The AHS Blog

The basics – how a timekeeper works

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

Old clocks and watches are fascinating even without knowing how they work, but just a simple explanation provides a much deeper appreciation.

The timekeeping function of mechanical timekeepers can be explained as just five elements:

1 – Energy Source

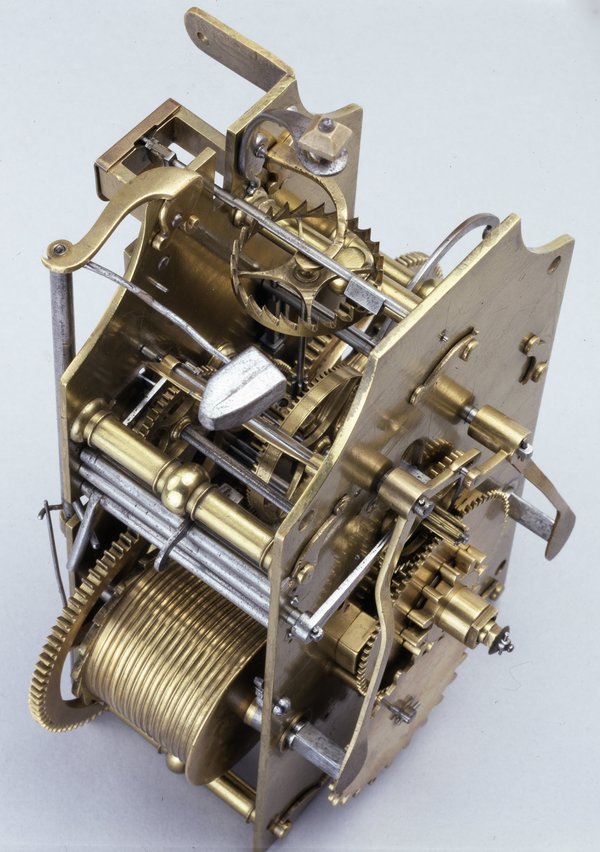

All machines, including timekeepers, need energy to work. The energy is usually stored in a weight or spring. When it is wound, energy is transferred from our muscles and into the driving weight (as it moves up against the force of gravity) or the mainspring (as it tightens-up). This energy is released into the timekeeper as the weight drops or the mainspring unwinds.

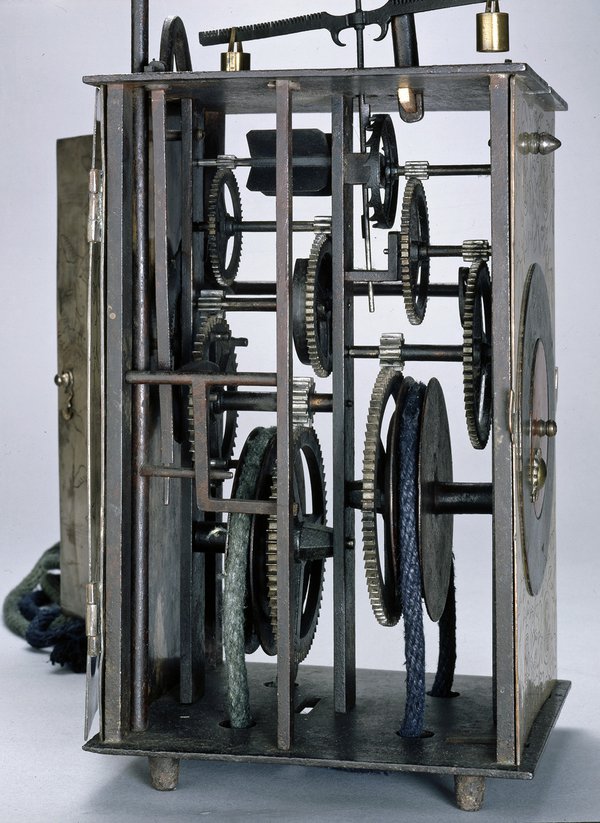

2 – Wheels

An interconnected series of toothed wheels and pinions, known as a train, transmits the energy through the timekeeper. The energy source moves slowly and the wheel at the furthest end of the train moves quickly. This is the opposite of a car gearbox, where the engine revs quickly and the wheels on the road rotate more slowly.

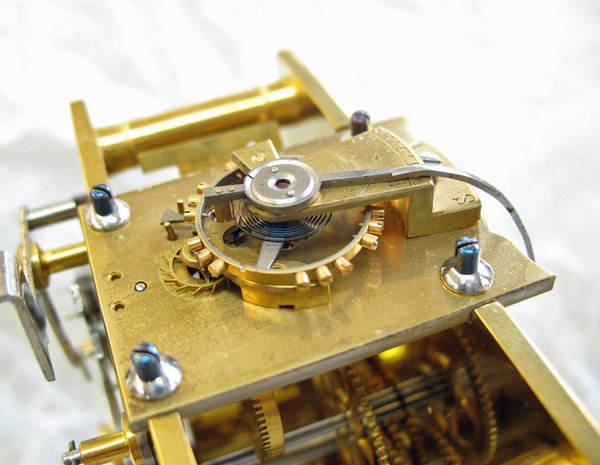

3 – Escapement

The escapement is connected to the quickly moving end of the train of wheels. Like a turnstile which allows one spectator through at a time, the escapement allows one wheel tooth to pass through (or 'escape') at a time. Without it, the wheels would whizz until the weight hit the floor. The ticking of a timekeeper is the sound of the escapement stopping a wheel tooth.

