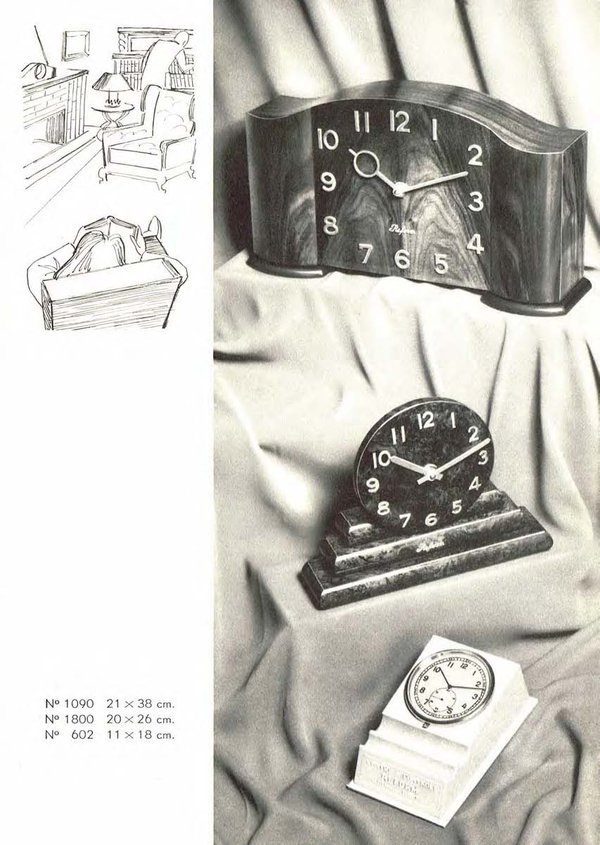

The fifteenth of these gatherings—a combination of market, lectures and much eating, drinking and good conversation—saw a new visitor who brought many interesting items, not least several hundred new-old-stock Reform movements, tissue-wrapped and boxed.

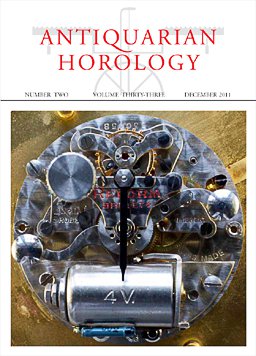

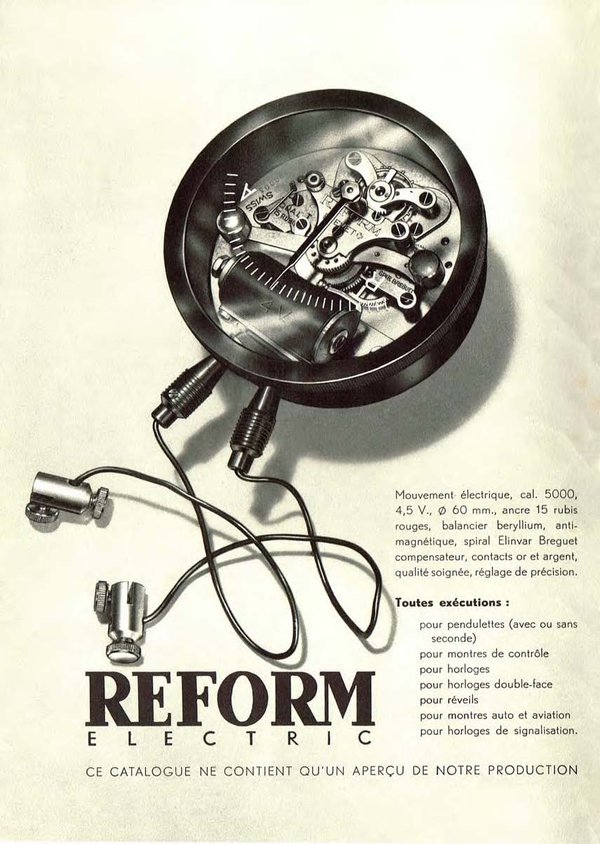

Alert readers will recall an Antiquarian Horology cover featuring a classic example of the Reform calibre 5000 movement, and a fascinating accompanying article.

As David Read comments, these Schild movements are ‘without doubt the best known and most commercially successful of all the many varieties of electrically-rewound clock movements’ from the 1920s onwards. The calibre 5000 is a lovely object, jewelled, with damascened plates, and micrometer regulation.

