The AHS Blog

Happiest days of your life?

This post was written by James Nye

Recently we hosted the BHI North London branch at The Clockworks. It was a great visit, filled with observations and anecdotes about life among clocks.

Always popular, we looked at the Gent’s 'waiting train’, or ‘motor pendulum’. A neat design, synchronised to an accurate source, it has the power to overcome harsh winds or snow impeding the hands, compensating with more frequent impulses when needed.

Chatting over a coffee, stories emerged of people’s introduction to clocks and watches – particularly electric ones.

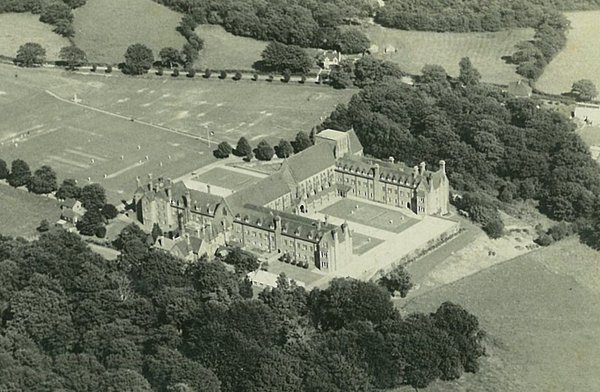

I described how, at the age of 13, I was put in charge of my school’s Gents-based clock system (for the nerds, C7, C69, C150 etc), including a waiting train in a tower above. One guest mentioned that coincidentally it was the same for him – being asked to tend to just such a school system.

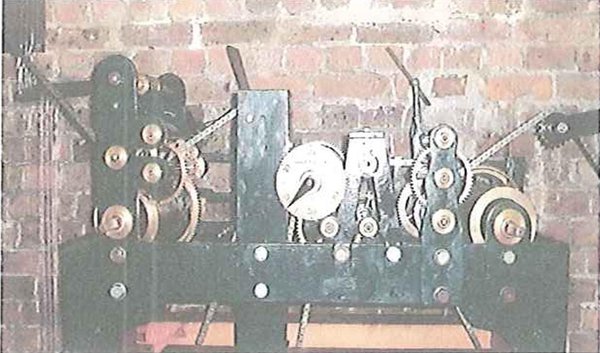

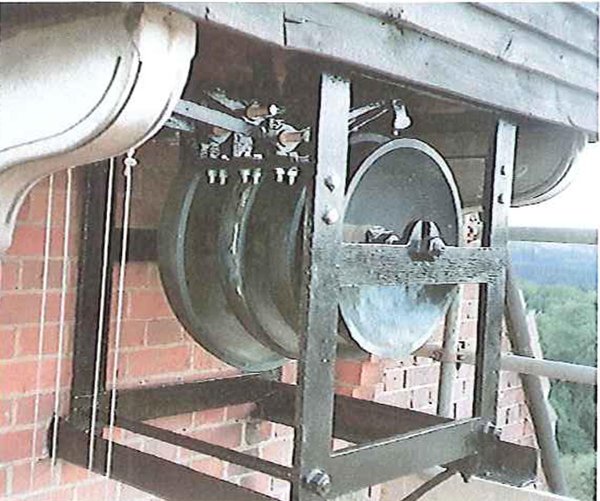

This prompted me to describe a feature of the system I maintained. A flatbed turret clock (David Glasgow, 1911) provided a chime and strike on bells, tripped by a solenoid, in turn controlled from the waiting train, using four aluminium sails (like a windmill) mounted on the bevel nest, operating each quarter on a microswitch – an ingenious addition.

‘Which school was this?’ asked a misty-eyed guest. ‘Ardingly College’, I replied. ‘That was me,’ he said softly, ‘probably in 1950.’

A quarter century apart, we had both been responsible for the same system. George D’Oyly Snow, headmaster, was fed up with chimes sounding at the wrong time, and with limited funds, but knowing the inventive skills of his boys, he commissioned my guest to find a solution – a solution still functioning into the late 1970s.

A theme I mentioned in a recent lecture is the serious risk to which electric clock systems are subject when their caretakers or installers move on.

The Ardingly Gent system, probably in service since the 1930s, was replaced after approximately 60 years by a radio-controlled master clock, and Thwaites & Reed recently reworked the flatbed movement, installing motor-wind, and even synchronization.

George Snow can rest easy in his grave – the chimes still sound on time. But to my mind they must sound a plaintive note as well – curiously, I feel desperately cheated of part of my heritage, and I know someone else who probably feels the same way.

Clocks in opera

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

If you like music as much as horology (I do!), this is for you. For the links to YouTube you need a loudspeaker or headphones.

In Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi, the eponymous court jester hires an assassin to murder his employer, a plan that goes horribly wrong. He meets up with the assassin at midnight (‘mezzanotte’), punctuated by twelve strikes of the turret clock. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 46mins 20sec).

![Rigoletto: ‘The clocks strikes midnight’ – scored twelve times for the camp[ane], the tubular bells in the orchestra](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/bells-in-Rigoletto-Final-Act-1.width-600.jpg)

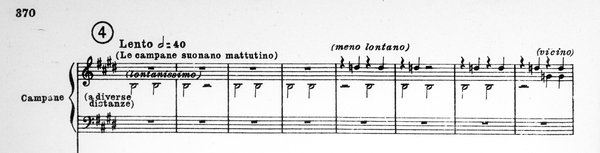

In Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca, Rome wakes up with the church bells sounding matins (early morning service). The instrument used in the orchestra is the tubular bells or chimes, metal tubes of different lengths hung from a metal frame, struck with a mallet.

The chiming is heard for more than two minutes, some bells sounding near, others in the distance. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 35mins36 sec).

Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov has a famous scene in which the Russian tsar has visions of the child prince he is suspected of having murdered. This is popularly known as the ‘clock scene’ and as there is no clock on stage nor in the text, this must relate to what goes on in the music.

Indeed, an obstinate, repetitive see-sawing theme is heard in the orchestra, but does it signify chiming or ticking? I am not sure. Watch it here (drag the timer to 0.58 for the ‘clock’ to start).

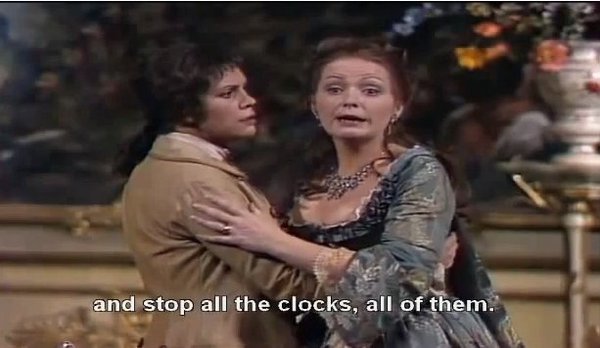

The most striking (pun intended) appearance of clocks in opera that I know is in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. An aristocratic lady has an extra-marital affair with a much younger man (sung by a mezzo soprano, one of the classic ‘trouser roles’ in opera).

Musing on how one day she will lose her young lover, as with the passing of time her charms will fade, she sings about the nature of time:

'Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding. Wenn man so hinlebt, ist sie rein gar nichts. Aber dann auf einmal, da spürt man nichts als sie. Sie ist um uns herum, sie ist auch in uns drinnen. In den Gesichtern rieselt sie, im Spiegel da rieselt sie, in meinen Schläfen fliesst sie. Und zwischen mir und dir da fliesst sie wieder, lautlos, wie eine Sanduhr. Oh, Quinquin! Manchmal hör’ ich sie fliessen – unaufhaltsam. Manchmal steh’ ich auf mitten in der Nacht und lass die Uhren alle, alle stehn'

or;

'Time is a strange thing When one is living one’s life away it is absolutely nothing. Then suddenly one is aware of nothing else. It is all around us, and in us too. It trickles across our faces, it trickles in the mirror there, it flows around my temples. And between you and me, it flows again, silently, like an hourglass. O, my darling, at times I hear it flowing – inexorably. At times I get up in the middle of the night and stop all the clocks, all of them.'

The music comes to a stand-still and all you hear is the chiming of a small domestic clock, played in the harps and the celesta – it’s magical. Watch it here sung in original German, with subtitles; drag the timer to 0.19.

