The AHS Blog

A pointless exercise

This post was written by David Thompson

Sometimes, ideas were way ahead of their time and when they were first thought up they had no application. Subsequently, however, the concept became a popular and widely used one.

Today with frequent and easy air travel, as well as instant communication around the world, the appearance of a world time dial on a watch makes perfect sense and indeed such dials are common. A simple Google search for ‘World Time Watch’ brings up over 2 million references.

What use would such a watch be in the second half of the 18th century.

Imagine a man-about-town in London showing off his latest purchase to his friends and being proud of the fact that he could tell them what time it was on other parts of the globe. When any communication with such places would have taken months at least, you can just hear his friends saying,‘fascinating, but what’s the point – and where is Antiqua anyway?

Nevertheless such watches did exist in the mid-18th century and one example survives to this day in the British Museum Collections.

It is a gold pair-cased watch made by John Neale in London in 1770. It shows the time in London, Mexico, Persia, Antegoa, Russia, Italy, China and other exotic places. It was probably sold as a gimmick, as something out of the ordinary and a curiosity which didn’t need to have a purpose – just a bit of fun for the owner who could say ‘did you know………….?

A eureka moment of recognition

This post was written by James Nye

Sometimes, every once in a while, one’s record-keeping comes up trumps. Rooney and I wrote up the history of the Standard Time Company in Antiquarian Horology back in 2007, and widened our scope in the BJHS.

Since then, very little further factual detail has come to light. Certainly there has been a dearth of newly found objects badged STC – which is a shame. We had hoped our piece would bring to light more clocks and ephemera.

Keith Scobie-Youngs of the Cumbria Clock Company unearthed an unusual tower slave last year, which a couple of us thought might well be from STC, but we lacked any evidence. It is of very distinctive form and bears no signature, or if there is one it is beneath layers of typical clock-tower grime. Despite no obvious identifying marks on the corpse, there was nevertheless buried deep in my memory a faint recollection of something of this form.

I didn’t spring naked from my bath and run around West Norwood, I admit, but I did just have that ‘Eureka’ moment, when I remembered having scanned a document that George Arthur, the authority on all matters related to Lowne clocks and instruments, had shown me, years ago.

In the 1920s, there was a period when Joseph William Molden, an Australian entrepreneur, had built a small electric clock empire, which brought together STC and Lowne for a time.

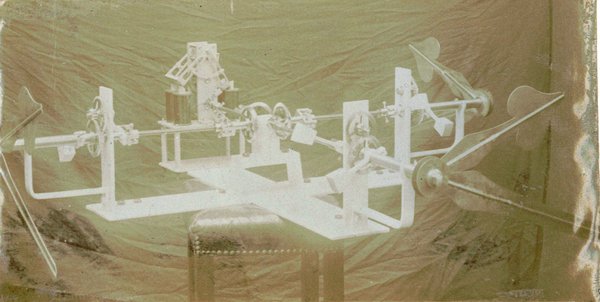

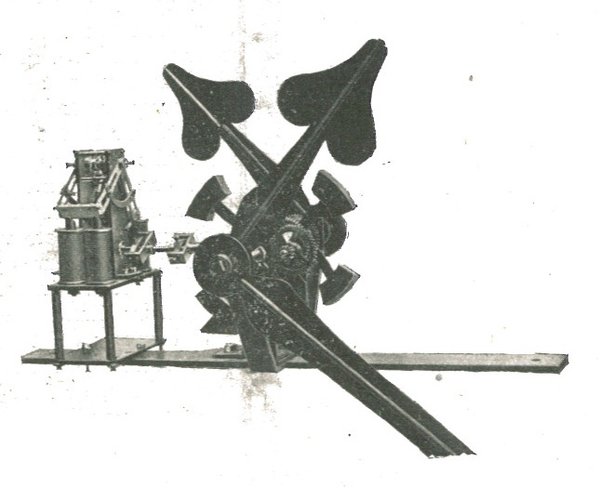

In the Lowne archive there is a picture, very faded, of precisely the device in question, mocked up with leading off work, sitting atop a leather stool. A typewritten description attached to the picture led me to the Horological Journal of 1920, and there, bold as brass, was our movement, titled ‘New Patent Electric Impulse Movement’.

Click here to see the patent. In conclusion, a neat tie-up between original documents and a recovered object. Too bad we still cannot locate one of the master clocks used to drive it, but we live in hope.

Anyone for Venice?

This post was written by James Nye

Rome may be the ‘eternal city’ but for La Serenissima – Venice – time also stands still, or at least it has for me over four decades of visiting the city, with various familiar walks reviving favourite memories at each corner turned.

Something I have noticed for the last thirty years or so is a series of public clocks in the campos and calles – not galley slaves, but alley slaves. These are minute-impulse devices, mostly with a single dial, but a few double-dialled versions on street corners. They have a fairly classic or traditional feel to them, with opalescent dials that are back-lit at night, and cast cherubic and heraldic detailing to the metal cases.

I have never succeeded in tracking down anyone I could ask about their origins or date – if anyone can help, please do let me know. There might be twenty or thirty dotted across the city, and while some are in obvious positions, a few present themselves in seemingly quiet and untravelled quarters, perhaps reflecting changing patterns of street usage.

