The AHS Blog

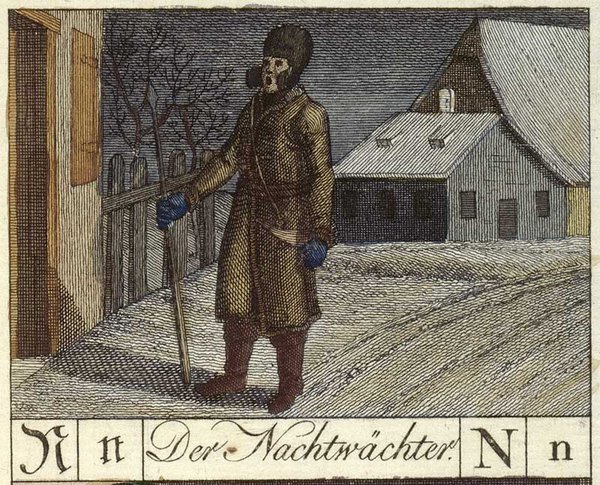

Night watchmen

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Richard Wagner set his glorious opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-singers of Nuremberg) in that German city in the sixteenth century.

In the second act a night watchman sings (the English translation in the vocal score is somewhat awkward as it aims to preserve both metre and rhyme):

'Hark to what I say, good people;

strikes ten from every steeple;

put out your fire and eke your light,

that none may take harm this night.

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat zehn geschlagen;

bewahrt das Feuer und auch das Licht,

dass Niemand Schad‘ geschicht.

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

The act concludes with his re-appearance:

'Hark to what I say, good people;

eleven strikes from each steeple;

defend you from spectre and sprite;

let no power ill your souls of fright!

Praise the Lord of Heav’n'

[Hört, ihr Leut’, und lasst euch sagen,

die Glock‘ hat elfe geschlagen;

bewahrt euch vor Gespenster und spuck,

dass kein böser Geist eu’r Seel‘ beruck‘!

Lobet Gott den Herrn].

From the middle ages until late into the nineteenth century, the night watchman patrolling the streets at night, calling the time and keeping an eye out for any kind of mischief or irregularities, were a common figure in many towns and cities.

Although he set his opera in the sixteenth century, watchmen were probably still active in Nuremberg when Wagner wrote his opera in the 1860s.

One century earlier, an Englishman visiting Nuremberg recorded in his travel journal 'Every evening about nine o’clock a fellow goes up and down the streets singing, and gives notice of the time of night, and bids people put out their candles. About the same time and at three in the morning trumpets are sounded.' (Sir Philip Skippon, An Account of a Journey Made Thro’ Part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy and France , 1752).

In her book The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London , Judith Flanders writes that for a small fee, a watchman might act as a mobile alarm clock, stopping at houses along his route, to waken anyone who needed to be up at a specific time.

The patrols of the night watchmen were not an undivided pleasure.

In his classic tale Humphrey Clinker (1771), Tobias Smollett has a long-suffering character say, 'I start every hour from my sleep, at the horrid noise of the watchmen bawling the hour through every street, and thundering at every door; a set of useless fellows, who serve no other purpose but that of disturbing the repose of the inhabitants.'

Acknowledgment. It was Wagner’s opera that made me want to know more about these night watch men, and I found much information in this article: Philip McCouat, ‘Watchmen, goldfinders and the plague bearers of the night’, Journal of Art in Society (2014), www.artinsociety.com.

Clockpera at the British Museum

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

The pairing of clocks and opera has been a recurring theme in this blog (1, 2, 3) and I am now happy to report on another such coincidence.

Over recent years, members of an opera production company, Brolly Productions, have made several visits to horological study room at the British Museum (where I work).

They came to look at different kinds of clocks and understand how they work, in order to provide a solid foundation for the design of their latest production, “CLOCKS 1888: The greener”.

The lead character is a 'greener', i.e. 'an immigrant who has only recently arrived', who were common to East London in the 19th century in which the opera is set.

She is responsible for maintaining the clock that controls the workforce of the East End but she comes under pressure from her overseer to alter its running to increase production.

Also, 'of course it is an opera, so there has to be a love story' says Dominic Hingorani, Librettist & Director of Brolly Productions.

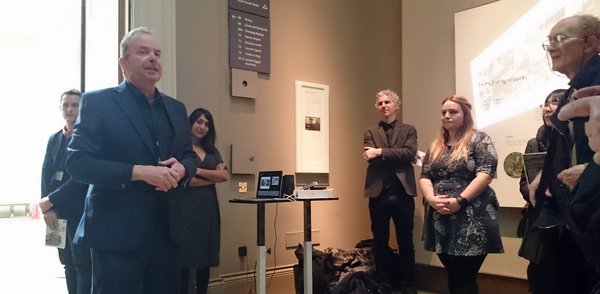

Last Friday lunchtime, in the horological gallery of the BM, an event was held to celebrate the collaboration.

The highlight of this were two songs from the production, performed by Keisha Atwell, who plays Greener. Freddie Matthews, Head of Adult Programmes of the BM, introduced the event.

Dominic then spoke about the evolution of the production. Rachana Jadav, Designer & Illustrator of Brolly Productions, spoke of the creation of the design, including the influence of the BM clocks.

Also speaking was Paul Buck, Curator of Horology of the BM, who told how the horological team embraces access to the collection and will consider even the most diverse requests. Indeed, access to the collection is available to all students, not only horologists.

Members of the AHS have the opportunity to visit the horological study room for talks from the curators and close-up viewing of objects. These group visits are organized by the AHS’s regional sections.

CLOCKS 1888: The greener is playing at CAST Doncaster, Fri 15th April to Sat 16th April 2016 and at the Hackney Empire, Wed 20th April to Fri 22nd April 2016.