4 – Controller

The controller is connected to the escapement – it controls the rate at which it allows the teeth to pass through. As each tooth passes the escapement, it gives the controller a little push to keep it going. A common controller is a pendulum, which is just a hanging weight – give it a push and gravity makes it swing, at a steady rate. Because gravity is very constant, pendulums are great for good timekeeping.

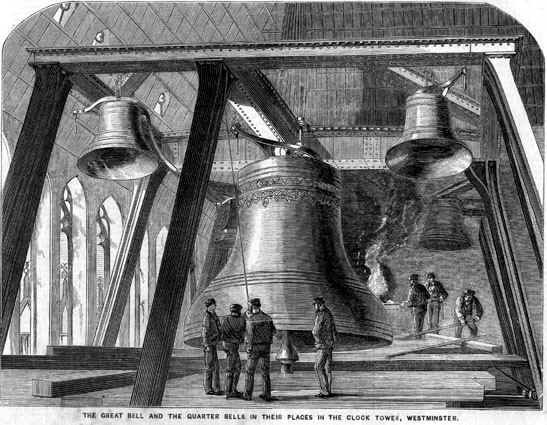

5 – Indicator

The part of the timepkeeper that tells us the time. Most familiar are hands on a dial. A clock striking a bell gives an aural indication of time – sometimes from many miles away.

These five elements apply to (almost!) all mechanical timekeepers from the most ancient to the modern. They can vary wildly, but are there if you look!

PS This superb website has interactive animations showing how escapements (and some other horological bits) work.

King’s Cross – March 1952

This post was written by James Nye

I am spending every waking minute at present researching and writing about Smiths, owner of the English Clock Systems marque (ECS). Just now I came across an article about ECS in the March 1952 in-house Smiths magazine, and thought it worth sharing some of the accompanying images.

Based on surviving clocks, ECS is perhaps now best known for: a range of master and slave clocks, similar in concept to the Synchronome; synchronous public clocks; and process timers (e.g. darkroom clocks), which often turn up on eBay.

I don’t think any pictures of the inside of the original ECS works on Wharfdale Road, King’s Cross, have been published in a long time, so here we go, with a small selection.

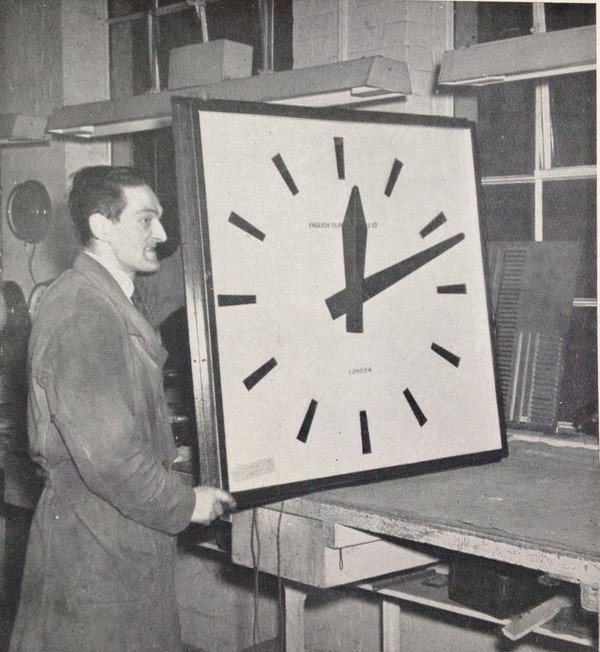

The first shows Reg Boskett, showing off a modern clock dial for exterior use. In the next shot, Dolly Etheridge is shown operating a capstan lathe – Dolly joined the firm in 1942, and was also a competition dancer!

