The AHS Blog

A second in one-hundred days: insanity or genius?

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

In 1775 John Harrison made a critical remark about Graham’s dead beat escapement, saying, of George Graham, that '…either he must be out of his Senses, or I must be so!'

Later in the same publication he stated of his own clock that '…there must be then more reason…that it shall perform to a second in 100 days…than that Mr Graham’s should perform to a second in 1.'

Keeping time consistently to within one second in 100 days was a degree of accuracy not achieved until around a century and a half later by mechanical clocks such as Shortt’s free pendulum system.

Harrison published his remarks in a vitriolic and virtually impenetrable book, the manuscript and transcriptions of which are freely accessible online.

On reading the book, which contains scattered descriptions of his method, the celebrated watchmaker Thomas Mudge, stated of Harrison that the book’s contents had '…lessened him very much in my esteem…' and that '…there are several things which he says about Mr Graham’s pallets and pendulum that are absolutely false…'.

The London Review of English and Foreign Literature described the work as 'one of the most unaccountable productions we ever met with' and went on to say that 'every page of this performance bears marks of incoherence and absurdity, little short of the symptoms of insanity'.

Harrison’s words were not taken seriously by any of his contemporaries and his radical statement about the capabilities of his pendulum clock, with its large pendulum arc, relatively light bob, and recoil grasshopper escapement, remained largely unexplored until the 20th century.

Then, in 1977, a number of horological scholars, who became known as The Harrison Research Group, began to look at his theories afresh.

Martin Burgess’ Clock B is a product of this collaborative research and represents one of the most significant historio-technical investigations in recent years. Recently, numerous experiments have been tried on the clock at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich with exciting results.

To learn more about this intriguing project please join us for a special one-day conference on July 12 2014 at the NMM.

The AHS Annual Meeting 2014

This post was written by David Rooney

On Saturday 17 May, 120 AHS members and guests packed into the National Maritime Museum’s lecture theatre for our 2014 Annual Meeting. It was a sell-out crowd, and what a day we all enjoyed.

Those who couldn’t make it missed a couple of important announcements which I’ll pass on here in advance of them appearing in the next Antiquarian Horology .

The first announcement came from Sir Arnold Wolfendale, the 14th Astronomer Royal, who has been a tireless supporter and champion of the AHS since becoming our President over 20 years ago.

Sir Arnold, whose inspiring and lively lectures on cosmological aspects of timekeeping have been enjoyed by so many of us over the years, has decided to stand down. We wish to thank him hugely for all of his support over the years and wish him well in his ‘retirement’ from the presidency.

David Thompson then announced that Professor Lisa Jardine, the eminent historian, writer and broadcaster, has agreed to become our new President, and takes over immediately.

Lisa is teaching this term at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena (home of the recent Time For Everyone symposium), and could not be present in person, but she sent her best wishes and looks forward to meeting us in person in the near future.

We are delighted and honoured to welcome Lisa to the AHS presidency.

The other major announcement of the day was the launch of the brand new AHS website. We urge you to take a look. It is the culmination of many months of patient work by a small AHS team plus our designers, Latitude, and our web developers, Blanc, and has been fully funded by a donation from council member James Nye.

At the heart of the website is a remarkable new resource for AHS members. We have digitized the entire back catalogue of Antiquarian Horology, and every single page we have ever published, dating back to the first issue in 1953, is now available and searchable online.

We are thrilled to bring this invaluable resource to members and wish to thank our great friends and technology partners, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in Germany, for carrying out the scanning and indexing work at an extremely preferential rate.

You can find the new website at our usual address, www.ahsoc.org, and to use the digital journal, simply log in to the members pages with the password printed on the back of your AHS membership card.

The addition of the journal archive is an extremely valuable new member benefit which must surely be worth the AHS subscription alone, so do please encourage your friends, colleagues and clients to join (don’t forget that you can join online using credit cards, debit cards or PayPal in just a few easy and secure clicks).

A tiny housekeeping note. The AHS blog on which you are reading this post has now moved to blog.ahsoc.org. The old address will still work fine, but if you subscribed to posts using an RSS feeder, we’re afraid you’ll need to re-subscribe from the new location. Sorry about that.

There’s never been a better time for reform!

This post was written by James Nye

A gauntlet has been laid down. Across Europe, thoughtful people are busy working up ingenious ideas for a competition devised over an extraordinary April weekend in southern Germany.

Each year, several dozen of the electro-horo-cognoscenti gather in Mannheim-Seckenheim for an event organised by Till Lottermann and Dr Thomas Schraven.

The fifteenth of these gatherings—a combination of market, lectures and much eating, drinking and good conversation—saw a new visitor who brought many interesting items, not least several hundred new-old-stock Reform movements, tissue-wrapped and boxed.