Nye’s theorem proposes that hi=as*bc/ebw where hi stands for horological inventiveness, as represents afternoon hours of sunshine, bc denotes beers consumed and ebw stands for evening bottles of wine.

With a lively group, talk over two sunny days and late evenings turned to possible creative uses for virgin Reform movements.

Given their looks, the mechanism must remain visible, but the motion work is to the (unremarkable) reverse. This led to discussions of projection clocks, or elaborate gearing to present time in the same plane as the movement, but to one side.

There was even intriguing talk of a large scale tourbillon. More detail than this presently remains closely held, but a competition to determine the best use was announced, to be decided in Mannheim in April 2015.

Reform is the order of the day.

A million free images

This post was written by David Rooney

Just before Christmas, the British Library released over a million historical images from its printed collections onto the image-sharing website Flickr. The images are out of copyright and the library has made them available with a Creative Commons licence which, in short, encourages anybody to use, remix and repurpose them, so long as they respect a few ground rules.

This is a remarkable resource of imagery and will be a boon for anybody carrying out historical research – such as AHS members.

There are countless images of interest in this release, each one of which might augment an existing research project or prompt a new one. The beauty of archives such as this is the opportunity for lateral thinking. You might be researching a particular village, or writer, or building, or period. And you might find an image here that opens up new avenues of research.

