The AHS Blog

The conservation of precision horology

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A few weeks ago I attended a fascinating international three-day conference on the conservation of historic regulators and chronometers, hosted by the curatorial and conservation staff at Palermo Observatory in Sicily, part of the INAF group (Instituto Nationale di Astrofisica) of Italian observatories, all of which have historic collections of instruments and timekeepers.

The lectures, which were presented by specialist curators and conservators from Italy, UK, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, covered a great range of horological subjects from philosophical preservation, practical conservation of collections and a more general discussion of the care and preservation of these especially vulnerable objects.

Although the various papers reflected quite different perspectives, all the speakers found common ground on the principles of care and spoke with one voice on the aims of their roles as custodians of our historic collections.

A particular aim of the conference, discussed in depth in the final group meeting, was to formulate a common set of guidelines for future curators and conservators, and an internet forum was then established to continue the dialogue in future.

The hosts at Palermo Observatory, Ileana Chinnici and Maria Carotenuto, to whom we were especially grateful for organising the event, were particularly keen to seek advice from delegates on formulating a programme of care for the fine collections at Palermo. This might then apply to all the historic precision instruments in the Italian observatories under INAF.

We learned some fascinating statistics:

-- these instruments represent 80 per cent of the astronomical heritage in Italy, and 10 per cent of these objects are timekeepers of one kind or another;

-- in all the various observatory collections there are 53 clocks, 31 chronographs and 12 box chronometers;

-- 25 per cent of the horological material is of British manufacture, 20 per cent is Swiss, 13 per cent is Austrian/German, 7 per cent is French, and 35 per cent is Italian.

Naturally the regulators at Palermo formed the focus of much interest and discussion during the conference, and what fine things they are! The stellar list of makers includes Mudge & Dutton, Janvier, Vulliamy, Cumming & Grant, Frodsham, Dent and Riefler.

Palermo Observatory had been founded in 1790 with Guiseppe Piazzi as its first astronomer. It was Piazzi who, on a visit to London and Paris in the late 1780s, commissioned the regulators from Mudge & Dutton, Cumming & Grant and Janvier as the first timekeepers for astronomical use at Palermo.

Having recently studied and written about the works of Alexander Cumming (Antiquarian Horology, March 2022), I found the example by Cumming & Grant, which has Cumming's own form of gravity escapement, of particular interest. It is very similar to the regulator signed by Grant only, in the Clockmakers' Company Museum in the Science Museum, London, both clocks being of superb quality.

A really interesting and valuable three days; there will hopefully be a chance to return soon to study this fine collection more closely.

The various rooms in the historic building now form the museum of the observatory, which can be visited in person or virtually.

John Harrison and the Board of Longitude go digital

This post was written by Richard Dunn

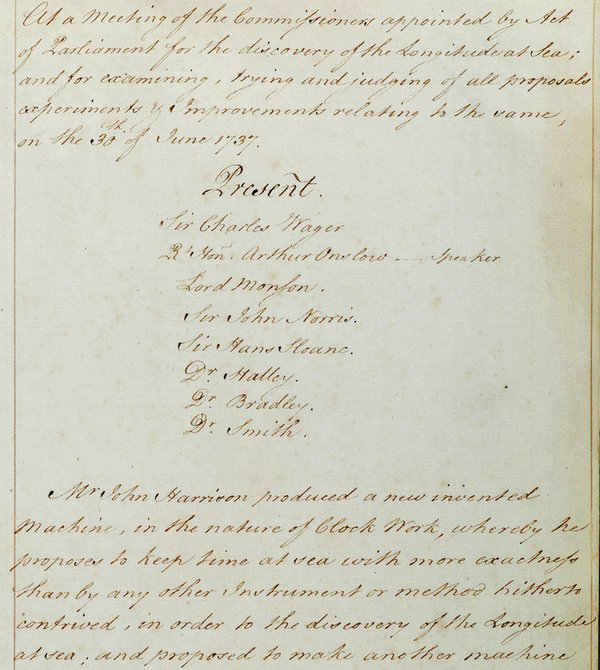

Last week, the Cambridge Digital Library launched some samples of material from the Board of Longitude archive that will interest anyone wanting to know more about John Harrison, the Board of Longitude and the development of timekeeping at sea (among many other things).

Three volumes from the Board’s archive have just been put up: the first volume of confirmed minutes (1737-1779), which includes a full transcription and covers all the meetings involving John Harrison; William Wales’s log from James Cook’s second voyage (1772-75), on which Larcum Kendall’s first marine timekeeper (K1) was tested alongside three by John Arnold; and a group of letters and reports by astronomers and captains from late-18th and early 19th century voyages of discovery.

For all three volumes, there are also links with the collections at Royal Museums Greenwich.

