…on the other hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have simple, easy to use, single-handed dials. On the other hand, some dials are not so straightforward.

This clock has 'fly-back' or 'retrograde' hands. The hands proceed clockwise as usual but when they reach the end of the scale, each will spring back and then immediately resume its count.

This design allows the dial to have twice the diameter of a circular dial within a given height. This, together with the semi-circular form, makes these clocks suitable for positioning over doorways and they were sometimes integrated within wall panelling.

Fly-back hands are still a popular feature in watches, although these are usually (but not always) the preserve of high-end watches.

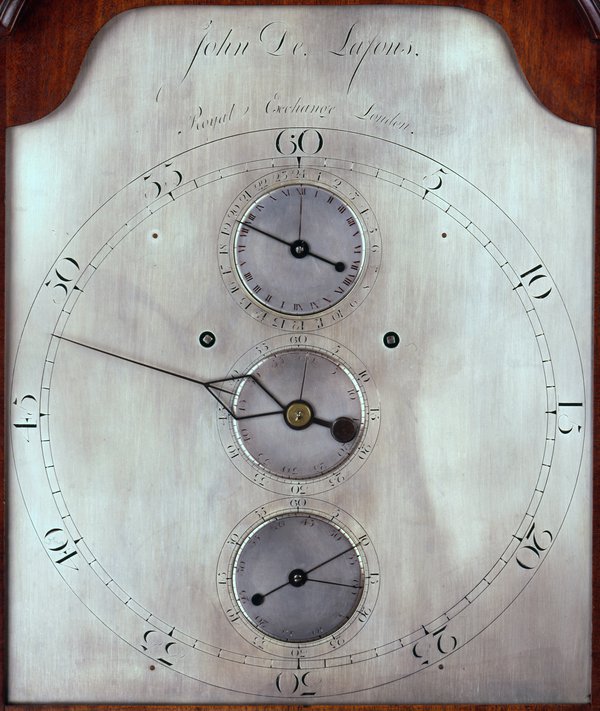

The dial of this regulator (that I have mentioned before for its escapement) has the typical features which facilitate the use of these clocks in observatories and laboratories. All hands are positioned on their own centres for disambiguation. The hours are relegated to a small subsidiary dial and only the minutes have a large hand, for accurate observations.

Less typically, however, this regulator indicates two different systems of time using only one set of hands.

It shows mean sidereal time against the numerals on the main dial plate and mean solar time against the small discs. A mean sidereal day is 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds, i.e. it is about 4 minutes shorter than the 24 hour mean solar day. The discs rotate slightly faster than the hands so that after each day they have accrued the 4 minutes difference. This system is called a differential dial.

Having a clock show both sidereal and solar time might have been a convenience, but a respectable observatory might well be expected to have had separate regulators for providing the required times and so it is possible that this design may have been conceived rather for the use of the (wealthy) amateur.

This watch has not just hands, but arms and fingers too! It is a type of watch known as “bras en-l’air”, which translates as “hands in the air” (and certainly not “bras in the air” – which might apply another aspect of horology altogether). When the pendant is pushed the soldier raises his arms, holding pistols to point at minutes (left) and hours (right).