The AHS Blog

What on earth?

This post was written by James Nye

In a few days, Francoise Collanges will embark on a project involving the Alexander Bain clock at The Clockworks. We will survey the clock, compare it with examples at the Science Museum, the Guildhall and Greenwich, and work out how to operate it safely over the long-term.

Someone asked if we intend to drive it with an earth battery (the way Bain did), and this reminded me of an experiment, back in the 1990s.

What’s an earth battery, you may ask? Remember the ‘potato clock’, where the power for a small battery clock comes instead from a galvanised nail and copper wire inserted into a potato? The potato provides the ‘electrolyte’ between the two metals – it’s the water in the potato really – allowing electrons to pass from the zinc to the copper, providing Volts.

In an earth battery, the moist soil beneath the surface allows the same thing. The battery is ‘used up’ as the zinc disappears.

Elements can be ranked ‘galvanically’ – indicating the volts you can achieve from a combination. Magnesium/copper gives 1.45V, zinc/copper (potato clock) 0.9V. But Bain buried zinc plates and a lump of retort coke (carbon), producing 1.1V, enough for his sensitive clock.

In Leicester, an earth battery apparently powered a clock for about fifty years, and we set out to beat this run – calculating the zinc needed, given the rate at which it would be consumed – 2,671 grams in our case. Two specialist firms produced the carbon and zinc electrodes to our design.

I buried them a metre down and ran a clock for several months. But the battery stopped working. A post mortem suggests a flaw in our zinc block – it should probably have been a large thin plate – with maximum surface area. The thousands of surface flaws in Bain’s retort coke were actually an advantage. We could give it another go at The Clockworks – trouble is, we sit on concrete, so we’ll need to ask the neighbours if we can bury electrodes in their garden!

Sundials can be sobering and noisy

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

Whereas a clock or a watch tells us at a glance what time it is, finding the time with a sundial is less easy. And it only works when the sun shines. Serious limitations, one might argue.

But this does not make them less attractive or fascinating. Indeed, there are societies entirely devoted to the subject, such as the British Sundial Society (BSS) whose members study and record old sundials and enjoy designing and discussing new ones.

Sundials come in many sorts. Like clocks and watches, they range from pocket-sized (Figure 1) to monumental (Figure 2), and from straightforward to mind-bendingly complicated.

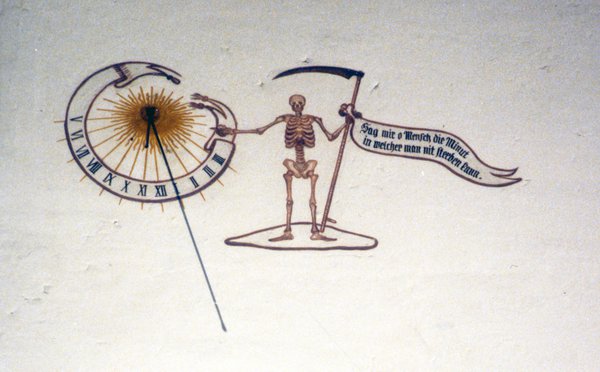

What I like about them is that they can come with arresting imagery and texts. An example is the sobering memento mori we saw years ago on an Austrian church (Fig 3). The Grim Reaper would fit perfectly in the exhibition Death: A Self-Portrait, currently at the Wellcome Gallery in London.

Sundials are quiet. Not for them the reassuring tick-tack of a clock, or the quarterly or hourly chimes.

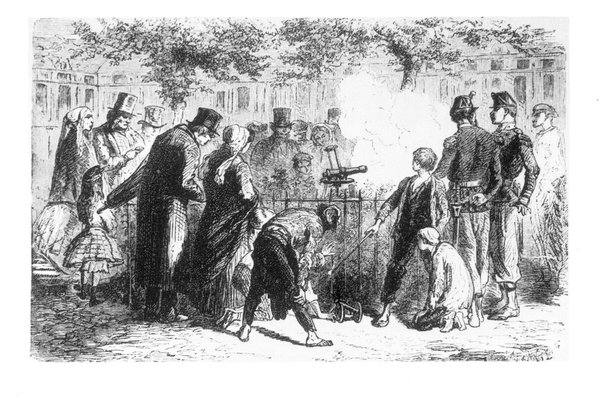

But there is one exception: the cannon dial, also known as solar cannon or noon cannon (Fig 4). It is fitted with a burning lens, so arranged that the Sun’s rays are directed to the touch hole of a small cannon. At noon precisely, it goes off with a bang! People could set their watches by it (Figs 5 and 6).

It was an acoustic variant of the Greenwich time ball, which for generations has been dropped every day at 1 pm sharp – initially for ships’ navigators to check their chronometers, and now purely as an enjoyable public spectacle.

