The AHS Blog

Big Ben and the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

The iconic tower that houses the world’s most famous clock has always simply been known as the Clock Tower, but was renamed Elizabeth Tower to mark the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012. Will the name catch on? I think that the man in the street, and that includes the tourists, will continue to call it the Big Ben, even though that was never the name of the tower, just the nick-name of the hour bell.

On 10 June I attended the launch of a guidebook published by the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and the Elizabeth Tower. It was great fun because it was held in the Palace of Westminster, in the opulent State Rooms in Speaker’s House, which outsiders don’t often get to see. The book is attractively produced and richly illustrated, and those wanting more can read Chris McKay’s book Big Ben. The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster.

Mr Speaker, John Bercow MP, addressed the guests, after which there were short talks by Mike McCann, keeper of the Great Clock, and Paul Roberson, one of the three clockmakers responsible for winding, servicing and repair of over a thousand clocks in the Palace of Westminster.

Between them, they also have to provide a 365 days a year out of hours call-out service should the Great Clock have a problem.

This illustrated article by Chris McKay reports on an overhaul of the Great Clock, undertaken in 2007 to correct wear problems. Paul Roberson, who is currently chairman of the British Clock and Watchmakers Guild, ended his talk with a joke that is probably as old as the hills but was new to me: 'What did Big Ben say to the Tower of Pisa? "I’ve got the Time, if you’ve got the Inclination".'

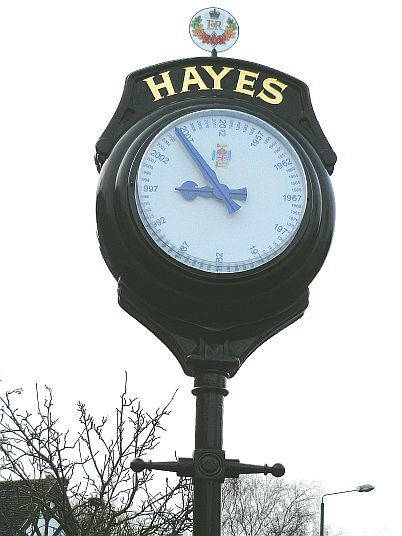

Elsewhere in the country the Diamond Jubilee has inspired modest horological activity. In February 2013 a jubilee clock was unveiled in Hayes in southeast London. The clock dial is made up of the sixty years of the Queen’s reign rather than minutes, with 2012 marking 12 o’clock.

And in Minehead on the Somerset coast they hope to build an 8.5 metre tower with a four-sided display, with clocks on three sides and current tide times on the fourth. They still need donations to make it happen.

There will have been more initiatives. But it was nothing compared to the public clock ‘mania’ that erupted on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, which I shall discuss in my next blog.

Navigating the trackless seas

This post was written by David Rooney

If you stand on the Thames riverside near the East India dock basin, the view south is extraordinary.

