The AHS Blog

A woman horological collector

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The AHS has recently paid attention to a number of Great Horological Collectors, with lectures that were later reported in the journal. All these lectures were about men.

That a woman could also assemble an important horological collection was demonstrated by the Austrian author Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830-1916). She had received practical training as a watchmaker and brought together a collection of 270 pocket watches dating 16th-19th century.

In 1917 it was purchased for the newly founded Wiener Uhrenmuseum, where the collection (sadly reduced to a mere 47 during World War II) is on display in a special room.

Her horological expertise and her love for her collection are reflected in her short novel Lotti die Uhrmacherin (Charlotte the Woman Watchmaker) of 1889.

Lotti is the daughter of a master watchmaker and is herself skilled in the craft. She inherits her father’s valuable collection of watches and refuses offers from other collectors, until her former fiancé gets in financial trouble. She relents and sells the collection, to be able to support him (anonymously).

Chapter 3 describes the collection in remarkable technical and historical detail, and names many makers – Le Roy, Breguet, Tompion and Mudge, to mention just a few.

Further reading: Eva-Maria Orosz, ‘“My watches make it hard for me to die”. Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach: the writer as watch collector’, pages 10-13 in Highlights from the Vienna Museum of Clocks and Watches (Vienna, 2011); I thank Fortunat Mueller-Maerki for bringing this essay to my attention. There is no English translation of Lotti die Uhrmacherin , but a freely downloadable edition with some English annotation is on-line here.

A multiplicity of times

This post was written by David Rooney

David Thompson’s post about Metamec ‘time savings’ clocks excited me, because I am interested in the wider cultural meanings around seemingly innocuous phrases such as ‘time is money’.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on the subject for the Science Museum’s ‘Ingenious’ website. It looked at the history of Benjamin Franklin’s 1748 phrase and how its meanings in different times and places varied.

Reading the article back, I have been reminded of a fascinating book by anthropologist Kevin Birth called Any Time is Trinidad Time (University Press of Florida, 1999).

Here’s what I wrote for the Science Museum:

'Trinidad, a Caribbean island between Venezuela and the USA, has a rich history of settlement and immigration. It is ethnically and culturally highly diverse, with residents of mainly Black and Indian origin mixing with Spanish, French and English colonial culture.

'Social anthropologist Kevin Birth spent time living there in 1989 in order to study cultures of timekeeping. Starting out with the often-used phrase "any time is Trinidad time", originally attributed to calypso singer Lord Kitchener, Birth explored the ways people come together with differing notions of timekeeping, and how conflicts are managed.

'He also looked at phrases like "time is money", "time management" and "budgeting time" and found that their use and meaning is highly complex and culture-specific. Generalisations were impossible.

'We all carry around with us a great variety of "personal times" – value systems linking time with activity – and we deploy them in highly complex ways according to culture, context and circumstances. Phrases like the Lord Kitchener lyric are complex devices used to oil the wheels of societies under time pressure.'

If you’re interested in how different societies use clocks, I can heartily recommend reading Birth’s book.

Money saving time

This post was written by David Thompson

There would be a knock at the door and my mother was busy. She would say 'that will be the insurance man – answer the door and give him this money and tell him the number is 16251'.

Many of us remember these numbers rather in the same way that anyone who did national service or served in the regular armed forces will surely remember their ID number.

In 1954 the Time Savings Clock Company Limited and Metamec of Dereham applied for a patent for a clock which would only go when coins were placed in a slot in the top of the case. Two florins weekly it says on the coin slot in the case top.

For people on insurance schemes with companies like the Co-operative in the 1950s, four shillings was quite a lot on money to put aside each week. The idea of the clock was to help people hold on to their money to pay the premium each week.

The system was invented by William Arthur Pitt and the patent was granted to the Time Savings Clock Company of Manchester (no.772,762). The mechanism consisted of a series of levers and wheels which arrested the going of the clock to which it was fitted until coins were inserted to release it and thus allow the clock to run.