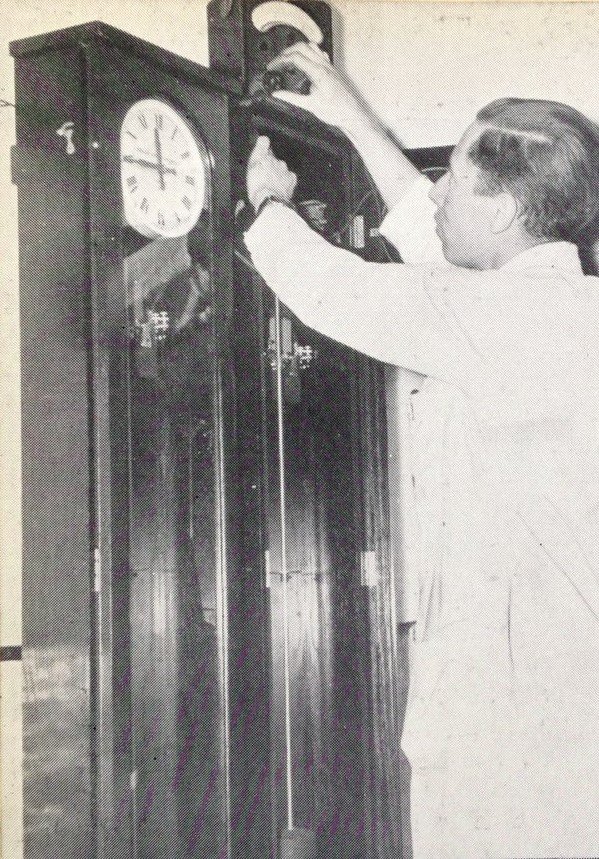

The firm’s original business focused on importing and installing Ericsson time recorders, but little is reported of the time recorders manufactured in fairly large numbers by ECS all the way through to the 1970s. Another shot shows Jimmy James, an old-timer from the firm’s beginnings, in the time recorder department, with an array of movements.

The final shot shows the most sought-after object, the ECS master clock, in the main assembly shop, with Jack Horsfall, foreman, using his Avometer to set-up the series resistance.

At the time all these pictures were taken, the firm still had a successful future ahead of it, but in less than thirty years its market was eroded, and it was absorbed by Blick in 1980.

Martin Ridout, webmaster for the AHS, is also our resident expert on the English Clock Systems (ECS) marque. The current state-of-the-art knowledge appears on his web-site and is distilled in two technical papers published by the society’s Electrical Group, Nos. 68 and 82.

Click here for details of the group and a full index of its papers. With luck, my continuing research will throw up some more flesh for Martin to add to the tale.

What became of the London sundial column?

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My previous blog was about the sundial column at Seven Dials in central London. It is a reconstruction, erected in the 1980s to replace a column that had been there since 1694 but was taken down in 1773.

Popular legend has it that it had been ruined by a search for treasure presumed to be buried under it. Perhaps more truthful is that it was removed because the place had become a meeting-point for riff-raff. Whatever the reason, it was demolished and its remains landed in an architect’s garden in Addlestone, Surrey, southwest of London.

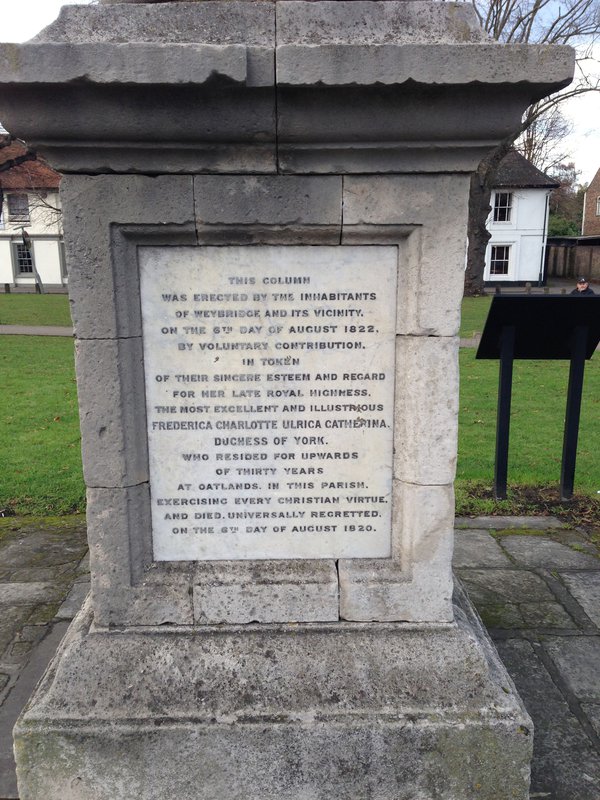

But fifty years later it was given a new lease of life in nearby Weybridge. The column was erected by public subscription in 1822 in memory of Frederica, the Duchess of York (1767-1820) who had been a popular local benefactress. It was decided that the dial stone was too heavy to cap it. A ducal coronet was used instead and the base inscribed to the Duchess. Two centuries later, the York Column at Weybridge still stands on what is named Monument Green.

The original late 17th-century dial stone was used as a mounting block, to help the young or elderly or infirm to mount and dismount a horse or cart – not the best way to preserve a finely sculpted object. But this too has survived. More than three centuries old, and much the worse for wear, it lies to the west side of Weybridge Library. A plaque explains the historical significance of what to the average passer by must seem a very unassuming bit of stone.

My thanks go to AHS member Hugh Cockwill who lives nearby and took the photos at my request.