Time by wireless

This post was written by David Rooney

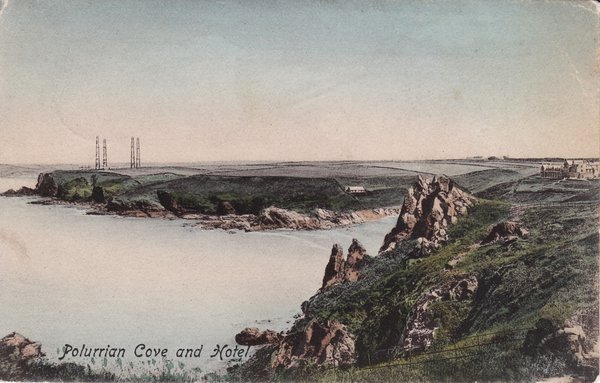

The current header picture at the top of our blog is from an Edwardian postcard entitled ‘Polurrian Cove and Hotel’. Here’s the full version.

I love historic scenes like this which show modern technology set within seemingly timeless surroundings. Here, Marconi’s Poldhu wireless station looms in the background of a picturesque little bay in Cornwall.

This was the transmitter for the world’s first transatlantic radio message, received in Newfoundland, Canada, in December 1901.

One of the earliest uses of wireless communication was radio time signals. Experiments began in America in about 1904, with time signals from Paris’s Eiffel Tower being broadcast from 1909. Soon, standardised international codes were established, giving a much-needed boost to ships and many others who needed accurate time checks around the world.

Today, radio time signals are still very much with us. The BBC’s six-pips signal, inaugurated in 1924, is still accurate to a fraction of a second – as long as you’re listening on analogue. Coded time signals are sent out by the National Physical Laboratory from a transmitter in Cumbria, a system that began in 1927. And even the latest satellite navigation systems operate on super-precise radio time signals.

William Mitchell’s 1923 book, Time & Weather by Wireless, is a terrific read or, if you can’t get hold of a copy, I talk about the history of radio time in my 2008 book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady. And if you want to get more deeply involved, you might consider joining the AHS and its electrical timekeeping group. It’s full of people who think Edwardian postcards of Cornish transmitter masts are cool.

You do think the postcard’s cool, surely. No? It’s just me? Oh.