The AHS Blog

Keeping in touch with time

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

A common feature of watches and clocks of the 16th century are touch-pins. These are raised studs located at each hour position on the dial, with that at the 12 o’clock position typically being longer and sharper to provide a point of reference.

These enable the time to be read by feeling the position of the single, robust, hour hand.

This was useful as it was not possible to simply switch on a lamp to read the time at night. An added benefit might have been that the time could be read discretely under one’s robes.

This is a later variation of touch indication, known as a “montre à tact” (“touch watch”).

The exposed hand does not turn with the movement but it is moved manually, clockwise, until it stops at the right time. This is read against touch-pins that are located on the edge of the case.

These watches are also sometimes known as “blind-man’s” watches but, although they could have served as such, they were conceived as night watches.

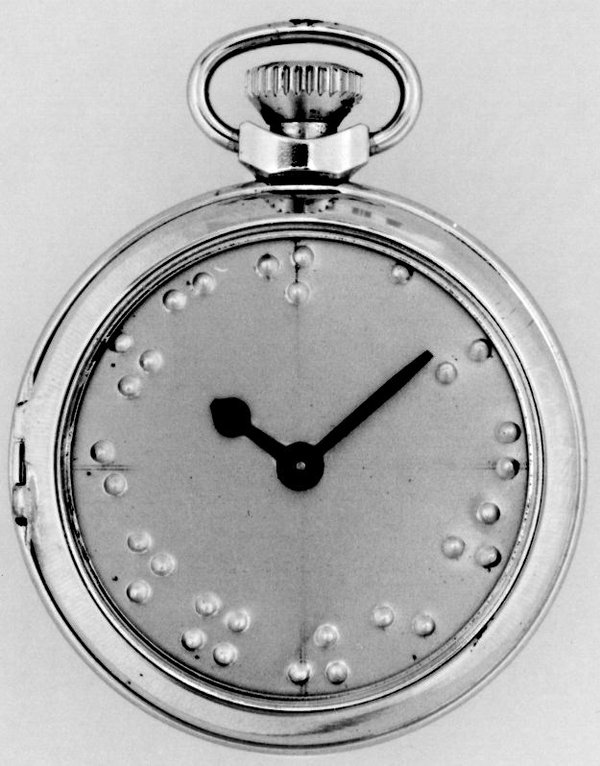

This watch, however, was clearly designed to be used by visually impaired persons as it has Braille numerals on the dial.

Mass production of watches and clocks became established in the 19 th century and it enabled them to be affordable to the masses and, subsequently, the massive new market enabled a much greater variety to be economically viable, including this Braille watch.

This wrist-watch bears the latest incarnation of touch indication.

The time is indicated by steel ball bearings which run in tracks, positioned by magnets driven by the movement within the case – the hours around the perimeter and the minutes on the front of the watch.

The balls are easily displaced, which prevents damage to the movement, but are easily relocated with a twist of the wrist.

The watch was conceived for use by visually impaired persons, but its elegant design appeals to a far larger market. The development of this watch somewhat parallels that of the Braille watch, as it also depended on a fundamental development in technology and economics.

This watch was brought to market through internet “crowd-funding”, whereby many individuals invest a relatively small amount each to raise the total capital necessary to fund the development of a product (in this case enabled by Kickstarter). Crowd-funding can enable some exciting projects to succeed which might have been rejected by more traditional investors.

A second in one-hundred days: insanity or genius?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In 1775 John Harrison made a critical remark about Graham’s dead beat escapement, saying, of George Graham, that '…either he must be out of his Senses, or I must be so!'

Later in the same publication he stated of his own clock that '…there must be then more reason…that it shall perform to a second in 100 days…than that Mr Graham’s should perform to a second in 1.'

Keeping time consistently to within one second in 100 days was a degree of accuracy not achieved until around a century and a half later by mechanical clocks such as Shortt’s free pendulum system.

Harrison published his remarks in a vitriolic and virtually impenetrable book, the manuscript and transcriptions of which are freely accessible online.

On reading the book, which contains scattered descriptions of his method, the celebrated watchmaker Thomas Mudge, stated of Harrison that the book’s contents had '…lessened him very much in my esteem…' and that '…there are several things which he says about Mr Graham’s pallets and pendulum that are absolutely false…'.

The London Review of English and Foreign Literature described the work as 'one of the most unaccountable productions we ever met with' and went on to say that 'every page of this performance bears marks of incoherence and absurdity, little short of the symptoms of insanity'.

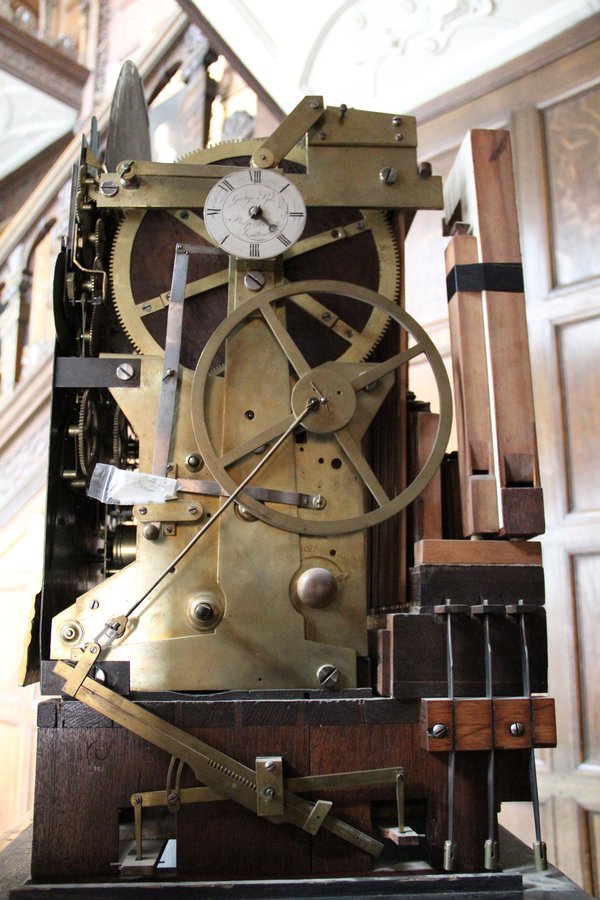

Harrison’s words were not taken seriously by any of his contemporaries and his radical statement about the capabilities of his pendulum clock, with its large pendulum arc, relatively light bob, and recoil grasshopper escapement, remained largely unexplored until the 20th century.

Then, in 1977, a number of horological scholars, who became known as The Harrison Research Group, began to look at his theories afresh.

Martin Burgess’ Clock B is a product of this collaborative research and represents one of the most significant historio-technical investigations in recent years. Recently, numerous experiments have been tried on the clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with exciting results.

To learn more about this intriguing project please join us for a special one-day conference on July 12 2014 at the NMM.

The AHS Annual Meeting 2014

This post was written by David Rooney

On Saturday 17 May, 120 AHS members and guests packed into the National Maritime Museum’s lecture theatre for our 2014 Annual Meeting. It was a sell-out crowd, and what a day we all enjoyed.

Those who couldn’t make it missed a couple of important announcements which I’ll pass on here in advance of them appearing in the next Antiquarian Horology .

The first announcement came from Sir Arnold Wolfendale, the 14th Astronomer Royal, who has been a tireless supporter and champion of the AHS since becoming our President over 20 years ago.

Sir Arnold, whose inspiring and lively lectures on cosmological aspects of timekeeping have been enjoyed by so many of us over the years, has decided to stand down. We wish to thank him hugely for all of his support over the years and wish him well in his ‘retirement’ from the presidency.

David Thompson then announced that Professor Lisa Jardine, the eminent historian, writer and broadcaster, has agreed to become our new President, and takes over immediately.

Lisa is teaching this term at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (home of the recent Time For Everyone symposium), and could not be present in person, but she sent her best wishes and looks forward to meeting us in person in the near future.

We are delighted and honoured to welcome Lisa to the AHS presidency.

The other major announcement of the day was the launch of the brand new AHS website. We urge you to take a look. It is the culmination of many months of patient work by a small AHS team plus our designers, Latitude, and our web developers, Blanc, and has been fully funded by a donation from council member James Nye.

At the heart of the website is a remarkable new resource for AHS members. We have digitized the entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, and every single page we have ever published, dating back to the first issue in 1953, is now available and searchable online.