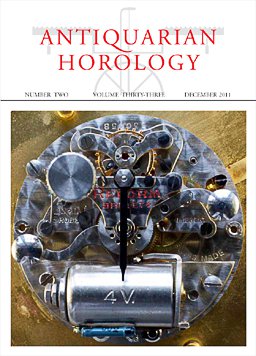

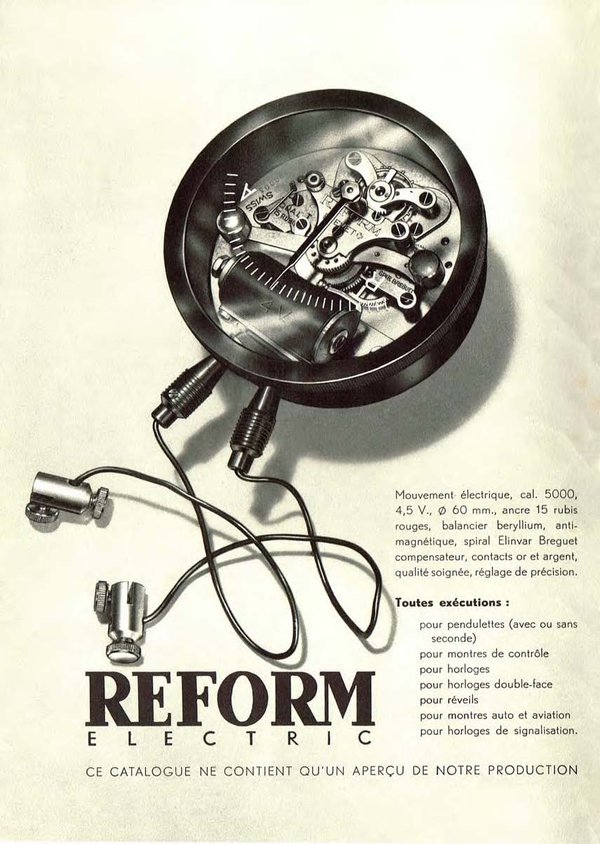

Alert readers will recall an Antiquarian Horology cover featuring a classic example of the Reform calibre 5000 movement, and a fascinating accompanying article.

As David Read comments, these Schild movements are ‘without doubt the best known and most commercially successful of all the many varieties of electrically-rewound clock movements’ from the 1920s onwards. The calibre 5000 is a lovely object, jewelled, with damascened plates, and micrometer regulation.

Nye’s theorem proposes that hi=as*bc/ebw where hi stands for horological inventiveness, as represents afternoon hours of sunshine, bc denotes beers consumed and ebw stands for evening bottles of wine.

With a lively group, talk over two sunny days and late evenings turned to possible creative uses for virgin Reform movements.

Given their looks, the mechanism must remain visible, but the motion work is to the (unremarkable) reverse. This led to discussions of projection clocks, or elaborate gearing to present time in the same plane as the movement, but to one side.

There was even intriguing talk of a large scale tourbillon. More detail than this presently remains closely held, but a competition to determine the best use was announced, to be decided in Mannheim in April 2015.

Reform is the order of the day.

Of mice and clocks

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In his most recent blog, Oliver Cooke discussed watches and clocks without hands as indicators.