Fine timing

This post was written by Paul Buck

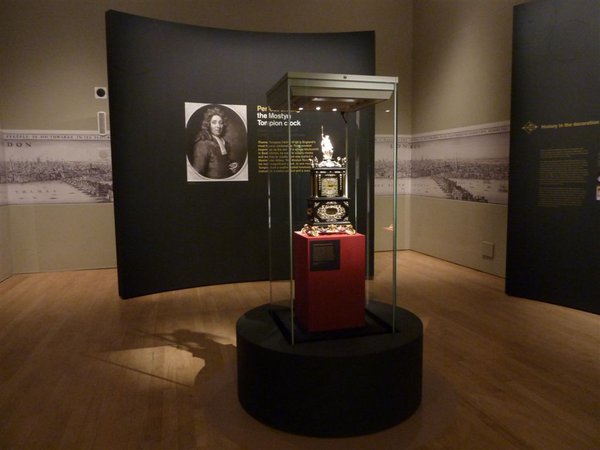

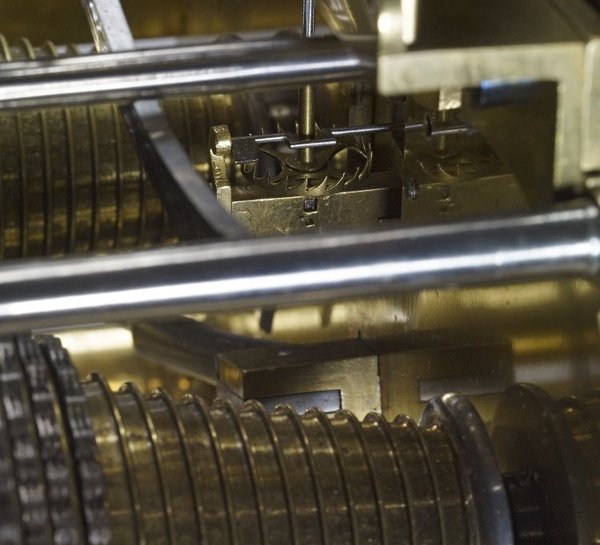

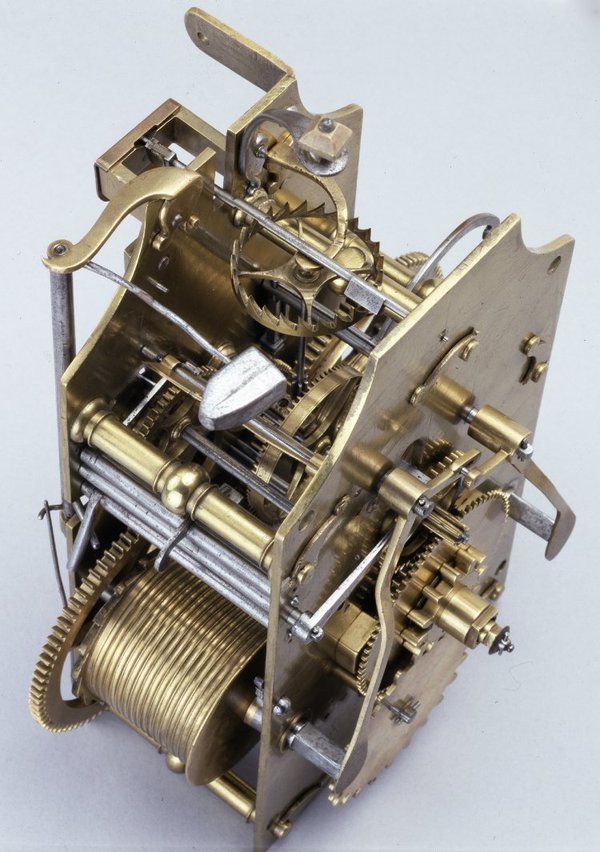

A new exhibition has opened in Room 3 at the British Museum displaying the year going table clock by Thomas Tompion. This magnificent clock celebrates the coronation of William III and Mary II in 1689, and was kept in the royal bedchamber. It was made by a talented and industrious man who was in the right place at the right time.

Tompion’s modest beginnings as the son of a Bedfordshire blacksmith are recorded, but after that nothing is known of his whereabouts until he appears in London at the age of 32.

Wherever he had come from, he was extremely well trained in the making of clocks and watches.

London 350 years ago was the ideal place for Tompion’s genius to shine. In the previous century, religious persecution in the Netherlands and France had led to an exodus of Protestants, including many goldsmiths, silversmiths, engravers and watchmakers who established their trades in London.

Despite the Great Fire and the plague that preceded it, 1670s Restoration London was prosperous, with a plentiful supply of wealthy clients to support the burgeoning clock and watch trade. The new accuracy in clocks resulting from the application of the pendulum in 1657 followed by the balance spring in watches in 1675 was of great interest.

When William died the clock passed to Henry Sydney, Earl of Romney, Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Groom of the Stole. On his death in 1704, it passed to the Earl of Leicester and then to Lord Mostyn and remained in that family until 1982.

It is now known as ‘the Mostyn Tompion’ after its former owners.

The clock continues to keep good time, and is notably ‘year-going’ – it runs for over a year on a single wind. It also strikes the hours, an annual total of 56,940 blows on the bell.

This free exhibition is timed to coincide with the 300th anniversary of Tompion’s death in November 1713 and runs until 2nd February 2014.

If only I knew what the right time is

This post was written by David Thompson

When you want to know the correct time today, you either look at your mobile phone or you look at your radio controlled clock watch or listen to the six pips on the radio. However, don’t do the last one on digital radio as it is quite a bit out of sync with the real time – about two seconds.

Before the introduction of telegraph time signals and the distribution of time, everyone had to rely on a local observation of true solar time – that is, the time shown on a sundial.

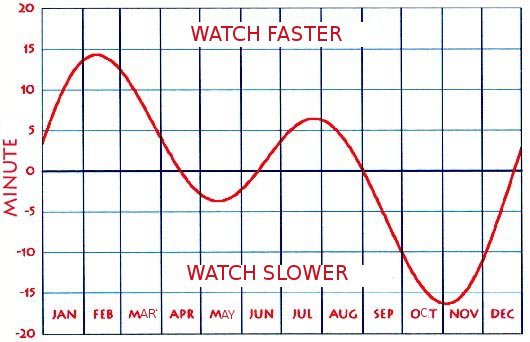

Unfortunately, the mean time shown by a clock and the true time shown by a sundial don’t agree throughout the year. Because the earth’s orbit around the sun is elliptical and because the earth’s axis is tilted to the celestial plane by 23 ½ degrees, the sundial (showing apparent or true solar time) and the clock (showing mean solar time) can be different by as much as 15 minutes.

There are four days in the year when the clock and the sundial agree with each other – 15th April, 13th June, 1st September and 25th December.

Until 1657 and the introduction of the pendulum, real time didn’t matter much as clocks were so inaccurate that the variations between true and mean time were irrelevant to all except astronomers.

The application of the pendulum to clocks made them capable of much more accurate timekeeping and the same was true when the balance spring was added to the watch in 1675 – measuring time to within a minute a week.

So, in order for an owner to put his clock right by a sundial, he had to know what the difference should be between his sundial reading and the time shown on his clock.

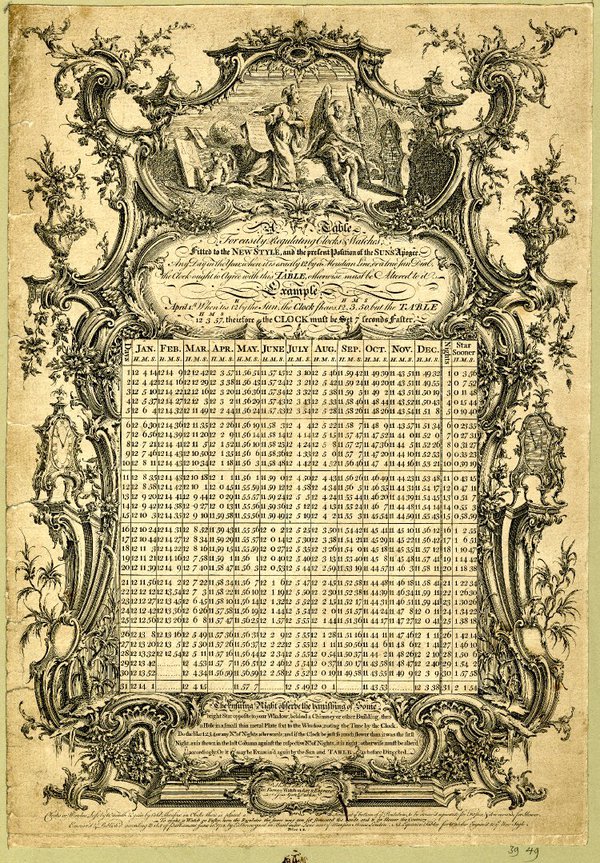

From the latter part of the seventeenth century, tables were published which gave exactly that information. The table shown here is devised so that when a clock is checked at noon, the table shows what time the clock should show.

