The AHS Blog

Lighting up time

This post was written by David Thompson

The story of the night clock, a device which allows the time to be seen in the dark is a long one.

In this modern era of instant electric light, it is easy to forget that in earlier times, getting light at night was quite an involved business. So what better way to solve the problem than to have a clock which was illuminated all through the hours of darkness.

One of the earliest examples of these clocks was that invented by the Campani brothers, Giuseppe, Pietro Tomasso and Matteo Campani from San Felice in Umbria, who worked in Rome in the second half of the 17th century.

However, one clock which caught my attention was a much later, metal cased clock in the form of a Greek urn in which was placed a light source –oil lamp or candle, and which had a system of lenses to project an image of the dial onto a wall in the room.

The clock was made and retailed by the inventor and optical instrument maker Karl August Schmalkalder, born on 29th March 1781, in Stuttgart, Germany. He came to England in about 1800 where he anglicised his name and in later years worked in partnership with his son John Thomas Schmalcalder. On his retirement in 1839 the business was continued by his son.

Charles Augustus married Charlotte Ann Cochran on May 24, 1804, in St Andrews church, Holborn and he died on December 25, 1843 in the Strand Union Workhouse – although he is renowned for his patented prismatic compass, a mechanical drawing device, optical instruments and barometers, sadly his genius did not make him a rich man.

Whilst the Schmalcalder name appears on the clock dial where he describes himself as ‘Patentee’. I have failed to find a patent in that name for this device – it may be that he is simply telling his customers that he is a holder of patents not specifically for this illuminating device.

For a detailed account of the Schmalcalders, although without detail of this clock see – Julian Smith, ‘The Schmalcalders of London and the Priddis Dial’, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Volume 87, No.1, 1993, pp. 4-13.

For more information on the Charles Augustus Schmalcalder, see the family history website created by Steve Smallcalder.

Friends reunited?

This post was written by Matthew Read

Revisiting the Bowes Swan this week – the first time since it was completely disassembled in 2008 – was a personal and surprisingly profound experience.

There is a blogged account of the 2008 conservation project on the web site of the Bowes Museum. That project was at least from my perspective, a commercial professional endeavour, and very hard work!

As the intervening years have passed, some of that professional objectivity has slipped and allowed the Swan and the wonderful Bowes museum to become part of me. Yes, and of course, one can dine out on a project like that for a very long time indeed.

However, snapping back to hard reality, the swan is a bunch of clockwork, levers, cams and ingenuity, and the purpose of this recent visit was to see how everything has stood up to nearly four years of use.

The automaton being played once a day every day the museum is open to the public. Well, of course, as would be expected, it’s a mixed bag. Heavily loaded bearings and working surfaces take the brunt, some mid-twentieth century restorations do not fit quite so comfortably with the eighteenth century, yet overall, the policy of maintenance, observation and importantly, engagement by staff at the museum, seems to be striking that very fine balance between cost (in the widest sense)and benefit.

So the show goes on, the public watch, children stare, almost everyone films and photographs, and often the daily performance receives a round of applause. If you haven’t already, you really should see the sensual and magical swan in action. The Swan is operated daily at 2.00 pm.

Waking up with a bang

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

In my own time I am Adviser to the National Trust on the care and curatorship of their clocks and watches, and occasionally the Trust’s Advisers on different disciplines are called upon to work together.

Clocks and Firearms might seem an improbable combination, but one object in the Trust’s collections recently brought me and Brian Godwin (Adviser on Firearms) together for a most interesting study day.

Snowshill Manor, a house full of surprises, was, almost inevitably, the source of the object in question – a little gilt-brass table clock with alarm, made about 1740 and signed by Peter Mornier, London. The Trust has any number of clocks with alarm mechanisms, but this particular example has an additional feature, guaranteed to have the owner out of the deepest slumber in a trice.

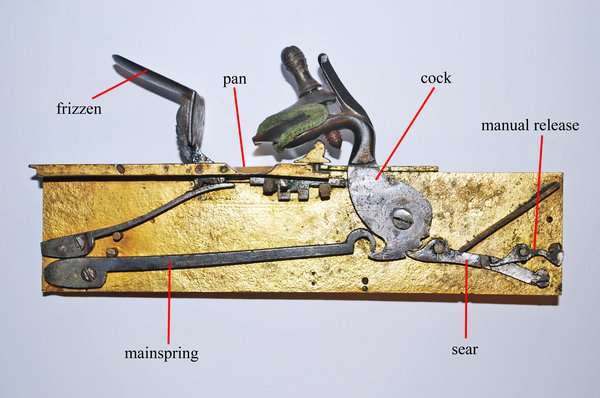

As with most alarm clocks of the period, the clock sounds a bell at the appointed hour, but then, a flintlock mechanism is triggered and, with a flash and a bang, a lighted candle swings up from a compartment within, jack-in-a-box style, and illuminates the bedside. In fact, if the candle isn’t securely fixed in its swivelling socket inside the clock, there is a distinct possibility it is projected onto the bed itself, guaranteed to have the occupant up and about.

The mission of the two Advisers included a desire to see – and film – the clock working, if at all possible. Needless to say, careful preparation was required to ensure the clock itself was safe and the test was carried out in a brick-lined vault at the back of the Manor, although only a tiny quantity of black powder is needed to fuel the flintlock.

In the event however, not a single ignition took place, as the flintlock’s frizzen (the hardened steel plate against which the flint is supposed to strike the sparks) appeared to be too worn already, and would not oblige. It seems the clock has done its fair share of early morning duties over the years and is entitled to take an extended rest.

A few more experiments will take place to see if we can’t persuade it to perform just once more for the cameras; meanwhile further research on the clock, on Mornier, and on other examples of this kind, is underway and will be written up in Antiquarian Horology in due course.

A la recherche du temps synchronisée

This post was written by James Nye

A number of us are fascinated by the whole concept and practice of synchronized public time. As well looking at the time transmission systems installed in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin and elsewhere in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, there are other intriguing facets to the world of time, its accuracy and its perception.

On something of an exotic riff, consider time in art. Dalí played with relativity in The Persistence of Memory and its softening watches, whilst Proust’s masterwork meticulously articulates the recovery through memory of a life observed at obsessively close detail – one can feel the clock ticking the author’s life away second by second as the narrative unfolds.

Back to the main hook, and significantly more prosaic, the clock, or broken watch, features regularly in detective fiction – think of Agatha Christie’s Clocks . Alibis often depend on time. I’ve collected detective fiction all my life, and recall the pleasure at finding Lord Peter Wimsey occupied a world full of synchronized clocks.

Witness the following from one of Dorothy L. Sayers’ finest books, Murder Must Advertise:

'The tea-party dwindled to its hour’s end, when Mr Pym, glancing at the Greenwich- controlled electric clock-face on the wall, bustled to the door, casting vague smiles at all and sundry as he went.'

Later in the same book, we learn of Wimsey’s difficulties at remaining in character, in disguise in an advertising agency… 'Nor, when the Greenwich-driven clocks had jerked on to half-past five, had he any world of reality to which to return…'

Sayers again touched on a number of public time themes in a later Wimsey story, Have His Carcase:

'In that intriguing mystery, the villain was at that moment committing a crime in Edinburgh, while constructing an ingenious alibi involving a steam-yacht, a wireless signal , five clocks and the change from summer to winter time.'

I’ll close with an appeal. If you know of similar appearances of time-signals, synchronized clocks and the like, in plays, novels, whatever, I’d love to hear about them!