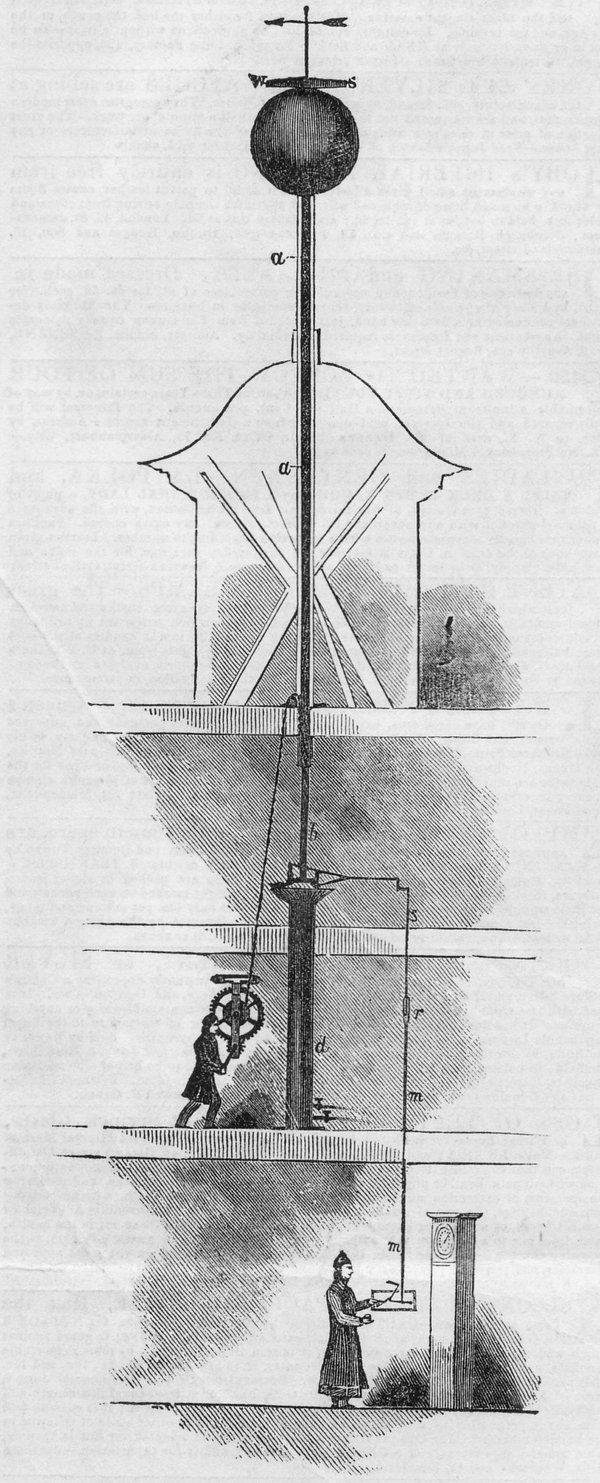

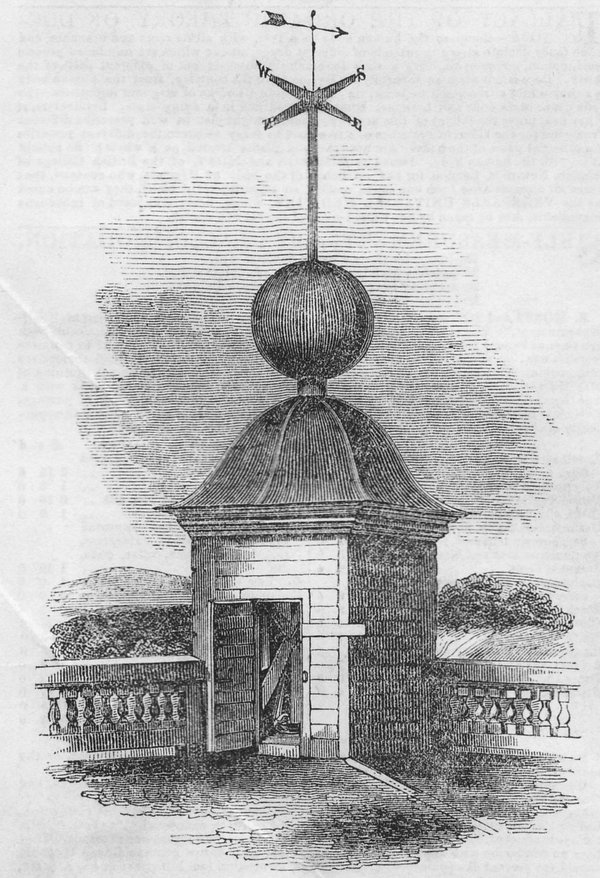

In the foreground is the remarkable structure of The O2, originally the Millennium Dome. But look further into the distance, and you’ll just make out the Royal Observatory perched atop the high reaches of Greenwich Park. Look even more closely and you will see the one of the world’s first public time signals fixed to its roof.

