The AHS Blog

Wristwatch Group meeting, 14th January: conservation and restoration

This post was written by Mat Craddock

In the gas-fired warmth of the Royal Arcade, WWG members heard Justin Koullapis (our gracious host, The Watch Club), Adam Phillips (casemaker and restorer), Greg Dowling (WWG member and watch collector) and Oliver Cooke (Curator, Horological Collections at the British Museum) discuss originality in watches.

Oli’s curatorial view of conservation was, perhaps, the most extreme: once an item enters a collection, the aim is to put it into stasis, free from the damaging effects of winding or lubrication.

From a collector’s point of view, Greg said that the possibility of wearing and using a watch might lead him to seek out to the most appropriate way to restore the piece to working order.

Adam agreed, and seemed largely happy to undertake work under the direction of his customers, taking the view that sensitive restoration and repair can extend the useful life of a watch.

Justin’s thoughts on the subject were from two, contrasting, points of view: as a non-practising watchmaker and as a watch dealer. He said that great value is placed on entirely original objects, many of which have been hidden away for many year. However, his fascination with how objects were made often caused him to place more value on the skills of the watchmaker, rather than the watch itself.

Questions were taken from the audience, and covered topics such as dealer versus collector (the panel was split on the definition of a collection); the dangers of old radium (the British Museum has their luminous watches stored in steel-lined rooms that are externally force vented); and even the purpose of collecting watches.

In response to the last question, Mr Dowling quoted from the late Dr George Daniels: there’s nothing more attractive than a good watch. It’s historic, intellectual, technical, aesthetic, amusing, useful.

A fitting end to an interesting evening.

The annual winding of the Mostyn Tompion

This post was written by James Nye

28 January 2016. To the British Museum, at the delightful invitation of the horology curators to take part in a little-known and wonderful ceremony – the just-once-a-year winding of the glorious Mostyn Tompion.

The Deputy Director, Jonathan Williams, offered a warm welcome, amply elaborated by Paul Buck, senior horological curator, who walked us around the origins and detail of this extraordinary object.

It runs for a whole year on one wind, striking every hour of that year (56,940 blows). The clock case, a confection of ebony veneer, silver and gilded brass, is rich in symbolism, covered in the heraldry and armorial paraphernalia of England and Scotland, richly intertwined – an interesting hint to the politicians who only wind each other up on such matters.

Made for King William III by perhaps our most celebrated maker – Thomas Tompion ( Westminster Abbey-buried, no less) – the clock descended on the royal death through various titled families before settling with the family of the early Lords Mostyn, finally landing in Great Russell Street in 1982.

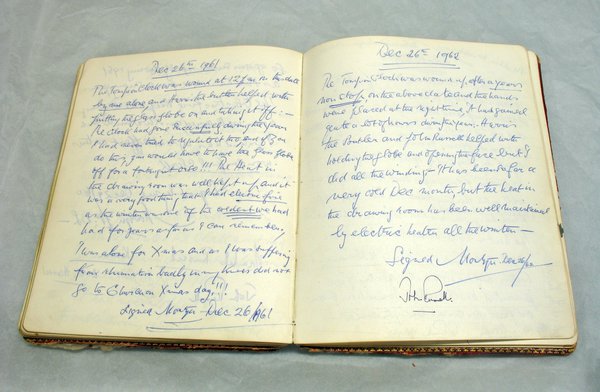

From c.1793, the Lords Mostyn held a small party to mark the annual winding of the clock, with each winder entering their name in a book. This tradition has been kept firmly alive at the British Museum.

The old family record was open for us to see, turned to the page for 26 December 1961, when Lord Mostyn recorded being on his own for Christmas, and winding the clock, which had ‘gone successfully during the year’.

Amusingly his idea of being on his own did not allow for the presence of the butler, who helped replace the dome over the clock.

These were memorable times – Mostyn, much troubled by rheumatism, also recorded ‘The heat in the drawing room was well kept up, and it was a very good thing that I had electric fire as the winter was of the coldest we had had for years’.

Winter, spring, summer and fall continue to unfold, watched over from Gallery 39 by a remarkable clock, which draws breath just once in each cycle of seasons.