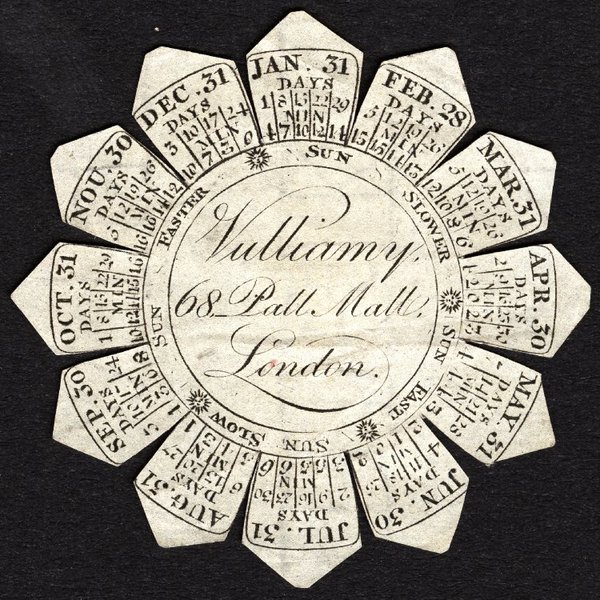

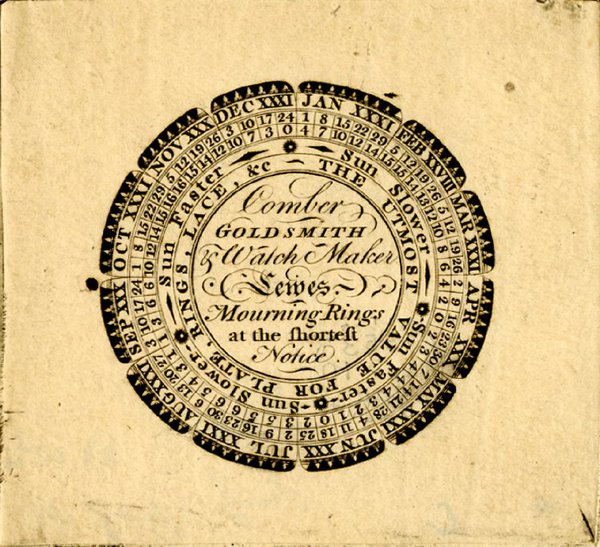

From the later part of the 18th century watchmakers would add a circular advertising paper into the outer cases of pair-cased watches and many of these had the equation-of-time table printed on them for easy reference.

Such papers were produced by top London makers such as Vulliamy in Pall Mall and by provincial makers such as Richard Comber of Lewes in Sussex. It was probably Comber’s customers who needed a table more than someone in the centre of London where the church bells offered a huge variety of ‘right’ time. It is worth bearing in mind, too, that the adjustments could only be done when the sun was shining!

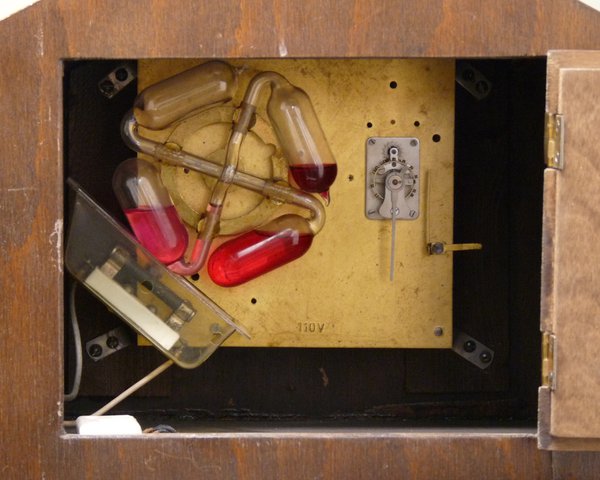

Freak control

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Continuing our wander through the five elements, we come to the controller – the part of the clock which controls its rate. Let us pass-by the major landmarks (the pendulum, the balance spring and wheel and the quartz crystal) and seek an alternative trail.

With their origins preceding mechanical clocks, compartmented cylindrical clepsydrae (shown in a previous post for their silent operation) have a drum which rotates and descends. Water passes between compartments inside the drum, controlling the rate of rotation.

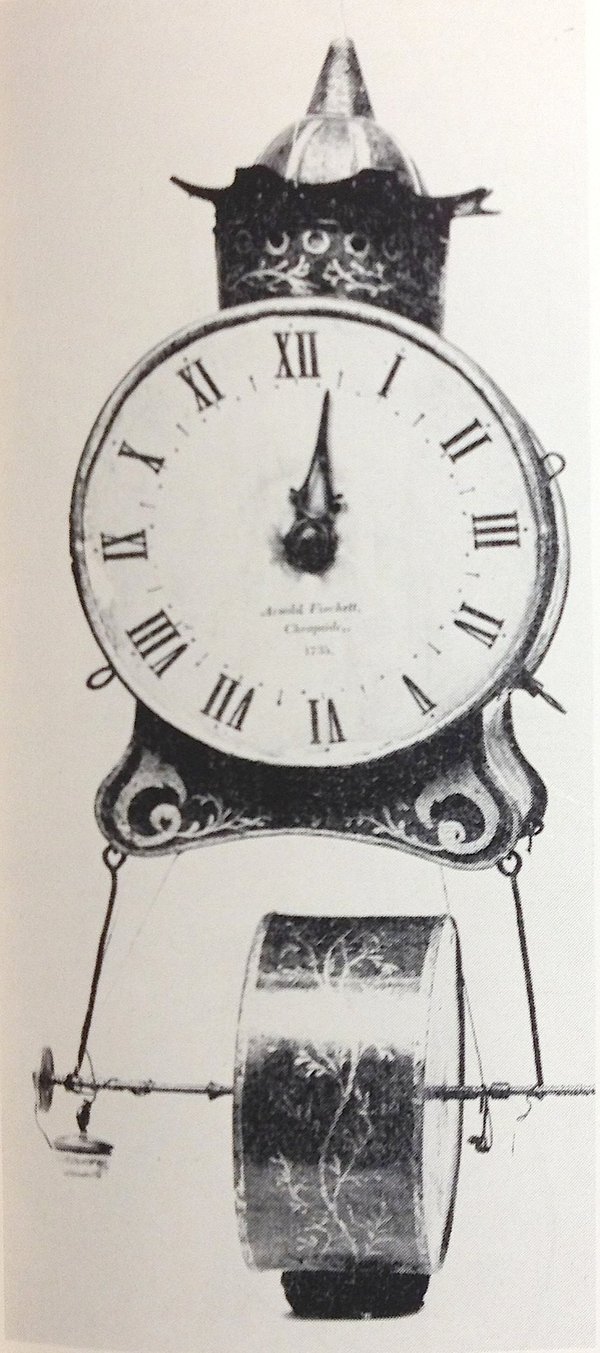

These were recurrently popular at various times in history and were incorporated in clocks, such as the example illustrated here which was made by Arnold Finchett, London, c.1760. The drum, connected by a line, drives the hand on the dial. This system is reported to provide reasonable timekeeping (at least in non-freezing conditions)!

Sir William Congreve (1772-1828) patented his inclined-plane rolling-ball clock design in 1808. Its ball bearing zigzags down a track on the table and actuates a lever at the end of its travel, causing the table to see-saw and the ball to roll back again.

In the example illustrated here, each leg takes thirty seconds. Despite being largely detached from the influence of the movement, the progress of the ball is hampered by any irregularities on the track, generally resulting in awful timekeeping (rather like my daily commute).

Nevertheless, the clock is mesmerising and surveys show that it retains the attention of visitors longer than any other exhibit in Djanogly horological galleries.

Another clock shown before is the Smiths “Sectric” electric mantel clock. The clock motor is synchronous – i.e. its speed depends on the (very stable) frequency of the alternating current of the mains supply, which thus effectively controls the rate of the clock.

These clocks were very popular from 1930s but were superseded by quartz technology from the late 1960s, largely for the convenience of battery power, which avoided the need for wiring.

Finally, from 1960 Bulova produced their 'Accutron' watches which incorporated a tuning fork to control their rate. The steady hum of the tuning fork can clearly be heard when the watch is held to the ear.

Despite being excellent timekeepers and very popular, within ten years the introduction of superior and cheaper quartz watches rendered them obsolete.

Falling back

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

It’s that time of year again when our faithful timekeepers quiver, for fear that we will ignore the advice of the clockmaker and attempt to turn the hands backwards, as we return to daily life punctuated by GMT (or UTC if you prefer) on Sunday.

I think it is fair to say that the majority of us are more sympathetic towards the autumnal adjustment, as we can luxuriate in the hour that was ‘banked’ in the spring, so perhaps now is the ideal time to bring this discussion to the AHS blog.

Today, internet searchers will find that the energetic equestrian builder from Petts Wood, William Willett has been eclipsed as the architect of Daylight Saving Time (DST) by George Vernon Hudson, the English born New Zealand entomologist, who first proposed his scheme to the Wellington Philosophical Society in 1895.

In England, thanks to Willett’s monumental efforts, the Daylight Saving Bill was presented before parliament in 1908 and it offered that ‘for a period of 154 days, an increase of sixty minutes more sunshine in the evening of each day’.

The then President of the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill astutely noted in the margins of his copy that this was an ‘optimistic view of our climate!’

Despite Churchill’s support the Bill did not pass and it was eight years before Daylight Saving was introduced as a wartime economy pre-empted by its earlier implementation in Germany.

This Sunday, as you pause the pendulum on your antique clock, will you follow Winston Churchill’s lead and ‘raise a silent toast to William Willett’ and perhaps reflect on the 154 hours of extra ‘sunshine’ that you enjoyed this year?

Conservation and repair of a mystery clock

This post was written by Kenneth Cobb

A disassembled glass and ormolu mystery clock was sent to West Dean College from overseas to be reassembled. A simple enough request, however the 1850’s mechanical mystique of smooth running remained a challenge throughout the three month process.

The clock was made by Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. Born into a family of watchmakers in Blois, France, he was primarily a conjurer and practical joker and this clock is no exception as it is Robert-Houdin’s ‘Fourth Series’ of Mystery Clocks. Onlookers would have wondered at the science of telling the time without the hands being attached to conventional clockwork.