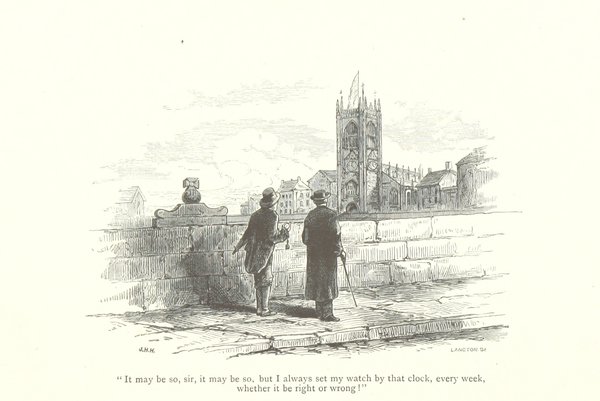

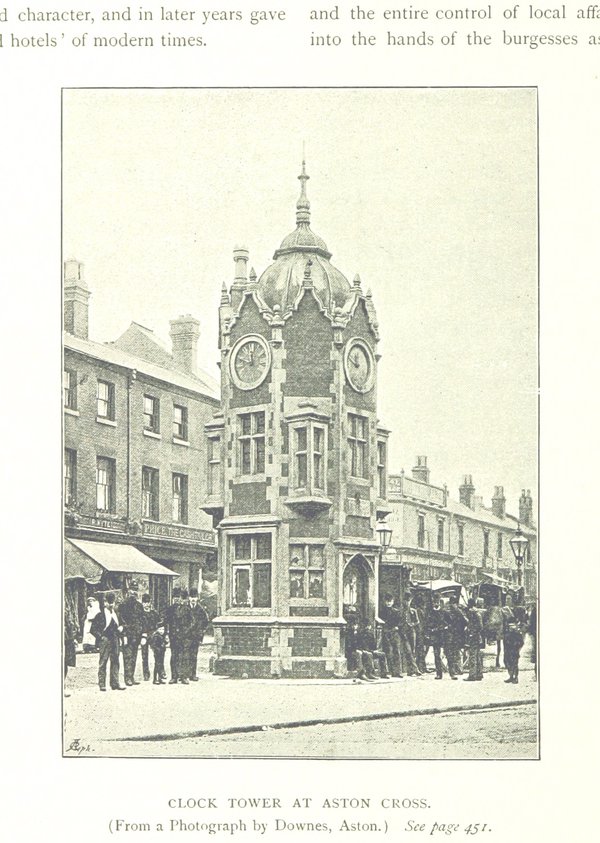

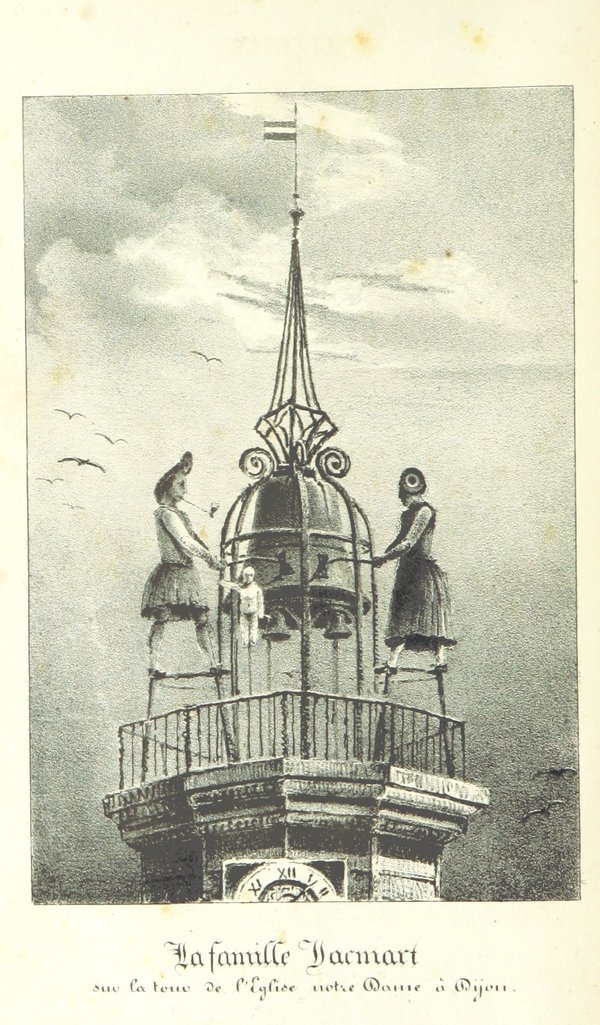

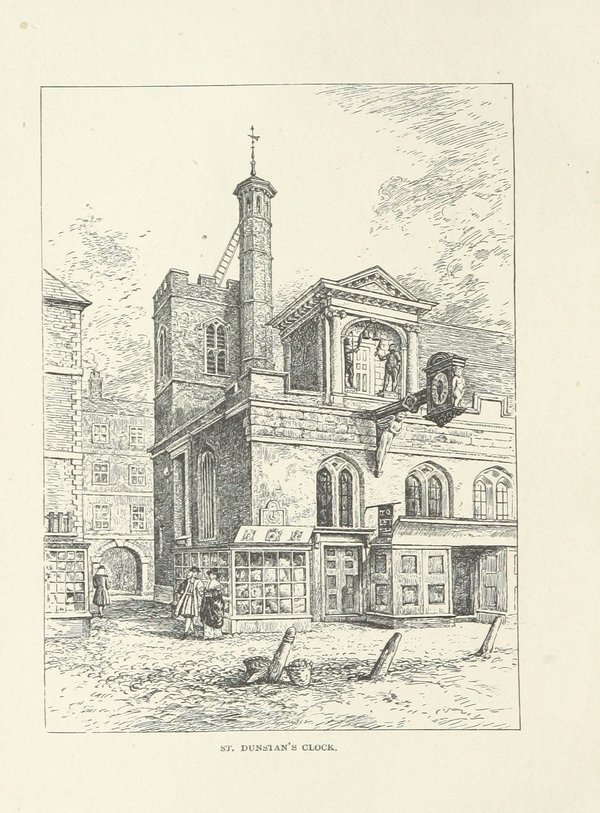

The first four images I found are the result of searching for ‘clock’ or ‘clocktower’ – as you’d expect, lots of public clocks.

But let’s say I’m interested in chronometers. Unfortunately there are no search returns for that word. But then I tried searching for ‘observatory’, and found this image.

It’s from a book on the North Polar Expedition, and it’s a photograph of marine chronometers on show in a US Navy centennial exhibit in 1876.

That led me to this catalogue of the objects exhibited. And on pages 79–81 there’s a remarkable and detailed description of the use of chronometers at the US Naval Observatory in the 1870s. Serendipitous discovery is a wonderful thing.

You’ll probably want to put aside an hour or two browsing these images – and a lot more time following the interesting leads they throw up! Happy hunting, and happy new year.