We are thrilled to bring this invaluable resource to members and wish to thank our great friends and technology partners, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in Germany, for carrying out the scanning and indexing work at an extremely preferential rate.

You can find the new website at our usual address, www.ahsoc.org, and to use the digital journal, simply log in to the members pages with the password printed on the back of your AHS membership card.

The addition of the journal archive is an extremely valuable new member benefit which must surely be worth the AHS subscription alone, so do please encourage your friends, colleagues and clients to join (don’t forget that you can join online using credit cards, debit cards or PayPal in just a few easy and secure clicks).

A tiny housekeeping note. The AHS blog on which you are reading this post has now moved to blog.ahsoc.org. The old address will still work fine, but if you subscribed to posts using an RSS feeder, we’re afraid you’ll need to re-subscribe from the new location. Sorry about that.

There’s never been a better time for reform!

This post was written by James Nye

A gauntlet has been laid down. Across Europe, thoughtful people are busy working up ingenious ideas for a competition devised over an extraordinary April weekend in southern Germany.

Each year, several dozen of the electro-horo-cognoscenti gather in Mannheim-Seckenheim for an event organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven.

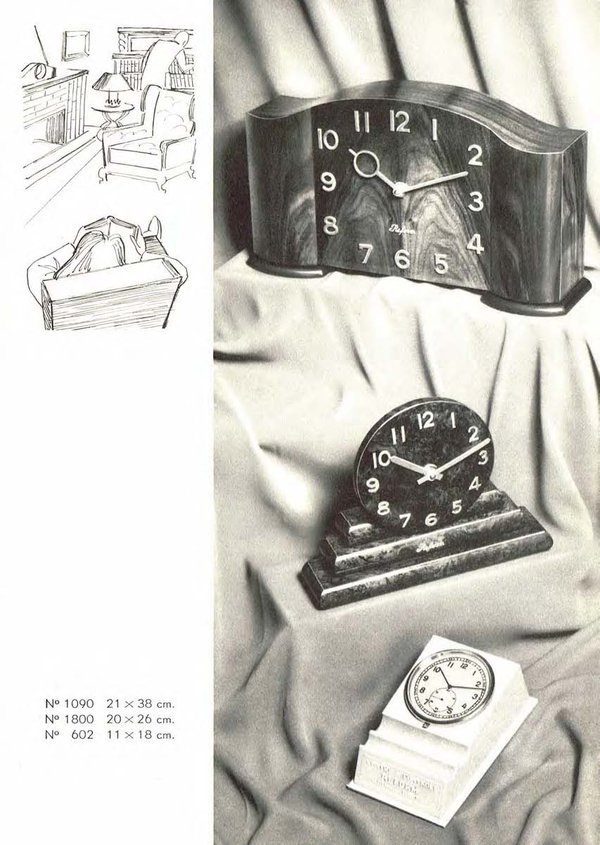

The fifteenth of these gatherings—a combination of market, lectures and much eating, drinking and good conversation—saw a new visitor who brought many interesting items, not least several hundred new-old-stock Reform movements, tissue-wrapped and boxed.

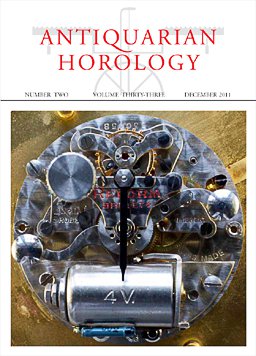

Alert readers will recall an Antiquarian Horology cover featuring a classic example of the Reform calibre 5000 movement, and a fascinating accompanying article.

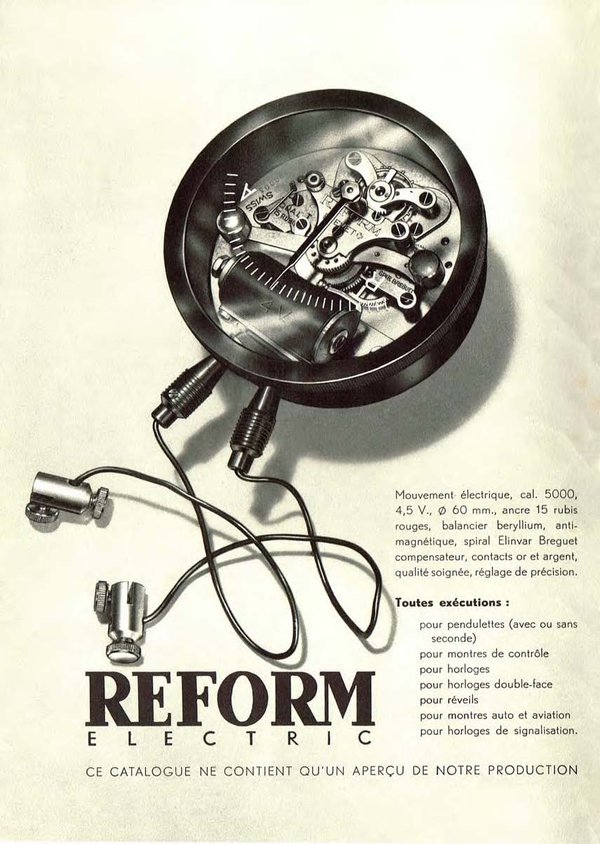

As David Read comments, these Schild movements are ‘without doubt the best known and most commercially successful of all the many varieties of electrically-rewound clock movements’ from the 1920s onwards. The calibre 5000 is a lovely object, jewelled, with damascened plates, and micrometer regulation.

Nye’s theorem proposes that hi=as*bc/ebw where hi stands for horological inventiveness, as represents afternoon hours of sunshine, bc denotes beers consumed and ebw stands for evening bottles of wine.

With a lively group, talk over two sunny days and late evenings turned to possible creative uses for virgin Reform movements.

Given their looks, the mechanism must remain visible, but the motion work is to the (unremarkable) reverse. This led to discussions of projection clocks, or elaborate gearing to present time in the same plane as the movement, but to one side.

There was even intriguing talk of a large scale tourbillon. More detail than this presently remains closely held, but a competition to determine the best use was announced, to be decided in Mannheim in April 2015.

Reform is the order of the day.

Of mice and clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In his most recent blog, Oliver Cooke discussed watches and clocks without hands as indicators.

