Clocks in opera

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

If you like music as much as horology (I do!), this is for you. For the links to YouTube you need a loudspeaker or headphones.

In Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi, the eponymous court jester hires an assassin to murder his employer, a plan that goes horribly wrong. He meets up with the assassin at midnight (‘mezzanotte’), punctuated by twelve strikes of the turret clock. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 46mins 20sec).

![Rigoletto: ‘The clocks strikes midnight’ – scored twelve times for the camp[ane], the tubular bells in the orchestra](https://ahs.contentfiles.net/media/images/bells-in-Rigoletto-Final-Act-1.width-600.jpg)

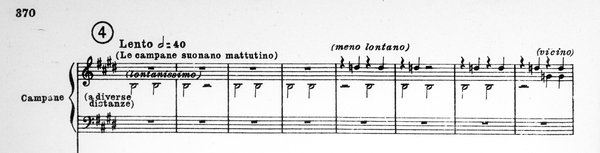

In Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca, Rome wakes up with the church bells sounding matins (early morning service). The instrument used in the orchestra is the tubular bells or chimes, metal tubes of different lengths hung from a metal frame, struck with a mallet.

The chiming is heard for more than two minutes, some bells sounding near, others in the distance. Watch it here (drag the timer to 1hr 35mins36 sec).

Modest Mussorgsky’s opera Boris Godunov has a famous scene in which the Russian tsar has visions of the child prince he is suspected of having murdered. This is popularly known as the ‘clock scene’ and as there is no clock on stage nor in the text, this must relate to what goes on in the music.

Indeed, an obstinate, repetitive see-sawing theme is heard in the orchestra, but does it signify chiming or ticking? I am not sure. Watch it here (drag the timer to 0.58 for the ‘clock’ to start).

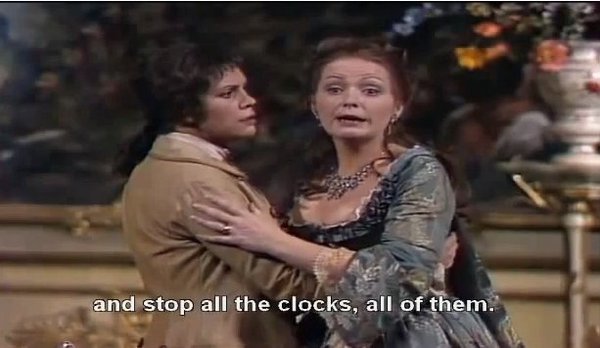

The most striking (pun intended) appearance of clocks in opera that I know is in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss. An aristocratic lady has an extra-marital affair with a much younger man (sung by a mezzo soprano, one of the classic ‘trouser roles’ in opera).

Musing on how one day she will lose her young lover, as with the passing of time her charms will fade, she sings about the nature of time:

'Die Zeit, die ist ein sonderbar Ding. Wenn man so hinlebt, ist sie rein gar nichts. Aber dann auf einmal, da spürt man nichts als sie. Sie ist um uns herum, sie ist auch in uns drinnen. In den Gesichtern rieselt sie, im Spiegel da rieselt sie, in meinen Schläfen fliesst sie. Und zwischen mir und dir da fliesst sie wieder, lautlos, wie eine Sanduhr. Oh, Quinquin! Manchmal hör’ ich sie fliessen – unaufhaltsam. Manchmal steh’ ich auf mitten in der Nacht und lass die Uhren alle, alle stehn'

or;

'Time is a strange thing When one is living one’s life away it is absolutely nothing. Then suddenly one is aware of nothing else. It is all around us, and in us too. It trickles across our faces, it trickles in the mirror there, it flows around my temples. And between you and me, it flows again, silently, like an hourglass. O, my darling, at times I hear it flowing – inexorably. At times I get up in the middle of the night and stop all the clocks, all of them.'

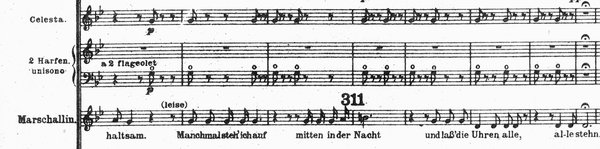

The music comes to a stand-still and all you hear is the chiming of a small domestic clock, played in the harps and the celesta – it’s magical. Watch it here sung in original German, with subtitles; drag the timer to 0.19.