The AHS Blog

Stinky horology

This post was written by Tabea Rude

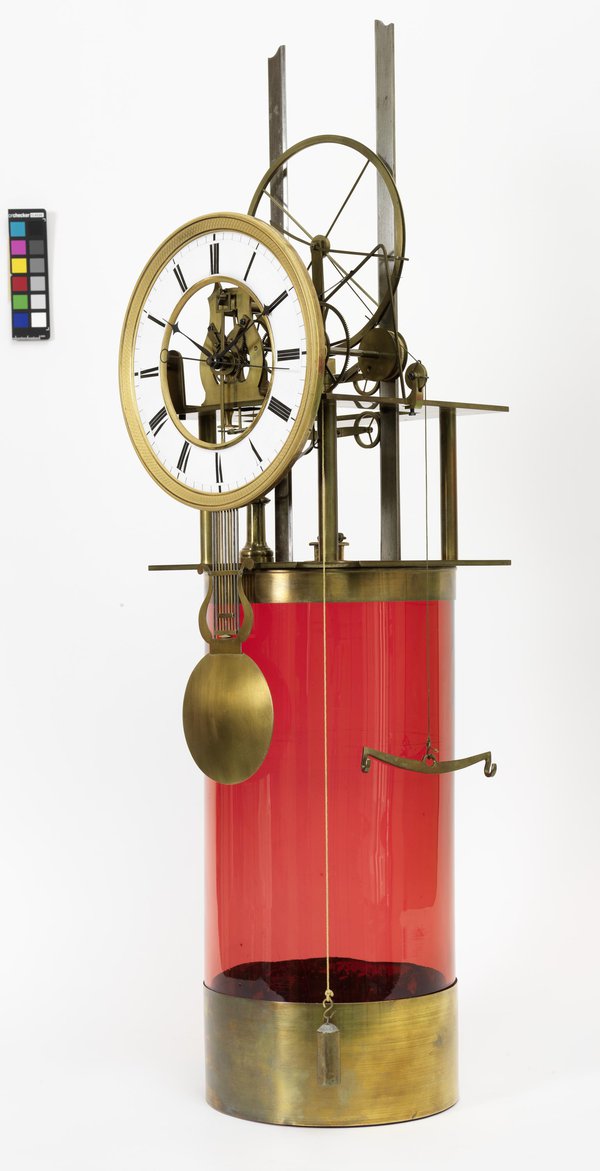

Not many clocks can claim a major olfactory experience by nature of their operation, but this one must have done: the hydrogen clock by Pasquale Anderwalt (1806-1881).

It is mentioned from the early 1840s onwards in several German publications. Anderwalt was a mechanical engineer and worked in Trieste. He developed machines for agricultural use and received a privilege for improvements on windmills. In the 1850s, he was involved in finding and proposing solutions for the frequent shortages of drinking water in Trieste.

For that reason, he was sent to the 1851 World Exhibition in London, to find out what the department of hydraulics and the gathered experts from all over the world had to offer. He also brought his hydrogen clock for presentation. Quite a number of these curious hydrogen clocks survived. Some readers may have seen one of these on display in the Clockmakers Company Collection at theScience Museum. Another is found in the Vienna Clock Museum, with three further examples in museum storage in Vienna and Trieste.

All of them have this rough idea in common: The glass cylinder is filled with sulphuric acid, the owner adds zinc and closes the lid. The zinc then reacts with the sulphuric acid to hydrogen, pushing a piston upwards, which in turn rewinds the weight.

Anderwalt himself claims that 'one ounce of zinc will last the clock machine at least for a human life span'. Probably a very trendy machine in its time, it could definitely compete with other alternative power ideas and not-so-perpetual-motion-clocks. Articles about these have been published in a number of Austrian, Moravian, Italian as well as Bavarian newspapers and scientific reviews. It is not known how many of these objects exploded during use or how smelly they really were.

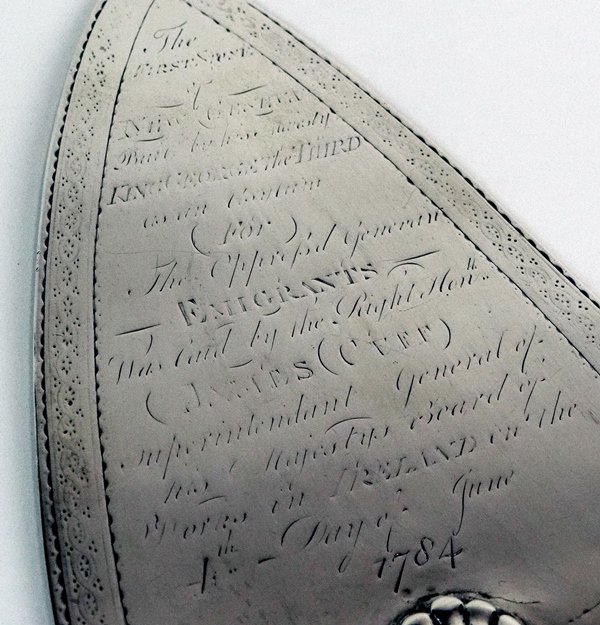

Ó Shin 1784

This post was written by Bryan Leech

Imagine a watch of exquisite artisanship with the finest finishing on the bridges, mostly Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua. Underneath, a family name clearly of Swiss extraction, and the phrase, in Irish: Ó Shin 1784 ('since 1784').

IPA pronunciation for ó shin is: oː ˈhɪnʲ

This is the story of how Ireland might have become a leading producer of luxury timepieces.