These coins, after operating the levers would fall into the space at the bottom of the clock case, covered by a wooden panel which fitted over a stud and was closed by a wire and lead seal applied by the insurance man. When he called he would cut the seal, empty out the money and re-seal the back until his next visit – simple.

A full account of these clocks and many more everyday clocks can be found in Clifford Bird’s book – Metamec Clock Maker Dereham published in 2003 by the Antiquarian Horological Society.

Making a 19th century battery

This article was written by Francoise Collanges

My MA project involves making a copy of elements of a mid-19th century electro-mechanical clock in order to see what the process could bring to conservation as a research tool.

One question was how the clock was originally powered and would it be possible to reproduce this today? Research revealed that power was supplied from a type of cell invented in 1836 by John Frederick Daniell, who gave it itsname.

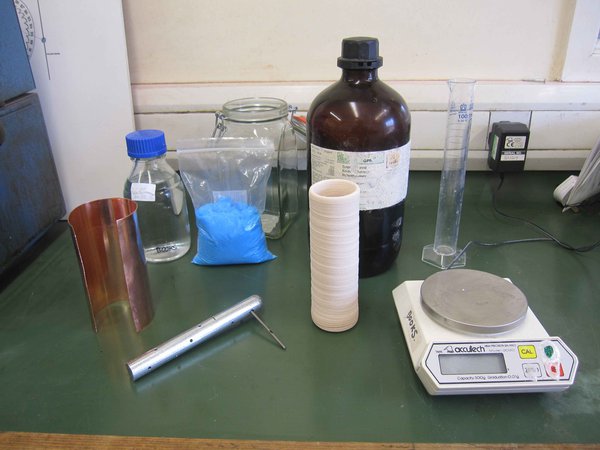

The next questions were: how was the Daniell cell constructed, would it produce a constant enough current for reliable operation of the clock and would the voltage be similar to a contemporary cell? With the support and collaboration of two other West Dean Clocks Programme students, Jonathan Butt and Kenneth Cobb, materials were gathered.

In order to re-create a Daniell cell, the following was needed:

- A porous vase (kindly provided by Alison Sandeman, West Dean pottery tutor).

- A zinc anode (as typically still used for boat protection).

- A copper pipe.

- Sulphuric acid solution.

- Copper sulphate.

- A glass Kilner jar.

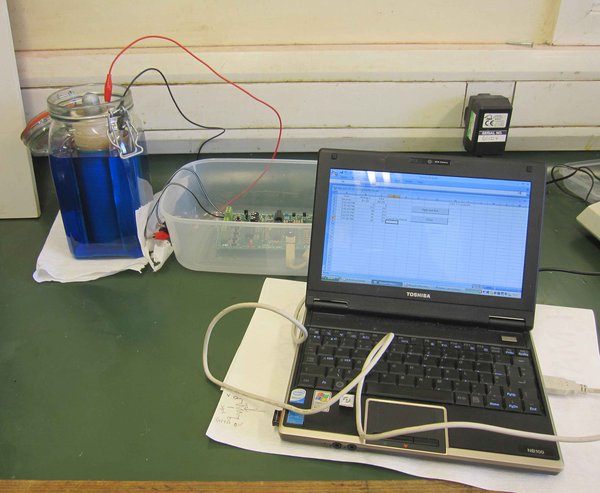

As soon as the sulphuric acid was added, the reaction started – the solution inside the vase started to fume and bubble and the cell produced current at its maximum voltage of about one volt. The cell worked constantly for five days (before the porous vase collapsed), with only minor intermittent drops in output (0.2 volts). During this time, the solution level within the vase dropped to almost half, copper crystals formed on the surface and thick crystals were visible at the bottom of the glass jar.

So we successfully made and tested a cell as it may have been made in 1836. Even with testing and research far from finished, it can already be said that:

- this clock was powered with a voltage even less than a modern 1.5 volt battery.

- it did not draw a huge amount of current from the cell, so the life length of the cell should have been of several days at least.

Furthermore, these results suggest that early electric clock systems were used in a different way from how we generally perceive them today.