The AHS Blog

'A Visit to the Science and Art Museums'

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1932, the Trinidadian historian and writer, Cyril Lionel Robert (C.L.R.) James, then aged 31, visited the Science Museum in London.

'I hadn’t intended to spend much time there', he wrote. 'I was on my way to the Victoria and Albert Museum. But one of the men I was with, John Ince, is clever at engines and, at least to an ignoramus like myself, learned in the mysteries of mechanics. He persuaded me to go in and, I do not know why, the place had a surprising effect on me.'

The museum had only been open in its present building on Exhibition Road for some five years when James visited. He was, as he described, 'knocked silly' by the sight of a racing seaplane in the front hall, 'one of the most beautiful things I have seen in London.'

But after James had viewed the Science Museum’s aircraft collection, he made his way to the time measurement display and stood gazing at the huge clock from Wells Cathedral, constructed in 1392 and moved to the Science Museum in the nineteenth century where, he observed, 'it ticks serenely on, striking the quarters and the hours, and keeping much better time than the brand-new watch which I bought two weeks ago'.

Standing in front of this iconic clock, James was struck by a feeling of mortality. 'I had a good look at that old clock', he remarked. 'I couldn’t help remembering with envy that in a few years I would probably be gone, while the old beast would probably be there in a thousand years, tick-ticking away, living his narrow but peaceable life.'

It was not until 1989, 57 years after his visit to the Science Museum’s clocks gallery, that C.L.R. James finally passed away, aged 88, in a small flat in Brixton. He had achieved many great things in his momentous life. But he was right: the Wells Cathedral clock keeps on tick-ticking at the Science Museum, over 600 years since it was first set going. And it still offers attentive visitors pause for thought, as it did in 1932.

Turret clock specialist Keith Scobie-Youngs will be speaking about the Wells Cathedral clock (together with other ancient timekeepers) at the AHS London Lecture Series on 20 March 2014. Check the AHS website nearer the time for more details.

Wake up – tea’s up

This post was written by David Thompson

What a treat to be able to wake up in the morning to a ready-made cup of tea and to be grateful to a machine for producing it automatically. Many of the older generation will remember a machine for just that purpose, a machine which was always referred to as the Teasmade.

Probably the one we all remember was the Goblin Teasmade but there were many others and the originally idea has its origins at the end of the 19th century with Mr. Rowbottom’s 1891 patent – with an automatically lit gas burner to heat the water in the kettle and then the machine would pour the boiling water into a tea-pot to make the tea, I can just see the warning notice on such a machine today – well not really as such a fire hazard would not be put into manufacture today.

There is a fine example of an Albert E. Richardson machine in the Science Museum to give an idea of what the early machine were like.

I was intrigued by this subject from seeing the Teasmade on exhibition in the British Museum clocks and watches gallery and it lead me to a splendid account of the history of the automatic tea maker written by David Stoner and published as a chapter in Clifford Bird’s book on Metamec, published by our own society and still available today at a give-away price.

All the original machines were clockwork, controlled by a simple alarm clock mechanism so you got the wake-up bell and the ready-made cup of tea, almost guaranteed to be luke warm. Many people swore by them and I don’t doubt at them. Nevertheless, a great idea.

Time and efficiency

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

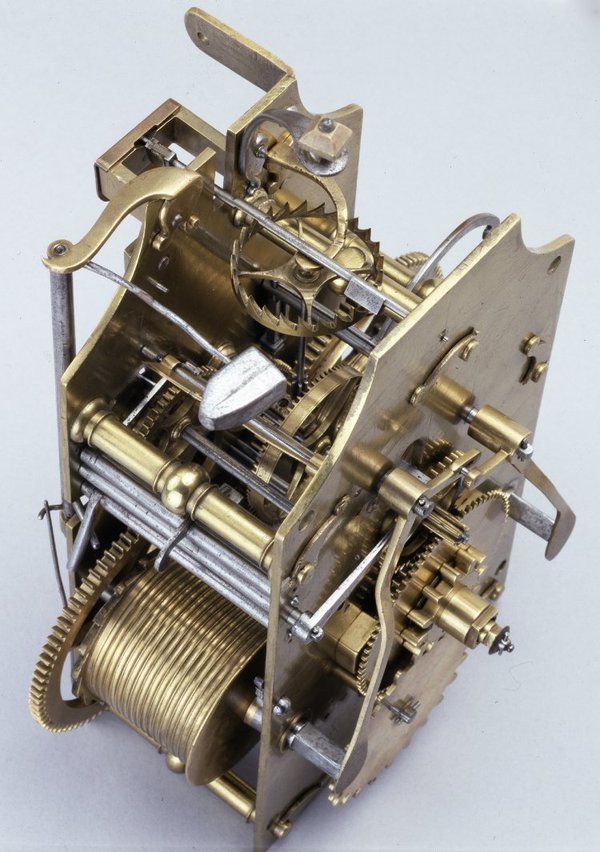

Last time I looked at how clocks and watches obtain and store their energy, but I thought it worth mentioning how carefully they use it.

Some clocks are designed to have a surfeit of energy – for instance turret clocks must be able to overcome ice and snow loading. But, in general, efficiency is paramount in horology.

A 17th century eight day longcase clock typically runs on a 12lb weight (5.44kg in new money) which drops about 5 feet in the eight days. Based on those numbers, my dimly recollected school physics tells me that such a longcase clock must use about 1/8500th of a Watt of power.

Let us compare that with something familiar. The best example I can think-up is the motor that vibrates a mobile phone – these run at about 0.16W – i.e. that little motor that tickles in your pocket could run about 1500 longcase clocks. Or, looking at it another way, the energy used to boil an egg would keep a longcase clock going for 80 years. Not bad for a 300 year old machine.

The Atmos clock (which I mentioned before for its ability to be powered by changes in air temperature) is in another league – the little mobile phone motor could run 700,000 of them. 1 boiled egg, 38000 years.

How are they so much more efficient than the longcase clock? Apart from being closer in scale to watch work, the Atmos clock benefits from 250 years of horological development. They are factory made, not hand made – this facilitates much closer tolerances and optimal gear tooth shapes. Like fine watches, their bearings are jewelled (jewels are little rubies with holes drilled in them – very smooth and very hard wearing). They also have a steel torsion pendulum which is excellent at conserving energy.

Something else to bear in mind is that we expect our clocks and watches to run non-stop for years on end, between services, without breaking down. Do you ask the same of your car? Remember that when your clock repairer presents their next bill to you!