The AHS Blog

Watching over us

This post was written by David Thompson

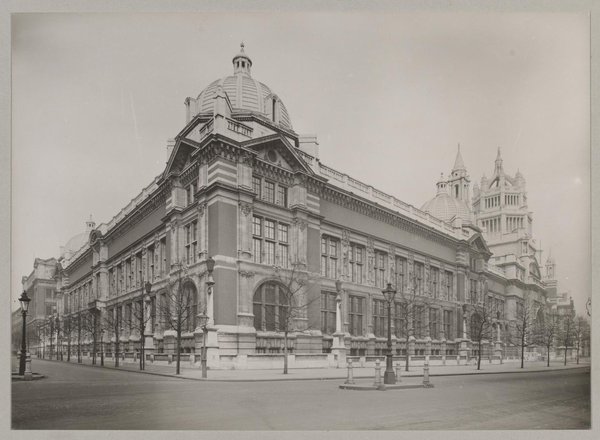

Walking up Exhibition Road in London on the way to the Science Museum, you just have to look to your right and up a bit, and there stands one of our great horological giants.

On the façade of the Victoria & Albert Museum stand a cohort of celebrated figures in Britain’s manufacturing heritage. Thomas Tompion is there amongst some illustrious company.

On his left and right are St. Dunstan, the Patron Saint of craftsmen, sculptor William Torell, printer, William Caxton, goldsmith George Heriot, blacksmith, Huntingdon Shaw, cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale, potter, Josiah Wedgwood, bookbinder, Roger Payne and designer, William Morris.

These figures, finely sculpted in Portland stone, make up part of the museum’s façade designed by Aston Webb and begun in 1899 when Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone.

However, it was not to be until 1909 that King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra officially opened the new building.

The figure of Tompion was sculpted by Abraham Broadbent (1868-1919).

He was born in Shipley, the son of a stonemason. He studied in London at the South London Technical School of Art and went on to become one of the more celebrated sculptors of his time, particularly in works in the baroque style.

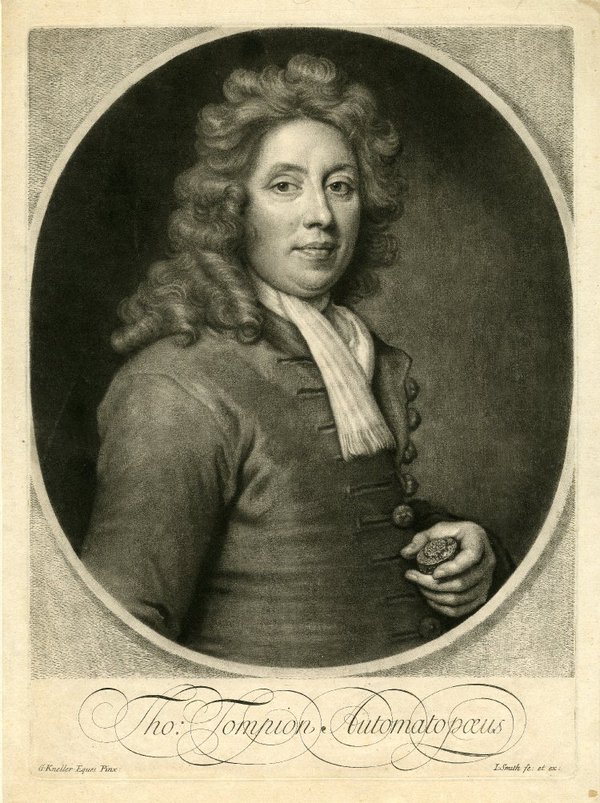

Looking at Broadbent’s image of Tompion, however, it would seem that he had no access to the well-known mezzotint portrait of Tompion by John Smith after a portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Tompion is depicted holding a watch in his left hand, and what appears to be a magnifying glass in his right hand. It would seem that Broadbent did not discuss his proposed figure with a watchmaker, even in the late 19th century, such a visual aid was not the preferred instrument.

Nevertheless, it is great to see that one of the clock and watchmaking giants is there amongst a pantheon of recognized celebrities.

For a detailed account of all the Victoria & Albert Museum sculptures around the building façade, see http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/misc/va/facade.html

Sushi, saké and a send-off

This post was written by James Nye

December 2014’s Antiquarian Horology featured a clock made in 1573 by De Troestenbergh in Brussels, rebadged and given as a gift (by Spanish survivors of a 1609 shipwreck off Japan) to the great Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

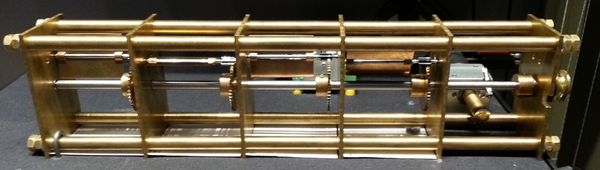

In May 2014, Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks worked on conserving the clock in a Japanese shrine, its home since the early 17th century, measuring and photographing everything.

The authorities wanted more than just conservation – they wanted a replica of the movement, sitting alongside, so that visitors could understand the magic of this striking and alarm clock, four centuries old and plaything of their most revered Shogun.

In August 2015, Johan and David Thompson (the project’s ambassadorial godfather) travelled to Japan to witness the significant honour accorded to the replica on its arrival and installation.

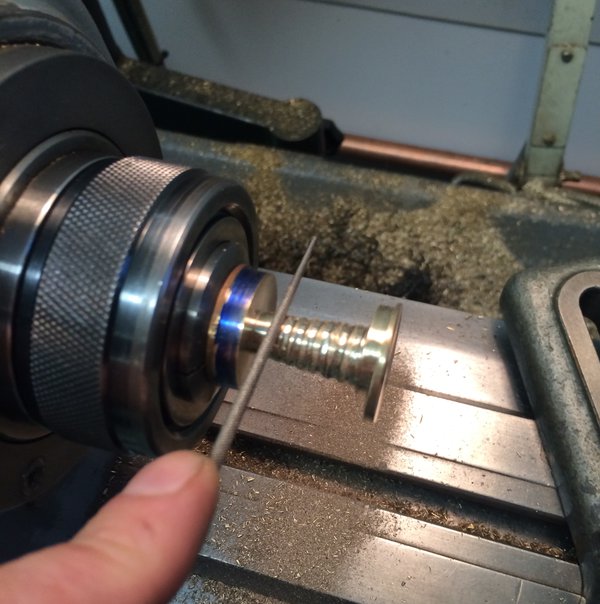

This was no ordinary project. Johan could only rely on details taken over a week.

From mid-2014 to mid-2015, he devoted hours ultimately uncountable to producing a working copy of the movement. Pillars were turned with a hand graver, fusees roughly filed out by hand, flies cut and filed from the solid, shaped plates pierced out of steel plate, and so on.

Wheel teeth were formed using modern cutters, and modern machinery played a large role, but it was a year spent file-in-hand, forming, shaping and finishing.

Others contributed – notably the Whitechapel Bell Foundry for the bell, while the solid silver dial and hour hand were decorated by members of the Hand Engravers Association.

The original sits in a shrine, while Johan entered near monastic isolation for a year.

In August 2015, to mark his own long journey, to thank the many who had helped, and also to enlighten friends who had not seen him for months, The Clockworks hosted an evening of sushi, saké and Asahi. This was a chance to see the working replica before its long journey to Shizuoka, joining De Troestenbergh’s original.