The cases, dials and hands are survivors of an original installation – on asking among expert friends one commented the pattern is one that could have been used by any one of many different electric clock firms – we would only know which if we could see inside, and I didn’t have a ladder on me this time. No doubt the original central master-clock and city-wide wiring has all long disappeared.

On a visual inspection I would judge each clock now to be independently driven by a local, radio-controlled, electronic master clock, thus giving precise time, corrected automatically for daylight saving. The Venetian authorities have therefore understood (unusually among their peers) that the impulse-clocks themselves can easily be made to last for generations – it is the network that supplies the impulses which may need updating – a message I bang on about frequently, as friends will know.

Venice – a timeless city – moving with the times.

Letters on the dial

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

We are so used to telling the time from dials that we don’t really need the hour numerals. Some dial designs omit them altogether – distinctly uncluttered but also perhaps a bit dull. There is an alternative, which I find more fun.

Watches can be personalized by substituting the letters of the owner’s name for the hour numerals. As Cedric Jagger writes in his book The Artistry of the English Watch , this was by no means uncommon.

If the name did not have exactly twelve letters, the designer had to be inventive, as the three watch photos here demonstrate. The one with JAMES CATLING, dated 1814, gave no problems, but for GEORGE CATLING, dated 1815, NG had to be linked. On the other hand, for the eleven-lettered THO[MA]S STEVENS, dated c. 1840, the designer used a fox’s head at 12 o’clock.

Was this randomly chosen or was the owner perhaps an avid fox hunter?

At least two English churches sport a lettered dial. The one on St Peter’s Church Buckland in the Moor, Dartmoor reads ‘My Dear Mother’, and was commissioned by the man who donated the clock along with three new bells in 1931. And during a recent trip in Norfolk, the AHS Turret Clock Group saw ‘Watch and Pray’ on the dial of the clock at All Saints Church in West Acre.

These are the first words from Matthew 26:41, where Jesus is addressing his disciples on the Mount of Olives just before his crucifixion: ‘Watch and pray, that ye enter not into temptation: the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak’.

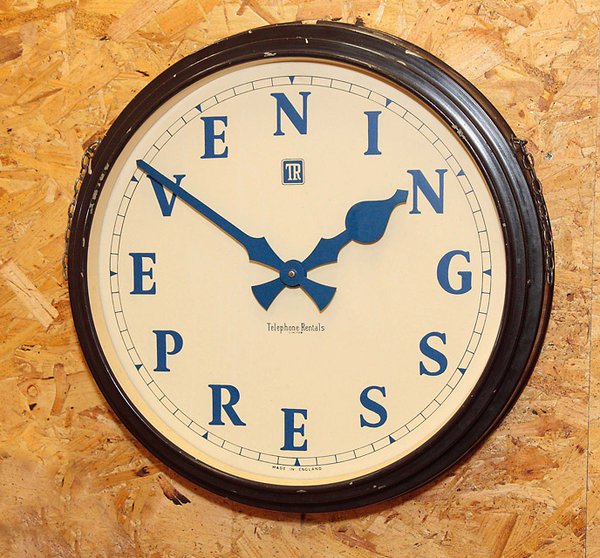

Finally, I was interested recently to come across this image of a mid-20th century electrical wall clock with special dial lettering and hands for the York Evening Press newspaper office, supplied by Telephone Rentals.

If you like this kind of thing, you may want to join a group of enthusiasts who share images and information online on just that: clocks and watches with letters. But on their database I do not see any longcase clocks with letters instead of numerals on the dial. So if you know of one, please leave a comment!

For use of their photos I thank three AHS members: Dave Stables (who published on the Catling watches in Antiquarian Horology of June 2011 and also online), turret clock specialist Chris McKay and the chairman of the AHS Electrical Horology Group, Martin Ridout.

Time by telephone kiosk

This post was written by David Rooney

A few weeks ago I wrote about telephone kiosks. Today I’m returning to that theme, because I’m fascinated by how many clocks are embedded in our daily lives, hidden in the everyday infrastructure surrounding us.

The nights are drawing in. We’ve reset the clocks back to GMT for another year, and many of us start travelling to and from work in the dark. Thanks goodness for street lights – and for the time switches that turn them on and off every day. Countless clocks hidden inside countless lampposts.

But, every so often, hidden technologies reveal themselves, either by accident or design. In 1931, Britain’s watch and clock makers were told about a new way to find the time when out on the street.

'The latest type of Venner Time Switches installed in the G.P.O. telephone kiosks have a glass window over the dial. The purpose is to enable their timekeeping to be more easily checked, but in addition, the device will be useful to the public, for the time to the nearest five minutes can easily be seen.' The Watch and Clock Maker, 15 November 1931.

These time switches were used to operate the kiosk’s lamp, and they were pretty sophisticated.

Each one was a spring-driven mechanical clock, wound up every eight hours by an electric motor. In case the kiosk’s power supply failed, the time switch had enough power in its spring to operate the clock for three days. And every day the switching times were adjusted to track the rising and setting of the sun.

You can find out more from a 1934 article reproduced here. But could the time switches really be ‘easily’ seen, as the quotation states? Here’s a photograph of one of them in situ. I’ll leave you to decide…