The AHS Blog

…on the other hand

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

On the one hand we have simple, easy to use, single-handed dials. On the other hand, some dials are not so straightforward.

This clock has 'fly-back' or 'retrograde' hands. The hands proceed clockwise as usual but when they reach the end of the scale, each will spring back and then immediately resume its count.

This design allows the dial to have twice the diameter of a circular dial within a given height. This, together with the semi-circular form, makes these clocks suitable for positioning over doorways and they were sometimes integrated within wall panelling.

Fly-back hands are still a popular feature in watches, although these are usually (but not always) the preserve of high-end watches.

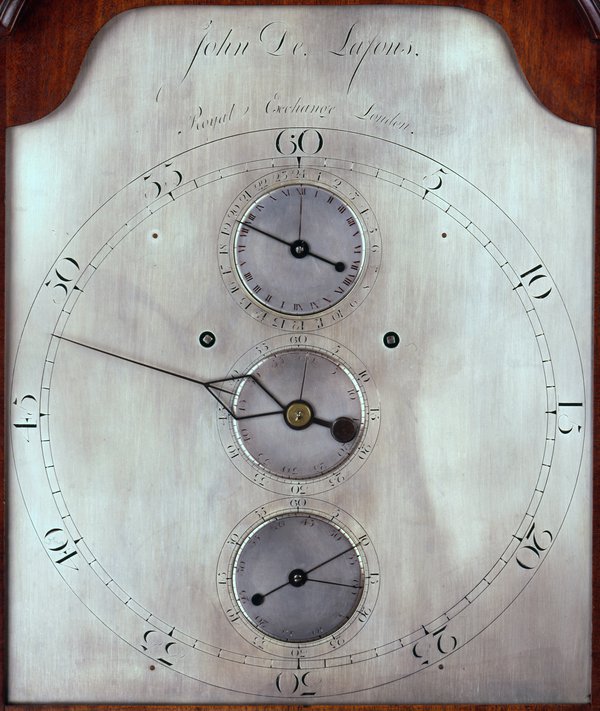

The dial of this regulator (that I have mentioned before for its escapement) has the typical features which facilitate the use of these clocks in observatories and laboratories. All hands are positioned on their own centres for disambiguation. The hours are relegated to a small subsidiary dial and only the minutes have a large hand, for accurate observations.

Less typically, however, this regulator indicates two different systems of time using only one set of hands.

It shows mean sidereal time against the numerals on the main dial plate and mean solar time against the small discs. A mean sidereal day is 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds, i.e. it is about 4 minutes shorter than the 24 hour mean solar day. The discs rotate slightly faster than the hands so that after each day they have accrued the 4 minutes difference. This system is called a differential dial.

Having a clock show both sidereal and solar time might have been a convenience, but a respectable observatory might well be expected to have had separate regulators for providing the required times and so it is possible that this design may have been conceived rather for the use of the (wealthy) amateur.

This watch has not just hands, but arms and fingers too! It is a type of watch known as “bras en-l’air”, which translates as “hands in the air” (and certainly not “bras in the air” – which might apply another aspect of horology altogether). When the pendant is pushed the soldier raises his arms, holding pistols to point at minutes (left) and hours (right).

An experiment in ‘florology’

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

Recently, I have been looking at the role of timekeepers in the history of science and whilst reading around the pre-pendulum era, happened upon a blog-worthy experiment conducted by Athanasius Kircher (1601/2-80).

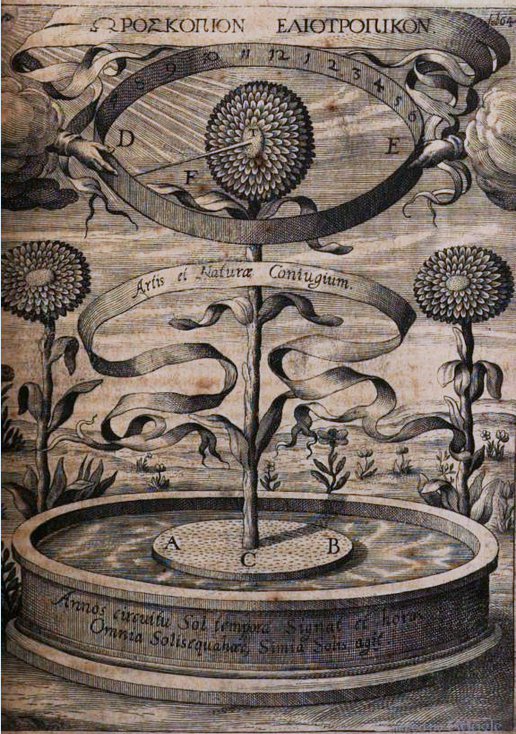

Kircher, a German Jesuit polymath, applied the then known phenomenon of heliotropism as a method of timekeeping.

He thought that the daily motion of sunflowers as they followed the Sun was caused by magnetic influence and thus inferred that they could be usefully used as a clock. As can be seen in his magnificent illustration, Kircher planted the sunflower in a cork pot and floated it on water, providing a frictionless pivot, and inserted a pointer through the flower to indicate time against the annular chapter.

Kircher noted that his clock was disturbed by the slightest of breezes and, when kept away from sunlight, it withered and its motion slowed. This, however, did not end the experiment. He tells us that he had the good fortune of meeting an Arab trader who happened to have amongst his aromatic wares a substance with similar horological properties to the sunflower.

The deal was struck and Kircher parted with his sundial signet ring for the horological stuff.

It has to be said that this episode is possibly a theatrical device to colour the account and introduce the use of sunflower seeds and root instead of the plant itself, but worth repeating – even if it’s just an excuse to show a beautiful horizontal sundial ring!