It was a great evening, celebrating the traditional internationalism of horology in which a Dutchman in London worked to an ancient Flemish design to produce a clock for a Japanese shrine.

Campai!

BHI Clock & Watch Conservation and Restoration Forum, 5th September 2015

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Earlier this month the British Horological Institute hosted a day of lectures and discussion relating to horological conservation and restoration at their headquarters in Upton Hall.

![Upton Hall, headquarters of the BHI (Image: Andy Stephenson [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/Upton_Hall_-_geograph.org_.uk_-_4563-1.width-600.jpg)

The terms 'conservation' and 'restoration' are applied to different philosophies of approach to maintaining and repairing objects.

Conservation typically describes an approach of minimal intervention, i.e. attempts to preserve the existing material of a clock or watch as far as possible, whilst still enabling it to serve its required use.

Restoration can describe attempts to revert a clock or watch (that has received alterations over the years) back to its conjectured original state. This typically involves involves the alteration or removal of existing material which, even if not original to the object, can be considered to be part of its history.

There are proponents and opponents of each approach, with many falling somewhere in-between.

There is no black or right – every conservation project is different. The differing motives of the stakeholders (who might include horologists and their clients, or visitors to a museum) and the intended use of an object are all valid considerations in the decision-making process which affects the outcome of a project.

The forum aimed to explore these issues through a series of talks from professionals in the field.

The AHS was very well represented with six of the seven speakers being members:

Ken Cobb – Welcome and Introduction

Alison Richmond – ICON’s Perspectives

Matthew Read – Conservation Training and Education in Horology

Oliver Cooke – Managing Dynamic Objects in Museum Collections

Chris McKay – Conservation on Larger Objects (Turret Clocks)

Keith Scobie-Youngs – Working with Others – Project Management within Conservation

Jonathan Betts – Conservation/Restoration for the National Trust and Other Heritage Organisations

The forum ended with a positive and interesting open panel discussion.

One of the key messages of the day was that the BHI and all horological practitioners have a key role in helping to educate, as widely as possible, all stakeholders in the conservation process on these issues because only with this knowledge might they know how their decisions in the present will affect our heritage in the future.

The forum was thus a very positive contribution towards this vital aspect of antiquarian horology and Kenneth Cobb and the BHI must be lauded for making it happen.

Taking the first watch

This post was written by Mat Craddock

It’s possible that we may never know for sure when the first wristwatch was made, although that hasn’t stopped a number of Swiss brands laying claim to the production of some iteration of that ur-device.

The Patek Philippe N° 27’368 is such a piece – a six line, gilt, cylinder escapement encased in a rectangular gold bracelet with a hinged, hunter-style cover – although it’s not clear who originally commissioned it from Antoine Norbert de Patek and Jean Adrien Philippe.

The watch is usually behind the well-maintained glass of the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, so it was wonderful to be able to see it as part of the Watch Art Grand Exhibition in London’s Saatchi Gallery during May.

This exhibition took the visitor through an immersive area showing an introductory film, introduced them to metier d’arts and other decorative skills, and included over 400 pieces, from automata to automatics, which spanned almost five hundred years of watchmaking.

At the end of the route, British watchmakers answered visitors’ questions about case refinishing, movement assembly and the chiming mechanism of a minute repeater movement.

Patek N° 27’368 was made primarily as a timepiece to be worn on the wrist, rather than as a piece of jewellery (i.e. the bracelet is of secondary importance). That must have required, one imagines, a great leap of faith on the part of Messrs Patek and Philippe.

While wristwatches gained popularity with women during the 1880s and 90s, and were also produced for men as military timekeepers during a similar period, the earlier oblong-shaped repeater for wristlet sold to the Queen of Naples on 5th December 1811 by Breguet, appeared to have made no horological or sociological impact at all.

N° 27’368 was finally sold to the Countess on November 13, 1876, some eight years after it had first been built.

Chronometers in hell

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In my previous post, ‘Having a smashing time’, we saw how watches are being tested for shock resistance, which can involve some pretty heavy handling.

Another method of testing timepieces is prolonged exposure to heat and cold. This was especially important for marine chronometers, who would travel to all parts of the globe, so it was important to determine to what degree their rate was affected by temperature fluctuations.

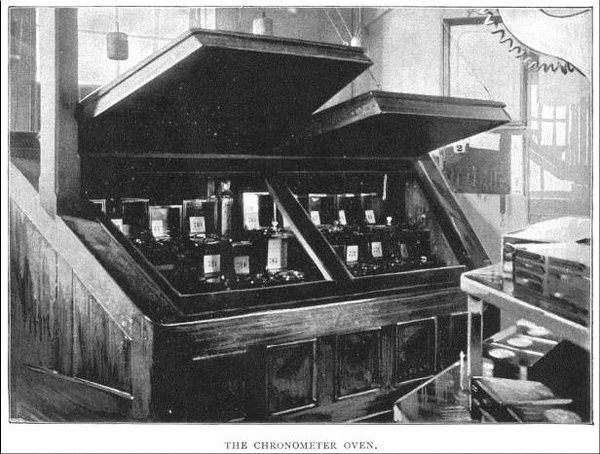

The Time Department at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where the rate of chronometers was tested, had a large oven in which chronometers were kept for eight weeks at a temperature of about 85 or 90 degrees Fahrenheit, that is around 30 degrees Celsius.

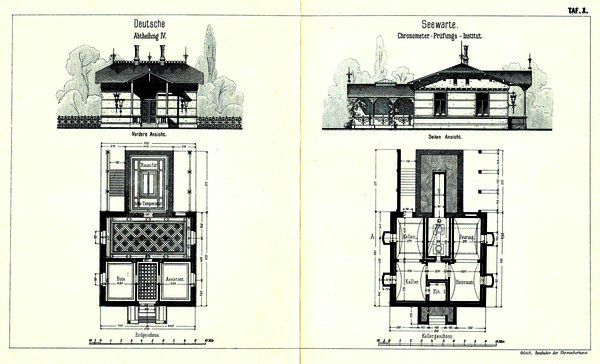

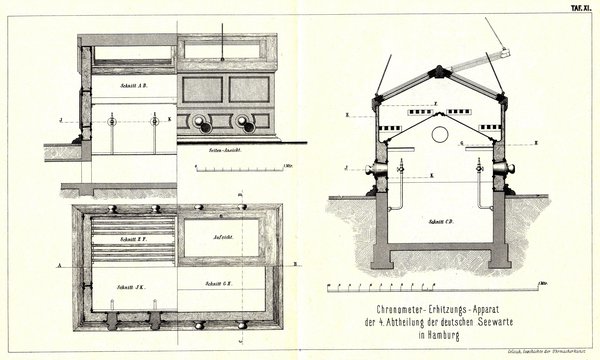

A recent article in Antiquarian Horology had a section on chronometer testing facilities in 19th-century Germany.

In Hamburg they had both an ice cellar and a gas-heated oven. The naval observatory in Wilhelmshaven was less well equipped:

'Neither an ice cellar nor a heating apparatus was available. The radiators of the central heating acted as makeshift for the latter, and tests in lower temperatures were conducted in winter by opening the windows. Sometimes the required temperature of 5º could not be reached due to mild weather'.

Manufacturers of chronometers could have their own heat and cold testing apparatus.