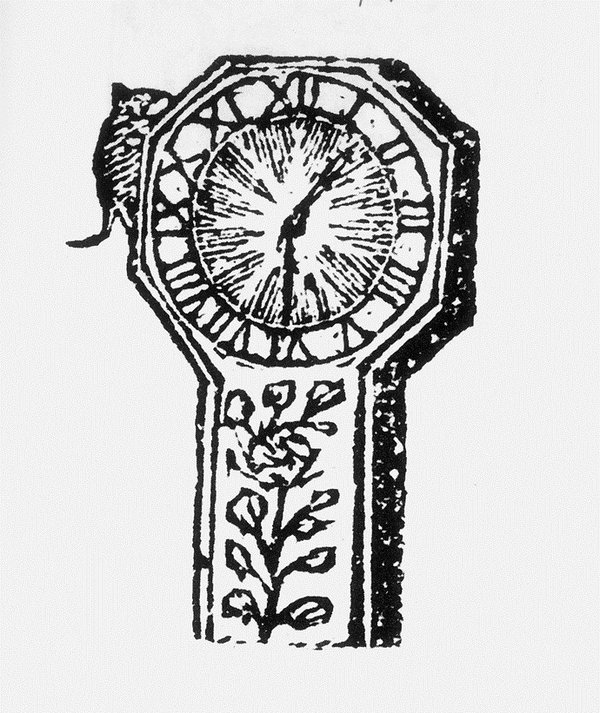

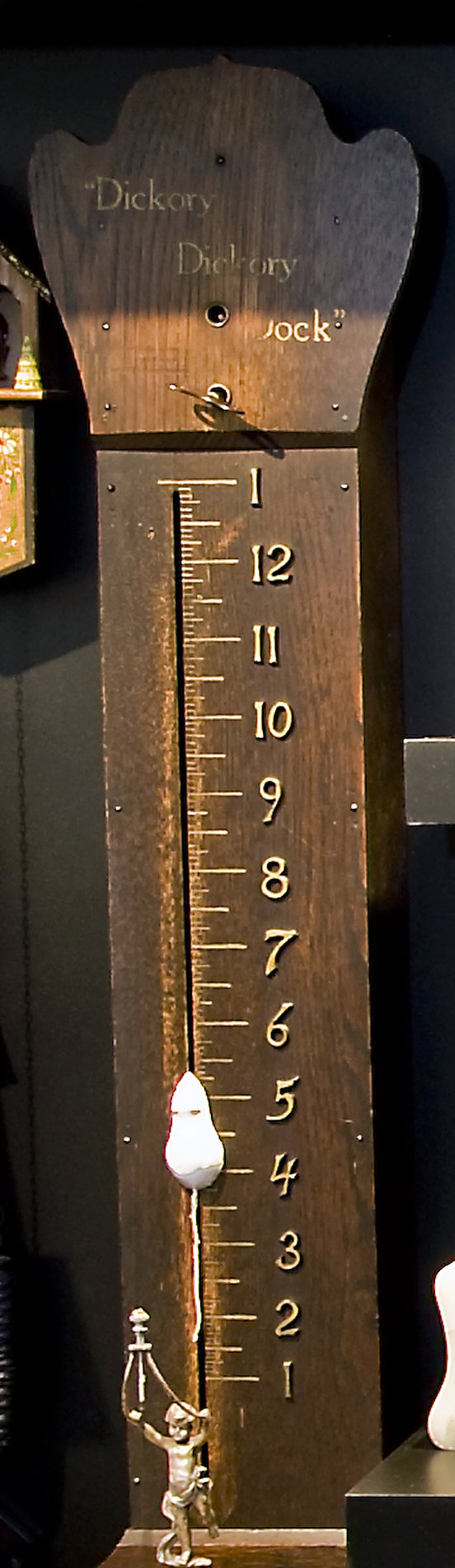

Another example is the Mouse Clock, in which a mouse making its way up against a wooden board serves as time indicator. Its designer was inspired by the well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickere, Dickere Dock

A Mouse ran up the Clock,

The Clock Struck One,

The Mouse fell down,

And Hickere Dickere Dock.

The rhyme comes in various versions; this is the oldest, published in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s_Pretty_Song_Book.

Could it be based on a real event: a mouse hiding inside a longcase clock, panicking when it struck?

In the literature I find only other explanations. One authority suggests it may be an onomatoplasm – an attempt to capture, in words, a sound; in this case, the sound of a ticking clock. Another relates it to the shepherds of Westmorland who once used ‘Hevera’ for ‘eight’, ‘Devera’ for ‘nine’ and ‘Dick’ for ‘ten’ when counting their flock.

Be that as it may, just over a century ago it inspired an American businessman, who was also an avid clock collector, named Elmer Ellsworth Dungan, to develop the Mouse Clock.

He initially just created one for his daughter, who loved the nursery rhyme, but then decided to take them into production. He took out patents and various models were manufactured.

They are nowadays prized by novelty clock collectors, so much so that we are warned to beware of reproductions, especially for what one dealer calls ‘Chinese knockoffs’.

Details, including several images of the mechanism, and a link to an animated photo of the clock in operation, can be found on these American websites: Antique Clock Guy and Fontaine’s Auction Gallery.

In 1966 the NAWCC published a booklet by Charles Terwilliger, Elmer Ellsworth Dungan and the Dickory, Dickory Dock Clock; there is a copy in the AHS Library at the Guildhall.

And speaking of mice and clocks, how about having some fun with the (grand)children with this on-line clock reading game. Read the time correctly and the mouse runs up safely to the cheese in the clock. Read it wrong and the cat gets the mouse.

British Pathé films on YouTube

This post was written by David Rooney

In the latest in what seems to have become a short series on easy-access digital resources, I bring news that British Pathé has released its entire historical newsreel archive of 85,000 films onto YouTube, the video-sharing website.

British Pathé has long allowed people to see its historical newsreel films on its own website, and the release to YouTube doesn’t bring any change to the company’s copyright policy. But the findability of these often remarkable films will now have greatly increased, which can only be a good thing.

I have used British Pathé films in my historical research and my professional work curating museum exhibitions for years now, and it is therefore like meeting old friends to watch films on the YouTube channel such as The Golden Voice, Time Please and Standard Time.

For those with wider interests, I’ve also been moved seeing Comet Inquiry again, which appeared in the Science Museum’s recent award-winning Alan Turing exhibition. One of the AHS’s founder members, Alfred Basil Brooks, together with his wife, were killed in this tragic air crash which occurred just months after the founding of the society.

I think this film archive is strong in two ways beyond its sheer breadth.

Firstly, it helps to put technological objects and ideas into social and political context, which is crucial in understanding why people make, modify, use and choose things. Objects never emerge fully-formed in a contextual vacuum.

The second strength of the films is the technical understanding they can offer those studying particular technologies. There’s nothing like the moving image to bring dynamic objects to life.

So there we are. Another great digital archive of work made even easier to use. And along those lines, AHS members should watch out for an important announcement in the next few weeks. We’ve been working on something pretty special and we’re about to be able to share it with you…

You can find the British Pathé channel at https://www.youtube.com/user/britishpathe. Search by clicking the little magnifying glass symbol in the middle of the page underneath the header image.

Time in Old Bohemia

This post was written by David Thompson

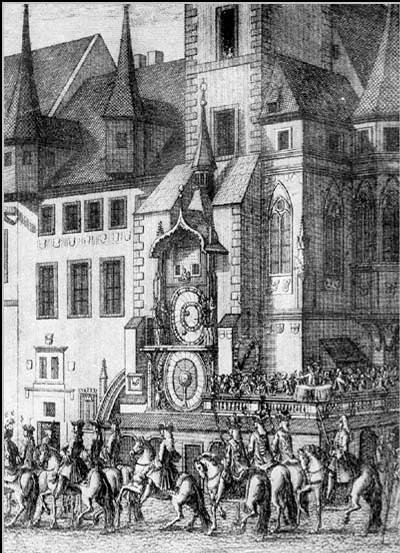

Many thousands of people today have stood amazed in front of the Astronomical Clock in the Old Town Hall Square in Prague, but I wonder just how many have managed to make sense of the dial. In modern times, perhaps it makes little sense.

The clock was made by Jan Šindel in about 1410, and from as early as the 15th century, the clock had a 24 hour dial which showed the so-called Bohemian Hours, a system in which the day began and ended at sunset.

This means, of course, that the 24-hour ring around the outside had to be adjusted periodically so that the 24th hour coincided with sunset.

In the early part of the clock’s life this was done manually, but later an automatic mechanism was installed to adjust the position of the ring. In medieval Prague, a knowledge of how long it was to sunset and the imposition of curfews in the city was useful knowledge. For instance – a simple glance at the dial indicating 19 hours tells you straight away that it is five hours to go before sunset.

As well as telling the time, the dial also has moving sun and moving effigies of the sun and moon, showing where in the zodiac they lie throughout the year. Useful astrological information.

The ecliptic circle with the zodiac signs and the sun and moon effigies rotate together once per day, but gradually over the course of the year, the sun and moon effigies with make a complete circle of the zodiac.

All this is achieved by some sophisticated gearing located behind the dial and driven by the clock mechanism in the tower. With the horizon circle with shaded buff areas, the periods of Aurora and Crepuscular, dawn and dusk are also shown,

Today, the clock is controlled by a more modern ‘regulator clock made by Romuald Bozek in the 1860s, but for the most part, the clock mechanism is still that which has been in existence from the beginning of its history.

Looking at the illustration here, you will see that the time is just a few minutes past 13 hours. On the fixed chapter circle the time is shown just before IX o’clock in the morning and hour 24 is just before 8 o’clock in the evening – correct for a July date. The sun is in Leo and the moon is in Aries.

So next time you stand in front of this amazing clock, you can really show off by knowing how to read the dial.

Look no hands!

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have looked at single-handed dials, on the other hand we have looked at some more unusual forms of indicator. Here we will look at indicators with no hands at all.

This watch has a display with digits formed of light emitting diode (LED) segments, seven for each numeral.

LED watches were first introduced in 1970 by the Hamilton Watch Company and were soon followed by liquid crystal display (LCD) watches. LED and LCD were by no means the first technology to enable digital displays however.

Before these examples existed the 'wandering hour' dial, something of a mash-up of digital and analogue time indication.