The Greenwich time ball has been a London landmark for 180 years, since it was first constructed in 1833. But it is more than just a tourist attraction. Until the early twentieth century it was a life-saving technological tour-de-force which enabled sailors leaving Britain’s busiest port to find Greenwich time to a fraction of a second – not for punctuality but for navigation.

Just over a decade after its erection, the Illustrated London News ran a major feature on this high-tech time-check.

'The keeping of true time is important to all persons', it observed, 'but to those engaged in navigating the "trackless seas", it is of such consequence, that the government … have not hesitated to expend large sums of money for its discovery, preservation, and announcement to the world.'

It is hard, today, to imagine this little cluster of modest brick buildings as a national centre for scientific excellence. But that is what it was.

As the newspaper explained, 'from the beauty of the instruments, the exactitude of the observations, and the high scientific ability of the officers engaged, the once difficult problem of finding the precise instant when one o’clock touches the world’s history, is no longer a matter of doubt or difficulty.'

We’ve developed other ways to know the time since 1833, but the ball still keeps dropping, and if you wait patiently on the riverside at East India with a pair of binoculars, you can still observe the precise instant of one o’clock every day.

Want to know more? Set your calendar for what promises to be a superb AHS London Lecture by Douglas Bateman on 19 September. See the website for details nearer the time.

‘I didn’t see him take anything, but they’re not here now’

This post was written by David Thompson

'Lost out of Mr. Garon’s shop on Monday the 14th instant, a gold watch, hook chain and seal all gold, on the dyal plate Garon London, one silver watch the name Garon London, another silver watch the name Clyet Landon: If the said watches be brought to be sold, pawn’d, valued or amended, you are desired to stop the goods and party, and send word to Mr. John Milburn a watchmaker in the Old Baily, and you shall have 6 guineas reward or proportionable for any part, or if brought to the said Mr. Milburn, the party shall receive 6 guineas, and shall have no questions asked'.

Politicus Mercurius, London, 17th-19th November 1709

Advertisements such as this are common in the London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne (1703-1714) and every one tells a tale. Just what happened here where Mr. Garon had three watches stolen from his shop we don’t know, but by any account the event was unfortunate.

Whilst this watch by Peter Garon is not the gold one described, there is no doubt, judging from this example, that a Garon watch was not something anyone would want to lose. The tortoise-shell (turtle) outer case inlaid with gold wire is a work of art in itself.

Peter Garon was a Huguenot who was formerly known as Pierre Garon and he had something of a chequered career. Brian Loomes in Early Clockmakers of Great Britain gives the following account.

Peter Garon was apprenticed to Richard Baker in April 1687 and finished his term in 1694. However, because he was still an alien, he was refused freedom by the Clockmakers’ Company but the Lord Mayor of London did grant that freedom in the same year. He became a Freeman in the Clockmakers’ Company in August 1694.

In October 1696 he admitted forging the name of a Mr. Legrand on a watch of his own making. In 1697 he was warned about taking unofficial apprentices and by 1709 he was clearly in trouble again.

'Whereas the acting Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt awarded against Peter Garon of London, watch-maker, have certified to the Right Honourable the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that the said. Peter Garon, both in all things conformed himself to the late Acts of Parliament made against Bankrupts: This is to give notice that his certificate will be confirmed as the said Acts direct, unless cause be shewn to the contrary on or before the 2d of March next.'

London Gazette 7th-10th February 1709

Note. We are hugely indebted to W.R. and V.B McCleod and John R. Milburn (no relation to the above) for their researches into the lost watch advertisements in London newspapers from the reign of Queen Anne.