An oven and an ice-box used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons are in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. Normally these two objects are kept in storage, but some years ago they were taken out for display in a temporary exhibition ‘Time Machines’.

When I visited the exhibition, the curator, Dr Stephen Johnston, told me that at first sight some visitors thought the ice box was a toilet!

Sir George Airy, the late Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, in one of his popular lectures drew a humorous comparison between the unhappy chronometers, thus doomed to trial, now in heat and now in frost, and the lost spirits whom Dante describes as alternately plunged in flame and ice.

He was referring to Dante’s La Divina Comedia, Book One: Hell, III, 76-82:

'There, steering toward us in an ancient ferry came an old man with a white bush of hair, bellowing: “Woe to you depraved souls! Bury here and forever all hope of Paradise: I come to lead you to the other shore, into eternal dark, into fire and ice.”'

Commemorating an invasion that never happened

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

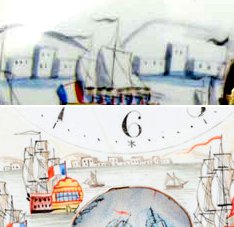

Last month saw the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic era. To mark the anniversary, this week’s blog posting looks at two curious watch dials. The unusual point being that they both appear to come from the same manufacturer, but were made to celebrate victories on both sides of the conflict. One of which never happened.

The first of the two watch dials was made around 1798 when the prospect of a French invasion of England was real and, for many, a terrifying prospect.

Rumours abounded of the French rafts that would carry tens of thousands of troops and weapons to English shores. The images of these vessels distributed by the printmakers ranged from the allegedly factual to the overtly ridiculous.

The French perspective was bullish about the prospect of invasion. Not only were they confident of success, but they also believed that the English would, for the most part, welcome the invasion.

Gillray’s print (above) records that there were indeed those who may have welcomed the French. Whig collaborators are shown on the right-hand-side of the picture trying to winch the French transporter ashore and their efforts are being foiled by Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, seen as the wind blowing the flotilla to destruction.

The dial depicts the ‘descente en Angleterre’ with a more traditional fleet of ships sailing towards the heavily defended English shoreline and serves as a useful glimpse into the mind of the manufacturer, keen to capitalize on the bullish French mood of early 1798.

The scene on the second dial is identifiable as the Battle of the Nile because of the burning ship on the left-hand-side of the image. This represents the French Flagship, L’Orient, which exploded with such violence that fighting was temporarily halted and it became a symbolic feature in popular representations of the Battle.

There is a near-identical row of box-shaped buildings placed along the horizon on both dials. This suggests that they both came from the same source. Such buildings seem more appropriate for the northern coast of Africa than the southern shores of Britain and so it was probably a generic depiction preferred by the artist.

As an asides, the invasion watch dial has a later counterpart in the Museum’s medal collection. A rare sample medal was struck in 1804 with dies intended to be used in London by the victorious French conquerors. Despite amassing a substantial force in the Boulogne area, the embarkation was prevented, principally by the diversion of troops and resources to the Battle of Ulm and, secondarily, by the English blockades.

Inspired reforms – magnificent outcomes

This post was written by James Nye

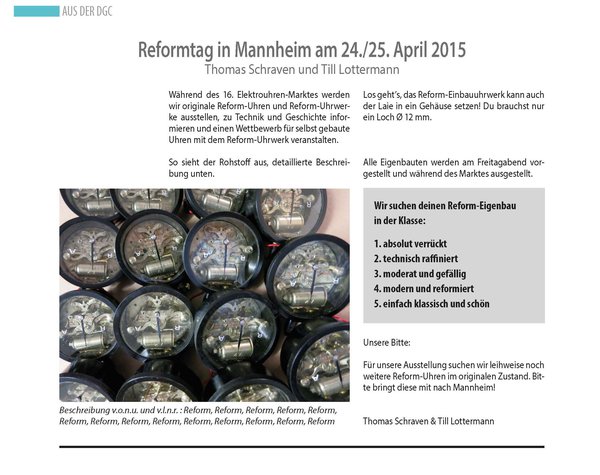

In May 2014, I blogged about a competition to devise uses for new-old stock 1950s Calibre 5000 Reform movements that had turned up at the annual Mannheim electro-fair.

I judged the entries on 24 May this year, and what an amazing event to witness. Here was a beautifully executed movement, simple, reliable, long-lived, but criminal to hide.

How to incorporate it in a modern design, and achieve a functional clock, when the attractive side of the movement would necessarily normally face the rear? In significant style, it turns out……

Ivo Creutzfeldt ignored convention and went for pure schlock with his tongue-in-cheek ‘winged chariot entry’.

Thomas Schraven offered a couple of entries, one channelling a strong modernist theme – using two movements, one for display, the other for timekeeping.

Eddy Odell showed considerable lateral thought, introducing the movement into a glass mug, keeping the movement visible to the top, while driving digital minute and hour bands in the base, the battery neatly hidden.

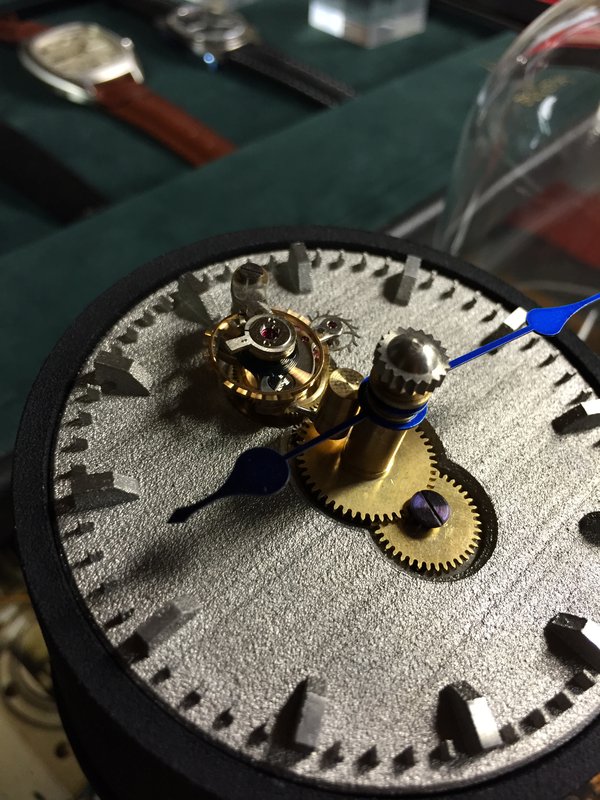

Till Lotterman and his home team colleagues offered a remarkable test exercise. Using original parts, they recut elements to form a tourbillon, brought out on the dial side of the movement, achieving real spectacle ( film here).

Not only this, they 3D printed a stylish stainless steel dial, and also 3D printed an open-sided plastic tubular case, with internal mirror to reflect the movement. Later we were treated to a lecture on the extraordinary possibilities emerging for 3D printing.

Finally, the most talked about item in the competition, Frank Dunkel’s inspired diorama clock, using the Reform at the centre of a roundabout, driving hidden arms carrying neodymium magnets, in turn propelling a VW Beetle (minutes) and VW van (hours) against perimeter hour markers ( film here ).

Power even arrives by wire supported on telegraph poles. Absolutely inspired!

The whole party retired to a restaurant for the evening, at which, amidst characteristically heroic levels of consumption, we celebrated the amazing results of our competition – prizes all round.