The hour numeral wanders, from the left-hand position (as viewed), up-and-over the semicircular aperture during the course of an hour. As the current hour ends and disappears behind the dial plate, the next hour numeral appears on the left.

We see 12:14 indicated on the illustrated example.

The system was invented in the 1650s by the brothers Tomasso and Matteo Campani from San Felice in Umbria, as a means to enable the time to be read at night (the numerals are pierced, allowing the light of an oil lamp to pass through from behind). This was very useful in the days before instant electrical lighting.

The wandering hour dial was also, occasionally, used on watches in the late 17th century, (but an oil lamp was not fitted in these!)

Finally, this watch also blurs the distinction between analogue and digital.

It has an LCD but, instead of digits, it has radial segments representing hands. This, however, requires 120 segments instead of the 42 needed to make up a standard six-digit digital display.

Together with the corresponding electronics needed to drive each segment, this means that these “LCA” watches cannot be made as cheaply as their digital counterparts. Perhaps for this reason they have never been popular, but they must have an adequate, if small, number of fans as they seem to have always (just) remained in continous production by one manufacturer or another since the 1970s.

I wonder how many of their fans, like I, appreciate them mostly for the futility of over-engineering, to achieve a result with LCD that is much more easily and better obtained with physical hands!

Clock world full of cranks?

This post was written by James Nye

Things turn up. Back in 2006, when David Rooney and I were researching the Standard Time Company (STC), we planned a lecture at the Guildhall library.

The only surviving early clock we knew of had spent its life at the Royal Observatory—but out of the blue, days before the event, a Lund-synchronised dial clock turned up.

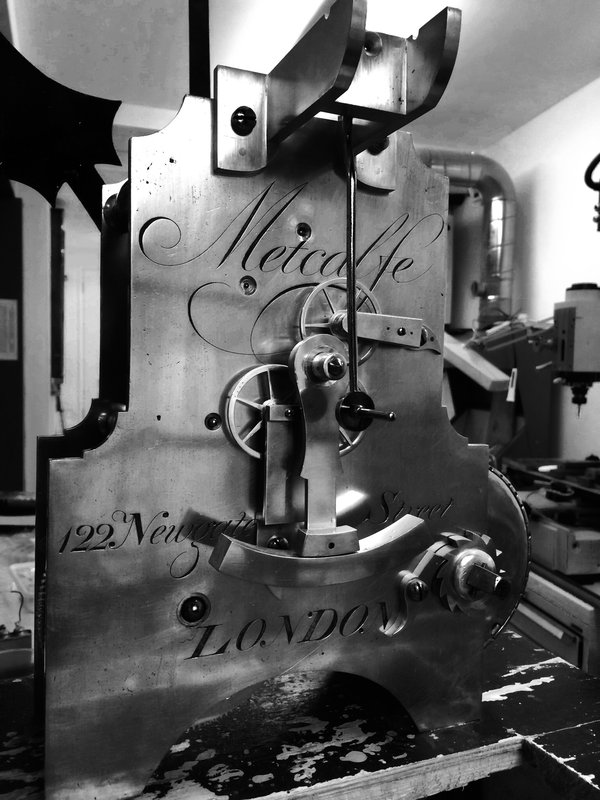

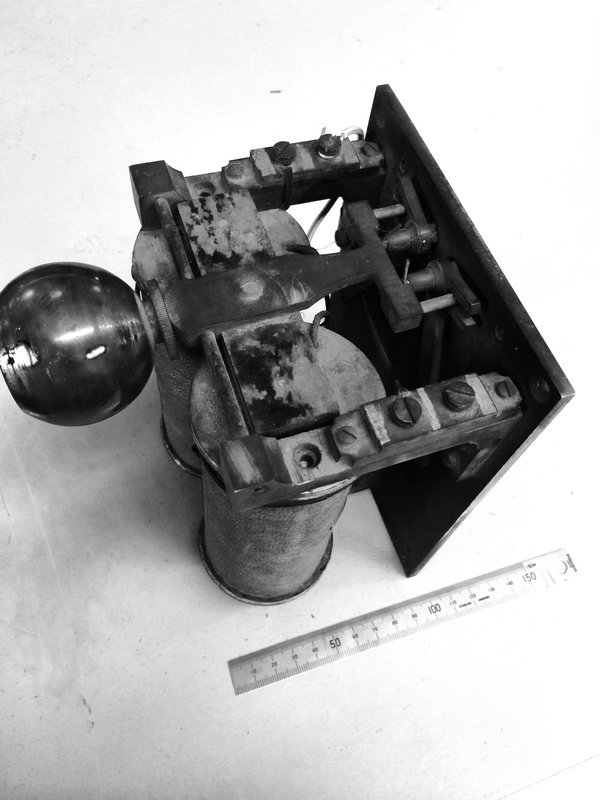

In the following eight years, that was it—nothing else—and then suddenly, through the kind agency of Keith Scobie-Youngs, The Clockworks acquired a wonderful addition a few weeks ago, in the form of an outsized fusée gallery movement, fitted with a massive Lund synchroniser.

The movement is by Thwaites, from the early nineteenth century, and signed elaborately by Metcalfe of 122 Newgate Street, London.

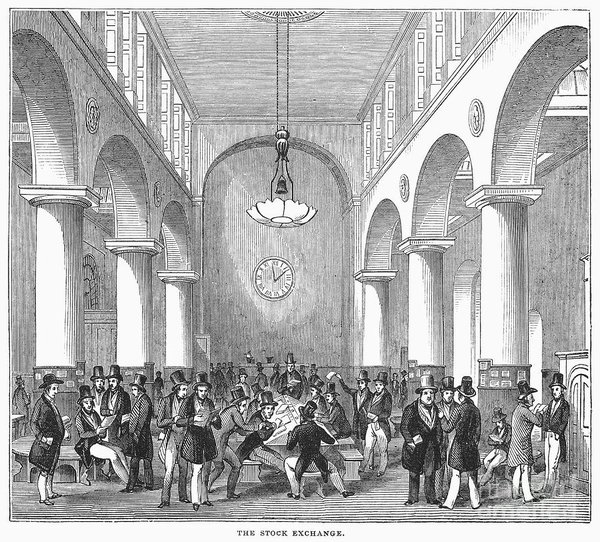

When STC went public in 1886, it listed its clients in the prospectus, and the very institution on which it was being floated appeared second in the list.

The accurate timing of bargains made by the jobbers on the London Stock Exchange was an important matter, and ‘the House’ was an early adopter of the new technology that provided hourly synchronisation of its clocks.

Remarkably, our new addition was one of probably several STC-synchronised clocks that populated ’Change, where it seems to have served for some time.

Each hour, a signal would travel from STC’s offices on Queen Victoria Street around a series of looped networks, energising the coils of the synchronisers. These were the ‘set-top boxes’ of their day, added perhaps many decades after a clock was first made—as was clearly the case with this clock.

The Stock Exchange synchroniser is particularly large, operating two small fingers that project through the dial, to correct the minute hand each hour. The long use of the device is evidenced by the deeply indented witness marks in the tab on the back of the hand, caught by the synchroniser.

.

Overall the movement seems rather outsized for the scale of the dial it ended up supporting—the large counterweight is much more than a match for the 15-inch minute hand.

Sometimes, it’s very hard for us to trace the environs in which our clocks spent their time—and to deduce whose lives they counted out. Thankfully in the case of this remarkable STC clock, there’s an old crank that can tell us a story or two.

Stopping the clock after death

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In a previous post I included an opera scene, in which a woman mentions (sings!) that at times she stops all the clocks in her house. She dreads getting old and wants time to stand still.

One reader told me this reminded him of a poem by W.A. Auden which begins:

'Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

'Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

'Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

'Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.'

But here the motive for stopping the clocks is different. Someone has died, and stopping the clocks in the house of the deceased, silencing them, is an old tradition, similar to closing the blinds or curtains and covering the mirrors. The clock would be set going again after the funeral.

Some people believe stopping the clock was to mark the exact time the loved one had died. The subject was discussed here by members of the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in America.

The French film Jean de Florette, set in the Provence between the wars, contains such a clock-stopping scene. The film is made after a novel by Marcel Pagnol, from which the following quotes are taken.

Jean, an outsider, inherits a house with surrounding land and hopes to make a living there. But two locals, who covet his land, secretly block a source, cutting off his vital water supply.