Today, we know that this diurnal motion is caused by sunlight and so Kircher’s clock could never have worked in the way intended, but one cannot help admire his ingenuity in applying a mystery of the physical world to tell the time. M. Becker’s 2011 time lapse movie shows that it is possible to use a flower as a twenty-four hour clock, but only in summertime at a latitude close to the north or south pole.

Graveyards, clocks and bombs

This post was written by James Nye

Things end up in graveyards at the end of their lives, but monuments to the passing of much else can be found in other locations.

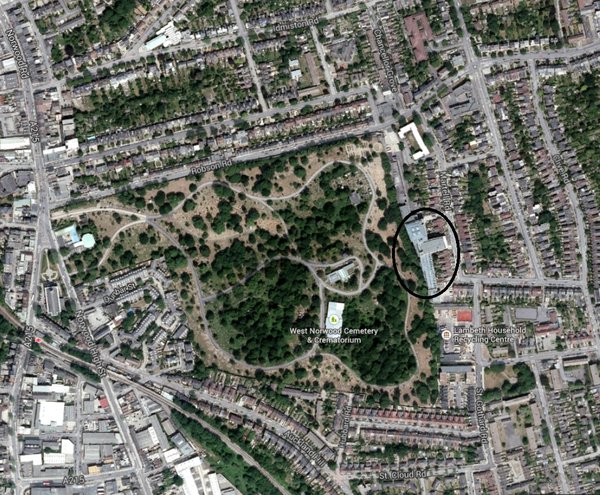

I live in West Norwood, home to one of the ‘magnificent seven’ London cemeteries.

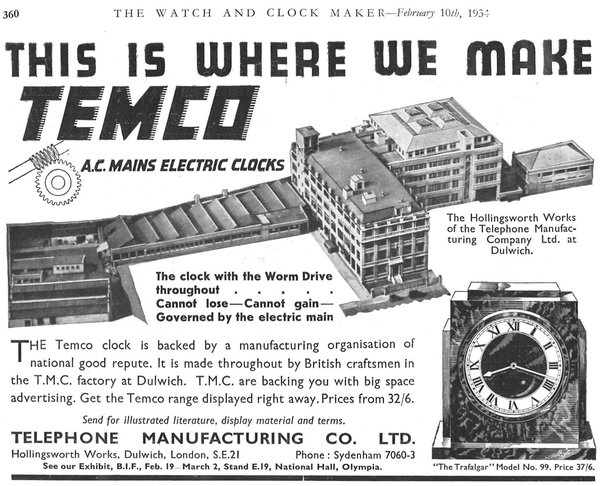

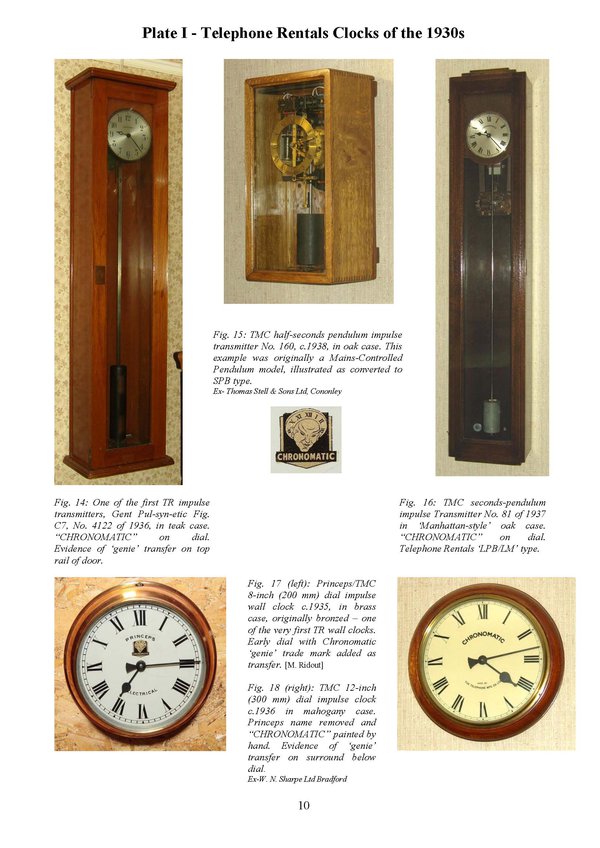

On its eastern boundary lies the Park Hall Business Centre. This thriving modern enterprise occupies the former Hollingsworth Works of the Telephone Manufacturing Company (TMC).

This firm did just what its name suggests, but was also a prolific maker of industrial timekeeping systems, rented out under the name Telephone Rentals. TMC’s ‘TEMCO’ synchronous clocks are featured in the latest NAWCC bulletin.

TMC occupied the Dulwich site from the early 1920s, employing a large local workforce—1,600 by 1937. Workers from the other side of Norwood Road used to talk of ‘walking the wall’ to work, following the long cemetery flank wall, down Robson Road.

Involved in contemporary ‘hi-tech’, the factory was a natural wartime target—Gerald Wells’ extraordinary autobiography describes twenty-seven bombs falling on the cemetery, targeting TMC, but then the Luftwaffe became:

‘fed up with wasting bombs on Norwood Cemetery so they decided to get the TMC factory by lowering a large naval magnetic mine on a parachute over the building. My sister Margaret watched it come down from an upstairs window […] it knocked seven colours of s*** out of our little Congregational Church’ ( click for a bombsight map —work in progress).

So Hollingsworth Works survived, and TMC/TR had a more successful post-war life than many clock-related concerns.

You can learn much more about the company’s life and products from a superb paper by Derek Bird—these technical papers are a feature of EHG membership. Why not e-mail me to get on board? And put 7 September 2014 in your diaries—part of Lambeth History Month—when The Clockworks will offer a special locally-themed event, featuring TMC.