AHS Wristwatch Group

This post was written by Laura Turner and Rebecca Struthers

The Antiquarian Horological Society is pleased to announce the formation of a new specialist group focusing on the emergence and development of the wristwatch.

There has been an increased interest in vintage and antique wristwatches in recent years, but a perceived lack of corresponding published scholarly research. The Wristwatch group plans to promote and encourage the study of the history and development of wristwatches, through meetings, education and publications, including articles in the Journal or technical papers for Group members.

Members of the Wristwatch Group will have regular meetings, in the form of lectures, short talks, bring and discuss sessions, and visits to exhibitions, private collections and centres for the practice and study of watchmaking both in the UK and abroad.

The Group will bring together enthusiasts keen to learn more about the origins, makers, techniques, family and corporate histories and indeed any of the material and cultural aspects associated with wristwatches.

All are welcome, whether new to the subject or recognized authorities.

The group will be chaired by Rebecca Struthers, watchmaker and doctoral researcher of antiquarian horology at Birmingham City University, along with Laura Turner (secretary), one of the curators of the Horological Collection at the British Museum, supported by Mat Craddock, and Tracey Llewellyn, editor-in-chief of specialist wristwatch publication Revolution magazine.

Announcements of forthcoming Group meetings (and subsequent meeting reports) will be included in Antiquarian Horology, and will be listed at www.ahsoc.org and via our subscription mailing list.

Membership of the Group is open to any member of The Antiquarian Horological Society.

To join the Wristwatch Group, or to find out more, please email wwg@ahsoc.org.

Plastics in horology- AHS funded PCIP course

This post was written by Tabea Rude

In order to gain a wider understanding of the conservation of plastics, its history and its newest applications, the AHS recently paid for me to attend the Conservation of Plastics short course taught by Yvonne Shashoua at West Dean College.

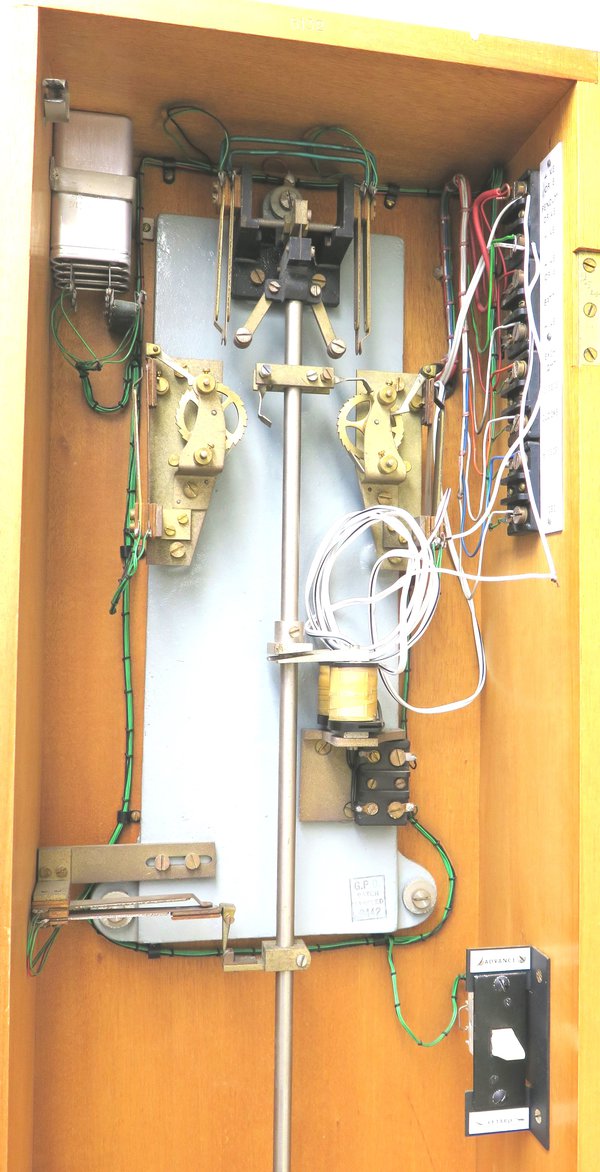

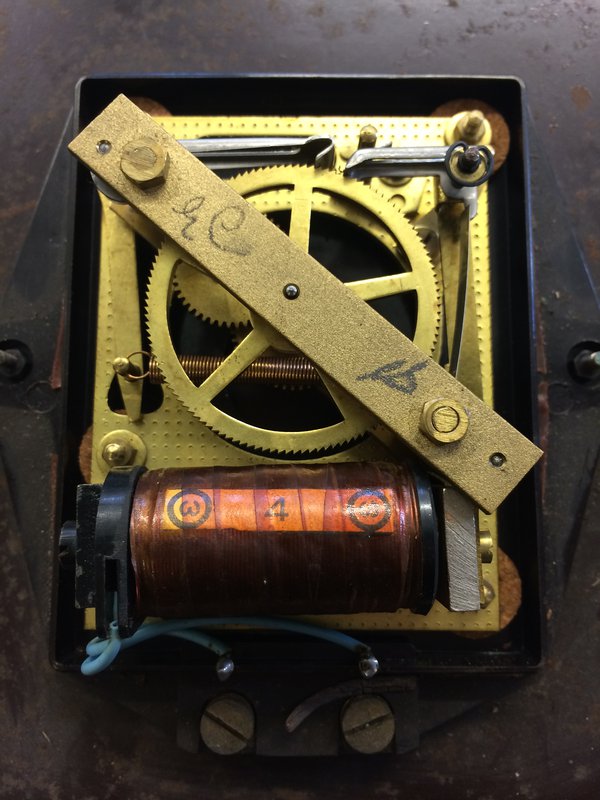

This course proved to be advantageous for an investigation of the degradation of insulation materials in Post Office Type 36 time transmitters as part of the MA Conservation Studies programme at West Dean College.

During the course it became evident how interlinked plastics are with our life.

Starting off as a random material with varying compositions, cooked up in private households it developed to a diverse material invading every corner of our universe.

As a material between waste and high precision engineering, plastics are subject to multiple dilemmas, one of them being its conservation for future generations.

As part of the course, identification techniques were discussed and carried out. By exploring the properties of different plastic families, it became clear that a mixed media object such as the Post Office Type 36 time transmitter, containing at least five different types of plastics, metals and wood, would challenge preventive conservation techniques.

Some plastics such as PVC, often used for wiring in the PO Type 36, should be kept enclosed to avoid the loss of plasticiser. However, other plastics, that tend to off-gas, should be subject to an absorbent such as Zeolite, Silica gel or activated carbon.

On that account preventive conservation of mixed media objects such as the PO Type 36 is at best a compromise.

As a result, this course was an eye-opener to a material we take for granted today. Experiments conducted within the framework of the PO Type 36 study were significantly influenced and informed by the course and discussions had with conservators working in the field of plastics.

Permission to come aboard

This post was written by David Thompson

All made in the 1580s, there are three surviving clock-automata in the form of medieval ships, made by Hans Schlottheim in Nuremberg.

One, a silver nef made for the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

A second, larger and more elaborate example in gilded copper exists in the Musée de La Renaissance in the Chateau d’Écouen near Paris.

The third example similar in many ways to the Écouen nef, resides in the British Museum.

