The AHS Blog

Clocks in Berlin museums

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Every year the AHS organizes a Study Tour for members to see collections of clocks and watches abroad.

The 2010 tour went to Germany and included two days in Berlin. As reported in Antiquarian Horology March 2011, they saw many fine clocks in the Charlottenburg Palace, as well as in the New Palace of Sanssouci in nearby Potsdam.

Last month I was in the German capital myself, and had a chance to visit some of the many other museums, and spotted further items of horological interest. The German Technical Museum has an impressive railway collection in two former loc sheds. In the entrance building they display the clock of the railway station of Breslau (now Wroclaw), dated c. 1850, complete with its vertical lead-off work and the dial. Next to it is an earlier turret clock, with stones as weights for the going and striking train, as well as – perhaps more unusually – for the pendulum bob.

Opposite Charlottenburg Palace is the Bröhan-museum, specialised in Art Nouveau, Art Déco and the Berlin Secession. Among the treasures of applied arts in ceramics, glass, wood and metalwork were two mantel clocks in Art Nouveau (also called Jugendstil) style, and a clock with ‘TEMPUS FUGIT’ (Time Flies) on the dial instead of numerals.

Any music lover will enjoy the Museum of Musical Instruments, located behind the famous Philharmonie concert hall and built by the same architect, Hans Scharoun.

Among the hundreds of historic instruments are two more than man-sized musical clocks. Both are among the dozens of instruments that can be heard on the audioguides supplied at the entrance. What a treat to hear these gentle sounds in the knowledge that traffic noise is just on the other side of the wall.

Job done!

This post was written by Matthew Read

Public clocks that don’t work; there are thousands of them. An irritation, sign of the neglectful and difficult times or simply a reflection of the lack of need for the dissemination of time in that format? Big questions but in this case a relatively simple solution with interesting conservation issues thrown in.

The plan to reinstate the long-dilapidated village hall clock with a modern equivalent. Easy reliable low maintenance solution? But what actually happened to the earlier clock? Did it still exist? Could it be reinstated? Questions sometimes make things more complicated but in this instance, the result was felt to justify the extra energy.

The re-discovered clock was probably originally installed in the 1930’s; Smith mains synchronous movement with hand setting by leaning out of the window to reach the adjusting knob. Although potentially perfectly serviceable, due to the mains voltage and window leaning out of combination , it was decided to replace the movement with a low-voltage slave, controlled from inside the building (the original movement packaged within the clock case.

The painted aluminium dial had discoloured with parked hands and some corrosion. Repainting the dial would have obliterated the original/existing surface so a decision made to copy the dial on the reverse, thus preserving what existed and the dial was turned inside-out.

Happy villagers, public time restored, happy conservation compromise, job done.

The Empire Hall was built in 1907 for the village by James Buchanan (later Lord Woolavington) of Lavington Park.

Time on the BBC

This post was written by David Rooney

A couple of weeks ago, BBC radio listeners around the world celebrated the 90th anniversary of the corporation’s founding as the British Broadcasting Company.

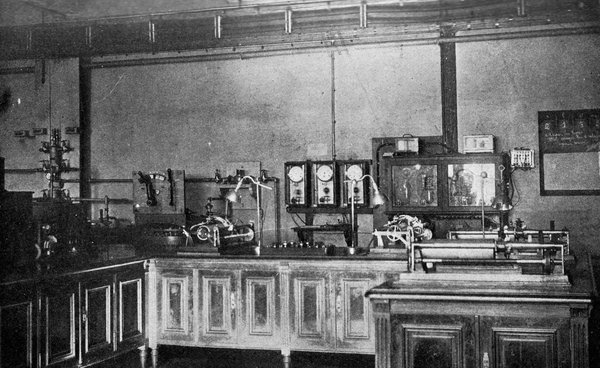

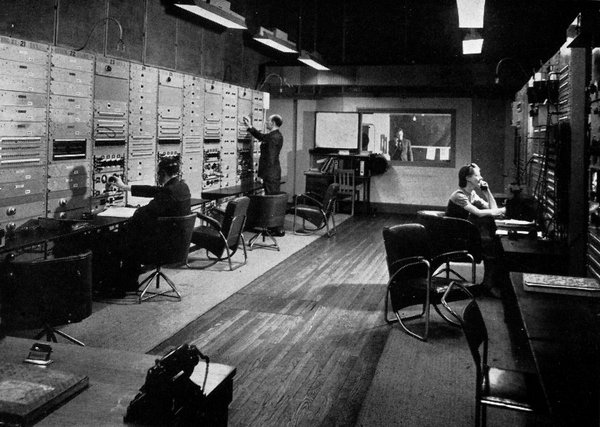

On 14 November, a special edition of Simon Mayo’s Drive Time show was broadcast live from the Science Museum, London, in front of the first BBC transmitter, known as ‘2LO’. It’s on show as part of a free temporary exhibit.

Radio broadcasting changed the face of timekeeping. When the BBC was founded in 1922, wireless time signals had been around for about a decade, transmitted from the Eiffel Tower, but they were for specialists, not the public. The BBC brought accurate Greenwich time into the living rooms of the nation.

The first BBC time signals came from the announcers reading out the time. Within a year, a special set of tubular bells was in use, sounding time by the Westminster chimes. But in 1924, the now-familiar ‘six pip’ time signal began. And it’s still in use today – although listeners on digital radio hear the signal a couple of seconds late. Progress, I guess.

But the six pips wasn’t the only time signal set up by the BBC in its earliest years. The familiar sound of Big Ben was also captured live by BBC microphones from 1923 – and that system too is still in place.

It’s time, I’m afraid, for the inevitable plug: to find out more about time signals on the BBC, try my book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady. In it, you can discover why Dame Nellie Melba had reason to say, ‘young man, if you think I am going to climb up there, you are greatly mistaken!’

Happy birthday, BBC…