The AHS Blog

The last piece of the jigsaw: a relatable story for researchers

This post was written by Su Fulwood

Research is, of course, interwoven through my work. One long-term project is about women and their roles in horology. This started when I was working with watchmaker Geoff Allnutt in his shop and workshops at 8 West Street, Midhurst. Geoff challenged me to go through lists of watch and clockmakers to note down all the women mentioned. After finding hundreds of women among the men, one name stood out: 'Mary Ann Lawrence, West Street, Midhurst'.

A quest began in earnest to find out where in the street Mary Ann had worked.

Years have passed and our research has covered many individual women, including, gradually, lots about Mary Ann. We discovered that she was actually from a well-known family of local watchmakers, the Wrapsons. We found that she took over her brother's premises in West Street following his death. We also discovered that she was close friends with fellow watchmaker, Joseph Charles Ketterer.

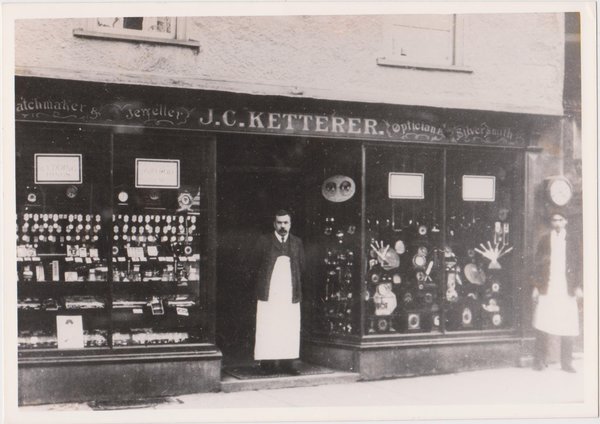

Ketterer, we knew with certainty, had run his business until 1914 from the premises Geoff now occupies.

We couldn’t say, however, whether Ketterer took over from Mary Ann or whether she had worked from another shop. It wasn’t uncommon in Midhurst for there to be two watchmakers in the same street at a similar time.

We did know Mary Ann retired around 1895, and that Ketterer was the executor of her will when she died. We just didn't have that last all-important piece that would tell us if she was part of the history of 8 West Street. It was frustrating.

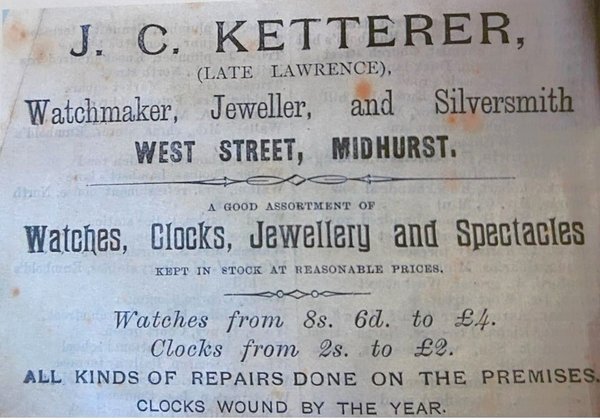

Until now that is ... seven years later, when a chance conversation revealed the existence of a different advert for Joseph Charles Ketterer’s business.

When we saw it we couldn’t believe our eyes. There at the top, unexpectedly, was exactly the information we had been looking for. The words 'J. C. Ketterer (Late Lawrence)' were pure gold for us. It meant that Mary Ann Lawrence (who describes herself as 'Mistress Watchmaker' in the 1881 Census) was running her watchmaking business from the shop before Ketterer. This also meant that the same premises had belonged to her brother Charles Wrapson and, before him, their mother, Mary Wrapson.

Our research began by looking at watchmaking women across the country. But it has become very personal, as finally we were able to show that two of those women inhabited the exact spaces we work from today.

In the meantime, along with my research about women and horology, I get to work with other women today, as more are attracted back to watch and clockmaking.

The tools are important too

This post was written by Seth Kennedy

Many horological workshops contain old tools. It seems to go with the territory. There is something about using a hand tool that has already been around for a century or more. It brings questions, wondering whose hands have previously worked with this object over several generations and what timepieces were they working on?

