The AHS Blog

We the accumulators and the responsibilities

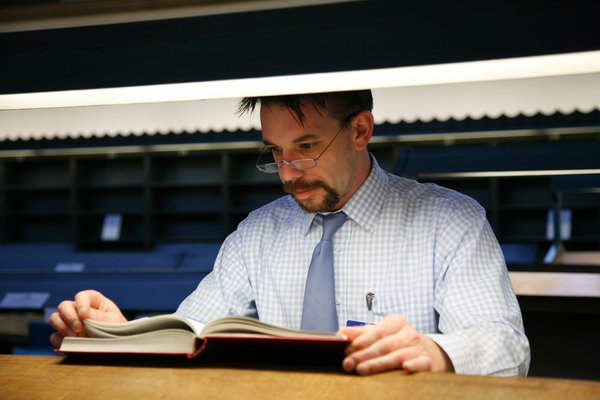

This post was written by Andrew King

Many of us spend an endless number of hours researching the story of timekeeping from various scientific and historical points of view as well as studying the lives of the makers of clocks and watches through the same wide spectrum.

There is a challenge and excitement in research as we trawl through libraries and record offices, scan the internet and trace living descendents who, surprisingly even after a period of possibly many decades or even centuries, can still turn up documents or even artefacts of significant historical importance.

All this leads us to as close an understanding of times past as we are ever going to be able to achieve. Although we can never really fully understand what life could have been like in previous times, with a certain diligence in trudging through archives we can begin to gain a sense of life as well as a tangible sniff from the stench of the streets.

In historical research it is as important to have an open mind as it is to have a persistent and untiring curiosity that questions every fact and figure until a reasoned acceptance can be reached. Although a quest for new sources of information is of paramount importance, it is equally necessary to read and read again all the established works as well as more recent studies which although maybe only allied to our core interest, may nonetheless be able to add a reflection if not some new knowledge.

Over a period of years there will be an accumulation of research – in short, an archive. It is at this point that the real work starts because those years of research now need to be sifted into a ground plan for publication.

Without writing and publishing as much as a lifetime’s work can be thrown away. The published work may be anything from a paper offered to our Journal to a mighty tome. Everything is of potential importance and everything can be considered as a contribution to our history of time.

The dissemination of knowledge is the heart beat of history that opens up the past to contribute to the world we live in today to enable us to project our thoughts into the future.

Oral history in electrical timekeeping

This post was written by James Nye

In the electrical timekeeping world, whilst things kicked off in the mid-nineteenth century, there was considerable development all the way through the twentieth century, with the distribution of time becoming commonplace, and various technologies emerging to replace others over time.

There are many people alive who have worked at the heart of those emerging technologies – or witnessed their emergence – technologies such as atomic timekeeping, or the use of quartz as an oscillator, starting in research labs and ending up on countless millions of wrists.

At the first of the AHS London Lecture Series meetings at the Royal Astonomical Society in January, I was delighted to announce the launch of a project we are sponsoring in the Electrical Group – to promote the recording of oral history. Witness programs exist in many fields and prove an invaluable way of recovering and recording the fascinating and highly personal insights of people who can genuinely say 'I was there.'

Lucas Elkin, of Cambridge University Library, has kindly offered to take the lead with this project, targeting individuals with the specialist and personal knowledge we want to tap, by way of a recorded (and relaxed) interview.

One of his first subjects will be Bob Miles, who spent his career working on the early development of quartz technology. We look forward to being able to point people to the transcribed records of these fascinating conversations.

We have a list of about a dozen candidates already identified, but if the trial is successful we shall be looking for more. If you any ideas, or want to get involved, please get in touch!

Time by wireless

This post was written by David Rooney

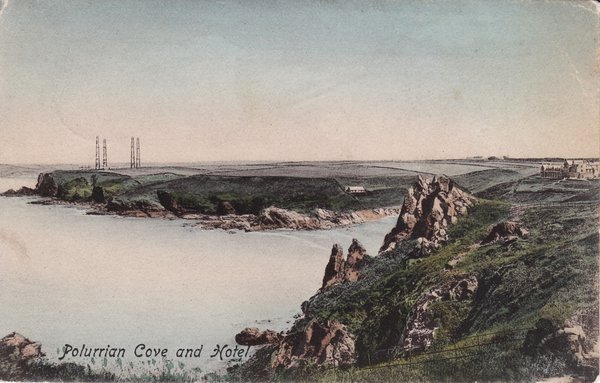

The current header picture at the top of our blog is from an Edwardian postcard entitled ‘Polurrian Cove and Hotel’. Here’s the full version.