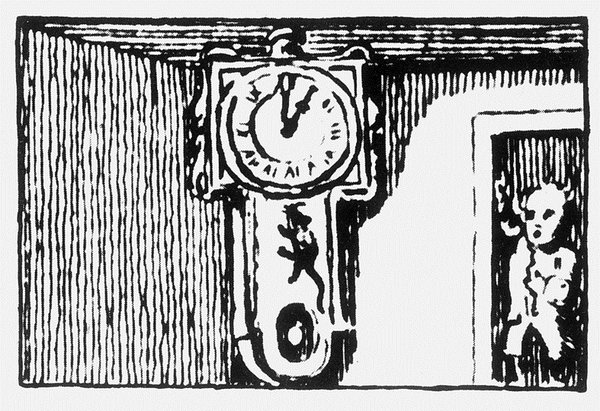

In despair, Jean uses dynamite to create a well, but he dies as a result of the explosion (chapter 37). The doctor, taking his pulse, 'listened for a long time in a profound silence emphasized by the ticking of the grandfather clock', but the man had died.

Then one of the two devious locals, who was in the room, 'crossed himself, walked around the funeral table on tiptoe, and stopped the pendulum of the grandfather clock with the tip of his finger'.

He then tells his comrade in arms 'Papet, I have just stopped the grandfather clock in Monsieur Jean’s house' – a way of saying: he is dead.

The three stills reproduced here are from that scene, which you can see in this short clip.

The clock is a typical Comtoise grandfather clock with a big flower pendulum.

100,000 more free images

This post was written by David Rooney

When I got an email from the Wellcome Trust which began, ‘we have some very important news to announce’, it certainly got my attention.

And they were right: it is very important news indeed, and I’m delighted to share it.

In my last post I talked about the recent release of a million images by the British Library. Already I’ve heard from colleagues and friends who say they have found new evidence amidst its vast collections that is crucial to support their research.

The news from the Wellcome Trust is the same. As of January this year:

'All historical images that are out of copyright and held by Wellcome Images are being made freely available under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This means that they can be used and manipulated freely, for commercial or personal purposes, so long as the original source is acknowledged.'

You can download high-resolution files directly from their website. There are 100,000 images dating from as early as 1000 BCE. You can even get advice directly from Wellcome’s team of researchers, should you be having trouble finding what you need.

Like many in the AHS, I’m interested not only in clocks and watches themselves, but how horological machinery gets embedded in other technologies. So I searched for ‘clockwork’ and, rather than showing you the clockwork trephine (not safe for suppertime), here’s a clockwork picture of an itinerant dentist performing an extraction in the early 19th century. Ouch.

Whether you’re into automata like this, or medical technology, or astrology or philosophy or geology or anything else related to stories of time and its material culture, you’re sure to find something here to delight.

As I said last time, image banks such as this are invaluable treasure troves of historical evidence for researchers, whatever your subject. Serendipitous browsing leads to new leads and new ideas.

Huge thanks to Catherine Draycott and others at the Wellcome Trust (as well as the British Library) for making such a bold and generous decision to open this to everyone.

The Battle of the Three Emperors – or the Battle of the Three Dates

This post was written by David Thompson

I was recently reading Dušan Uhlír’s book The Battle of the Three Emperors and I came across an intriguing fact about the battle of Austerlitz which took place on the 2nd December 1805 between the armies of Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire Empire and Tsar Alexander I of Russia against their invading enemy, Napoleon Bonaparte.

In Uhlír’s fascinating account of one of the most famous battles of the Napoleonic campaign, excepting Waterloo of course, he points out that the battle took place on a different day for each of the three armies.

For Francis II, the date was 2nd December 1805, for Alexander and the Russian army the date was 20th November and for Napoleon, Bonaparte it was 11th Frimaire year XIV.

Francis and his army were using the Gregorian calendar introduced in 1582, although it was not universally adopted throughout Europe – indeed, England didn’t change until 1752. Alexander was still using the old Julian calendar – the Russians did not change to the Gregorian calendar until 1918. Napoleon was using the French Revolutionary Calendar, introduced in 1793, but back-dated to September 1792 to mark the beginning of the new republic and each successive year numbered from then on.

It must have caused some confusion for the Austrians and the Russians when agreeing a date to face up to Napoleon and the French would have had to convert the traditional dates into their new scheme.

…on the other hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have simple, easy to use, single-handed dials. On the other hand, some dials are not so straightforward.

This clock has 'fly-back' or 'retrograde' hands. The hands proceed clockwise as usual but when they reach the end of the scale, each will spring back and then immediately resume its count.

This design allows the dial to have twice the diameter of a circular dial within a given height. This, together with the semi-circular form, makes these clocks suitable for positioning over doorways and they were sometimes integrated within wall panelling.

Fly-back hands are still a popular feature in watches, although these are usually (but not always) the preserve of high-end watches.

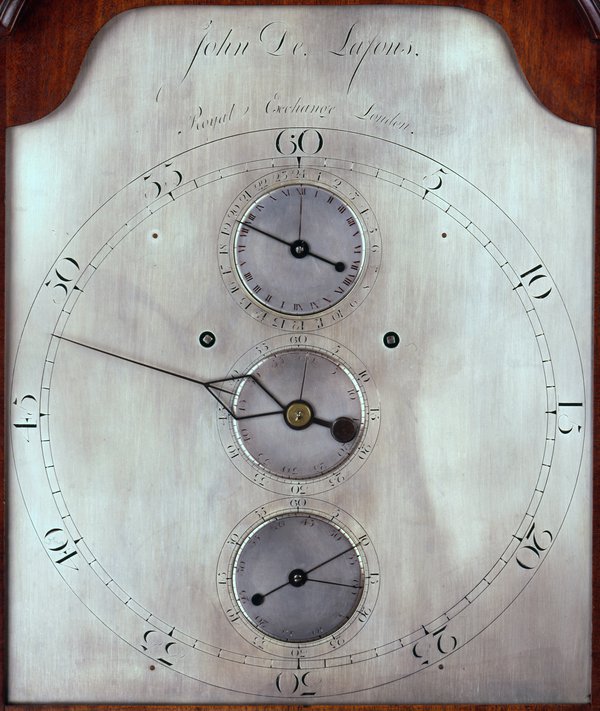

The dial of this regulator (that I have mentioned before for its escapement) has the typical features which facilitate the use of these clocks in observatories and laboratories. All hands are positioned on their own centres for disambiguation. The hours are relegated to a small subsidiary dial and only the minutes have a large hand, for accurate observations.

Less typically, however, this regulator indicates two different systems of time using only one set of hands.

It shows mean sidereal time against the numerals on the main dial plate and mean solar time against the small discs. A mean sidereal day is 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds, i.e. it is about 4 minutes shorter than the 24 hour mean solar day. The discs rotate slightly faster than the hands so that after each day they have accrued the 4 minutes difference. This system is called a differential dial.

Having a clock show both sidereal and solar time might have been a convenience, but a respectable observatory might well be expected to have had separate regulators for providing the required times and so it is possible that this design may have been conceived rather for the use of the (wealthy) amateur.

This watch has not just hands, but arms and fingers too! It is a type of watch known as “bras en-l’air”, which translates as “hands in the air” (and certainly not “bras in the air” – which might apply another aspect of horology altogether). When the pendant is pushed the soldier raises his arms, holding pistols to point at minutes (left) and hours (right).

An experiment in ‘florology’

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

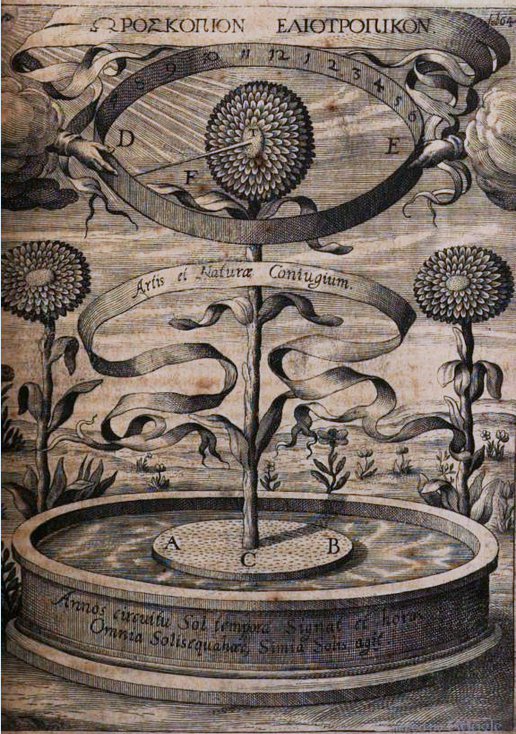

Recently, I have been looking at the role of timekeepers in the history of science and whilst reading around the pre-pendulum era, happened upon a blog-worthy experiment conducted by Athanasius Kircher (1601/2-80).

