The AHS Blog

Changing times in Germany

This post was written by David Rooney

We call it British summer time, but the first country to advance its clocks during the summer was Germany, which inaugurated a daylight-saving scheme in April 1916.

A letter, written 100 years ago this week and found buried in a museum archive, holds an important clue as to how the idea reached the top of German government just days before the outbreak of the First World War.

The champion of daylight-saving, British house-builder William Willett, had spent many years campaigning around the world for his time-shifting scheme to be adopted, and had become a regular correspondent with Henry von Böttinger, a prominent German chemist and industrialist who had been appointed to the Prussian House of Lords in 1909 by the German Emperor, Wilhelm II.

In 1913, von Böttinger had written to Willett to say that he was 'still pushing the Time Saving Question' and had raised the matter with the Prussian Minister of Public Works and the Association of German Chambers of Commerce.

But it was on 21 June 1914 that von Böttinger wrote again to Willett, this time with news that he was about to take the daylight-saving proposal to Germany’s highest authority.

'I have meantime taken note of your wish to have the subject laid before the German Emperor—and as His Majesty knows me personally and very well, I have at once made a written report to him and have asked him to devote his interest to the furtherance of this great object. As soon as I have another personal interview with His Majesty I shall not fail to bespeak the subject with him and thus bring the matter still closer home to him.'

Seven days later, Kaiser Wilhelm’s friend, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated, and Europe began its plunging descent into war.

This was the last letter William Willett received regarding his international daylight-saving campaign, and a few months later, while on a business trip to Spain, he contracted influenza and died.

We will never know the full circumstances of Germany’s adoption of daylight saving time in 1916, but it is possible that this letter between two influential international businessmen represented the crucial turning point in Willett’s campaign—though it was a campaign he did not live to see realized.

What is certain is that technology and politics are inseparable: ideas need powerful backers, and the German Emperor in 1914 was truly one of the most powerful men in the world.

Keeping in touch with time

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

A common feature of watches and clocks of the 16th century are touch-pins. These are raised studs located at each hour position on the dial, with that at the 12 o’clock position typically being longer and sharper to provide a point of reference.

These enable the time to be read by feeling the position of the single, robust, hour hand.

This was useful as it was not possible to simply switch on a lamp to read the time at night. An added benefit might have been that the time could be read discretely under one’s robes.

This is a later variation of touch indication, known as a “montre à tact” (“touch watch”).

The exposed hand does not turn with the movement but it is moved manually, clockwise, until it stops at the right time. This is read against touch-pins that are located on the edge of the case.

These watches are also sometimes known as “blind-man’s” watches but, although they could have served as such, they were conceived as night watches.

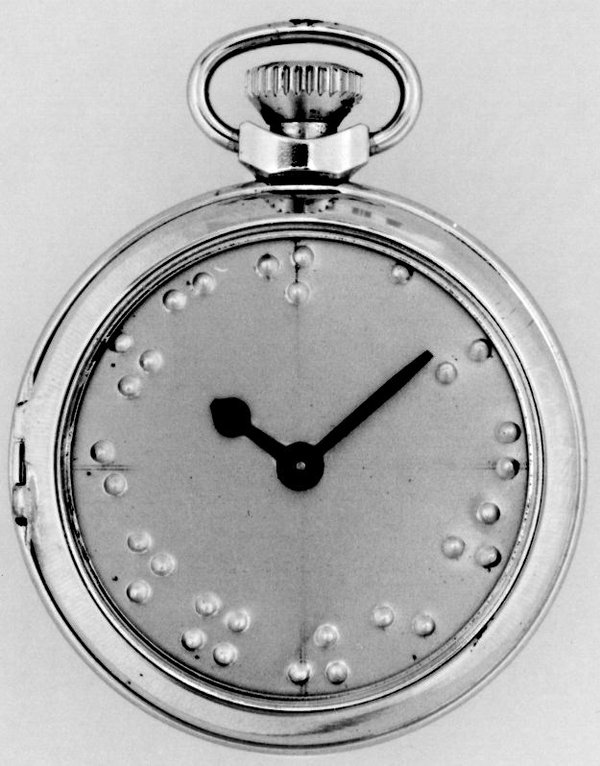

This watch, however, was clearly designed to be used by visually impaired persons as it has Braille numerals on the dial.

Mass production of watches and clocks became established in the 19 th century and it enabled them to be affordable to the masses and, subsequently, the massive new market enabled a much greater variety to be economically viable, including this Braille watch.

This wrist-watch bears the latest incarnation of touch indication.

The time is indicated by steel ball bearings which run in tracks, positioned by magnets driven by the movement within the case – the hours around the perimeter and the minutes on the front of the watch.

The balls are easily displaced, which prevents damage to the movement, but are easily relocated with a twist of the wrist.

The watch was conceived for use by visually impaired persons, but its elegant design appeals to a far larger market. The development of this watch somewhat parallels that of the Braille watch, as it also depended on a fundamental development in technology and economics.

This watch was brought to market through internet “crowd-funding”, whereby many individuals invest a relatively small amount each to raise the total capital necessary to fund the development of a product (in this case enabled by Kickstarter). Crowd-funding can enable some exciting projects to succeed which might have been rejected by more traditional investors.