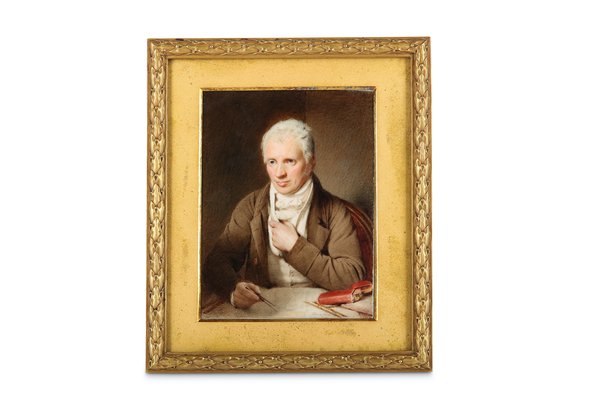

British-born architect James Gandon (1743–1823) worked on many prestigious projects throughout Ireland. However, little is known of his designs for New Geneva, a university town to be built at Passage East, County Waterford, S.E. Ireland, for refugees from the Geneva Revolution of 1782.

In the late 1780s Geneva was in turmoil. A conservative aristocracy of 1,500 or so burghers formed the pool from which all city officials were drawn.

A prosperous and ambitious middle class of Genevan ‘citoyens’ (citizens) – artisans and craftspeople in watchmaking, weaving and printing – were excluded from the franchise, along with a larger number of ‘habitants’ who had fled religious persecution in France. All were profoundly affected by the liberal ideas of the time and wanted democratic rights in line with their aristocratic counterparts.

Tensions mounted, and, in 1782, these disquiets concluded in a small and bloodless revolution. The council was overthrown and its officials jailed. However, to the despair of the democrats, the council was restored to power by the armies of France, Savoy, and the Canton of Berne.

Their only hope seemed to be to emigrate and establish colonies elsewhere. Valued for their knowledge and skills, invitations arrived from The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, from England, and Ireland.

Fearing competition from established English watchmakers, the Genevans plumped for Ireland, where increased powers to self-rule granted by the British Parliament had led to a wave of elaborate plans for economic and cultural development. The formation of a 'colony' for the Genevan artisans was seen as a way to stimulate Irish trade.

The project had the backing of the Viceroy, Lord Temple, and a grant of £50,000, equivalent to approximately £10 million today. This money, and 11,000 acres, were pledged for the establishment of the colony in the Gandon-designed town, named New Geneva.

Gandon’s plans were said to have many similarities with the French city of Richelieu. They included three churches and splendid crescent. An academy for arts and science was to overlook an open square to the south and the town market featured its own square in the south-west corner. The town hall was to be to the north and a hospital in the north-west corner of the town.

In July 1784 construction began. Meantime, however, the Genevan artisans had become more tolerant of the reformed Geneva Council and the thought of starting anew in a foreign country less promising than it had two years earlier. By late 1784 Gandon's project and building work were abandoned.

Today, the only remains of New Geneva are some ruined walls in a grassy field. Fortunately for the original Geneva, the watchmakers remained in their native city. And Stríoca de Ghiniúna Nua (Côtes de Nouvelle Genève) never became that sought-after embellishment for modern day watch aficionados.

The No.4

This post was written by Jonny Flower

It’s really not every day that a dealer in horological objects gets to make a once-in-a-lifetime report. But, to the door of number 4 Lovat Lane, London, residence of the AHS, to convey news of a handsome discovery! Buried under decades of dust in a darkened room it has been found! Behold…the Synchronome No. 4, which came to me as part of the estate of an electrical engineer.

In photos it looked like it might be a self constructed version, especially with the blue Hammerite paint on the frame. Upon seeing it however, it was obvious that it was factory built.

It was smaller and more delicate than usual Synchronomes and the carvings in the upper door frame were sunrise style, not floral. A very early Hit and Miss synchroniser shows that at some stage it was connected to another Master clock, possibly a Shortt tank.

Once the synchroniser had been removed the bronzed NRA plate engraved with the magical No.4 appeared, one of the very first production Synchronome one-second master clocks.

No pilot dial was evident. The movement had separate footed cocks for the count wheel, latch and the gravity arm. The coils were attached to an L-shaped projection from the main frame casting. The pendulum has a typical steel trunion with adjustable brass sleeve, delicate brass weight tray and a nicely made lead filled bob with small brass shaped rating nut. The impulse pallet was of a shape I had not seen before with stepped sleeve, lipped tip and a separate screwed on support plate for the gathering wire and jewel.

The mahogany case was a design that was used for the early prototype clocks with brass frames and used before the adoption and incorporation of pilot dials.

After all these discoveries I consulted friends and colleagues together with all the books and literature to establish where No.4 sat in the time line of Synchronome production. What came to light was that there was a fundamental change in the construction of the one-second master clocks very early on in their production. In Bob Miles’ excellent book on Synchronome he had noticed this too.

This first series of numbered production models I am going to call the Interim Series. The Interim Series of one-second master clocks can be distinguished as follows:

Frame: We know from physical evidence that from serial number 4 up to and including number 41 the cast iron frame had an L-shaped protrusion to support the coils and armature pivot plate.

Movement: Footed brass cocks are used for the Count wheel and gravity arm. The latch used until 1920 is positioned on an adjustable brass frame that is screwed to the back plate.

The back stop is a jewel with a coiled spring-like counterweight that pivots through a pillar attached to the inside of count wheel cock.

No.4 has a case that was used for the brass movement prototypes with a narrow trunk, pediment top and sunrise carvings in the upper door frame. Uniquely at this point in time it is the only one with a door that has the hinges located on the left hand side. No.41 Has a flat topped case with glazed sides. I believe that this Interim Series was a very small production run of approximately 50 pieces with smaller cases and no pilot dials.

My thanks go to John Fothergill and James Kelly for their help, and of course to the late Bob Miles. I am pleased to report that No. 4 will soon be joining the collection of The Clockworks museum in South London.