Home time

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

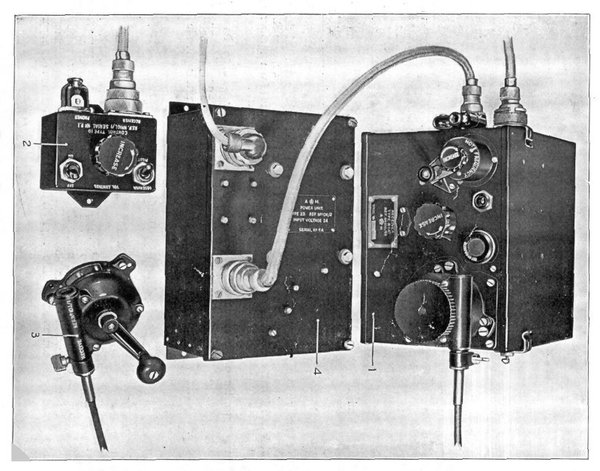

As next year’s AHS conference will be shaped by the theme ‘Military Time’, it seems appropriate that this post should follow the military theme and by chance, as with David Read’s recent post, it includes a radio.

There are two HS.4 navigational watches in the National Maritime Museum collection, both retailed by the firm H. Golay and Sons, which were used by the Fleet Air Arm in Fairey Swordfish aircraft during WWII.

We learn from the 1941/1942 Admiralty Manual of Navigation that these watches were known as beacon watches and that they were only to be used in aircraft fitted with an R1147 radio receiver.

The carriers were equipped with a revolving beacon that continuously transmitted second pulses, making a full rotation once per minute. The crucial feature of this system was that the beacon emitted a different sounding signal when it was pointing due north. Prior to launch (these planes were catapulted into the air) the observer would tune the radio receiver to the beacon and set the bezel of the watch so that zero on the outer scale and the tip of the second hand align precisely at the time of the northern signal.

When returning to the carrier, the observer on board the aircraft would turn on the radio and listen to the beacon’s signal. The strongest reception would be experienced when the beacon was pointing directly at the aircraft and using the watch, the aircraft’s position relative to its carrier could be found and the pilot given the course to take.

If we take the watch shown above, for example, as indicating the moment of the signal’s maximum intensity, the aircraft’s position would be approximately SSW of the carrier. The primary benefit was that these slow aircraft could home in on their carrier from up to 100 miles away without sending out radio signals that may betray their position to the enemy.

This ingenious horological adaptation helped to save lives and is just one example of innovation necessitated by war that could be explored at next year’s conference.

If you feel that you can contribute a talk that would fit ‘Military Time’ theme, you are invited to contact the AGM lecture coordinator, Rory McEvoy, Curator of Horology, Royal Observatory Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SE10 9NF, e-mail: RmcEvoy@rmg.co.uk. Papers could explore technical horological development as well the wider implications for both civil and military timekeeping. Please note that the theme is not limited to the First World War, and that the military of course includes the ground, sea and air forces.

Decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation

This post was written by David Rooney

I spend quite a lot of time thinking about leap seconds. They’re the extra seconds inserted into time at midnight on New Year’s Eve every few years.

Recently they’ve been hitting the news, as a proposal led by some American time scientists to abolish the leap second system has caused a bit of a furore.

OK, here’s the deal. For ever, we’ve measured time by the rotation of the Earth. One rotation equals one day. At least, that was the case until Louis Essen and Jack Parry developed the first practical atomic clock, in 1955 (you can see it at the Science Museum).

This technology, once developed and refined, became a more accurate timekeeper than the spinning Earth, so we moved to atomic clocks to measure time.

But we’re animals, and we’re therefore hard-wired to the temporal patterns of the Earth’s rotation – daylight and darkness, the seasons. So a system was designed to keep the new atomic timescale in step with the Earth.

That’s the leap second, and we’ve been recalibrating the atomic clocks with these occasional one-second corrections since 1972. The resulting timescale is called Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC, and it’s never more than a fraction of a second away from Greenwich Mean Time.

So the proposal by the American scientists to abolish the leap second system and let our civil timescale drift away from GMT has set a lot of people thinking about fundamental issues in the philosophy, technology and metrology of timekeeping.

My point? Recently I read about a colloquium held last October in Pennsylvania exploring the implications of redefining UTC as a purely atomic timescale – decoupling civil timekeeping from Earth rotation.

You can read the papers and discussions here (click Preprints). This is truly fascinating stuff – measured, thoughtful and far-reaching, and the first substantial engagement I have read on the implications of this challenging proposal. Well worth a read if you’ve a spare second.

