The AHS Blog

Backwards and forwards

This post was written by James Nye

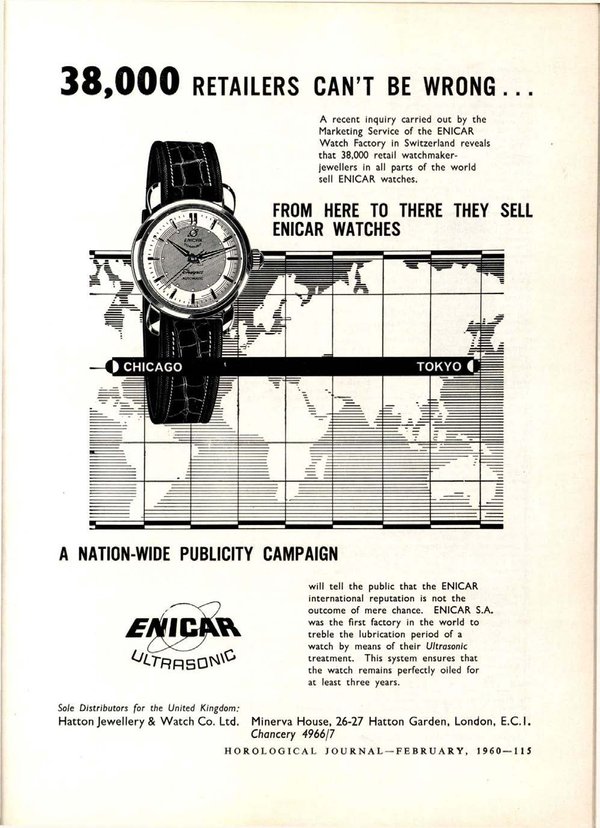

I am shocked to realise it is now a decade since I blogged about Enicar watches. As collectors know, Enicar derives from reversing the family name of the owners, Ariste and Emma Racine. Signing clocks and watches like this has a long tradition, with an interesting variety of explanations.

Back in the December 1993 issue of Antiquarian Horology, Sebastian Whitestone discussed some watches that bogusly claimed a London origin, but which in reality were from the Friedberg region and signed Lekceh, Legeips, Rengaw, Renpuarg and Ysorb. Reverse these and we have the less exotic Heckel, Spiegel, Wagner, Graupner and Brosy.

Mirrors reverse images, and tellingly, Spiegel also used the giveaway signature Miroir, London. The word ‘spiegel’ is German for mirror, and thus another pun.

But not all Friedberg makers reversed their names when they added a London location. Eckert and Schreiner signed (falsely) from London, but used their normal names.

Surveying the Ashmolean Museum's watches in the December 2000 issue of AH, David Thompson enlarged the geography, tying a watch signed ‘Renpuarg, London No. 4’ to Augsburg.

Alice Arnold Becker revisited backward signatures in AH in June 2014, taking the line that it was all marketing. The watchmakers perhaps falsified locations to secure the gravitas and caché of the London market – creative branding, familiar today.

Dutch horologist John Selders has also studied this phenomenon, publishing several pieces in Tijdschrift and summarising in 2015 with a list of 24 such reversed names, from the late seventeenth century to the turn of the nineteenth, and noting that some makers signed from Paris, not just London.

Strangely, precisely the same thing happened in Britain. English and Scottish makers of watches also reversed their names. An example is a watch by James Peddie of Stirling, signed on the back plate Jas Eiddep (see Clocks, April 2019). More prolific is Eardley Norton, whose signature Yeldrae Notron appears with surprising frequency. Usher & Cole’s apprentice John Wontner later signed objects as Rentnow. Cole signed as Eloc.

What on earth were all these people doing? There are several theories. Some assume distant makers wanted to capture borrowed prestige, and value, by signing from London, or Paris – an element of passing-off. A false signature disguises true authorship.Some suggest it was done to avoid taxes. Perhaps it limited redress to a real maker. Or perhaps it shows the maker’s sense of humour?

Does it all echo the original Rolex/Tudor division – an affordable product from the same stable, but differentiated?

No firm conclusions are possible, but some theories are surely too far-fetched. Tax officials won’t be fooled by mirror-writing. Signing a watch carries a maker’s chosen identity out into the world, and should be permanent, and memorable. A sense of whimsy could be involved, maybe even a sense of a brand that stands on its own, distinct from the name of the controlling mind involved.

In all, a subject that deserves more than a backwards glance... and if anyone has any other examples of reversed clock and watch signatures, please do tell me!