The trial launch is part of a JISC-supported project, ‘Navigating Eighteenth Century Science and Technology: the Board of Longitude’. This is a collaboration between Royal Museums Greenwich and the University of Cambridge that is going to digitise all the surviving archives of the Board of Longitude and related material in Greenwich and Cambridge. The remaining material will go online during the summer of 2013.

The project team would like to get feedback on how the current version works and things they can do to improve it. There should be lots of interesting stuff in the three volumes now online, so please have a look and leave any comments via the feedback function on the Cambridge Digital Library.

Waking up with a bang

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

In my own time I am Adviser to the National Trust on the care and curatorship of their clocks and watches, and occasionally the Trust’s Advisers on different disciplines are called upon to work together.

Clocks and Firearms might seem an improbable combination, but one object in the Trust’s collections recently brought me and Brian Godwin (Adviser on Firearms) together for a most interesting study day.

Snowshill Manor, a house full of surprises, was, almost inevitably, the source of the object in question – a little gilt-brass table clock with alarm, made about 1740 and signed by Peter Mornier, London. The Trust has any number of clocks with alarm mechanisms, but this particular example has an additional feature, guaranteed to have the owner out of the deepest slumber in a trice.

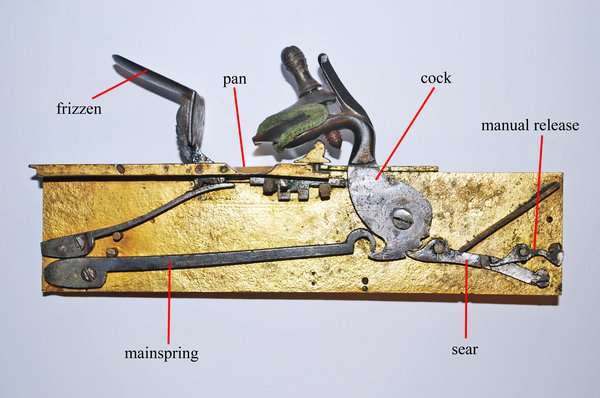

As with most alarm clocks of the period, the clock sounds a bell at the appointed hour, but then, a flintlock mechanism is triggered and, with a flash and a bang, a lighted candle swings up from a compartment within, jack-in-a-box style, and illuminates the bedside. In fact, if the candle isn’t securely fixed in its swivelling socket inside the clock, there is a distinct possibility it is projected onto the bed itself, guaranteed to have the occupant up and about.

The mission of the two Advisers included a desire to see – and film – the clock working, if at all possible. Needless to say, careful preparation was required to ensure the clock itself was safe and the test was carried out in a brick-lined vault at the back of the Manor, although only a tiny quantity of black powder is needed to fuel the flintlock.

In the event however, not a single ignition took place, as the flintlock’s frizzen (the hardened steel plate against which the flint is supposed to strike the sparks) appeared to be too worn already, and would not oblige. It seems the clock has done its fair share of early morning duties over the years and is entitled to take an extended rest.

A few more experiments will take place to see if we can’t persuade it to perform just once more for the cameras; meanwhile further research on the clock, on Mornier, and on other examples of this kind, is underway and will be written up in Antiquarian Horology in due course.

The Clockmakers’ Charter

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

The Queen’s Jubilee this year is being celebrated at Royal Museums Greenwich with a terrific new exhibition, 'Royal River', which takes a fascinating and richly illustrated look at the royal history of the Thames. The city livery companies naturally play a central role in the story, and the curator, David Starkey, wanted to display a good example of an original royal charter from one of the companies.

The finest surviving of all the original royal charters just happens to be that of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, the charter of incorporation granted by King Charles I in 1631. The document itself was completed in 1634, Mr John Chappell being paid £4 for its 'flourishing and finishing'.

For the first time I have had the chance to look at it closely and have been reflecting on its significance.

It is in extraordinarily well-preserved condition and is a most beautiful and evocative thing. The obvious beauty of the document lies in its illumination and the elegant script, so carefully delineated on the vellum. But there is a second, less obvious, beauty within the charter, and one which I, as an historian and member of the company, personally find inspiring and reassuring.

Unlike many of the livery companies, which today have little practical connection to their founding craft, and have had many changes to their charter reflecting this, the Clockmakers Company still regulates its activities with reference to its 380 year old charter, which is still a relevant and legal constitution.

So carefully and intelligently worded was the charter that those parts which have become obsolete (such as the right of the Company’s officers to destroy poor quality work of a member) were always optional and can simply be allowed to pass unnoticed, but those parts relating to the administration of the company and its membership were obligatory, yet are as relevant today as they were then.

Today the majority of members of the Company’s governing body, The Court, are real horologists, and we can proudly say this is one company which has not lost connection with its roots.

