The AHS Blog

300 years

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

This year saw the tercentenary of the death Thomas Tompion (b.1639), the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’ and his life is celebrated in two special exhibitions: the first at the British Museum, entitled ‘Perfect Timing’, which focuses on the magnificent Mostyn Tompion and the second, ‘Majestic Time’, at the National Watch and Clock Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Tompion enthusiasts should be further delighted by the announcement of the forthcoming publication of ‘Thomas Tompion, 300 years’. The book promises a wealth of new detail, fresh illustrations and includes Jeremy Evans’s previously unpublished chronology of Tompion’s life.

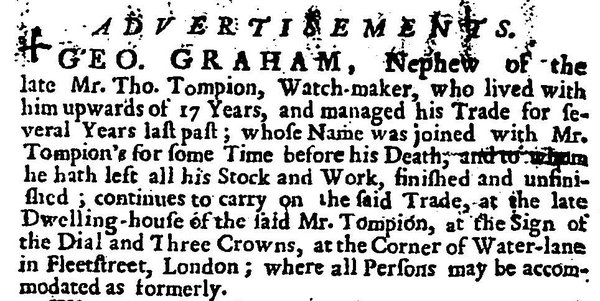

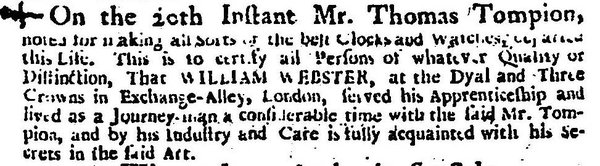

This tercentenary marks not only an end, but a new beginning as Tompion’s nephew by marriage and then business partner, George Graham (c.1673-1751), inherited and continued the business at the corner of Water Lane. As far as I am aware, the earliest announcement of Graham’s succession was first advertised in The Englishman one week after the death .

William Webster, however, did not show the same reserve. He had an advert published the day after Tompion’s death in two papers: The Mercator or Commerce Retrieved and The Englishman. His announcement of the death was a thinly veiled attempt to attract business and was repeated in various papers that week.

Unlike Webster, Graham was not apprenticed to Tompion (several publications incorrectly cite Graham as being so). He joined the household sometime around 1676 after gaining his freedom from apprenticeship to Henry Aske.

Evidence suggests that Graham did not serve his entire apprenticeship under Aske and it is currently a mystery as to where he was during the last years of his apprenticeship.

Looking forward to next year there is another important tercentenary, that of the Queen Anne Longitude Act. George Graham played an important role as an encourager and advisor to both Henry Sully and John Harrison in their efforts to produce sea-going clocks and will feature in a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum next year.

Happiest days of your life?

This post was written by James Nye

Recently we hosted the BHI North London branch at The Clockworks. It was a great visit, filled with observations and anecdotes about life among clocks.

Always popular, we looked at the Gent’s 'waiting train’, or ‘motor pendulum’. A neat design, synchronised to an accurate source, it has the power to overcome harsh winds or snow impeding the hands, compensating with more frequent impulses when needed.

Chatting over a coffee, stories emerged of people’s introduction to clocks and watches – particularly electric ones.

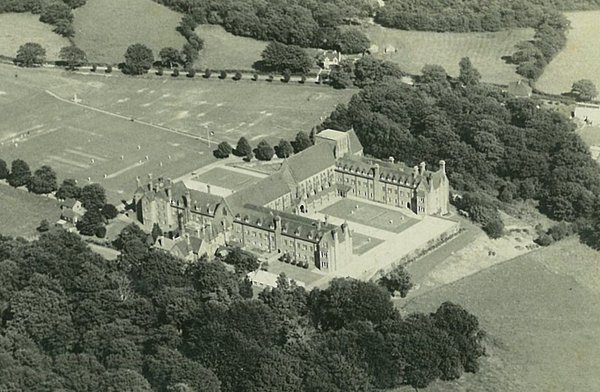

I described how, at the age of 13, I was put in charge of my school’s Gents-based clock system (for the nerds, C7, C69, C150 etc), including a waiting train in a tower above. One guest mentioned that coincidentally it was the same for him – being asked to tend to just such a school system.

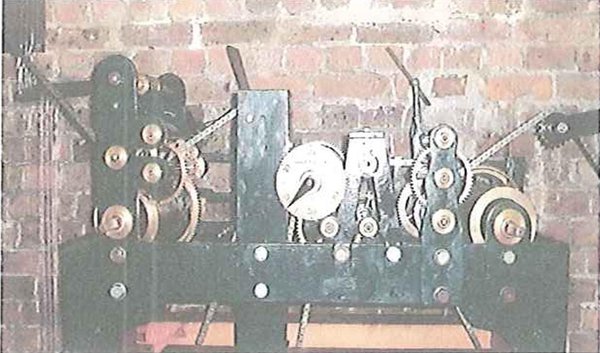

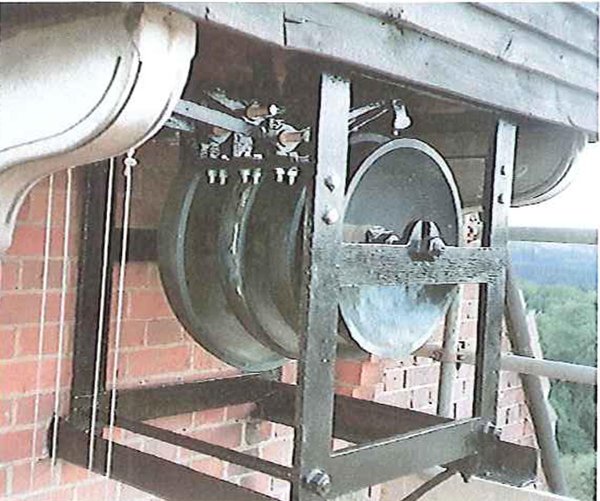

This prompted me to describe a feature of the system I maintained. A flatbed turret clock (David Glasgow, 1911) provided a chime and strike on bells, tripped by a solenoid, in turn controlled from the waiting train, using four aluminium sails (like a windmill) mounted on the bevel nest, operating each quarter on a microswitch – an ingenious addition.

‘Which school was this?’ asked a misty-eyed guest. ‘Ardingly College’, I replied. ‘That was me,’ he said softly, ‘probably in 1950.’

A quarter century apart, we had both been responsible for the same system. George D’Oyly Snow, headmaster, was fed up with chimes sounding at the wrong time, and with limited funds, but knowing the inventive skills of his boys, he commissioned my guest to find a solution – a solution still functioning into the late 1970s.

A theme I mentioned in a recent lecture is the serious risk to which electric clock systems are subject when their caretakers or installers move on.

The Ardingly Gent system, probably in service since the 1930s, was replaced after approximately 60 years by a radio-controlled master clock, and Thwaites & Reed recently reworked the flatbed movement, installing motor-wind, and even synchronization.

George Snow can rest easy in his grave – the chimes still sound on time. But to my mind they must sound a plaintive note as well – curiously, I feel desperately cheated of part of my heritage, and I know someone else who probably feels the same way.