Don’t forget David Thompson’s lecture next week

This post was written by David Rooney

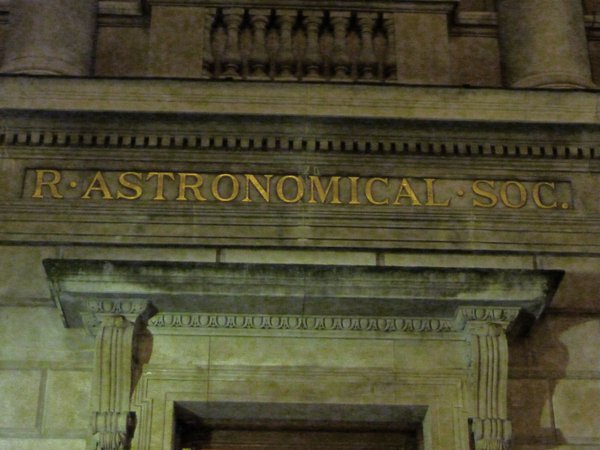

If you came to the AHS inaugural event at the Royal Astronomical Society in January, you’ll know our new venue in Burlington House makes for a superb evening’s entertainment – and it’s free.

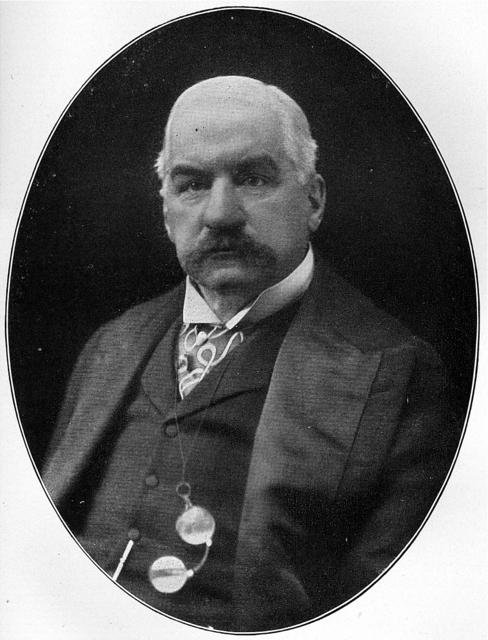

Our second event is next week, so mark it in your diaries now. On Thursday 15 March, AHS Chairman and British Museum curator David Thompson will give the next in our series of talks on ‘The Great Collectors’. This time it’s all about the industrialist, financier and banker, J. P. Morgan.

Whilst Morgan’s business interests are well known, it is his collecting activity that will be in the spotlight on Thursday. Best remembered as a collector of art, gemstones and rare books, he also amassed a considerable number of clocks and watches, concentrating on 16th to 18th century decorative pieces.

This talk promises to provide a sumptuous insight into Morgan’s horological treasures, which David will compare against similar material in other collections. For anybody interested in watches, clocks and the mind of the collector, this will be an evening to remember.

Doors will open at 5.30pm for tea with the talk beginning at 6.15pm. There will be a drinks reception afterwards in the Library. Nearest tube stations are Green Park and Piccadilly Circus.

Thanks to the generous sponsorship of The Clockworks , the event is free – but if you would like to make a contribution to support the work of the AHS further, please do get in touch. We’d love to hear from you.

First AHS event at Burlington House

This post was written by David Rooney

Our 2012 London Lecture Series kicked off in style last week, when over 100 AHS members and friends flocked to the Royal Astronomical Society at Burlington House, Piccadilly, for the inaugural event at our new venue.

This special event saw our usual single bi-monthly lecture replaced by a series of speakers offering reflections on objects and ideas in the story of time.

Sir Arnold Wolfendale, astronomer and AHS president, welcomed the society to the RAS, whilst founder member Michael Hurst surveyed our achievements since 1953. Chairman David Thompson looked forward to the coming year, then introduced a further six speakers, each assessing different aspects of the society’s interests.

Jonathan Betts explored the study of domestic clocks, followed by David Penney considering issues in pocket and wristwatch history. Matthew Read offered a vision of the society’s role in conservation and material research, whilst Keith Scobie-Youngs outlined the challenges and opportunities offered by turret clocks. James Nye gave a sparkling presentation of the electric timekeeping group’s achievements over four decades, and the talks concluded with Andrew King assessing opportunities for future research.

The event proved exceptionally popular, with all tickets allocated well in advance and additional space being provided in the RAS council room, linked by video to the lecture theatre.

The talks were followed by a champagne reception generously sponsored by The Clockworks, a new gallery, conservation workshop, library and meeting space dedicated to electric timekeeping, launching in London later this year.

Our next London lecture will be held on 15 March, when David Thompson continues our series of talks on the great clock and watch collectors. It promises to be an enlightening event – look forward to seeing you there.