Our pristine charter connects us straight back to our horological forefathers and it’s wonderful to reflect that today’s members of the Clockmakers Company are the natural and direct successors of Edward East, Thomas Tompion, Joseph Knibb and all the great names from the Golden Age of English clockmaking.

A book sale to remember

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

Many of us who are captivated by the history of timekeeping have an equal interest in the historical literature on the subject; in fact, such is the fascination with antiquarian horology, that quite a few of us have more books than clocks and watches!

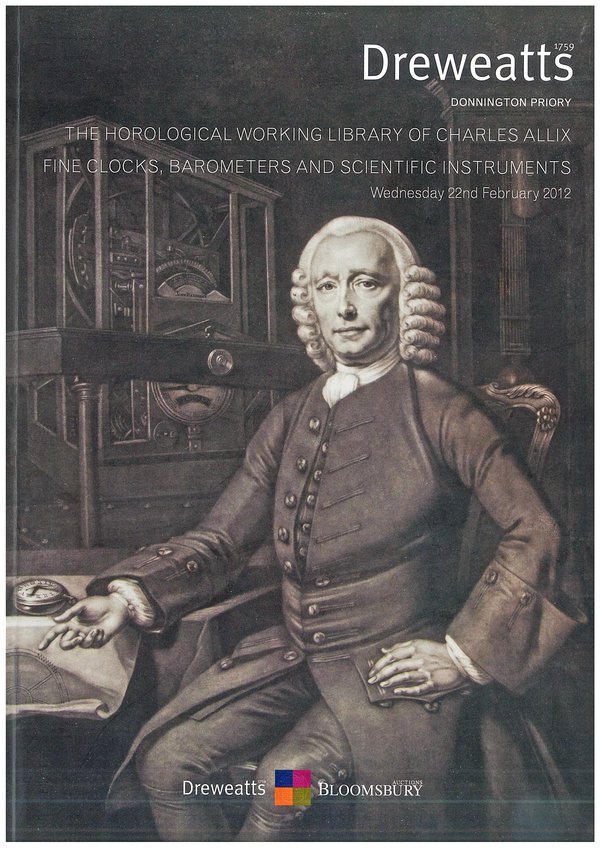

For these horological bibliophiles (don’t try saying that with your mouth full!), ‘the sale of the century’ took place last month (on 22nd February) when Dreweatts of Donnington sold the working library of the distinguished antiquarian horologist, Charles Allix.

Charles, who is now enjoying a well-earned retirement, amassed a very fine collection of books and ephemera, and with subjects ranging from turret clocks to watches, there was something for everyone.

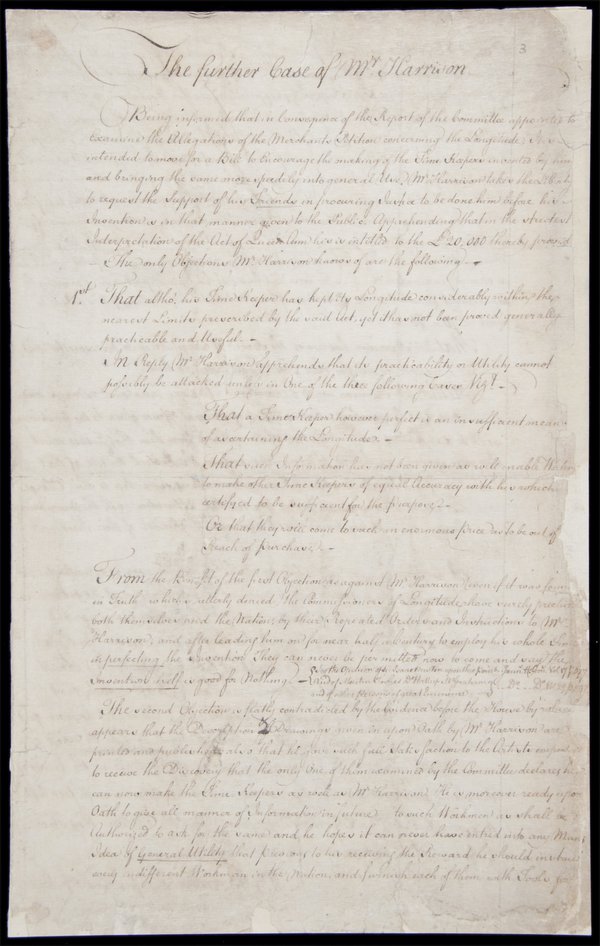

Undoubtedly the stars of the show were a small group of manuscripts which had belonged to the great John Harrison (1693-1776) and it was predictably these lots which brought the highest bids.