These automata ships were made as table decorations designed to trundle along the banquet table playing music and firing their cannons at the end of their performances. What a way to impress your dinner guests in the 1580s.

Looking at the British Museum nef, it is clear that, with the exception of just one figure standing on the upper rear deck, all the figures on the ship are more recent cast copies of this one original.

One of the problems with automata such as this is what happened when they went out of fashion. Clearly such a thing could not be shown as an impressive demonstration of wealth at banquets time after time.

It is known that the Augustus, Elector of Saxony (1526-1586) had one of these table entertainments – there is a detailed description of just such a machine in the inventories of the Elector’s Kunstkammer from the 1580s. But what happened later?

You can just hear one of the guests at a second outing of the nef saying 'come on Augustus, we’ve all seen that, don’t you have anything new for us?'

When the nef, became less of a wonder and more of a curiosity, you can imagine a small child insisting that the figures be removed so that they could be played with individually. After all, the machine itself had ceased to function properly years ago.

This is speculation of course, but it might well explain the absence of figures on the ship when it appeared in England in 1866 and was bought by Octavius Morgan MP who then gave it to the British Museum.

Intriguingly, in 1983 a figure came up at auction in London and investigation suggested that there was every possibility that the figure was an original from the nef in the British Museum.

It was purchased by Rainer Zeitz Limited, but when they heard about the possibility that it came originally from the British Museum nef, they very kindly donated it to the collections.

For more information on these wonderful machines, see:-

http://musee-renaissance.fr/objet/nef-automate-dite-de-charles-quint

http://www.khm.at/en/visit/collections/kunstkammer-wien/

Julia Fritch (ed), Ships of Curiosity , Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2001.

The AHS 2015 Annual Meeting

This post was written by David Rooney

We welcomed over 100 members and guests to a packed full house at the National Maritime Museum for our 2015 Annual Meeting last Saturday. The sun shone, the atmosphere was buzzing, and we were given a superb day of talks and conversation.

The theme this year was ‘time and transport’ and, outside the museum, AHS members had brought a stunning selection of vintage cars to help set the scene.

During the morning session, we had fascinating talks by Peter Burt on RGS explorers’ watches; Tabea Rude and Erika Jones on zig-zag control; and Rory McEvoy on a Perregaux advertising campaign (apologies for the poor quality indoor photographs!)

After lunch and the society’s AGM, we heard from our new President, Lisa Jardine, on sea-going clocks; Jonathan Betts on polar expedition chronometers; and James Nye on the history of car clocks.

We were delighted to learn that Professor Jardine has recently been made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society.

We also marked the handover of the chairing of the society from David Thompson to James Nye by seeing David awarded a Fellowship of the AHS. Our huge congratulations and thanks to Lisa, David and James.

It was great to see so many members and guests from all around the country, of all ages and with all sorts of interests—represented also in the wonderful variety of speakers and lectures.

Thanks to you all for coming—and we look forward to the coming year with great excitement!

Can bonded solid lubricants preserve the teeth of running clocks?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Antiquarian clocks are still in widespread use. However, like any machine, mechanical clocks wear out as they run and, to keep them running, repairs will inevitably be necessary.

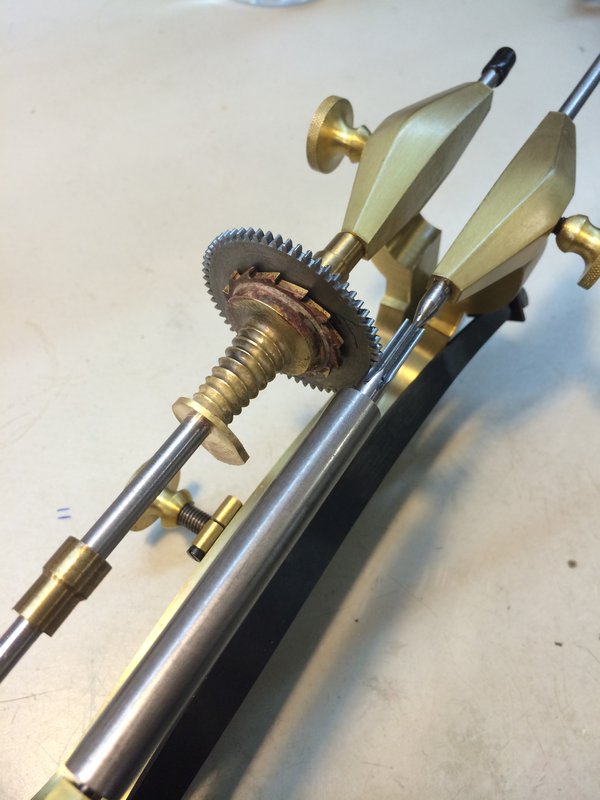

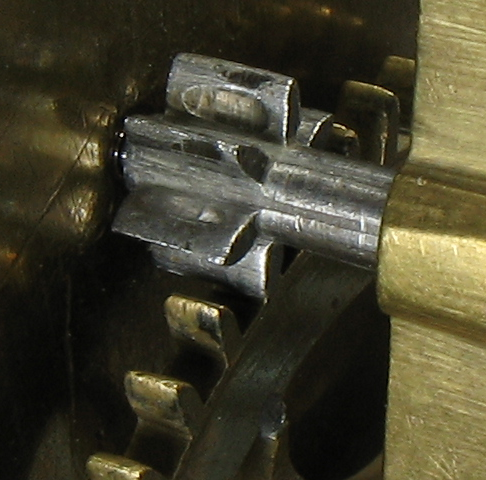

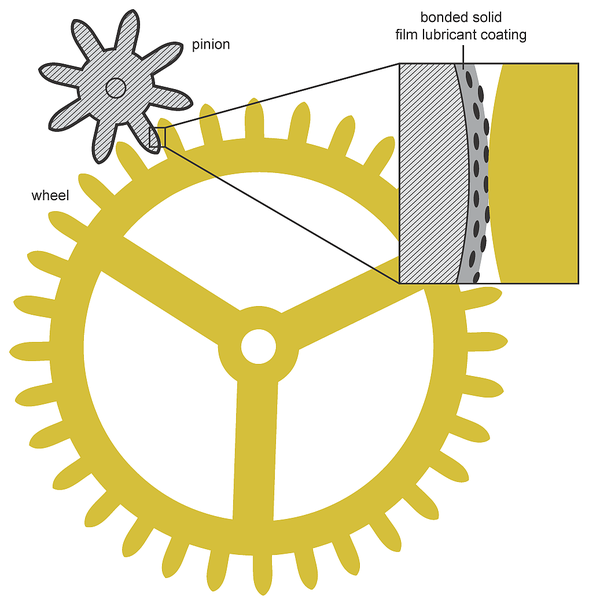

The image above shows a three century old longcase clock pinion that is well worn. Such a change in form will hinder the correct running of the clock until, eventually, it may no longer run at all.

Current repair techniques involve replacing the lost material or the whole gear. Either method is likely to result in loss of evidence of the clockmaker’s original work. This information is important as it can help us to assess the authenticity and origins of clocks.

It would therefore be useful to find a way to reduce the wearing of the teeth in the first place.

Liquid lubricants, e.g. oils, are generally not used on the teeth of clock gears as they are typically exposed to the air, from which dust can mix with the oil to form an abrasive, or chemicals can form which can corrode gears.