The watches of Samuel Pepys

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

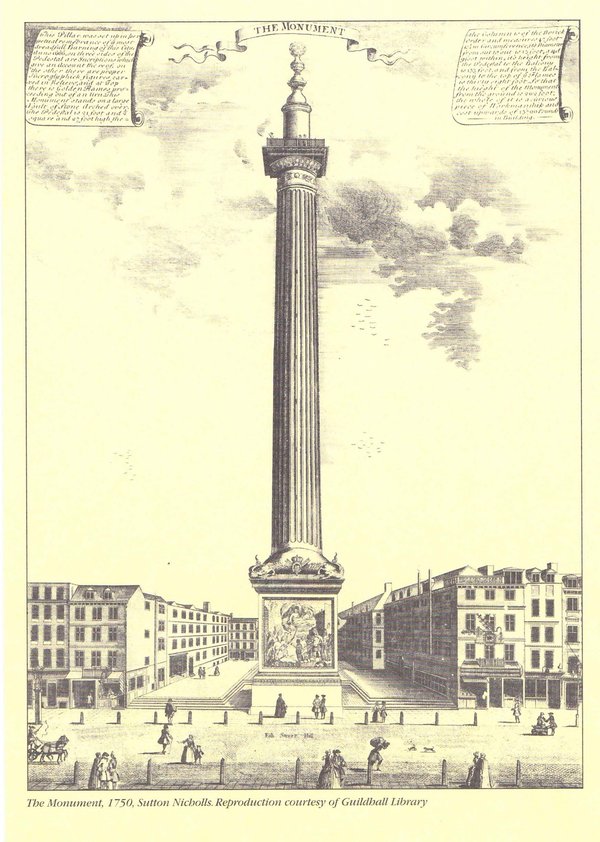

The office of the AHS in Lovat Lane in the City of London is a stone’s throw away from The Monument, erected to commemorate the Great Fire of London of 1666.

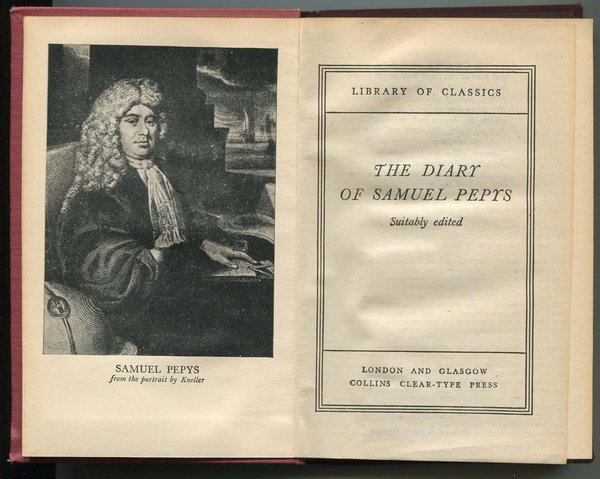

The fire was famously reported in The Diary of Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), which ‘is unique, no less for Pepys’s self-revelation, than for its graphic picture of social life at the time of the Restoration’. This is a quote from the preface in my copy of the Library of Classics edition first published in 1825. Running to 640 pages, it yet contains scarcely half of the manuscript. It had also been ‘suitably edited’, which perhaps means that for example anything to do with his bodily functions or his amorous exploits had been removed.

A more complete edition appeared in 1893, and this forms the basis for a magnificent website which offers ‘the full text of his diary, along with several letters sent or received by Pepys, plus thousands of pages of further information about the people, places and things in his world’.

It is searchable, and if you want to find out what Pepys wrote about clocks and watches, you will find some two dozens entries.* Let’s follow one trail, all to do with watches:

Monday 17 April 1665: 'This day was left at my house a very neat silver watch, by one Briggs, a scrivener and sollicitor […].'

Friday 12 May 1665: 'To the ’Change [the Royal Exchange] and thence to my watchmaker, where he has put it [i.e. the watch] in order, and a good and brave piece it is, and he tells me worth 14l. which is a greater present than I valued it.'

Saturday 13 May 1665: 'To the ’Change after office, and received my watch from the watchmaker, and a very fine [one] it is, given me by Briggs, the Scrivener. […] But, Lord! to see how much of my old folly and childishnesse hangs upon me still that I cannot forbear carrying my watch in my hand in the coach all this afternoon, and seeing what o’clock it is one hundred times; and am apt to think with myself, how could I be so long without one; though I remember since, I had one, and found it a trouble, and resolved to carry one no more about me while I lived.'