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers hold the largest body of original Harrison manuscript material, and the Company were keen to add these, which were some of the very last Harrison-related documents out of safe captivity in museum collections.

The lots were hotly contested – some of the prices were a long way above upper estimates – and the horological world was reminded again of the enduring interest and importance of the Harrison story.

In the event, most were acquired by the Company (Charles Frodsham’s kindly doing the bidding on their behalf), and they are now safely secured for the future and available for research.

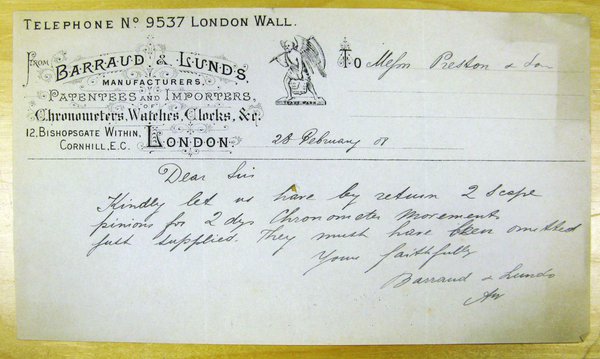

My own organisation, recently re-named Royal Museums Greenwich (after the Borough was granted Royal status) was also successful in acquiring some fascinating correspondence from the firm of Preston’s of Prescot, one of the most significant English manufacturers of rough movements for marine chronometers.

The extraordinary detail informing the day-to-day processes involved in making and supplying these movements to the finishing trade, will greatly enhance the research currently being carried out on the museum’s collection of marine chronometers.

This research is due to be published in a large and definitive catalogue The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich , due out in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the 300th anniversary of the famous Act of Parliament offering huge prizes for solutions to the problem of finding longitude at sea.

Horological research

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

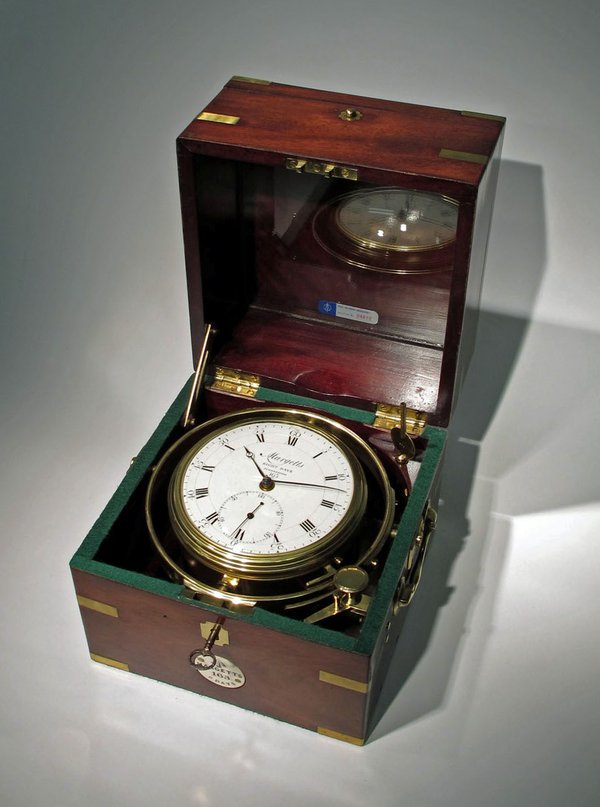

Determined to ‘practice what we preach’, a number of us on the Council are currently involved in our own horological research; my project at the Royal Observatory Greenwich is the study of our enormous collection of marine chronometers.

The research will lead to the publication of a catalogue raisonne, ‘The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich’ in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the tercentenary of the passing of the great Longitude Act in 1714, and will form one of the series of Greenwich instruments catalogues published in recent years in conjunction with Oxford University Press.

All the timekeepers by the great John Harrison have now been fully dismantled, studied, photographed and researched (and put back together!) and I am now slowly working my way through the rest of the collection, from early examples by John Arnold up to the 4 orbit Hamilton, the rare Model 21 marine chronometer adapted to aid pacific navigation.

One of the great challenges for the catalogue is to write a ‘spotters guide’ to help collectors, dealers and curators with the tricky question of ‘how to date and evaluate your marine chronometer’. In the early years there were obvious differences in evolution and from one maker to the next, but, from the 1840s, marine chronometers appear, at first glance, to change very little through into the 20th century.

There are however many things to look out for, both in the movement and the box, which will enable a more sophisticated evaluation of a given chronometer. But be warned! These functional objects have often had considerable alteration and ‘upgrades’ over the years (lives depended on their being ‘up to date’, after all) and we should be prepared to accept, and dare one say rejoice in, instruments with a complex history. Later posts may expand on this interesting aspect.