One of West Dean’s key strengths is that conservation departments work together, thus the glass was cleaned by students in the Ceramics Department and advice on cleaning the ormolu was supplied by the Metals Department. Typical of the West Dean conservation approach is Robert Houdin’s signature in copper plate writing on a plate, which was left with the patina as received since it is stable.

The movement itself was a challenge as previous repairs had probably exacerbated its primary weaknesses: the plates are long with a minimum number of pillars to support the tensions of twin sprung barrels thereby making the movement unstable. The lead-off work was hidden within the body of the object. There were so many interconnected links that it was not clear which connection or link was at fault: a question that took weeks to resolve.

Finally, the clock ran reliably and sadly had to be returned as it was a considerable source of interest. As a student, the clock was been a privilege to work on having been a great source of learning and patience, and under the tutorship of Matthew Read and Malcolm Archer I have gained a lot more understanding and confidence in this field.

Can we sex-up the time-recorder?

This post was written by James Nye

We’re used to seeing Hollywood actresses, the latest haute horlogerie on their wrists, gazing at us in dreamy soft focus. But what about the advertisers looking to push horlogerie industrielle?

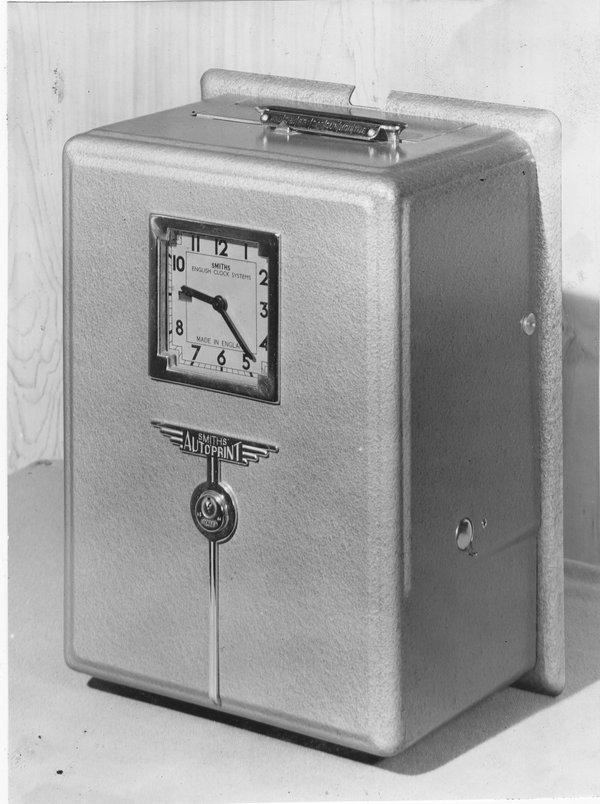

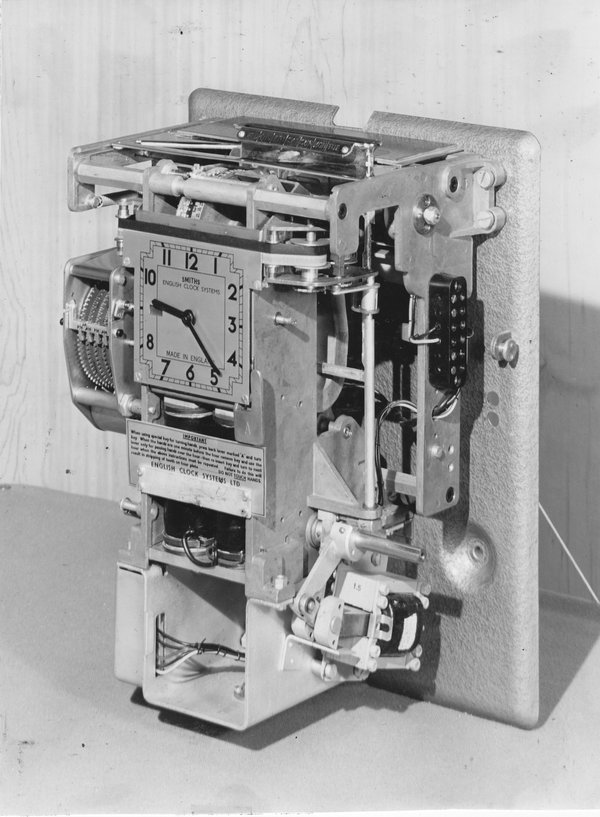

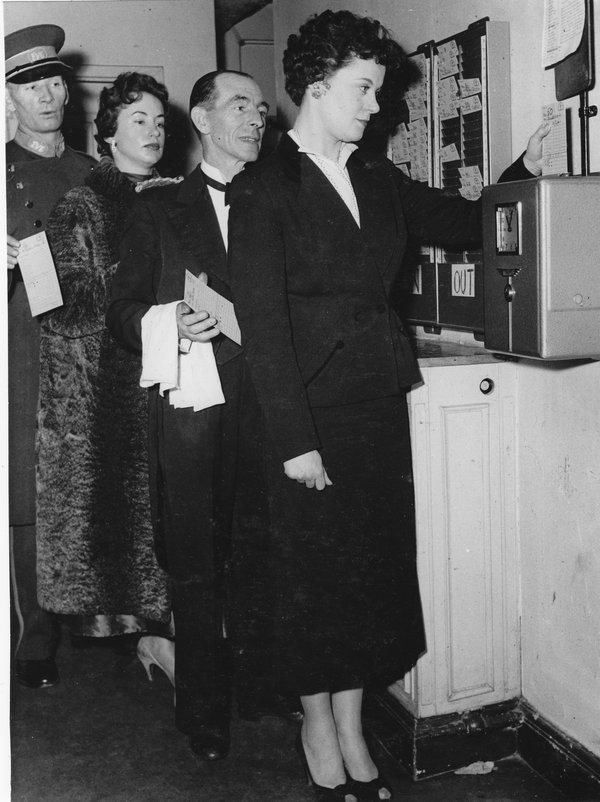

In an earlier blog I presented some pictures from inside the English Clock Systems (ECS) works at King’s Cross from the early 1950s. One of the shots showed the production line for the time recorders. The final product – the Autoprint – was a superb machine, and here are a couple of shots, showing both the mechanism and the outer casing.

The problem facing the ECS publicity unit was how to make the machine a bit more interesting in a catalogue or journal report. Watches and exotic locations were one thing, but the time recorder presented a bit of a challenge on the face of it. In this blog I speculate on the thought process of the lads as they set to their task.

The Autoprint was proudly on show at the 1956 British Industries Fair. The display stand was duly photographed, but an attraction for businessmen that year was a trip to the Eve nightclub on Regent Street. Our intrepid team tagged along, and lo and behold, the nightclub staff used an Autoprint!

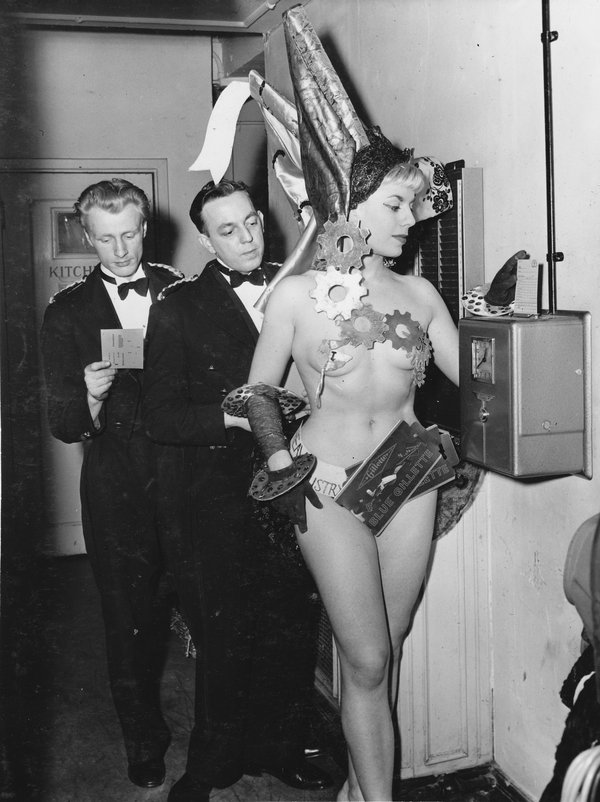

A first shot caught the commissionaire and other colleagues stamping their cards, but patience was rewarded with the arrival of a hostess, happy to pose.

Finally, of course, the show-girls themselves arrived – all adorned with representations of items manufactured in Britain. The third image shows Gillette-girl!

Picture Post (7 January 1956) carried a double-page spread on the cabaret, illustrating different industries from the BIF, but the historic industrial horological shot shown here remained hidden in an archive until I stumbled across it recently. In the interests of scholarship I felt it should be published.

A silent turret clock at the V&A

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum who notice the turret clock high up in the entrance hall find no explanatory label. Fortunately there is detailed information on the V&A website.

The 8-day turret clock with hour striking was ordered in 1857 for the newly created South Kensington Museum, as it was then named. It was made by J. Smith and Sons of Clerkenwell and cost £150: £110 for the clock and £40 for the bell and fittings.

A duplicate of the clock was later made by the same firm and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1862 (held on the site of the present Natural History Museum), where it gained a prize medal.