Seventy-Seven Clocks

This post was written by David Rooney

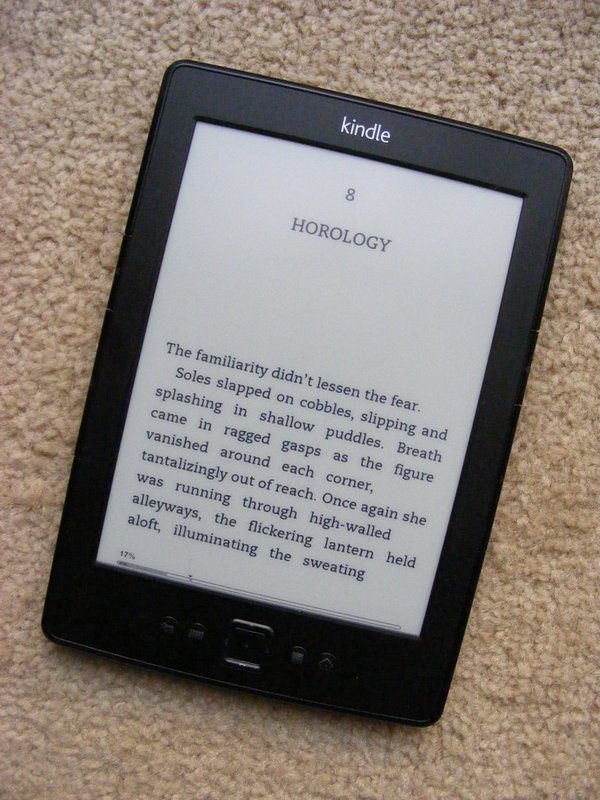

One of the security officers where I work stopped me a few weeks ago. He was reading a crime fiction novel and thought I might be interested. It’s called ‘Seventy-Seven Clocks’. You can perhaps see why he thought of me.

During these long January evenings, many of us find time to catch up on our reading – and there’s a lot to catch up on.

I am sure you are already onto your second reading of Bob Miles’s superb masterwork on the Synchronome company, published by the AHS last year. And if you haven’t yet seen a copy of Ian White’s exploration of English clocks for the Eastern markets, the AHS’s latest book, then there’s a treat in store for you.

But having devoured those two books, you might want something a little lighter, and for that, I can recommend Christopher Fowler’s Seventy-Seven Clocks.

With chapter titles such as ‘Horology’, ‘Clockwork’, ‘Automaton’ and ‘Mechanism’, it’s shot through with mechanical ingenuity. (There’s also ‘Vandalism’, ‘Detonation’, ‘Darkness Descending’ and ‘Glorious Sacrifice’, so it’s not for the faint-hearted.)

I don’t want to spoil the plot, but suffice to say anyone who’s a member of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, or who collects clocks and watches, or who has ever been involved in running a business might well be absorbed by Fowler’s fictional tale.

It’s beautifully detailed, acutely observed, and full of horology – although I never imagined it could be so wicked ! I’ve since read other titles in Fowler’s series and they’re great. One mentioned the sundial-fountain in St Pancras Gardens by horological philanthropist Baroness Burdett-Coutts that I wrote about a few months ago. Coincidence!

Happy reading, whatever’s on your bedside table, and very best wishes to you all for 2013.

Time to pay

This post was written by David Thompson

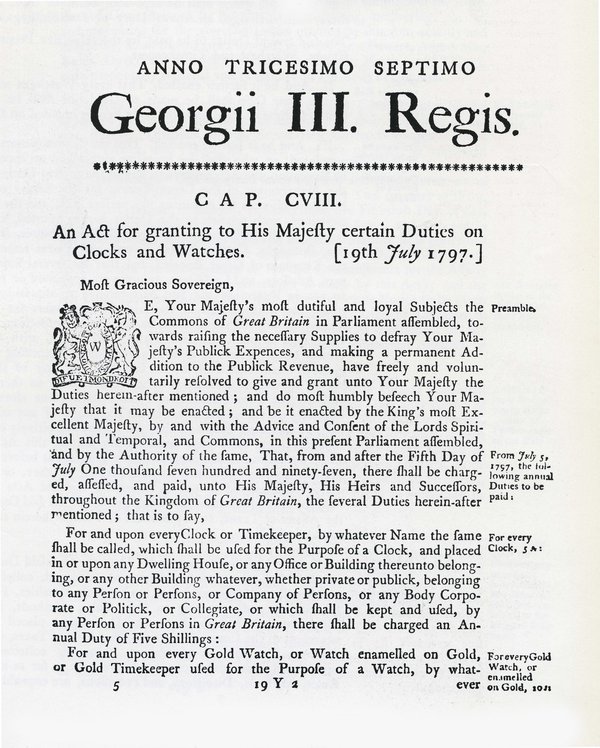

With all the current talk about taxation, I am reminded of a futile attempt to raise money introduced by William Pitt in 1797. Now commonly referred to as the Clock Tax it involved the levy of charges for clocks and watches under an act which was put into effect on the 5th July 1797.