Bonded solid lubricants (B.S.L.s) are dry and do not absorb contaminants from the air. B.S.L.s contain particles of dry lubricant, such as graphite, suspended in a binding agent, such as epoxy resin.

They are applied as a liquid which cures to form a hard, dry coating. This coating can both lubricate and act as a sacrificial wearing layer. B.S.L.s might therefore be a useful treatment for preserving the gears of clocks.

Over the last year at the British Museum, where we run antiquarian clocks in the gallery, I have been conducting trials of B.S.L.s on model gear teeth as part of an MA Programme in Conservation Studies at West Dean College.

The B.S.L. that was tested was found to reduce wear compared to uncoated gear teeth. However, scientific analysis showed that it contained chemicals that are unsuitable for use on historic parts.

There are however many other types of B.S.L. and, given the promising results, I plan to test more. It is hoped that this will eventually lead to a treatment to help to keep the antiquarian clocks running with their original gears.

Look out for more information in future editions of our journal, Antiquarian Horology.

Having a smashing time

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

On my twelfth birthday I was given my first watch.

I remember that it had the word ‘shockproof’ stamped on the back and that I wondered just how ‘shockproof’ it was. Mercifully I did not try to determine the limits of what it could take.

On Wikipedia I find that ‘shockproof’ should be understood as ‘shock resistant’, and that there is an international standard which specifies the minimum requirements and describes the corresponding method of test.

It is based on the simulation of the shock received by a watch on falling accidentally from a height of 1m on to a horizontal hardwood surface.

In the test the shock is usually delivered by a hard plastic hammer mounted as a pendulum. Some manufacturers are more ambitious.

Under the heading ‘Having a smashing time: Making sure your watch stands the test of time’ a newspaper article describes and illustrates the many types of torture to which the Swiss factory of IWC (International Watch Company) subjects its timepieces.

The impact test is illustrated here with images from the article. A metal pivot, weighted with a 10kg block, is pulled upright, then swings round to hit a watch held in a vice. A cotton sheet is laid out to catch the watch, and technicians check after each impact to see that it’s still ticking perfectly.

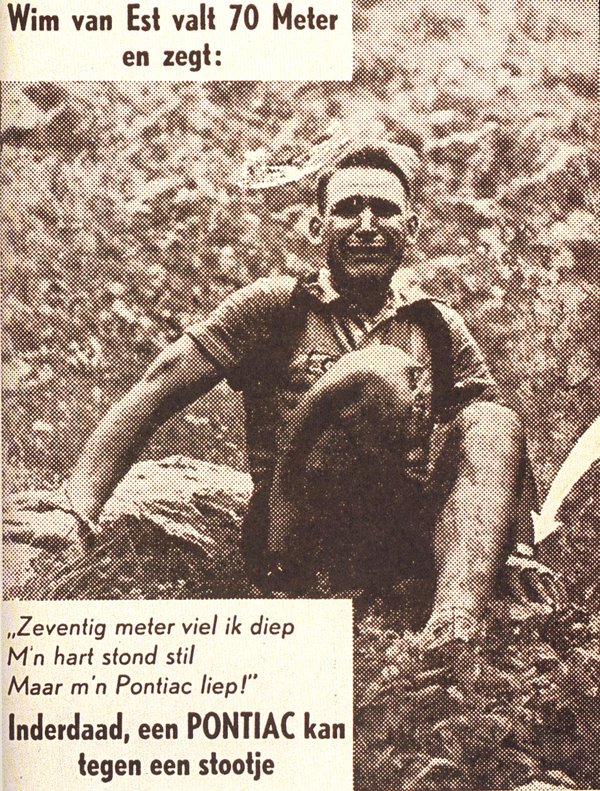

A less carefully planned demonstration of the shock resistance of a watch was given during the 1951 Tour de France, the annual cycle race.

The watch manufacturer Pontiac had sponsored the Dutch team by supplying them with wristwatches. One runner fell and dropped seventy meters down the side of the mountain.

Amazingly, he was not seriously injured. Even better for the sponsor, his watch was still ticking. Pontiac made a successful publicity campaign out of it.

Harrison decoded: towards a perfect pendulum clock

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In July 2014 the NMM hosted on one-day conference, entitled Decoding Harrison, which presented the story of around forty years of collaborative research into John Harrison’s complex and surprising pendulum clock theory.

During the conference the exciting result of a previously unannounced and unofficial test of Martin Burgess’s ‘Clock B’ at the Royal Observatory was revealed.

‘Clock B’ is one of two clocks made from modern materials, chiefly duraluminium and invar, that follow the perceived format laid out in Harrison’s convoluted text: Concerning such mechanism… the lengthy title gives the reader an accurate sense of the complexity of the book itself.

For example, footnotes occasionally run across more than one page and if that was not enough, some even have their own footnotes. In short, it is not an easy read.

The unofficial test was conducted with the clock sealed into a Perspex case, which was made tamper-proof by applying two wax impressions, kindly provided by the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers and the National Physical Laboratory on 1 April, 2014, over wires threaded through the nuts and bolts that hold it shut.

On 6 January, 2015 – some 280 days after the case was sealed – Museum staff and the Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, Jonathan Betts, gathered to witness the going of the clock and initiate an official 100-day trial of its timekeeping.

Using the a radio-controlled clock that receives the MSF time signal, the accuracy of the speaking clock was confirmed and then used to determine to going of ‘Clock B’. We determined that the clock was showing UTC -1/4 second.

The clock will be observed throughout the trial using the above method as well as being continually monitored by a Microset and GPS as well as the environmental conditions inside the case (temperature, humidity and barometric pressure).

The trial is intended to prove that this clock is the most accurate mechanical clock with a pendulum swinging in free-air in existence. Throughout the trial I will be blogging and posting updated videos to youtube, which you can subscribe to.

To wrap up this exciting experiment we will be presenting the data collected, the current understanding of how the clock works and, indeed, why it works so well in a one-day conference at the National Maritime Museum on 18 April, 2015, which incidentally will mark the 3 year anniversary of Clock B’s stay here in Greenwich.

Details of the programme will be announced shortly.

New lease of life for a distinguished old gent

This post was written by James Nye

Featured in James Bond’s Skyfall in 2012, the former Port of London Authority building near London’s Tower Hill is undergoing significant change, to become luxury apartments and a hotel, badged 10 Trinity Square.

The building was opened in 1922 by Lloyd George, and its boardroom hosted a reception on 30 January 1946 in honour of the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, which had commenced earlier in the month ( The Times , 31 January 1946, p. 7).

The boardroom was recently the focus for dramatic renovation works, with original surfaces being repaired and refinished.

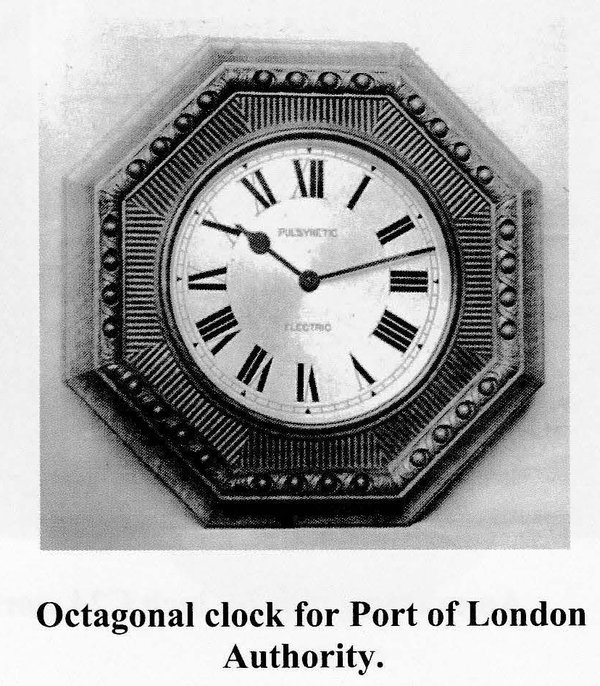

One relic from an earlier incarnation of the building to which the new owners turned their attention was the Gent Fig. C423 insertion feature clock, mounted in a panel above the balcony doorway.