The two dials were designed by the artist Francis Wollaston Moody, who decorated much of the museum, and show allegorical figures.

Day, in a chariot, is followed by a cloaked female figure representing Night; below it is the figure of Time with his symbols: hourglass and scythe. The irrevocability of time is represented by the letters of the word IRREVOCABLE spaced out between the Roman numerals.

To see it properly you need binoculars, but the photos reproduced here – as good as I could manage with a simple camera and amateur skills – give an idea of what the clock looks like.

In 1951 the clock was stopped and silenced, as it was cumbersome for a clock-winder to climb up a ladder, and the booming bell was thought a nuisance for the visitors. Later it was taken down and stored away.

But in the early 1980s it was put back in place, as it was considered an interesting object in its own right, and because of its association with the early history of the museum. It has been converted to electricity, so it shows the correct time even though the pendulum with its heavy spherical bob hangs motionless. But the bell remains silent.

'A Visit to the Science and Art Museums'

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1932, the Trinidadian historian and writer, Cyril Lionel Robert (C.L.R.) James, then aged 31, visited the Science Museum in London.

'I hadn’t intended to spend much time there', he wrote. 'I was on my way to the Victoria and Albert Museum. But one of the men I was with, John Ince, is clever at engines and, at least to an ignoramus like myself, learned in the mysteries of mechanics. He persuaded me to go in and, I do not know why, the place had a surprising effect on me.'

The museum had only been open in its present building on Exhibition Road for some five years when James visited. He was, as he described, 'knocked silly' by the sight of a racing seaplane in the front hall, 'one of the most beautiful things I have seen in London.'

But after James had viewed the Science Museum’s aircraft collection, he made his way to the time measurement display and stood gazing at the huge clock from Wells Cathedral, constructed in 1392 and moved to the Science Museum in the nineteenth century where, he observed, 'it ticks serenely on, striking the quarters and the hours, and keeping much better time than the brand-new watch which I bought two weeks ago'.

Standing in front of this iconic clock, James was struck by a feeling of mortality. 'I had a good look at that old clock', he remarked. 'I couldn’t help remembering with envy that in a few years I would probably be gone, while the old beast would probably be there in a thousand years, tick-ticking away, living his narrow but peaceable life.'

It was not until 1989, 57 years after his visit to the Science Museum’s clocks gallery, that C.L.R. James finally passed away, aged 88, in a small flat in Brixton. He had achieved many great things in his momentous life. But he was right: the Wells Cathedral clock keeps on tick-ticking at the Science Museum, over 600 years since it was first set going. And it still offers attentive visitors pause for thought, as it did in 1932.

Turret clock specialist Keith Scobie-Youngs will be speaking about the Wells Cathedral clock (together with other ancient timekeepers) at the AHS London Lecture Series on 20 March 2014. Check the AHS website nearer the time for more details.

Wake up – tea’s up

This post was written by David Thompson

What a treat to be able to wake up in the morning to a ready-made cup of tea and to be grateful to a machine for producing it automatically. Many of the older generation will remember a machine for just that purpose, a machine which was always referred to as the Teasmade.

Probably the one we all remember was the Goblin Teasmade but there were many others and the originally idea has its origins at the end of the 19th century with Mr. Rowbottom’s 1891 patent – with an automatically lit gas burner to heat the water in the kettle and then the machine would pour the boiling water into a tea-pot to make the tea, I can just see the warning notice on such a machine today – well not really as such a fire hazard would not be put into manufacture today.

There is a fine example of an Albert E. Richardson machine in the Science Museum to give an idea of what the early machine were like.

I was intrigued by this subject from seeing the Teasmade on exhibition in the British Museum clocks and watches gallery and it lead me to a splendid account of the history of the automatic tea maker written by David Stoner and published as a chapter in Clifford Bird’s book on Metamec, published by our own society and still available today at a give-away price.

All the original machines were clockwork, controlled by a simple alarm clock mechanism so you got the wake-up bell and the ready-made cup of tea, almost guaranteed to be luke warm. Many people swore by them and I don’t doubt at them. Nevertheless, a great idea.

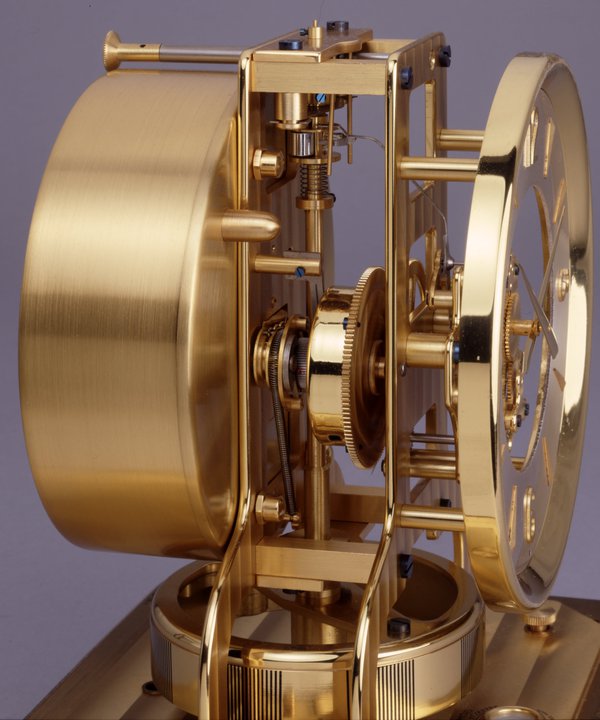

Time and efficiency

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Last time I looked at how clocks and watches obtain and store their energy, but I thought it worth mentioning how carefully they use it.

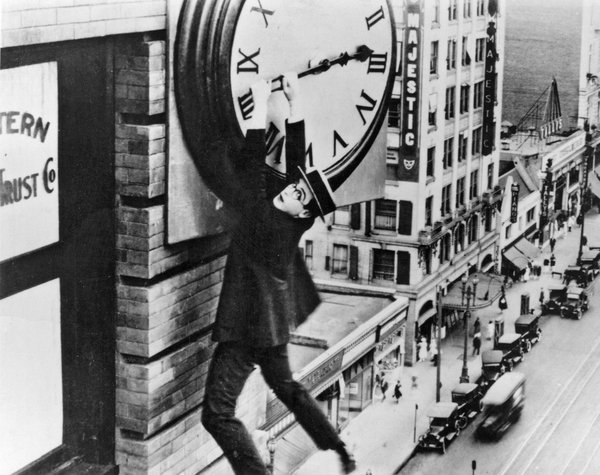

Some clocks are designed to have a surfeit of energy – for instance turret clocks must be able to overcome ice and snow loading. But, in general, efficiency is paramount in horology.

A 17th century eight day longcase clock typically runs on a 12lb weight (5.44kg in new money) which drops about 5 feet in the eight days. Based on those numbers, my dimly recollected school physics tells me that such a longcase clock must use about 1/8500th of a Watt of power.

Let us compare that with something familiar. The best example I can think-up is the motor that vibrates a mobile phone – these run at about 0.16W – i.e. that little motor that tickles in your pocket could run about 1500 longcase clocks. Or, looking at it another way, the energy used to boil an egg would keep a longcase clock going for 80 years. Not bad for a 300 year old machine.

The Atmos clock (which I mentioned before for its ability to be powered by changes in air temperature) is in another league – the little mobile phone motor could run 700,000 of them. 1 boiled egg, 38000 years.

How are they so much more efficient than the longcase clock? Apart from being closer in scale to watch work, the Atmos clock benefits from 250 years of horological development. They are factory made, not hand made – this facilitates much closer tolerances and optimal gear tooth shapes. Like fine watches, their bearings are jewelled (jewels are little rubies with holes drilled in them – very smooth and very hard wearing). They also have a steel torsion pendulum which is excellent at conserving energy.

Something else to bear in mind is that we expect our clocks and watches to run non-stop for years on end, between services, without breaking down. Do you ask the same of your car? Remember that when your clock repairer presents their next bill to you!

Home time

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

As next year’s AHS conference will be shaped by the theme ‘Military Time’, it seems appropriate that this post should follow the military theme and by chance, as with David Read’s recent post, it includes a radio.

There are two HS.4 navigational watches in the National Maritime Museum collection, both retailed by the firm H. Golay and Sons, which were used by the Fleet Air Arm in Fairey Swordfish aircraft during WWII.

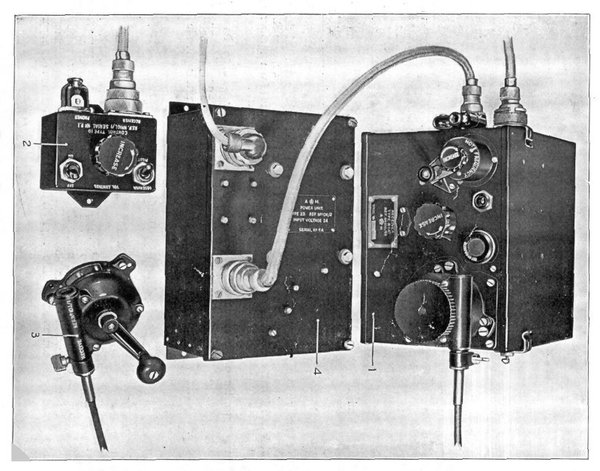

We learn from the 1941/1942 Admiralty Manual of Navigation that these watches were known as beacon watches and that they were only to be used in aircraft fitted with an R1147 radio receiver.