Kircher, a German Jesuit polymath, applied the then known phenomenon of heliotropism as a method of timekeeping.

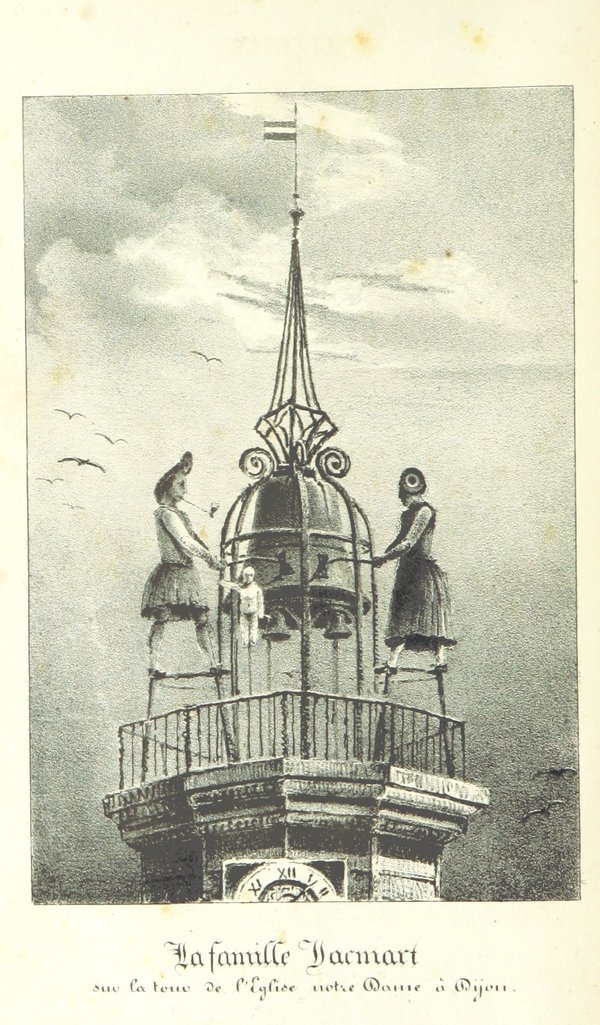

He thought that the daily motion of sunflowers as they followed the Sun was caused by magnetic influence and thus inferred that they could be usefully used as a clock. As can be seen in his magnificent illustration, Kircher planted the sunflower in a cork pot and floated it on water, providing a frictionless pivot, and inserted a pointer through the flower to indicate time against the annular chapter.

Kircher noted that his clock was disturbed by the slightest of breezes and, when kept away from sunlight, it withered and its motion slowed. This, however, did not end the experiment. He tells us that he had the good fortune of meeting an Arab trader who happened to have amongst his aromatic wares a substance with similar horological properties to the sunflower.

The deal was struck and Kircher parted with his sundial signet ring for the horological stuff.

It has to be said that this episode is possibly a theatrical device to colour the account and introduce the use of sunflower seeds and root instead of the plant itself, but worth repeating – even if it’s just an excuse to show a beautiful horizontal sundial ring!

Today, we know that this diurnal motion is caused by sunlight and so Kircher’s clock could never have worked in the way intended, but one cannot help admire his ingenuity in applying a mystery of the physical world to tell the time. M. Becker’s 2011 time lapse movie shows that it is possible to use a flower as a twenty-four hour clock, but only in summertime at a latitude close to the north or south pole.

Graveyards, clocks and bombs

This post was written by James Nye

Things end up in graveyards at the end of their lives, but monuments to the passing of much else can be found in other locations.

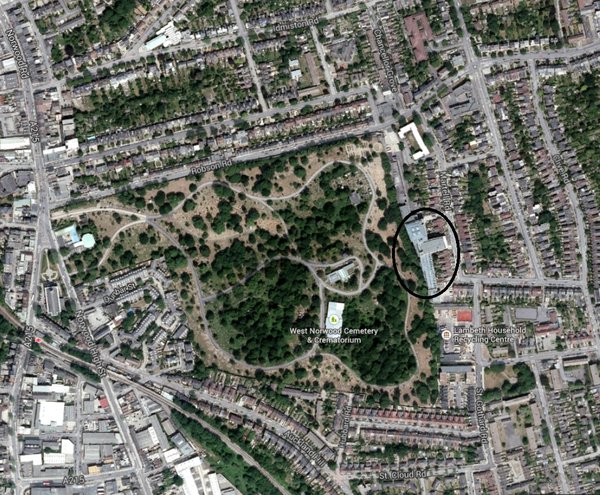

I live in West Norwood, home to one of the ‘magnificent seven’ London cemeteries.

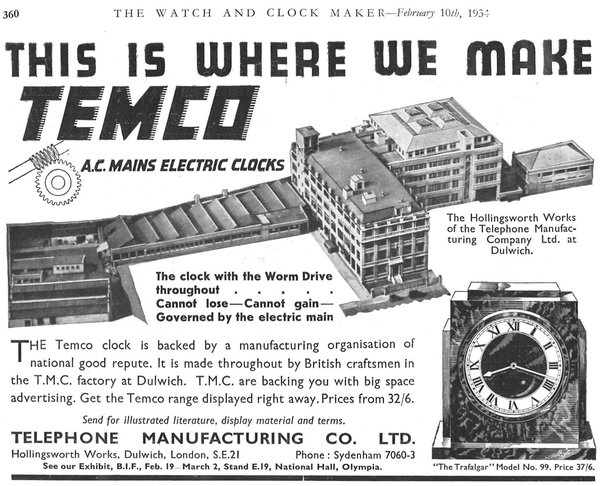

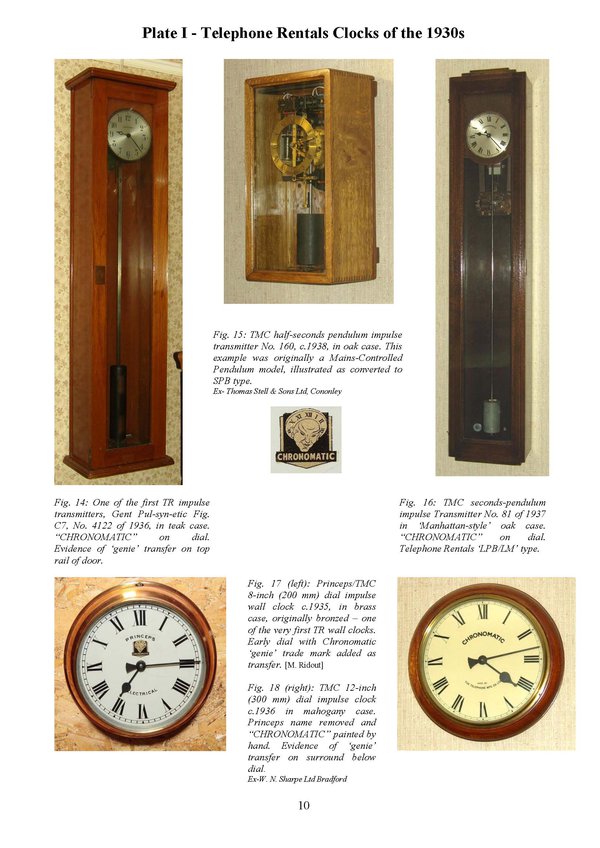

On its eastern boundary lies the Park Hall Business Centre. This thriving modern enterprise occupies the former Hollingsworth Works of the Telephone Manufacturing Company (TMC).

This firm did just what its name suggests, but was also a prolific maker of industrial timekeeping systems, rented out under the name Telephone Rentals. TMC’s ‘TEMCO’ synchronous clocks are featured in the latest NAWCC bulletin.