I love historic scenes like this which show modern technology set within seemingly timeless surroundings. Here, Marconi’s Poldhu wireless station looms in the background of a picturesque little bay in Cornwall.

This was the transmitter for the world’s first transatlantic radio message, received in Newfoundland, Canada, in December 1901.

One of the earliest uses of wireless communication was radio time signals. Experiments began in America in about 1904, with time signals from Paris’s Eiffel Tower being broadcast from 1909. Soon, standardised international codes were established, giving a much-needed boost to ships and many others who needed accurate time checks around the world.

Today, radio time signals are still very much with us. The BBC’s six-pips signal, inaugurated in 1924, is still accurate to a fraction of a second – as long as you’re listening on analogue. Coded time signals are sent out by the National Physical Laboratory from a transmitter in Cumbria, a system that began in 1927. And even the latest satellite navigation systems operate on super-precise radio time signals.

William Mitchell’s 1923 book, Time & Weather by Wireless, is a terrific read or, if you can’t get hold of a copy, I talk about the history of radio time in my 2008 book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady. And if you want to get more deeply involved, you might consider joining the AHS and its electrical timekeeping group. It’s full of people who think Edwardian postcards of Cornish transmitter masts are cool.

You do think the postcard’s cool, surely. No? It’s just me? Oh.

Horological research

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

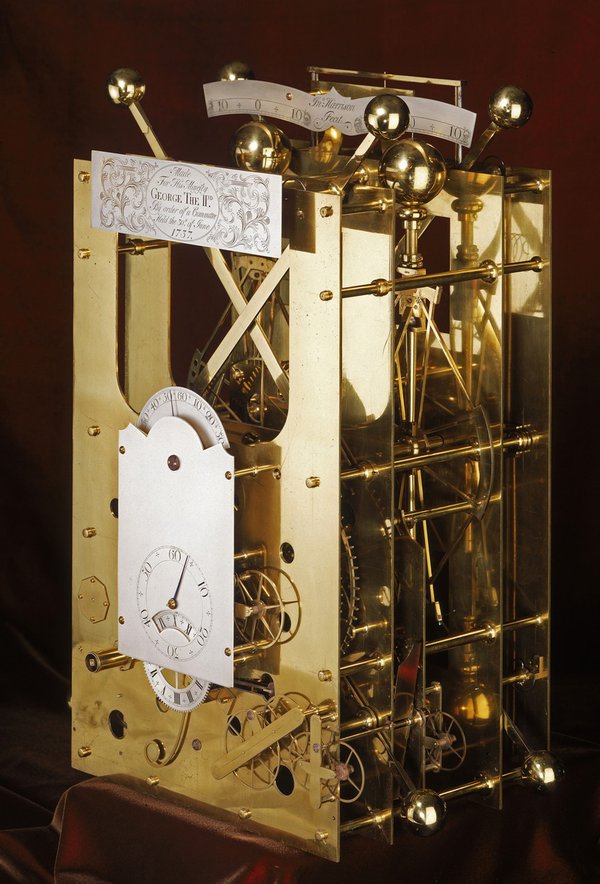

Determined to ‘practice what we preach’, a number of us on the Council are currently involved in our own horological research; my project at the Royal Observatory Greenwich is the study of our enormous collection of marine chronometers.

The research will lead to the publication of a catalogue raisonne, ‘The Marine Chronometers at Greenwich’ in 2014, as part of the celebrations to mark the tercentenary of the passing of the great Longitude Act in 1714, and will form one of the series of Greenwich instruments catalogues published in recent years in conjunction with Oxford University Press.

All the timekeepers by the great John Harrison have now been fully dismantled, studied, photographed and researched (and put back together!) and I am now slowly working my way through the rest of the collection, from early examples by John Arnold up to the 4 orbit Hamilton, the rare Model 21 marine chronometer adapted to aid pacific navigation.

One of the great challenges for the catalogue is to write a ‘spotters guide’ to help collectors, dealers and curators with the tricky question of ‘how to date and evaluate your marine chronometer’. In the early years there were obvious differences in evolution and from one maker to the next, but, from the 1840s, marine chronometers appear, at first glance, to change very little through into the 20th century.

There are however many things to look out for, both in the movement and the box, which will enable a more sophisticated evaluation of a given chronometer. But be warned! These functional objects have often had considerable alteration and ‘upgrades’ over the years (lives depended on their being ‘up to date’, after all) and we should be prepared to accept, and dare one say rejoice in, instruments with a complex history. Later posts may expand on this interesting aspect.