Do clocks tick you off?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

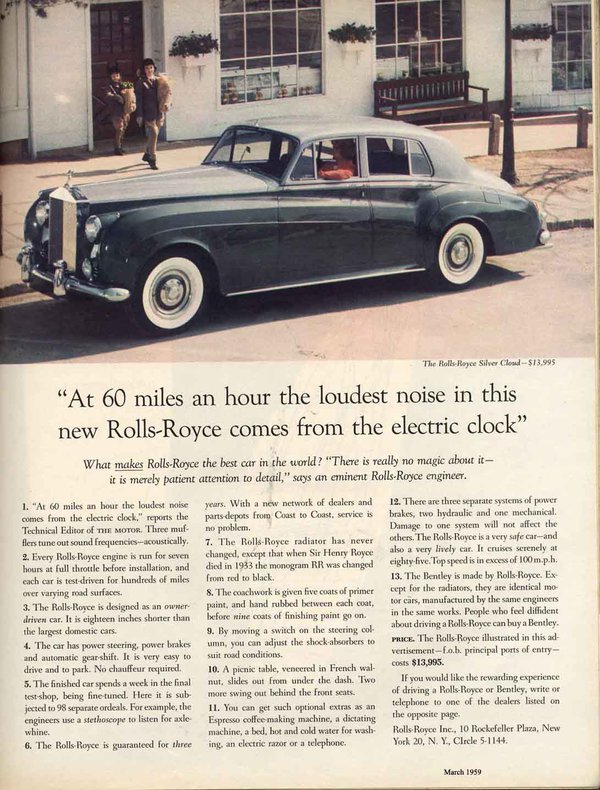

In his book Confessions of an Advertising Man, originally published in 1963, David Ogilvy calls this ‘the best headline I ever wrote'.

Interestingly, in a footnote he adds: 'When the chief engineer at the Rolls-Royce factory read this, he shook his head sadly and said “It’s time we did something about that damned clock!"'

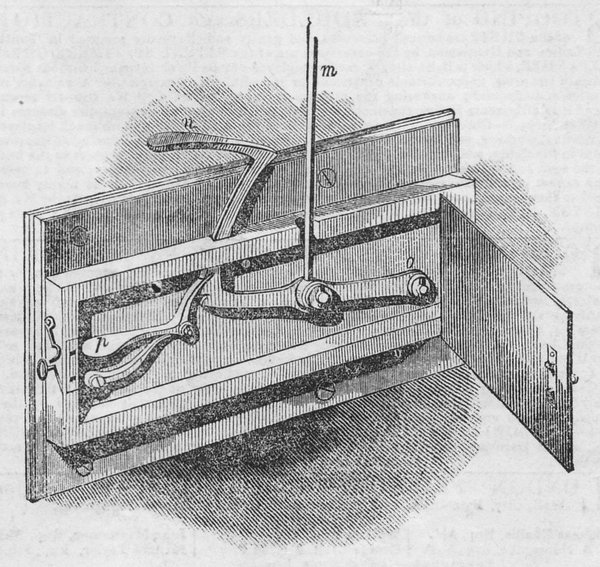

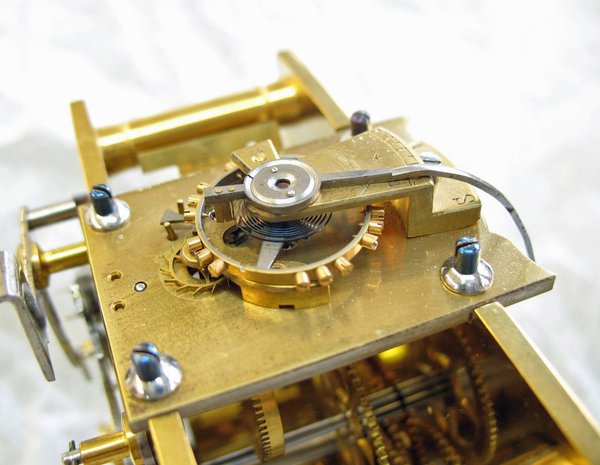

I previously explained that the ticking of a timekeeper is the sound of the escapement stopping a wheel tooth. But why is the ticking of a clock music to some and unbearable to others?

Loudness is a common complaint. The farther and harder the tooth drops before it is stopped by the escapement, the more energy is lost to sound and the louder it will be. This will tend to increase with size, but energy loss can be minimized with an efficient design and good construction. Also, the rest of the movement and its case can act to either attenuate or amplify the sound.