Wednesday 13 September 1665: 'Up, and walked to Greenwich, taking pleasure to walk with my minute watch in my hand, by which I am come now to see the distances of my way from Woolwich to Greenwich, and do find myself to come within two minutes constantly to the same place at the end of each quarter of an houre.'

Friday 22 December 1665: 'I to my Lord Bruncker’s, and there spent the evening by my desire in seeing his Lordship open to pieces and make up again his watch, thereby being taught what I never knew before; and it is a thing very well worth my having seen, and am mightily pleased and satisfied with it.'

Saturday 22 September 1666: 'My Lord Brunck […] now give me a watch, a plain one, in the roome of [instead of] my former watch with many motions which I did give him. If it goes well, I care not for the difference in worth, though believe there is above 5l.'

All this is very interesting, but it leaves questions unanswered.

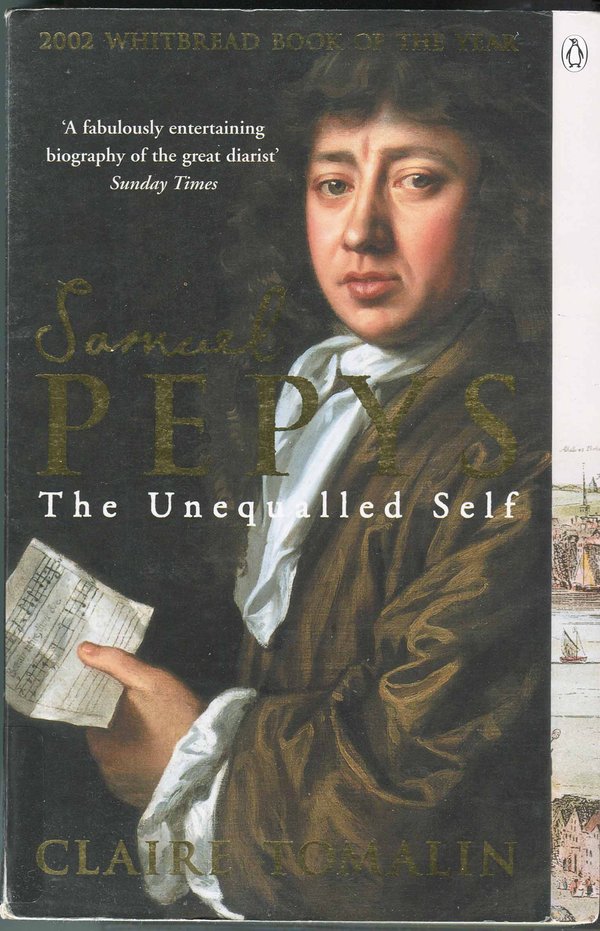

Why was Pepys given a watch 'by one Briggs, a scrivener and sollicitor', about whom we hear no more in the diary, and who is not mentioned in Claire Tomalin’s excellent biography published in 2002? Did he want to curry favour with Pepys, perhaps hoping to benefit somehow?

We are not told the name of the man who had serviced his watch, nor do we have details of the watch except that it was worth £14 and came 'with many motions', which we take to mean that it not just showed the time but also had additional functions that could make a watch such an attractive possession.

But why, we may ask, had Pepys earlier in his life been so frustrated with a watch? Had it malfunctioned?

His wife had her own watch (Saturday 9 February 1666/67: 'This noon come my wife’s watchmaker, and received 12l. of me for her watch') but it led to irritation (Wednesday 3 April 1667: ‘and to bed, vexed … that my wife’s watch proves so bad as it do').

Or had it been the anxiety that a watch could draw unwanted attention, like we hear these days of brutal daylight robberies of expensive watches? On Wednesday 1 January 1667/68, Pepys ‘took coach and home about 9 or 10 at night, where not finding my wife come home, I took the same coach again, and leaving my watch behind me for fear of robbing, I did go back.’

If he was so taken with his fancy watch that he could not stop consulting it when he set out with it in his coach, why did Pepys later give it away to William Brouncker (c. 1620–1684), and accepted a simpler and less valuable one in return?

Lord Brouncker was from 1662 to 1677 the first president of the Royal Society, an office to which Pepys himself was to be appointed in 1684, long after he had stopped writing his diary.

Brouncker features prominently in Pepys’s diary; they were neighbours and on friendly terms. So perhaps Pepys gave him his fine watch simply from the goodness of his heart, and that is a nice note to end on.

* Searching on ‘clock’, one must weed out hundreds of 'o’clocks', and ‘watch’ is of course often found to mean ‘look at’, but with some patience I found 23 pertinent entries which I shall be happy to share with anyone interested.