The AHS Blog

Musical clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

My previous post in this blog was on clocks in opera. How about opera in clocks?

The Handel House Museum is the London home where the composer George Frideric Handel lived from 1723 until his death in 1759. In the 1730s, Handel provided music for a series of musical clocks created by the watch and clockmaker Charles Clay.

These more than man-sized, elaborate pieces of furniture were fitted with chimes and/or pump organs that at the hour and every quarter played musical excerpts from popular operas and sonatas.

Until 23 February the Handel House Museum presents an overview of Clay’s clocks in an exhibition ‘The Triumph of Music over Time’. The centrepiece is a clock on loan from the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; other clocks are presented as photos on text panels.

These panels are all on-line here where you can also listen to some of the music that Handel arranged for Clay’s musical clocks, including two pieces from his opera Arianna in Creta. So there you have it: opera in clocks.

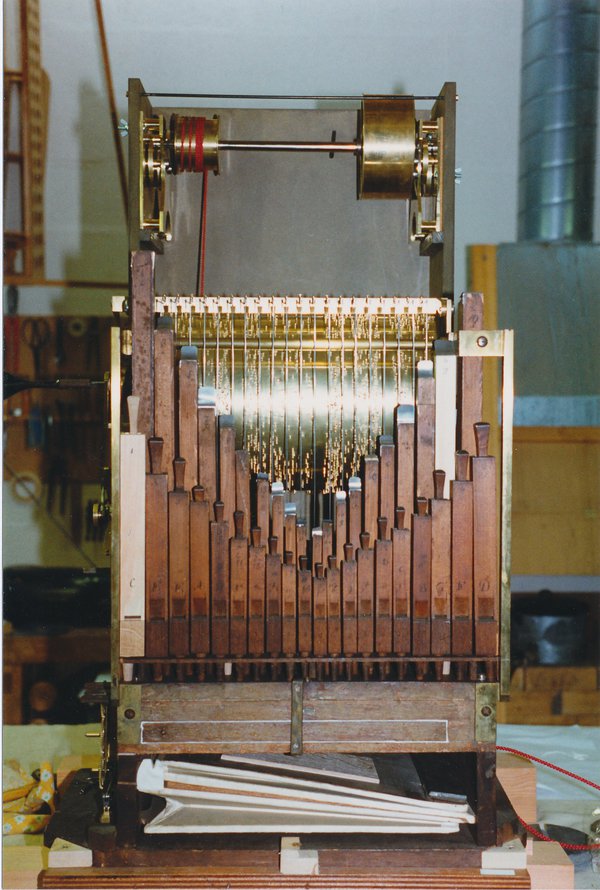

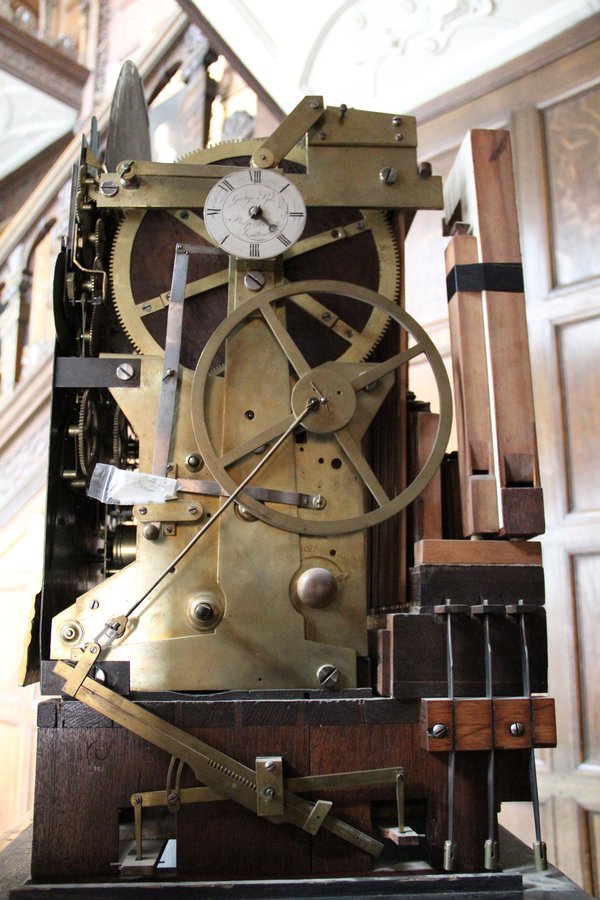

Another 18th century maker of beautifully crafted musical clocks was George Pyke. A fine example, dated 1765, is on display at Temple Newsam House in Leeds.