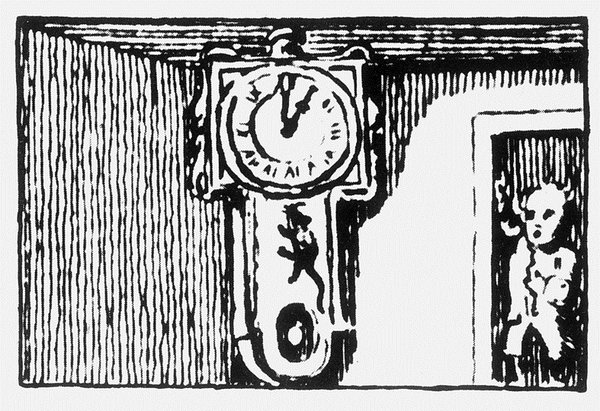

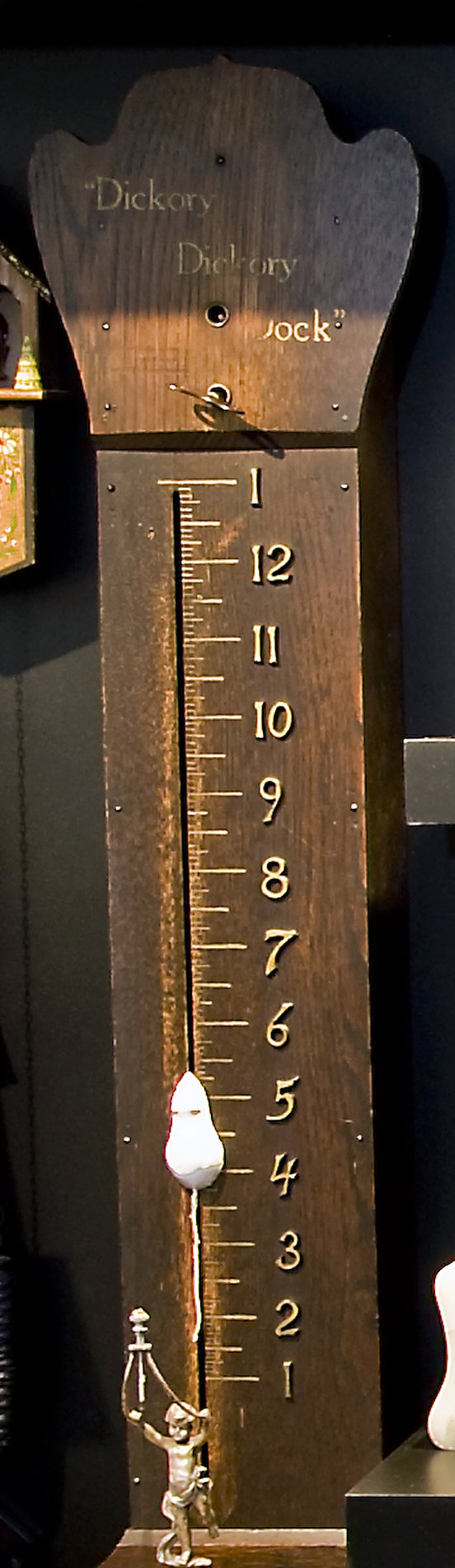

Another example is the Mouse Clock, in which a mouse making its way up against a wooden board serves as time indicator. Its designer was inspired by the well-known nursery rhyme:

Hickere, Dickere Dock

A Mouse ran up the Clock,

The Clock Struck One,

The Mouse fell down,

And Hickere Dickere Dock.

The rhyme comes in various versions; this is the oldest, published in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s_Pretty_Song_Book.

Could it be based on a real event: a mouse hiding inside a longcase clock, panicking when it struck?

In the literature I find only other explanations. One authority suggests it may be an onomatoplasm – an attempt to capture, in words, a sound; in this case, the sound of a ticking clock. Another relates it to the shepherds of Westmorland who once used ‘Hevera’ for ‘eight’, ‘Devera’ for ‘nine’ and ‘Dick’ for ‘ten’ when counting their flock.

Be that as it may, just over a century ago it inspired an American businessman, who was also an avid clock collector, named Elmer Ellsworth Dungan, to develop the Mouse Clock.

He initially just created one for his daughter, who loved the nursery rhyme, but then decided to take them into production. He took out patents and various models were manufactured.

They are nowadays prized by novelty clock collectors, so much so that we are warned to beware of reproductions, especially for what one dealer calls ‘Chinese knockoffs’.

Details, including several images of the mechanism, and a link to an animated photo of the clock in operation, can be found on these American websites: Antique Clock Guy and Fontaine’s Auction Gallery.

In 1966 the NAWCC published a booklet by Charles Terwilliger, Elmer Ellsworth Dungan and the Dickory, Dickory Dock Clock; there is a copy in the AHS Library at the Guildhall.

And speaking of mice and clocks, how about having some fun with the (grand)children with this on-line clock reading game. Read the time correctly and the mouse runs up safely to the cheese in the clock. Read it wrong and the cat gets the mouse.

British Pathé films on YouTube

This post was written by David Rooney

In the latest in what seems to have become a short series on easy-access digital resources, I bring news that British Pathé has released its entire historical newsreel archive of 85,000 films onto YouTube, the video-sharing website.

British Pathé has long allowed people to see its historical newsreel films on its own website, and the release to YouTube doesn’t bring any change to the company’s copyright policy. But the findability of these often remarkable films will now have greatly increased, which can only be a good thing.

I have used British Pathé films in my historical research and my professional work curating museum exhibitions for years now, and it is therefore like meeting old friends to watch films on the YouTube channel such as The Golden Voice, Time Please and Standard Time.

For those with wider interests, I’ve also been moved seeing Comet Inquiry again, which appeared in the Science Museum’s recent award-winning Alan Turing exhibition. One of the AHS’s founder members, Alfred Basil Brooks, together with his wife, were killed in this tragic air crash which occurred just months after the founding of the society.

I think this film archive is strong in two ways beyond its sheer breadth.