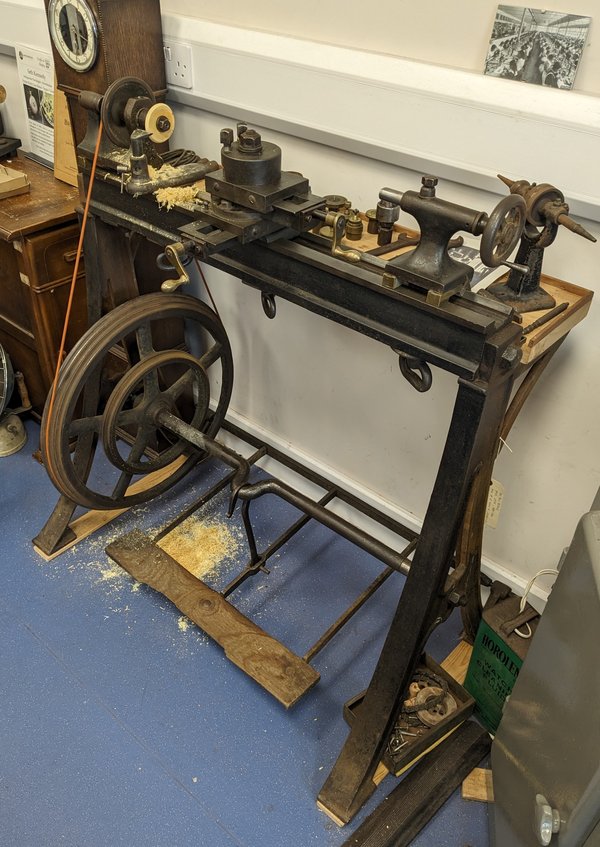

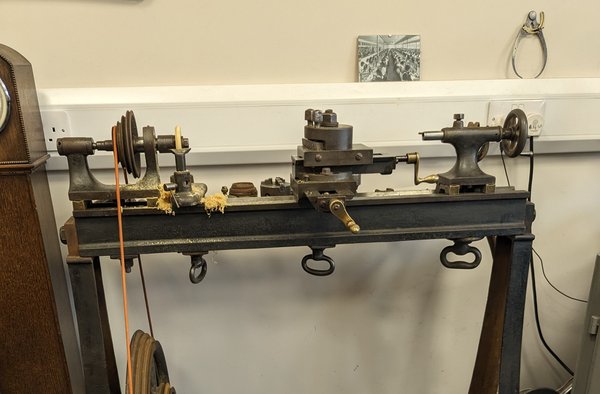

With thanks to a fellow restorer, I recently became custodian of something a bit larger than a saw or a file. It’s a plain lathe by Pfiel most likely made in the late 19th century. Pfiel & Co were tool makers and retailers with a large shop and warehouse on St John Street in Clerkenwell. There are a few details about these lathes that make them distinguishable and so it is possible they were actually cast and machined in London to Pfiel specifications.

The centre height of the spindle is 3.5”, or at least it was, since on this example some home-made brass spacers have been added under the head and tailstock so that larger parts could be turned. These spacers fit the flat front and veed back surfaces of the lathe bed.

The treadle board itself is an incredible survivor, showing its wear of a century of use. Also remaining, though unusable, is a very old gut line that was previously used to connect flywheel to spindle.

What makes this lathe particularly special is that its history is known. It came from the workshop of Daniel Parkes, a fourth generation clockmaker/restorer who was active in Clerkenwell until retirement in 1989. He was a founder member of the AHS and some of his tools are on display in the museum of The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. Parkes used only traditional equipment and methods in the restoration of fine English clocks of the 17th and 18th century golden age.

The lathe could have come from his family’s workshop on Spencer Street, which was destroyed by a V1 bomb in June 1944 but from which he salvaged some equipment. Or it might have already been in the workshops that Parkes then moved to on Brisset Street, where a partnership was formed with A. & H. Rowley, also a firm with long Clerkenwell roots.

Either way, someone in one of those businesses needed a lathe in around 1890 and so walked down the road to the Pfiel shop and bought this one. After Parkes’s retirement it went to Mike McCoy, then to Matthew Hopkinson and then recently to my workshop.

It has now had some cleaning, oiling, a hidden strengthening plate added to the treadle, a new leather belt fitted and a new shelf added as the original had gone missing.

Tools are meant to be used and so, after perhaps 30 years of slumber it will now occasionally be put into action again, for turning boxwood chucks used in watch case making and other light tasks.