Standing over 6 foot tall on its pedestal, it strikes the hours and has a pipe organ that plays eight tunes. The innards of the Pyke clock are shown below; more photos and details of the clock are here on the website of Brittany Cox, who has made a condition study of the clock and hopes one day to be able to restore it to its former glory.

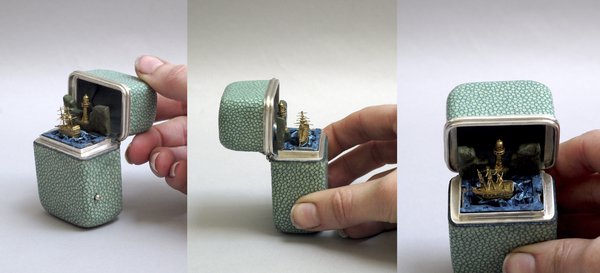

Although a bit off topic – it is not a clock – you may like to know of a musical automaton that Brittany Cox restored to working order during her studies at the Clocks and Related Dynamic Objects Department at West Dean College. A miniature ship, a mere 15mm wide, rocks to and fro, as in a storm, while ‘God Save the King’ plays on a plucked comb; see and hear it here.

For this project Brittany was awarded the annual AHS prize for 2012. For a full description see this article which she wrote for our journal Antiquarian Horology .

With thanks to Ella Roberts, Communications Officer at the Handel House Museum, for her help.

A million free images

This post was written by David Rooney

Just before Christmas, the British Library released over a million historical images from its printed collections onto the image-sharing website Flickr. The images are out of copyright and the library has made them available with a Creative Commons licence which, in short, encourages anybody to use, remix and repurpose them, so long as they respect a few ground rules.

This is a remarkable resource of imagery and will be a boon for anybody carrying out historical research – such as AHS members.

There are countless images of interest in this release, each one of which might augment an existing research project or prompt a new one. The beauty of archives such as this is the opportunity for lateral thinking. You might be researching a particular village, or writer, or building, or period. And you might find an image here that opens up new avenues of research.