The carriers were equipped with a revolving beacon that continuously transmitted second pulses, making a full rotation once per minute. The crucial feature of this system was that the beacon emitted a different sounding signal when it was pointing due north. Prior to launch (these planes were catapulted into the air) the observer would tune the radio receiver to the beacon and set the bezel of the watch so that zero on the outer scale and the tip of the second hand align precisely at the time of the northern signal.

When returning to the carrier, the observer on board the aircraft would turn on the radio and listen to the beacon’s signal. The strongest reception would be experienced when the beacon was pointing directly at the aircraft and using the watch, the aircraft’s position relative to its carrier could be found and the pilot given the course to take.

If we take the watch shown above, for example, as indicating the moment of the signal’s maximum intensity, the aircraft’s position would be approximately SSW of the carrier. The primary benefit was that these slow aircraft could home in on their carrier from up to 100 miles away without sending out radio signals that may betray their position to the enemy.

This ingenious horological adaptation helped to save lives and is just one example of innovation necessitated by war that could be explored at next year’s conference.

If you feel that you can contribute a talk that would fit ‘Military Time’ theme, you are invited to contact the AGM lecture coordinator, Rory McEvoy, Curator of Horology, Royal Observatory Greenwich, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SE10 9NF, e-mail: RmcEvoy@rmg.co.uk. Papers could explore technical horological development as well the wider implications for both civil and military timekeeping. Please note that the theme is not limited to the First World War, and that the military of course includes the ground, sea and air forces.

When is a wrist watch not a watch?

This post was written by David Read

In February 2013 it was leaked that Apple was experimenting with an iWatch. However, six months later and at the time of writing this blog there is still no news from Apple and the technical press is now guessing that the project has hit battery problems.

If only Dick Tracy, the famous cartoon sleuth, was still around to find out what the bad guys are up to and get at the iWatch facts. Tracy had sported a remarkable watch on his wrist since 1946 and now, 67 years later, Time Magazine described that watch as 'the most indestructible meme in tech journalism'.

For decades now, it has been nearly impossible to write about communications technology combined with a wristwatch without invoking the plainclothes cop with a special watch on his wrist who first appeared in 1931, even though the days when one could follow Dick Tracy’s adventures in a daily newspaper have long gone.

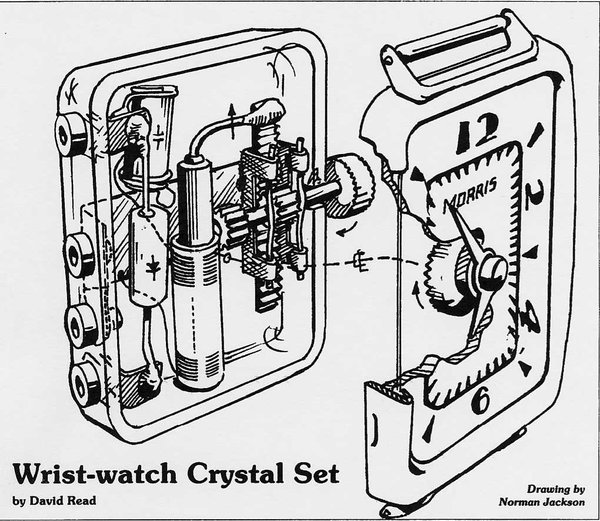

Popular science fiction is always years ahead of the technologies that turn dreams into reality. However developments in solid state electronics had, by the 1940s, enabled the large galena and cat’s whisker detector of the crystal set to be produced as a tiny point-contact diode and placed inside a wrist watch case as in the Morris watch shown here.

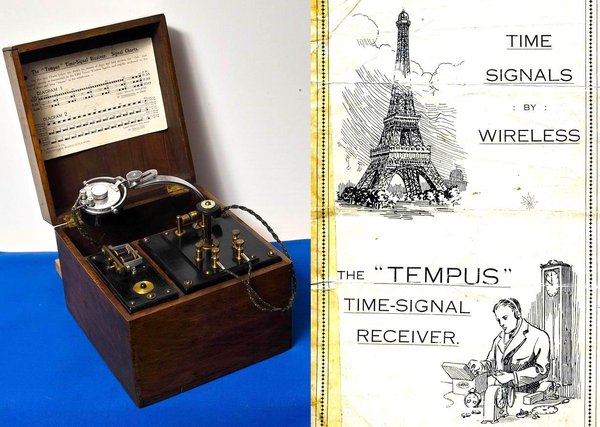

But is this a watch? No, it’s a crystal radio. However, horology and radio have a long shared history involving frequency and time. This clandestine wristwatch radio can receive time signals in exactly the same way as mariners and watchmakers did from 1912 in order to check their chronometers, clocks and watches against the timecode transmitted from the Eiffel Tower. My image of the Tempus crystal radio and instructions sets the scene.

The illustration of the Morris watch shows a standard-sized watch case made of chrome-plated steel. The dial, signed Morris, is in typical 1940s style. The standard of manufacture is high and the disguise on the wrist is perfect. The case back is made of moulded Perspex to provide an insulated chassis on which the circuit can be built without special measures to insulate the components, aerial, earphone sockets and associated wiring.

The winding button is actually a dial knob and connects to a rack-and-pinion control of tuning in which an iron-dust core is moved within the aerial coil and tunes the required frequency by altering the coil’s inductance. This assembly is connected to the earthy end of the coil and also to the metal case thus providing a body earth to stabilize the circuit whilst tuning. A tiny sealed point-contact crystal detector is enclosed in an evacuated glass tube and a capacitor across the coil completes the circuit.

A second pinion on the winding stem connects with a crown wheel on which the hands are mounted. This alters the position of the hands on the face of the watch and provides a scale against which a station can be memorized or noted. Using the wrist watch crystal set in conjunction with a deaf aid as an amplifier would have allowed the use of a short aerial such a bedstead and completed the disguised operation.

The drawing was made for me in the 1980s by my late dear friend Norman Jackson, an outstanding engineer and artist whose illustrations always showed at a glance how things work; something that photographs can never match.

It is interesting to speculate why such a radio was made and I have never seen another. However, the Morris watch cannot be unique because it is a professionally designed object requiring bespoke production tooling and Perspex moulding facilities. The public market for such clandestine receivers would have been tiny and with no chance of recovering the costs involved. Without a consumer market for this item it would seem possible that it was funded by a government agency and the headline news today shows that such agencies are still active in the ancient arts of listening, spying, and gathering information.

And another thing – yes it does work!

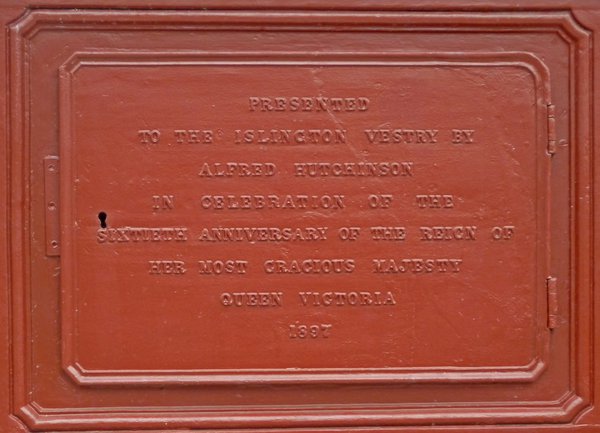

Clocks and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Cycling through north London I like to pass by the Jubilee Clocktower at Highbury, Islington, near the Arsenal football stadium. It was erected in 1897, sixty years after Queen Victoria came on the throne. And in the March 2011 issue of Antiquarian Horology we published a photo of a jubilee clocktower at East Harptree, Somerset, taken during one of the regional excursions of the AHS Turret Clock Group.

These are just two of what must have been dozens, perhaps hundreds, such clocktowers that bear witness to the commemorative zeal of the late Victorians. In February 1897, a specialist firm issued the following circular letter intended to generate new orders:

'We desire to draw the attention of the Nobility, Clergy, Gentry and others, who are contemplating the erection of Church and Turret Clocks in commemoration of the Diamond Jubilee of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, to our unrivalled facilities for manufacturing all kinds of clocks at the lowest possible prizes consistent with good workmanship and material, and to all requiring the same we would be glad to furnish estimates and information free of charge.'

Quoted from Michael S. Potts, Potts of Leeds. Five Generations of Clockmakers (Mayfield Book 2006), p. 133.

Many orders came in. The smallest clock tower that Potts installed in 1897 stands, fourteen feet high, on the town square of Much Wenlock, Shropshire.

Wikipedia has a list of jubilee clocktowers which also includes examples erected ten years earlier for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, like the one on the seafront at Weymouth, Dorset. They were also built in outlying parts of the British Empire. The Victoria Clocktower in Georgetown, Malaysia is still a well-loved landmark. It is sixty feet tall, one foot for each year of Victoria’s reign.

It would be great to have a proper study of these late nineteenth-century jubilee clocks and clocktowers, with a gazetteer telling us where they are, and of course who supplied the clocks. Something for a website, a book, or perhaps an article in Antiquarian Horology?