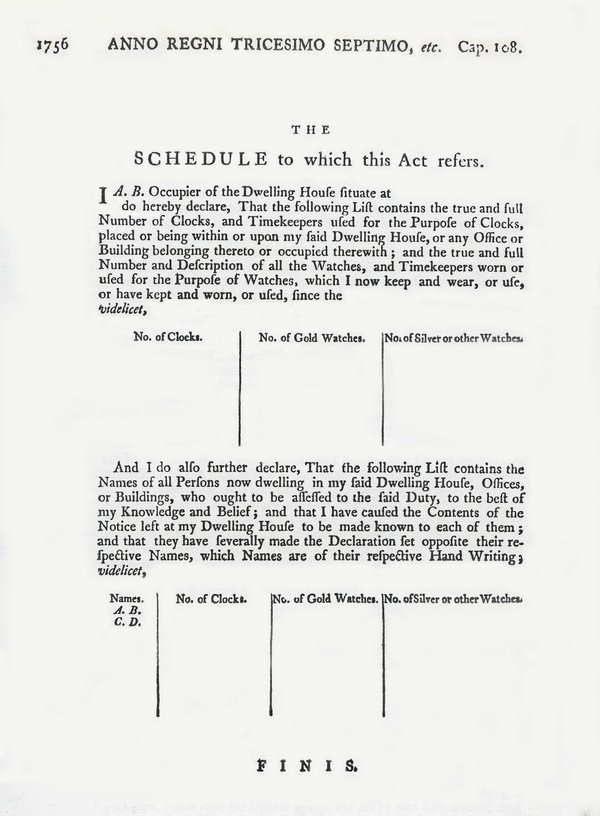

Under the act, levies would be charged at the rate of 5 shillings for every clock and 10 shillings for every gold cased watch or a watch with a case enamelled on gold. Silver and base-metal cased watches would incur a charge of one shilling and six pence. Householders, tenants and businesses alike were to provide a signed declaration of all the clocks and watches in their possession for the purposes of assessing the amount to be paid. Inspections would be made and the taxes levied according to the number of items.

Of course, people hid their clocks and watches and made false depositions to such an extent that the whole idea became unworkable and was quickly abandoned.

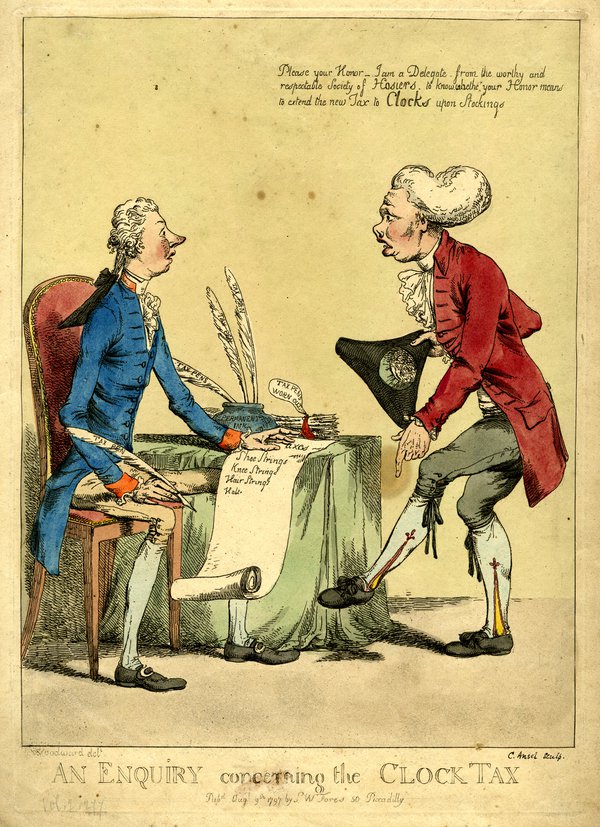

At the time of the tax a rather splendid satirical print was made suggesting that as the tax was something of an absurdity, perhaps the government were considering levying a tax on the embroidered decorations on stockings which are called ‘clocks’. The coloured print was made by A.C. Ansell in the style of the well known caricaturist George ‘Moutarde’ Woodward and published by S.W. Fores of 50 Piccadilly, London, on 9th August 1797.

With the increasing use of mobile phones as time-tellers, perhaps the answer today is a tax on these ubiquitous items!

(Thanks to Marjorie Hutchinson for timely advice)