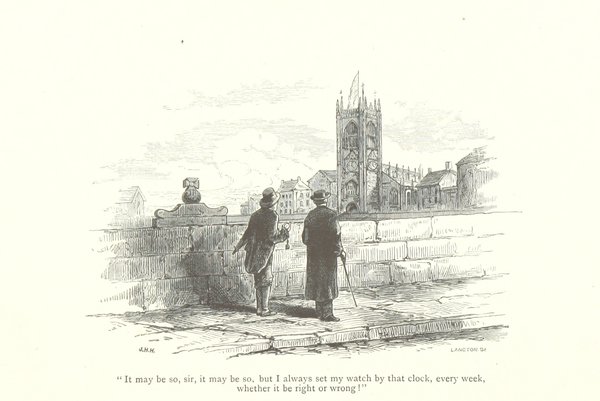

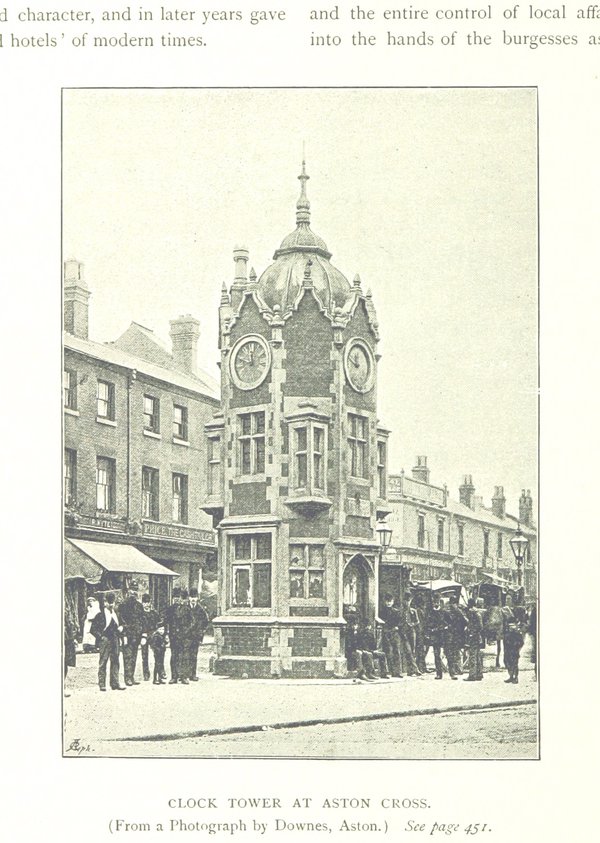

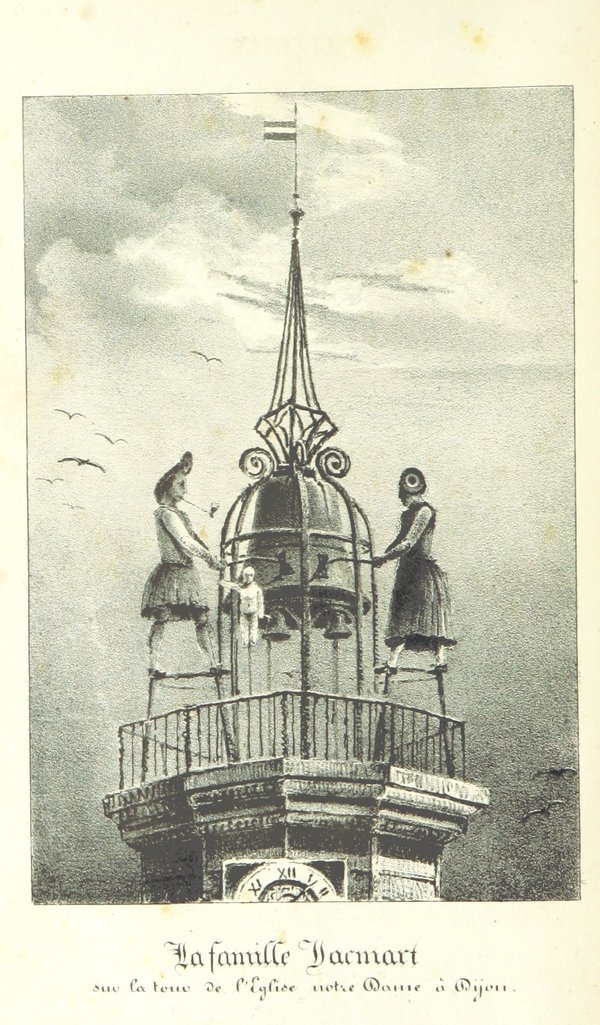

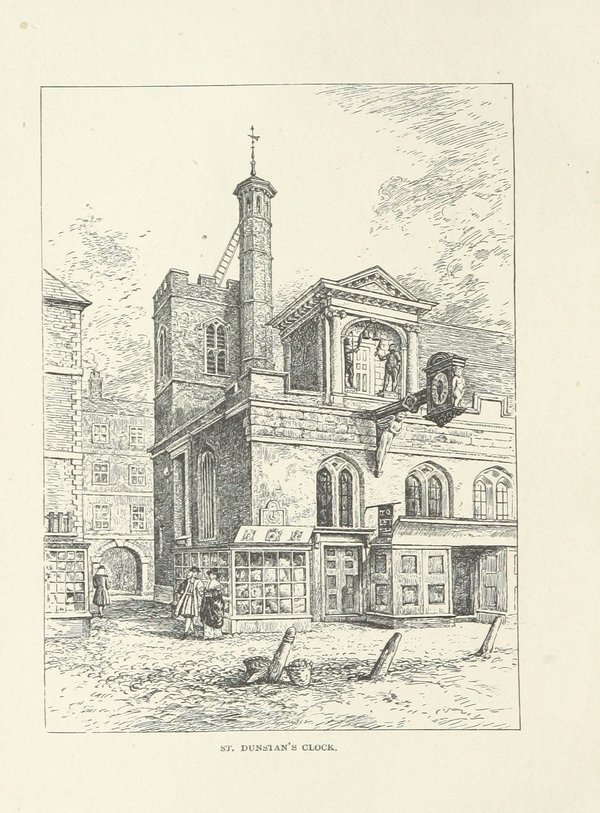

The first four images I found are the result of searching for ‘clock’ or ‘clocktower’ – as you’d expect, lots of public clocks.