This model was designed for the Festival of Britain in 1951. It is therefore clearly a later replacement of the movement first installed in 1922, but Colin Reynold’s excellent Conspectus of Clocks and Time Related Products Produced by Gent & Co Leicester (Leicester, 2011) illustrates the original pattern.

The current orphaned dial has lost the rest of its network of C7 master clock, and perhaps a hundred dials that might once have populated the building’s many rooms.

Johan ten Hoeve of The Clockworks was asked to attend to see what could be done to make it work.

Apart from the required servicing of the movement, the obvious solution was to provide a small self-contained master clock mechanism, quartz-controlled and battery-driven, to be hidden inside the panelling.

This parsimonious and relatively inexpensive solution has ensured the retention of a historic clock, in its original setting, and without the replacement of any parts. The old Gent lives to fight another day.

A 68 minute weight – with verisimilitude!

This post was written by Jon Colombo

At West Dean College, first year clock students make a hoop and spur wall clock from scratch. As far as practicable we use techniques available to an eighteenth-century clockmaker. This gives the deepest understanding of the mechanics, aesthetics and the way historic clocks are put together. Verisimilitude is important, but not critical. When making driving weights, students usually use brass tube, topped, tailed and filled with lead. As a former archaeologist, I wanted more authenticity.

Examining a selection of old weights showed:

- The joints do not seem to be soldered. Under a microscope, often the seam is marked by a thin copper-coloured line, likely to be loss of zinc from the brass.

- The joints are not brazed. It is common for the skin to split along the joint. Were they brazed, failure here would be very rare.

- Often the lead has shrunk away from both sides and hanger, leaving a hollow tube running down into the weight.

- The bottoms are almost always domed.

The first two suggest a butt joint. The third that the lead is stuck to the skin. It could be just the filling holding the whole thing together. Cooling shrinkage cooling would pull the skin into compression, and explain the need for domed base. The logic was convincing; time to try it.

I cut a skin and domed base of thin brass sheet, tinned and wired them tightly together. I then embedded the shell in sand and poured in lead.

Manufacture is simple, quick, economic – sheet formed on bar, butt joint filed, wired up and ready to go; hanger made from old wood screw.

The results were pleasingly close to the originals. The lead bonds firmly to the walls, heating them enough for the outside to take on a copper colour. In cooling the lead pulls the joint tight and forms the right shrinkage patterns. When I cleaned the weight, the copper colour was often left in the now very tight butt joint.

If you fancy giving it a go, or are simply curious, http://westdeanconservation.com/2014/06/05/a-68-minute-weight-with-verisimilitude/ gives a bit more detail.

War time reflections

This post was written by James Nye

The June centenary of the Archduke’s assassination is behind us, though in July 1914 no one imagined a world war breaking out a month ahead (head to the LMA for a great new exhibition).

In May, my talk at Greenwich—‘Bang on Time’—focused on 1940s clockwork devices used for delaying explosions, and it seems quite a few of my blogs dwell on bombs and destruction. Today, I reflect on some horological titbits from the Great War.

For a start, patriotism (and then conscription) emptied out light engineering and clockmaking firms of their young workers.

Of the 450 staff at Smith & Sons (MA) Ltd, floated in July 1914, nearly 10 per cent were at the Front a month later.

Silent Electric’s Herbert Bowell confirmed to the authorities in March 1917 that all his employees had signed up in 1914.

His better-known brother George, by contrast, was a munitions worker—the path for many other craftsmen.

After the ‘Shell Crisis’ of May 1915, resources poured into shell and fuze-making capacity, with the result that millions were crafted, to be fired on the battlefields of Europe. Though military demand for chronometers and timekeepers of all sorts mounted rapidly, clock and watchmakers from Clerkenwell were packed off to the north-east to work in firms such as Vickers, to manufacture fuzes.

While the factory workers and the soldiers they supplied are long gone, their products endure.

A standard artillery fuze might delay firing the main charge by up to half a minute. Precise (and expensive) fuzes had a clockwork escapement (see video) while vast numbers were simply igniferous, though even then involving a dozen or more precisely machined parts.

These remarkable engineered brass mementos regularly emerge from the soil a century later, and will still strip down.

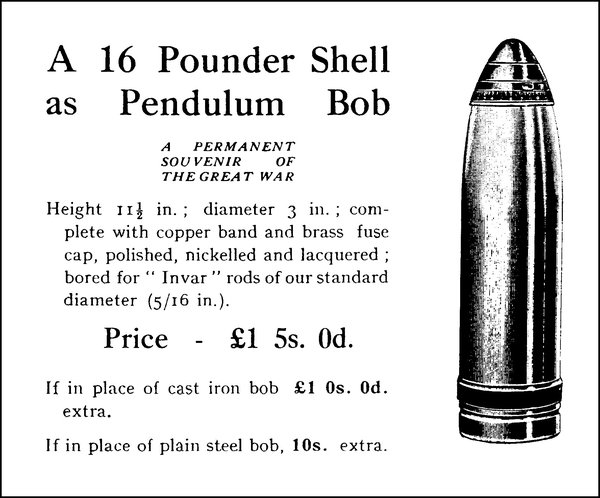

While surplus shell cases formed myriad household ephemera for years – Trench Art – another astonishing survivor was courtesy of the clock trade itself, in an idea from the irrepressible Frank Hope-Jones, who purchased 16-pounder shells (and fuzes), offering these as a pendulum bobs—a ‘souvenir’ of the Great War. What a blast!

Unreliable public clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

You only have to walk around in your own town to observe that of all the public clocks you pass by, only a few tell the correct time. Many show just any time, others have stopped working altogether.

Last year, a tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Guardian suggested that it was ‘time for a public clock tsar, with power to demand that owners restore their timepieces to reliable service’.

Here I learned of the existence of the blogspot Stoppedclocks, which invites us to ‘help find and fix all the stopped public clocks in Britain’. So if you have a particular gripe about a faulty clock in your area, you now know where to turn to.

There is, of course, nothing new under the sun. More than three centuries ago a correspondent to a London newspaper ventilated his gripe about the unreliability of public time-pieces.

It is quoted here, with the numbers referring to the map, as published in an article by Anthony Turner entitled ‘From sun and water to weights: public time devices from late Antiquity to the mid-seventeenth century’, published in Antiquarian Horology in March 2014.