TMC occupied the Dulwich site from the early 1920s, employing a large local workforce—1,600 by 1937. Workers from the other side of Norwood Road used to talk of ‘walking the wall’ to work, following the long cemetery flank wall, down Robson Road.

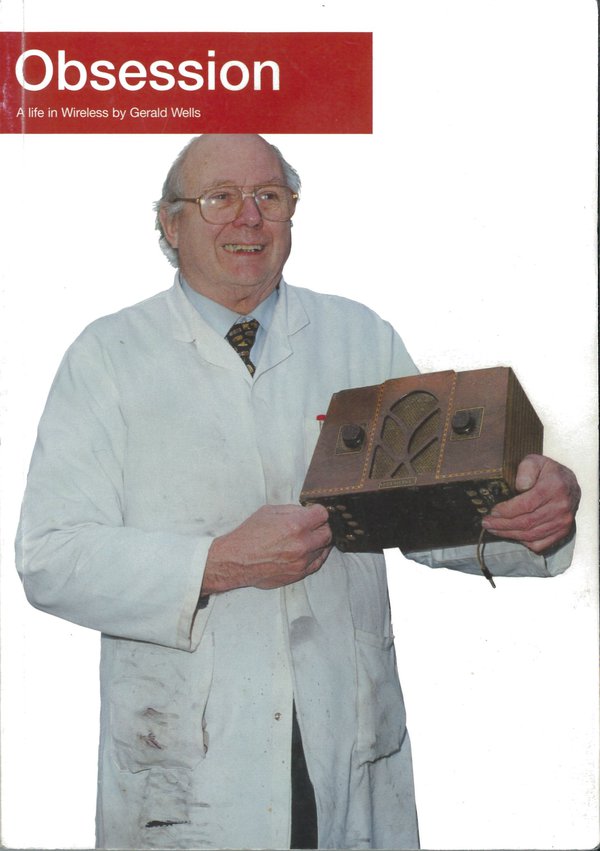

Involved in contemporary ‘hi-tech’, the factory was a natural wartime target—Gerald Wells’ extraordinary autobiography describes twenty-seven bombs falling on the cemetery, targeting TMC, but then the Luftwaffe became:

‘fed up with wasting bombs on Norwood Cemetery so they decided to get the TMC factory by lowering a large naval magnetic mine on a parachute over the building. My sister Margaret watched it come down from an upstairs window […] it knocked seven colours of s*** out of our little Congregational Church’ ( click for a bombsight map —work in progress).

So Hollingsworth Works survived, and TMC/TR had a more successful post-war life than many clock-related concerns.

You can learn much more about the company’s life and products from a superb paper by Derek Bird—these technical papers are a feature of EHG membership. Why not e-mail me to get on board? And put 7 September 2014 in your diaries—part of Lambeth History Month—when The Clockworks will offer a special locally-themed event, featuring TMC.

Musical clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My previous post in this blog was on clocks in opera. How about opera in clocks?

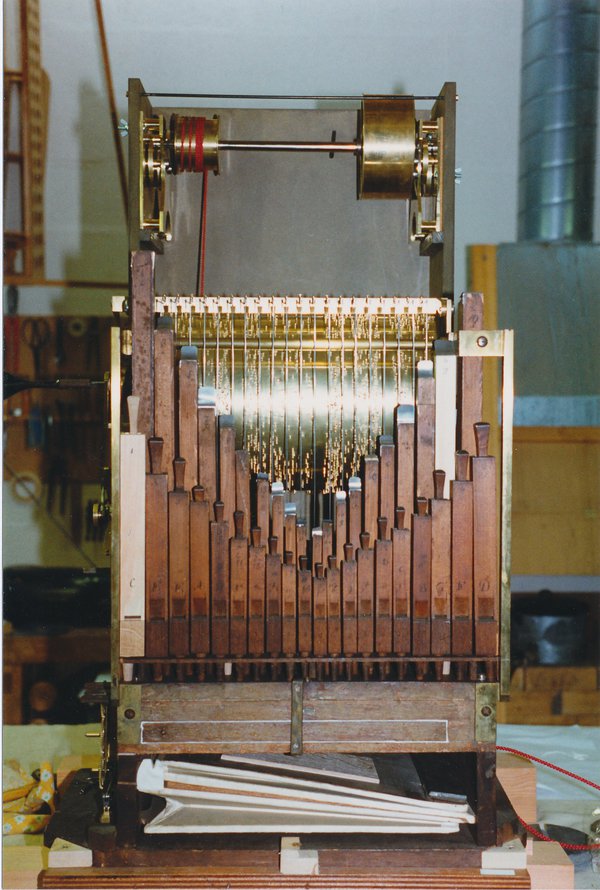

The Handel House Museum is the London home where the composer George Frideric Handel lived from 1723 until his death in 1759. In the 1730s, Handel provided music for a series of musical clocks created by the watch and clockmaker Charles Clay.

These more than man-sized, elaborate pieces of furniture were fitted with chimes and/or pump organs that at the hour and every quarter played musical excerpts from popular operas and sonatas.

Until 23 February the Handel House Museum presents an overview of Clay’s clocks in an exhibition ‘The Triumph of Music over Time’. The centrepiece is a clock on loan from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; other clocks are presented as photos on text panels.

These panels are all on-line here where you can also listen to some of the music that Handel arranged for Clay’s musical clocks, including two pieces from his opera Arianna in Creta. So there you have it: opera in clocks.

Another 18th century maker of beautifully crafted musical clocks was George Pyke. A fine example, dated 1765, is on display at Temple Newsam House in Leeds.

Standing over 6 foot tall on its pedestal, it strikes the hours and has a pipe organ that plays eight tunes. The innards of the Pyke clock are shown below; more photos and details of the clock are here on the website of Brittany Cox, who has made a condition study of the clock and hopes one day to be able to restore it to its former glory.

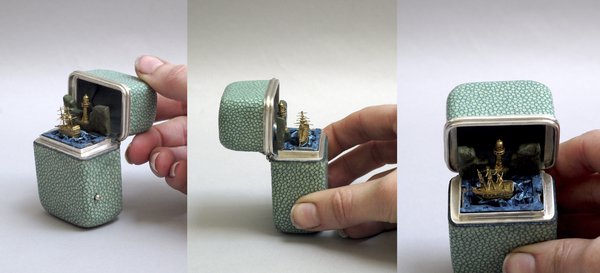

Although a bit off topic – it is not a clock – you may like to know of a musical automaton that Brittany Cox restored to working order during her studies at the Clocks and Related Dynamic Objects Department at West Dean College. A miniature ship, a mere 15mm wide, rocks to and fro, as in a storm, while ‘God Save the King’ plays on a plucked comb; see and hear it here.

For this project Brittany was awarded the annual AHS prize for 2012. For a full description see this article which she wrote for our journal Antiquarian Horology .

With thanks to Ella Roberts, Communications Officer at the Handel House Museum, for her help.

A million free images

This post was written by David Rooney

Just before Christmas, the British Library released over a million historical images from its printed collections onto the image-sharing website Flickr. The images are out of copyright and the library has made them available with a Creative Commons licence which, in short, encourages anybody to use, remix and repurpose them, so long as they respect a few ground rules.

This is a remarkable resource of imagery and will be a boon for anybody carrying out historical research – such as AHS members.

There are countless images of interest in this release, each one of which might augment an existing research project or prompt a new one. The beauty of archives such as this is the opportunity for lateral thinking. You might be researching a particular village, or writer, or building, or period. And you might find an image here that opens up new avenues of research.