But let’s say I’m interested in chronometers. Unfortunately there are no search returns for that word. But then I tried searching for ‘observatory’, and found this image.

It’s from a book on the North Polar Expedition, and it’s a photograph of marine chronometers on show in a US Navy centennial exhibit in 1876.

That led me to this catalogue of the objects exhibited. And on pages 79–81 there’s a remarkable and detailed description of the use of chronometers at the US Naval Observatory in the 1870s. Serendipitous discovery is a wonderful thing.

You’ll probably want to put aside an hour or two browsing these images – and a lot more time following the interesting leads they throw up! Happy hunting, and happy new year.

The sands of time

This post was written by David Thompson

Everyone is familiar with the egg timer, but just how far back in history do these glass timers filled with free-flowing material go?

The earliest known illustration of such a device exists in an Italian fresco dating from between 1337 and 1339 in the Palazzo Publico in Siena. The fresco is called ‘The Allegory of Good Government’ and in it, one of the figures can be seen holding a sand-glass.

Before modern glass making techniques developed, sand-glasses were made using two separate bulbs bound together around a disc with a hole for the ‘sand’ to pass through. Over the centuries all manner of different materials were tried in attempts to achieve a uniform free-flowing performance.

The duration of the timer depended firstly on the amount of ‘sand’ in the glass, and secondly on the size of the opening between the two containers. The two glasses were sealed together with wax and the joint covered and tightly bound. The biggest enemy for these glasses was humidiy – damp ’sand’ was bad for business.

A particularly fine example exists in the British Museum collections, although is has a rather dubious reputation.

It is a composite glass with four separate glasses in a beautiful ebony frame and each glass is designed to run for a different period, one quarter, one half, one three quarters and last a full hour. It even boasts a leather carrying case.

At one time it was said to have belonged to Mary Queen of Scots and indeed, at the top and bottom of the frame are reverse-painted glass discs bearing the royal shield of the Tudors and the shield of France with fleur-de-lys. The idea was that this glass was owned by Mary Queen of Scots and Francis II, king of France.

Unfortunately, the Tudor arms are from the wrong period and the lion rampant in the first quarter of the shield is the wrong way round. The leather case is also roughly embellished with the monogram MF for Mary and Francis.

In spite of its later enhancement, this is nevertheless a very fine example of a late 17th century glass.

On the one hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

The last of the five elements is the indicator, the part of the clock or watch that conveys the time.

Early clocks and watches typically only had a single, hour, hand. This was more than adequate for indicating the time as these foliot-controlled timekeepers would typically lose or gain at least quarter of an hour in a day. Minute and seconds hands only became truly useful with the vast improvement in timekeeping that came with introduction of the pendulum in 1657 and the balance spring 1675.

However, the familiarity, simplicity and economy of the single hand meant they never became obsolete. Throughout the 18th century, pendulum-controlled longcase clocks with single hands were very popular in the provinces of England.

There were also some more interesting implementations of the single hand. This balance spring watch has a six-hour dial, instead of the usual twelve-hour dial. With only six hours dividing the circle it offers twice the resolution of a standard twelve-hour dial, thus going some way to making up for the lack of a minute hand.

Next, a single hand with a difference – it is telescopic. The hand extends and retracts to follow the contour of the oval dial, allowing the time to be read clearly. A fixed hand would fall short at the “XII” or “VI” positions, making it harder to read with accuracy.

Another form of single hand can be found on this Japanese pillar clock.

The pendulum controlled movement is at the top of the clock. Below it, the single, hour, hand is directly attached to the driving weight through a slot in the case. As the weight descends over the course of a day, it indicates the time against the linear scale of numeral plaques on the case. The plaques can slide, which allows their positions to be adjusted for the Japanese system of unequal hours.

Single handed watches continue to made by several manufacturers, such as this example owned by myself.

In practice, the time can only easily be read to the nearest five minutes (which is well within the capabilities of its modern movement). However, I find that this is good enough (at the the weekends at least!) and it is a most leisurely way to follow the time.