Walking the ‘Willett Way’

This post was written by David Rooney

Every spring, when we put our clocks and watches forward for British Summer Time, we do so with a hollow laugh. March weather is rarely summery! But last month many in the UK have seen prolonged sunshine, and in London we’ve had a heat wave. Summer arrived at last.

If you like walking in sunny weather, and if you’re in London, you can combine a walk with finding out more about British Summer Time. It takes in Petts Wood and Chislehurst, home of William Willett, the schemes creator, and it’s easily accessible by public transport.

You can view the walk instructions online or print them off. But I must warn you that it’s a while since I prepared this trail, and things might have changed. Do take care and, if in doubt, follow your common sense, not my instructions! One thing that changed since I wrote the walk is the refurbishment of Willett’s grave, now looking superb.

It fascinates me that twice a year, every year, quarter of the population of the Earth changes its clocks and watches for summer time. That is a real, physical, close engagement between billions of people and billions of timekeepers each year across the globe—all because a Victorian British house-builder and moralist thought we should get up earlier in summer.

What this shows is the sheer power of clocks and watches to change and order human behaviour—or rather, the inventive ability of people to use time to control other people. We can see it all over the place when we know what to look for. Time is a political tool.

And that is one reason why you should join the AHS. Knowledge is power, and the more we understand timekeeping, the more we can understand the control that people exert on our lives using it. PS I’ve recently joined Twitter. If you’ve nothing better to do, you can follow me @rooneyvision.

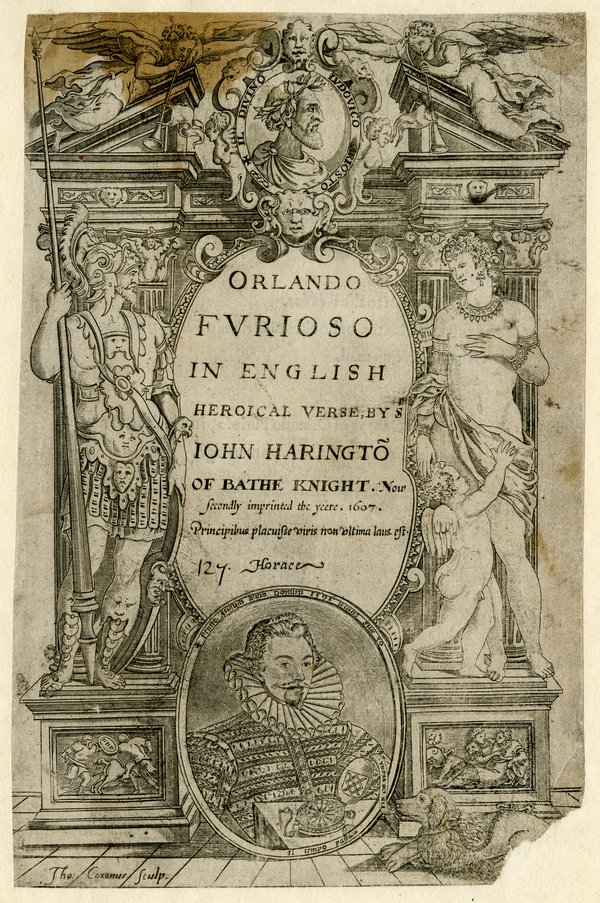

Just so you know how rich I am

This post was written by David Thompson

Today some people wear expensive watches partly to demonstrate their wealth. They either sparkle with diamonds or they impress with their complexity of mechanical magnificence. You might think that this is a new idea, but in fact this tradition goes back centuries to when the first watches were made in the early part of the 16th century.

An interesting example of this comes from the title page of Sir John Harrington’s translation of Orlando Furioso, (The Frenzy of Orlando, an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto first published in 1516.) Harrington’s translation, which appeared in 1591 was the first in English. The story contains politics, war, religion and unrequited love as well as fantasy and consists of forty-six eight-line verses in rhyme – quite a challenge for the translator.

On the title page of the work is an engraved portrait of Sir John proudly sporting a fine oval-cased watch with the Harrington shield of arms engraved inside the cover. The portrait is dated 1st August 1591 and bears the inscription ‘Il tempo passa’ and the legend that Sir John was thirty years old when the portrait was taken – time passes and this is a moment in the life of the author.

A similar watch can be found in the British Museum collections, made by an immigrant Flemish worker in London, Ghylis van Gheele and here too, the watch sports a shield of arms, This time of the Giffard family of St. Andrew’s Abbey in Northamptonshire.

In late Elizabethan England what better way to show everyone just how wealthy and successful you were.

Power madness

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

In a previous post I explained how mechanical clocks and watches work, with five elements – energy, wheels, escapement, controller and indicator. Let’s explore how some clocks and watches get their energy.

Mechanical clocks and watches employ kinetic energy, drawn from a built-in reserve – usually a mainspring (elastic potential energy) or a driving weight (gravitational potential energy). However, these need to be replenished, or wound-up.

We commonly wind-up a clock or watch directly, with kinetic energy from our muscles (which, before that, was chemical energy from our breakfast). In an automatic watch, a moving weight spins and winds it up as we move around.

In c.1765, James Cox made a clock that is wound by changes in atmospheric pressure. Similar is the Atmos clock, which has gas-filled bellows which expand and contract with changes in the surrounding air temperature and pressure – this movement winds the spring in the clock. This has been a very successful design – it was first introduced in 1928 and it is still being made. There was even a mechanical clock made to be powered by by an artificial heat source (see image).

Electrical clocks and watches employ electrical energy. We might provide this by putting in a fresh battery (which is a reserve of chemical potential energy), although sometimes the battery is rather larger than the clock it powers!

Mains powered clocks often do not have a built-in energy reserve and so these are reliant on a continuous supply to keep going. Solar powered clocks and watches use solar panels to convert light to electricity, which then charges a battery – this reserve is essential as the power source is not reliable – e.g. day and night.

So, those are a few examples of how clocks and watches can obtain the energy they need. Of all the types of energy I can think of, only sound and atomic energy have not been not used to directly power clocks and watches. As to how they exploit the energy… well that is another story altogether… maybe for a later post!

It’s for the birds

This post was written by James Nye

Some pigeon racers were cheats. This was the shocking brief given to the Skymaster Clock team in the 1950s when refining their latest patent racing clock.

It was a serious business for the 100,000 registered pigeon fanciers in Britain, and rigid standards were enforced. Defeating the few cheats involved some inspired horology, and when I heard how clever the solution was, I wanted to share it here. But first, let’s understand the basics.