The timbre of the sound can be soothing or grating. Just like the character of a violin is much more than the pure tone of its vibrating string, we are not hearing just the escapement – the construction of movement and case all contribute to the texture of the sound.

Another aspect is the timing of the ticks – the beat of the clock. An uneven beat probably offends everybody. If, instead of an even 'tick tock tick tock tick tock', you hear 'ticktock… ticktock…. ticktock…' (or even tocktick!) then your clock is out of beat. To fix this, make sure the clock is level, otherwise your repairer can easily sort it.

Some examples:

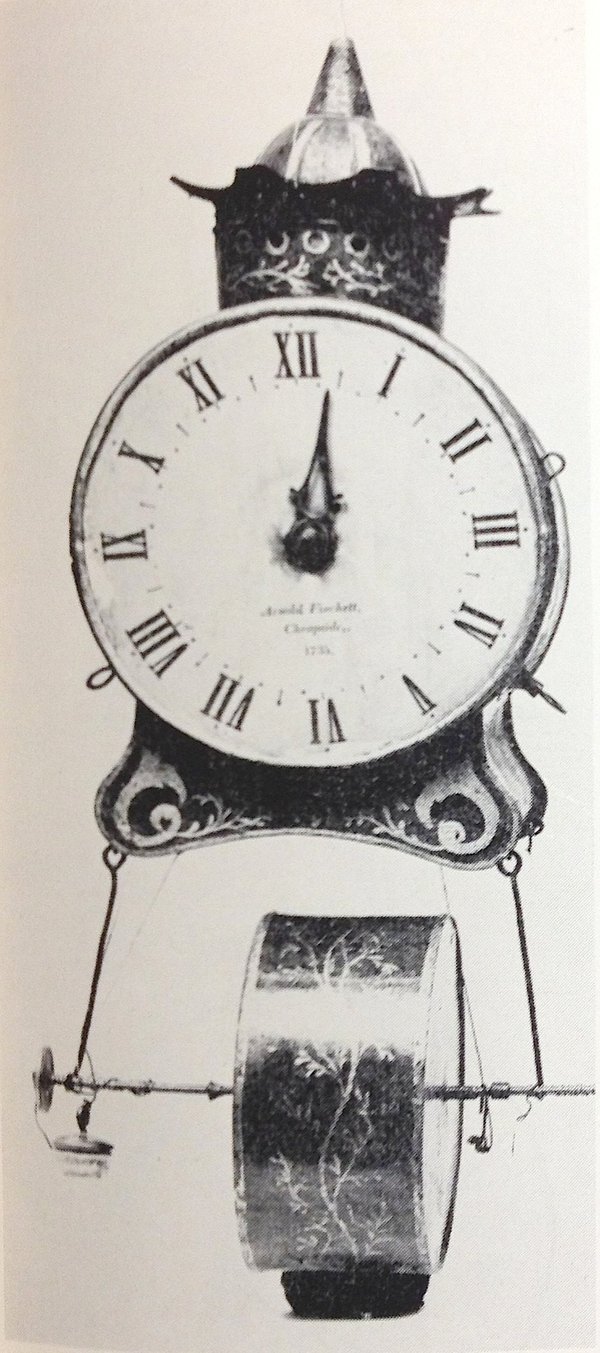

Some clocks were designed to reduce escapement noise. Some of these had so-called 'silent escapements' in which more compliant materials were used (such as spring steel and gut line) to absorb the impact. Pietro Tommasi Campani invented an impact-free crank escapement for use in his night clocks.

Avoiding escapements altogether, compartmented cylindrical clepsydrae were recurrently popular at various times in history. In quartz controlled clocks, the escapement is also eliminated, although many of those use physical hands whose driving motors can usually be heard, ticking or whirring.

Thanks to Peter de Clercq for inspiring this post and providing the piece on Ogilvy.