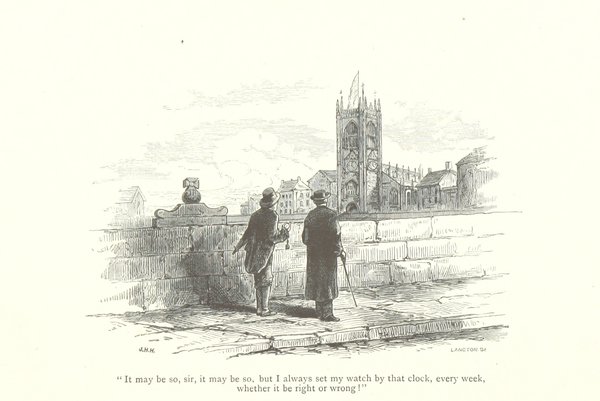

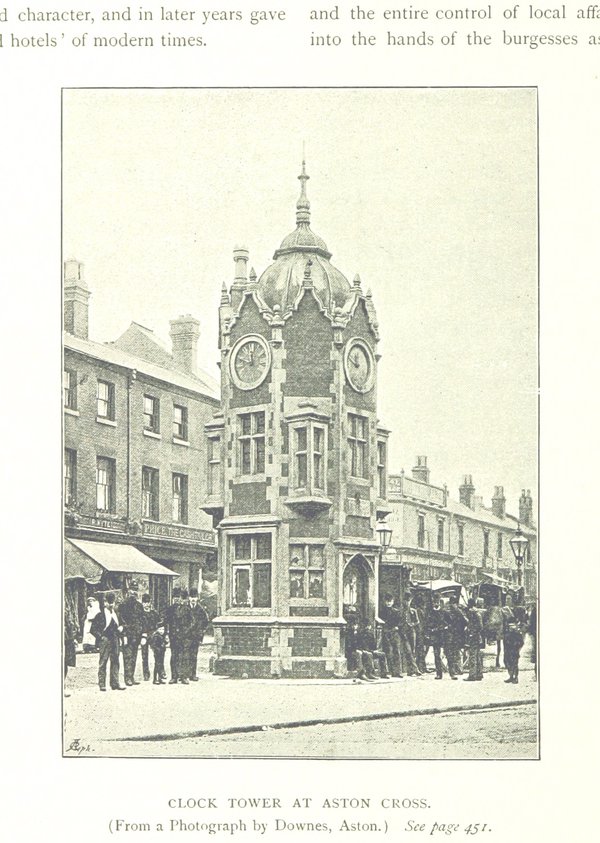

The first four images I found are the result of searching for ‘clock’ or ‘clocktower’ – as you’d expect, lots of public clocks.

But let’s say I’m interested in chronometers. Unfortunately there are no search returns for that word. But then I tried searching for ‘observatory’, and found this image.

It’s from a book on the North Polar Expedition, and it’s a photograph of marine chronometers on show in a US Navy centennial exhibit in 1876.

That led me to this catalogue of the objects exhibited. And on pages 79–81 there’s a remarkable and detailed description of the use of chronometers at the US Naval Observatory in the 1870s. Serendipitous discovery is a wonderful thing.

You’ll probably want to put aside an hour or two browsing these images – and a lot more time following the interesting leads they throw up! Happy hunting, and happy new year.

The sands of time

This post was written by David Thompson

Everyone is familiar with the egg timer, but just how far back in history do these glass timers filled with free-flowing material go?

The earliest known illustration of such a device exists in an Italian fresco dating from between 1337 and 1339 in the Palazzo Publico in Siena. The fresco is called ‘The Allegory of Good Government’ and in it, one of the figures can be seen holding a sand-glass.

Before modern glass making techniques developed, sand-glasses were made using two separate bulbs bound together around a disc with a hole for the ‘sand’ to pass through. Over the centuries all manner of different materials were tried in attempts to achieve a uniform free-flowing performance.

The duration of the timer depended firstly on the amount of ‘sand’ in the glass, and secondly on the size of the opening between the two containers. The two glasses were sealed together with wax and the joint covered and tightly bound. The biggest enemy for these glasses was humidiy – damp ’sand’ was bad for business.

A particularly fine example exists in the British Museum collections, although is has a rather dubious reputation.

It is a composite glass with four separate glasses in a beautiful ebony frame and each glass is designed to run for a different period, one quarter, one half, one three quarters and last a full hour. It even boasts a leather carrying case.

At one time it was said to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots and indeed, at the top and bottom of the frame are reverse-painted glass discs bearing the royal shield of the Tudors and the shield of France with fleur-de-lys. The idea was that this glass was owned by Mary Queen of Scots and Francis II, king of France.

Unfortunately, the Tudor arms are from the wrong period and the lion rampant in the first quarter of the shield is the wrong way round. The leather case is also roughly embellished with the monogram MF for Mary and Francis.

In spite of its later enhancement, this is nevertheless a very fine example of a late 17th century glass.

On the one hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

The last of the five elements is the indicator, the part of the clock or watch that conveys the time.

Early clocks and watches typically only had a single, hour, hand. This was more than adequate for indicating the time as these foliot-controlled timekeepers would typically lose or gain at least quarter of an hour in a day. Minute and seconds hands only became truly useful with the vast improvement in timekeeping that came with introduction of the pendulum in 1657 and the balance spring 1675.

However, the familiarity, simplicity and economy of the single hand meant they never became obsolete. Throughout the 18th century, pendulum-controlled longcase clocks with single hands were very popular in the provinces of England.

There were also some more interesting implementations of the single hand. This balance spring watch has a six-hour dial, instead of the usual twelve-hour dial. With only six hours dividing the circle it offers twice the resolution of a standard twelve-hour dial, thus going some way to making up for the lack of a minute hand.

Next, a single hand with a difference – it is telescopic. The hand extends and retracts to follow the contour of the oval dial, allowing the time to be read clearly. A fixed hand would fall short at the “XII” or “VI” positions, making it harder to read with accuracy.

Another form of single hand can be found on this Japanese pillar clock.

The pendulum controlled movement is at the top of the clock. Below it, the single, hour, hand is directly attached to the driving weight through a slot in the case. As the weight descends over the course of a day, it indicates the time against the linear scale of numeral plaques on the case. The plaques can slide, which allows their positions to be adjusted for the Japanese system of unequal hours.

Single handed watches continue to made by several manufacturers, such as this example owned by myself.

In practice, the time can only easily be read to the nearest five minutes (which is well within the capabilities of its modern movement). However, I find that this is good enough (at the the weekends at least!) and it is a most leisurely way to follow the time.

300 years

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

This year saw the tercentenary of the death Thomas Tompion (b.1639), the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’ and his life is celebrated in two special exhibitions: the first at the British Museum, entitled ‘Perfect Timing’, which focuses on the magnificent Mostyn Tompion and the second, ‘Majestic Time’, at the National Watch and Clock Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Tompion enthusiasts should be further delighted by the announcement of the forthcoming publication of ‘Thomas Tompion, 300 years’. The book promises a wealth of new detail, fresh illustrations and includes Jeremy Evans’s previously unpublished chronology of Tompion’s life.

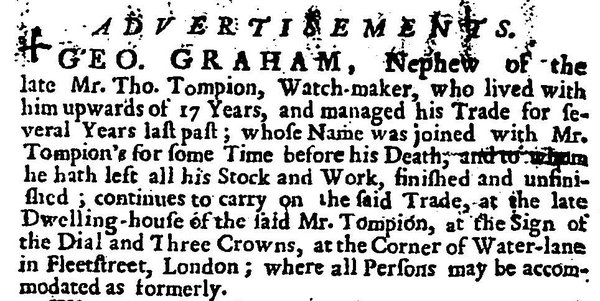

This tercentenary marks not only an end, but a new beginning as Tompion’s nephew by marriage and then business partner, George Graham (c.1673-1751), inherited and continued the business at the corner of Water Lane. As far as I am aware, the earliest announcement of Graham’s succession was first advertised in The Englishman one week after the death .

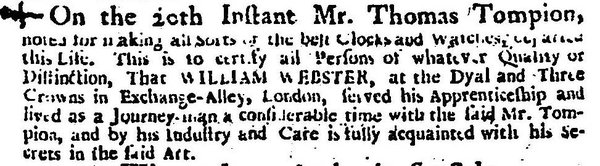

William Webster, however, did not show the same reserve. He had an advert published the day after Tompion’s death in two papers: The Mercator or Commerce Retrieved and The Englishman. His announcement of the death was a thinly veiled attempt to attract business and was repeated in various papers that week.

Unlike Webster, Graham was not apprenticed to Tompion (several publications incorrectly cite Graham as being so). He joined the household sometime around 1676 after gaining his freedom from apprenticeship to Henry Aske.

Evidence suggests that Graham did not serve his entire apprenticeship under Aske and it is currently a mystery as to where he was during the last years of his apprenticeship.

Looking forward to next year there is another important tercentenary, that of the Queen Anne Longitude Act. George Graham played an important role as an encourager and advisor to both Henry Sully and John Harrison in their efforts to produce sea-going clocks and will feature in a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum next year.