![Details from John Roque, Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark…, 1747. The eastward route of the correspondent of the Athenian Mercury, and the nine numbered locations, from Covent Garden [1] to the Royal Exchange [9], are indicated in red (click on image to expand it)](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/map-of-London2.width-600.jpg)

'I was in Covent Garden 1 when the clock struck two, when I came to Somerset-house 2 by that it wanted a quarter of two, when I came to St. Clements 3 it was half an hour past two, when I came to St. Dunstans 4 it wanted a quarter of two, by Mr. Knib’s Dyal in Fleet-street 5 it was just two, when I came to Ludgate 6 it was half an hour past one, when I came to Bow Church 7, it wanted a quarter of two, by the Dyal near Stocks Market 8 it was a quarter past two, and when I came to the Royal Exchange 9 it wanted a quarter of two: This I aver for a Truth, and desire to know how long I was walking from Covent Garden to the Royal Exchange ?'

(Quoted from The Athenian Mercury, vi no 4, query 7, 13 February 1692/93).

Changing times in Germany

This post was written by David Rooney

We call it British summer time, but the first country to advance its clocks during the summer was Germany, which inaugurated a daylight-saving scheme in April 1916.

A letter, written 100 years ago this week and found buried in a museum archive, holds an important clue as to how the idea reached the top of German government just days before the outbreak of the First World War.

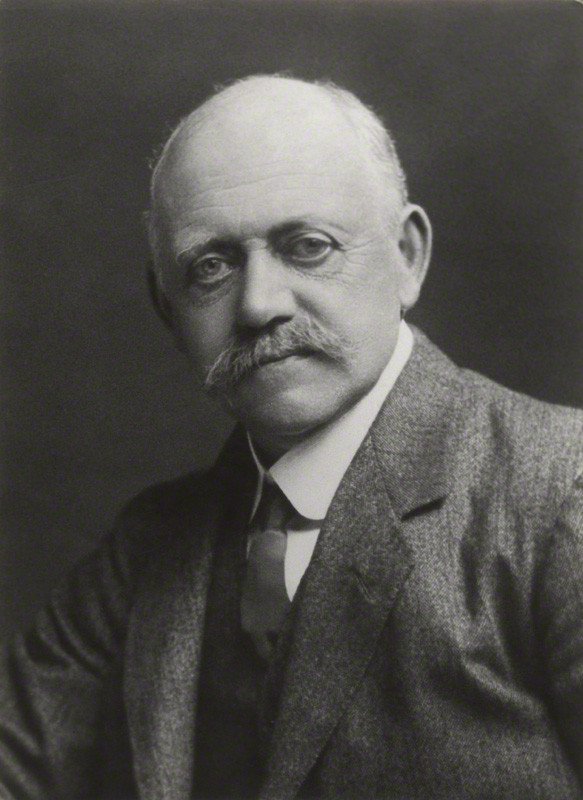

The champion of daylight-saving, British house-builder William Willett, had spent many years campaigning around the world for his time-shifting scheme to be adopted, and had become a regular correspondent with Henry von Böttinger, a prominent German chemist and industrialist who had been appointed to the Prussian House of Lords in 1909 by the German Emperor, Wilhelm II.

In 1913, von Böttinger had written to Willett to say that he was 'still pushing the Time Saving Question' and had raised the matter with the Prussian Minister of Public Works and the Association of German Chambers of Commerce.

But it was on 21 June 1914 that von Böttinger wrote again to Willett, this time with news that he was about to take the daylight-saving proposal to Germany’s highest authority.

'I have meantime taken note of your wish to have the subject laid before the German Emperor—and as His Majesty knows me personally and very well, I have at once made a written report to him and have asked him to devote his interest to the furtherance of this great object. As soon as I have another personal interview with His Majesty I shall not fail to bespeak the subject with him and thus bring the matter still closer home to him.'

Seven days later, Kaiser Wilhelm’s friend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated, and Europe began its plunging descent into war.

This was the last letter William Willett received regarding his international daylight-saving campaign, and a few months later, while on a business trip to Spain, he contracted influenza and died.

We will never know the full circumstances of Germany’s adoption of daylight saving time in 1916, but it is possible that this letter between two influential international businessmen represented the crucial turning point in Willett’s campaign—though it was a campaign he did not live to see realized.

What is certain is that technology and politics are inseparable: ideas need powerful backers, and the German Emperor in 1914 was truly one of the most powerful men in the world.

Keeping in touch with time

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

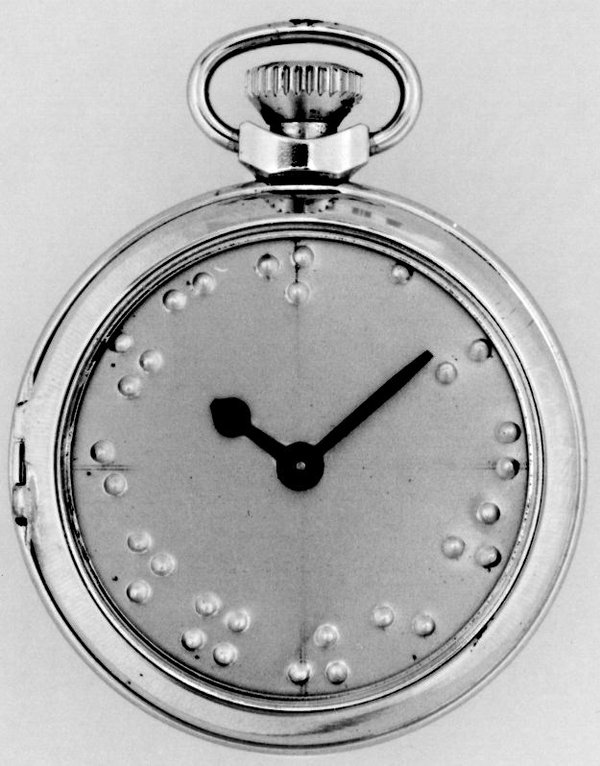

A common feature of watches and clocks of the 16th century are touch-pins. These are raised studs located at each hour position on the dial, with that at the 12 o’clock position typically being longer and sharper to provide a point of reference.

These enable the time to be read by feeling the position of the single, robust, hour hand.

This was useful as it was not possible to simply switch on a lamp to read the time at night. An added benefit might have been that the time could be read discretely under one’s robes.

This is a later variation of touch indication, known as a “montre à tact” (“touch watch”).

The exposed hand does not turn with the movement but it is moved manually, clockwise, until it stops at the right time. This is read against touch-pins that are located on the edge of the case.

These watches are also sometimes known as “blind-man’s” watches but, although they could have served as such, they were conceived as night watches.

This watch, however, was clearly designed to be used by visually impaired persons as it has Braille numerals on the dial.

Mass production of watches and clocks became established in the 19 th century and it enabled them to be affordable to the masses and, subsequently, the massive new market enabled a much greater variety to be economically viable, including this Braille watch.

This wrist-watch bears the latest incarnation of touch indication.

The time is indicated by steel ball bearings which run in tracks, positioned by magnets driven by the movement within the case – the hours around the perimeter and the minutes on the front of the watch.

The balls are easily displaced, which prevents damage to the movement, but are easily relocated with a twist of the wrist.

The watch was conceived for use by visually impaired persons, but its elegant design appeals to a far larger market. The development of this watch somewhat parallels that of the Braille watch, as it also depended on a fundamental development in technology and economics.

This watch was brought to market through internet “crowd-funding”, whereby many individuals invest a relatively small amount each to raise the total capital necessary to fund the development of a product (in this case enabled by Kickstarter). Crowd-funding can enable some exciting projects to succeed which might have been rejected by more traditional investors.