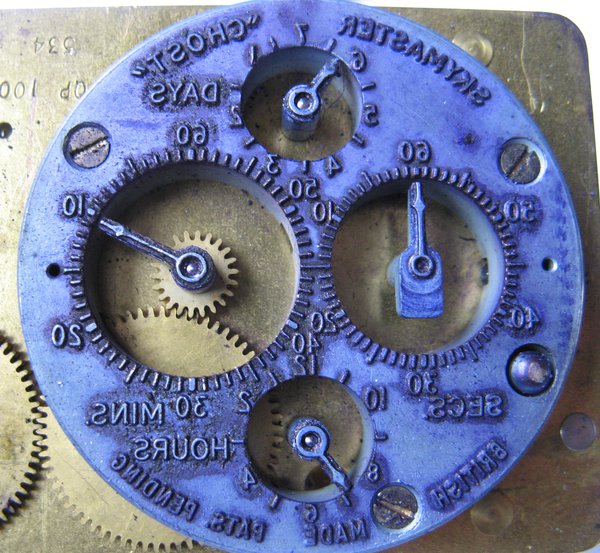

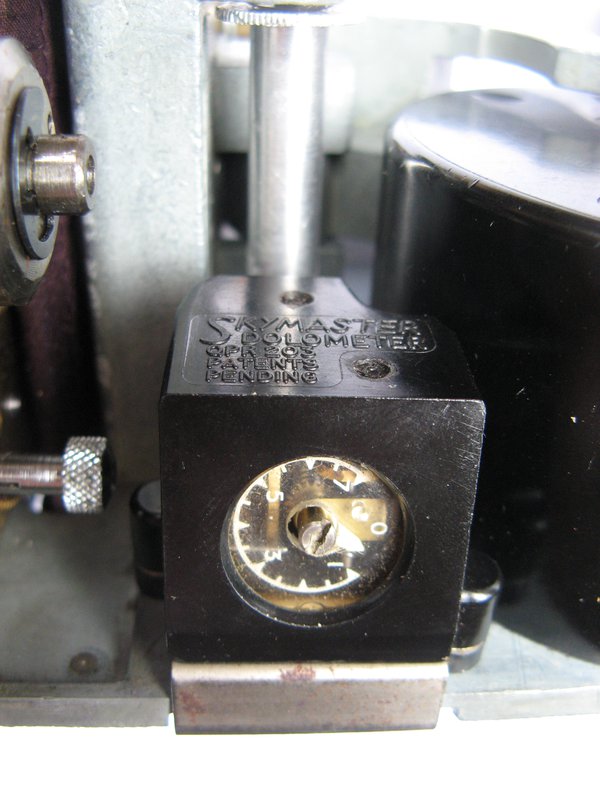

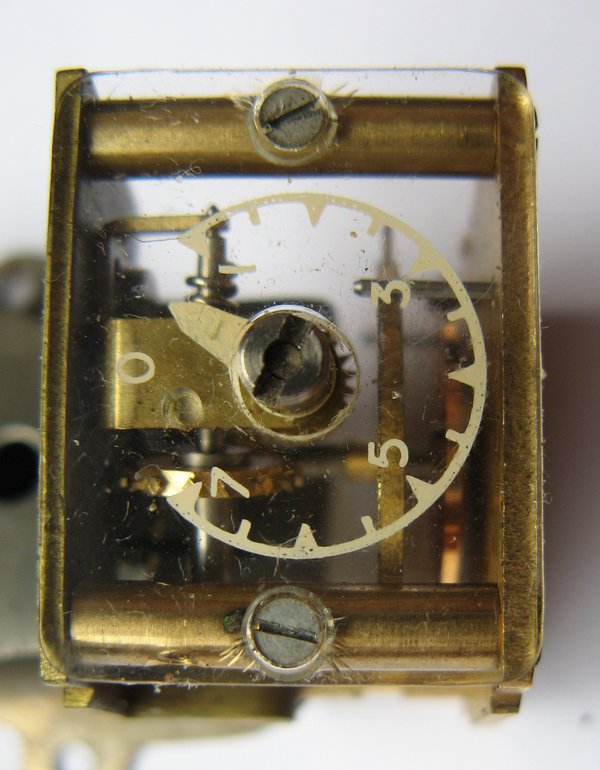

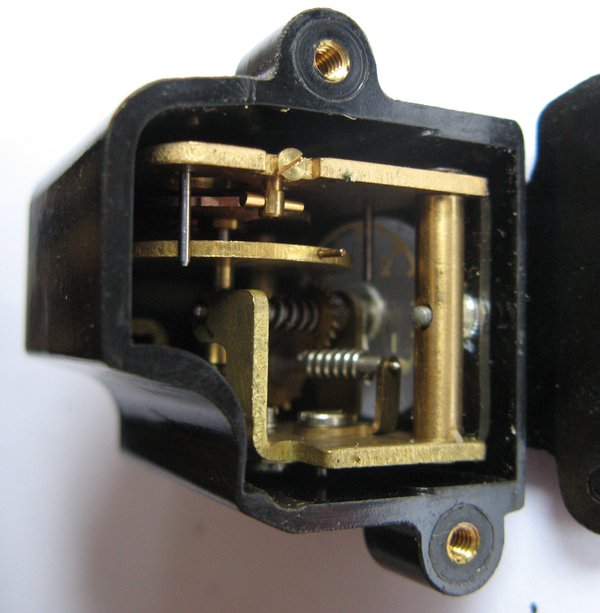

The Skymaster clock contains a 7-jewelled platform escapement movement, coupled to an inked ribbon stamping mechanism (like a time-recorder) which presses a paper tape against an internal mirror image dial (in relief), recording the time a returning pigeon’s identifying ring is inserted.

Races are won by seconds. Pigeon clocks are meticulously checked and every option to cheat is blocked. But unscrupulous fanciers had come to believe that platform escapement clocks could have their rates meaningfully altered, for example by swinging the clock in the same plane as the balance, so that they might both retard the locked clock (ideal before the pigeon arrives) and advance it (needed once the pigeon is back) to get it back to time before being examined by an official.

The effectiveness of these methods is uncertain but, nevertheless, Eric Moss and Bruce Alexander of Smiths were compelled to devise a brilliant solution for the Skymaster – called the ‘Dolometer’. They based it on an electro-mechanical car clock, in which typically an inverted-Sully escapement (electrically driven) advances the train. See an animation here. They removed the magnetic drive, and relied on the overall motion of the clock to drive the Dolometer – thus the dial reveals the degree of any shaking.

Calibrate for ‘normal’ activity (the natural joggling of a journey home to the loft, plus a margin for error) and if the Dolometer shows an excess, you have detected a naughty pigeon fancier’s attempted fraud. Bruce Alexander carried a dolometer for days – even cycled with it – to work out what a normal reading would be.

This seems to me to have been inspired thinking on the part of the designers. And it inspired me to acquire a Skymaster so that I could dismantle and photograph it for you.

Big Ben and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The iconic tower that houses the world’s most famous clock has always simply been known as the Clock Tower, but was renamed Elizabeth Tower to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. Will the name catch on? I think that the man in the street, and that includes the tourists, will continue to call it the Big Ben, even though that was never the name of the tower, just the nick-name of the hour bell.

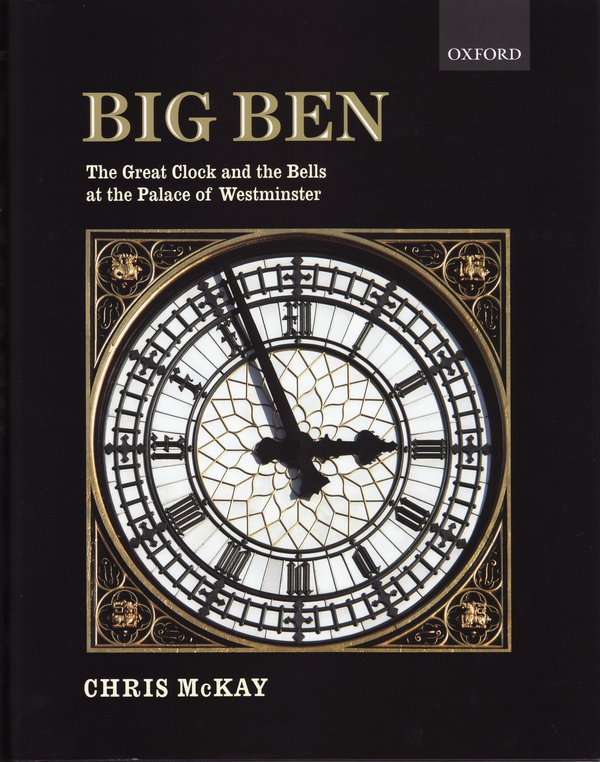

On 10 June I attended the launch of a guidebook published by the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and the Elizabeth Tower. It was great fun because it was held in the Palace of Westminster, in the opulent State Rooms in Speaker’s House, which outsiders don’t often get to see. The book is attractively produced and richly illustrated, and those wanting more can read Chris McKay’s book Big Ben. The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster.

Mr Speaker, John Bercow MP, addressed the guests, after which there were short talks by Mike McCann, keeper of the Great Clock, and Paul Roberson, one of the three clockmakers responsible for winding, servicing and repair of over a thousand clocks in the Palace of Westminster.

Between them, they also have to provide a 365 days a year out of hours call-out service should the Great Clock have a problem.

This illustrated article by Chris McKay reports on an overhaul of the Great Clock, undertaken in 2007 to correct wear problems. Paul Roberson, who is currently chairman of the British Clock and Watchmakers Guild, ended his talk with a joke that is probably as old as the hills but was new to me: 'What did Big Ben say to the Tower of Pisa? "I’ve got the Time, if you’ve got the Inclination".'

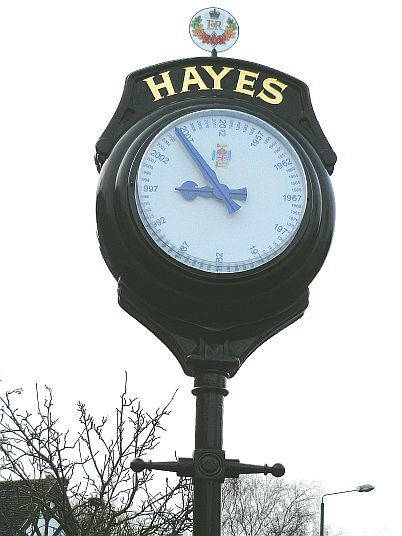

Elsewhere in the country the Diamond Jubilee has inspired modest horological activity. In February 2013 a jubilee clock was unveiled in Hayes in southeast London. The clock dial is made up of the sixty years of the Queen’s reign rather than minutes, with 2012 marking 12 o’clock.

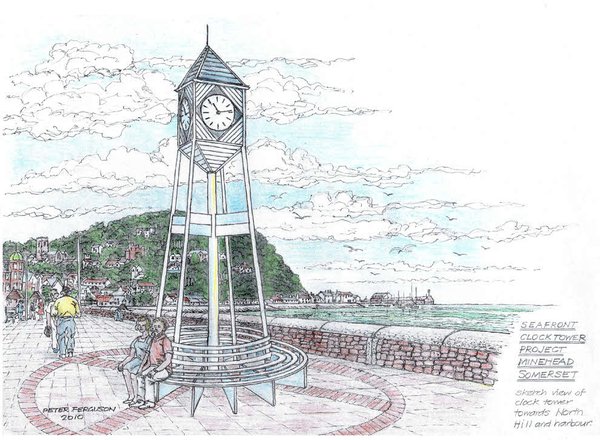

And in Minehead on the Somerset coast they hope to build an 8.5 metre tower with a four-sided display, with clocks on three sides and current tide times on the fourth. They still need donations to make it happen.

There will have been more initiatives. But it was nothing compared to the public clock ‘mania’ that erupted on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, which I shall discuss in my next blog.