The AHS Blog

Dead on 12 o'clock

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

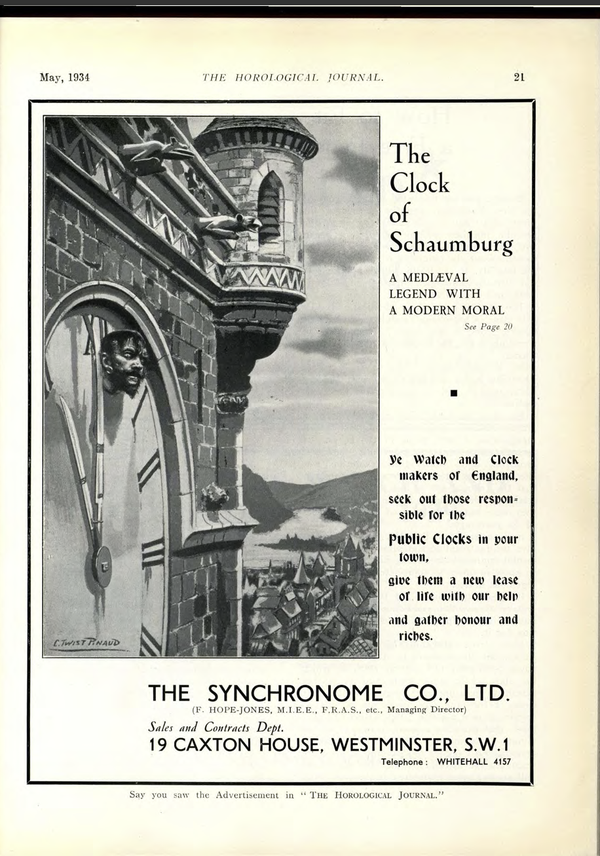

Frank Hope-Jones must have had a taste for the gothic. In 1934, his Synchronome Company advertised the new ‘Synchronomains’ turret clock unit citing a ‘medieval legend with a modern moral’.

The ‘legend’ went that during the Peasants’ War of 1524–5, the rebel Goerz of the Iron Hand was taken hostage at Schaumburg Castle, where his enemies had made implausibly macabre preparations for his torture and execution. Dragged to the summit of the clock tower, Goerz’s head was thrust through the enormous dial just below the 12.

The great hands had been reversed – the minute now the shorter of the two – and replaced with blades. At every pass, the reduced minute hand would pierce the victim’s flesh, until the newly extended hour reached the twelve, when his head would be severed from his body and fall into the moat.

However, the Synchronome Company was sceptical any weight-driven turret clock could muster the requisite force for the coup de grace. If only it had been a Synchronomains! In that case, 'either hand would have completed the headsman’s task with ease – without interfering with the accuracy of the clock!'

The story was pitched as a medieval legend, but someone at Synchronome must have been reading The Royal Magazine, a cheap monthly run by C. Arthur Pearson. 'The Clock Face of Schaumburg', by Kirby Draycott, appeared in its inaugural issue (November 1898). The frontispiece showing Goerz’s final moments – later snaffled by Synchronome – was by the English artist C. Twist Pinaud, who seems to have taken some liberties with the clockless Schaumburg Castle.

However, Draycott’s protagonist was real enough: the historical Götz von Berlichingen (1480–1562) was a mercenary soldier whose titular prosthetic limb can still be seen at Jagsthausen Castle.

His end was less bloody but arguably equally unlikely – he died peacefully in his 80s. Perhaps Draycott thought death by turret clock an ironically fitting alternative end for 'the iron hand'.

At any rate, the purportedly medieval story certainly furnished an attention-grabbing campaign for the Synchronomains, which promised clocks unfailingly dead on the hour.

The conservation of precision horology

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A few weeks ago I attended a fascinating international three-day conference on the conservation of historic regulators and chronometers, hosted by the curatorial and conservation staff at Palermo Observatory in Sicily, part of the INAF group (Instituto Nationale di Astrofisica) of Italian observatories, all of which have historic collections of instruments and timekeepers.

The lectures, which were presented by specialist curators and conservators from Italy, UK, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, covered a great range of horological subjects from philosophical preservation, practical conservation of collections and a more general discussion of the care and preservation of these especially vulnerable objects.

Although the various papers reflected quite different perspectives, all the speakers found common ground on the principles of care and spoke with one voice on the aims of their roles as custodians of our historic collections.

A particular aim of the conference, discussed in depth in the final group meeting, was to formulate a common set of guidelines for future curators and conservators, and an internet forum was then established to continue the dialogue in future.

The hosts at Palermo Observatory, Ileana Chinnici and Maria Carotenuto, to whom we were especially grateful for organising the event, were particularly keen to seek advice from delegates on formulating a programme of care for the fine collections at Palermo. This might then apply to all the historic precision instruments in the Italian observatories under INAF.

We learned some fascinating statistics:

-- these instruments represent 80 per cent of the astronomical heritage in Italy, and 10 per cent of these objects are timekeepers of one kind or another;

-- in all the various observatory collections there are 53 clocks, 31 chronographs and 12 box chronometers;

-- 25 per cent of the horological material is of British manufacture, 20 per cent is Swiss, 13 per cent is Austrian/German, 7 per cent is French, and 35 per cent is Italian.

Naturally the regulators at Palermo formed the focus of much interest and discussion during the conference, and what fine things they are! The stellar list of makers includes Mudge & Dutton, Janvier, Vulliamy, Cumming & Grant, Frodsham, Dent and Riefler.

Palermo Observatory had been founded in 1790 with Guiseppe Piazzi as its first astronomer. It was Piazzi who, on a visit to London and Paris in the late 1780s, commissioned the regulators from Mudge & Dutton, Cumming & Grant and Janvier as the first timekeepers for astronomical use at Palermo.

Having recently studied and written about the works of Alexander Cumming (Antiquarian Horology, March 2022), I found the example by Cumming & Grant, which has Cumming's own form of gravity escapement, of particular interest. It is very similar to the regulator signed by Grant only, in the Clockmakers' Company Museum in the Science Museum, London, both clocks being of superb quality.

A really interesting and valuable three days; there will hopefully be a chance to return soon to study this fine collection more closely.

The various rooms in the historic building now form the museum of the observatory, which can be visited in person or virtually.