Firstly, it helps to put technological objects and ideas into social and political context, which is crucial in understanding why people make, modify, use and choose things. Objects never emerge fully-formed in a contextual vacuum.

The second strength of the films is the technical understanding they can offer those studying particular technologies. There’s nothing like the moving image to bring dynamic objects to life.

So there we are. Another great digital archive of work made even easier to use. And along those lines, AHS members should watch out for an important announcement in the next few weeks. We’ve been working on something pretty special and we’re about to be able to share it with you…

You can find the British Pathé channel at https://www.youtube.com/user/britishpathe. Search by clicking the little magnifying glass symbol in the middle of the page underneath the header image.

Time in Old Bohemia

This post was written by David Thompson

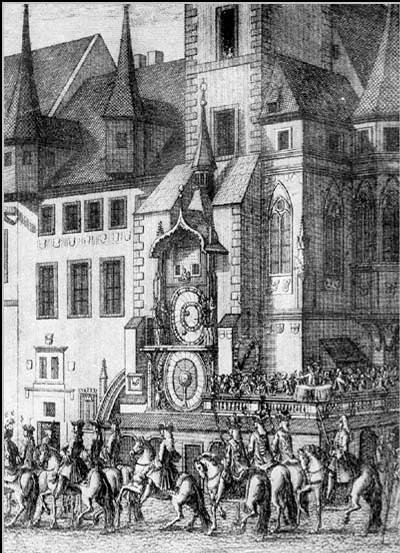

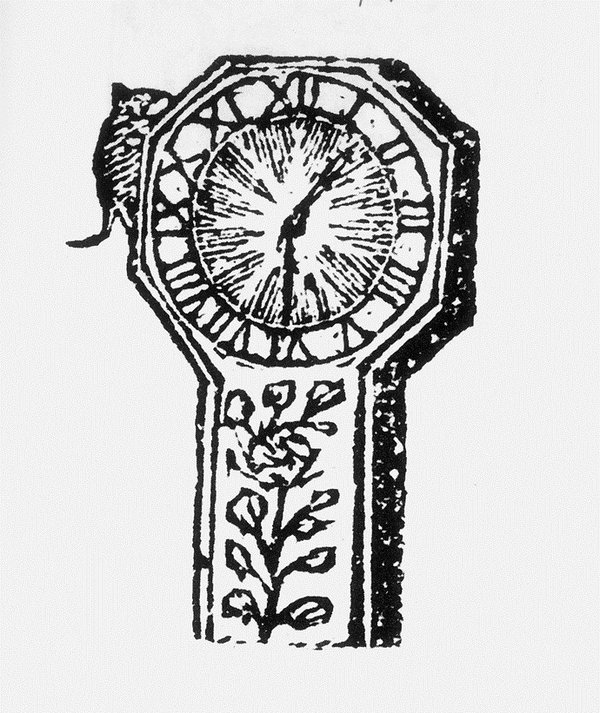

Many thousands of people today have stood amazed in front of the Astronomical Clock in the Old Town Hall Square in Prague, but I wonder just how many have managed to make sense of the dial. In modern times, perhaps it makes little sense.

The clock was made by Jan Šindel in about 1410, and from as early as the 15th century, the clock had a 24 hour dial which showed the so-called Bohemian Hours, a system in which the day began and ended at sunset.

This means, of course, that the 24-hour ring around the outside had to be adjusted periodically so that the 24th hour coincided with sunset.

In the early part of the clock’s life this was done manually, but later an automatic mechanism was installed to adjust the position of the ring. In medieval Prague, a knowledge of how long it was to sunset and the imposition of curfews in the city was useful knowledge. For instance – a simple glance at the dial indicating 19 hours tells you straight away that it is five hours to go before sunset.

As well as telling the time, the dial also has moving sun and moving effigies of the sun and moon, showing where in the zodiac they lie throughout the year. Useful astrological information.

The ecliptic circle with the zodiac signs and the sun and moon effigies rotate together once per day, but gradually over the course of the year, the sun and moon effigies with make a complete circle of the zodiac.

All this is achieved by some sophisticated gearing located behind the dial and driven by the clock mechanism in the tower. With the horizon circle with shaded buff areas, the periods of Aurora and Crepuscular, dawn and dusk are also shown,

Today, the clock is controlled by a more modern ‘regulator clock made by Romuald Bozek in the 1860s, but for the most part, the clock mechanism is still that which has been in existence from the beginning of its history.

Looking at the illustration here, you will see that the time is just a few minutes past 13 hours. On the fixed chapter circle the time is shown just before IX o’clock in the morning and hour 24 is just before 8 o’clock in the evening – correct for a July date. The sun is in Leo and the moon is in Aries.

So next time you stand in front of this amazing clock, you can really show off by knowing how to read the dial.