The AHS Blog

Chronometers in hell

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

In my previous post, ‘Having a smashing time’, we saw how watches are being tested for shock resistance, which can involve some pretty heavy handling.

Another method of testing timepieces is prolonged exposure to heat and cold. This was especially important for marine chronometers, who would travel to all parts of the globe, so it was important to determine to what degree their rate was affected by temperature fluctuations.

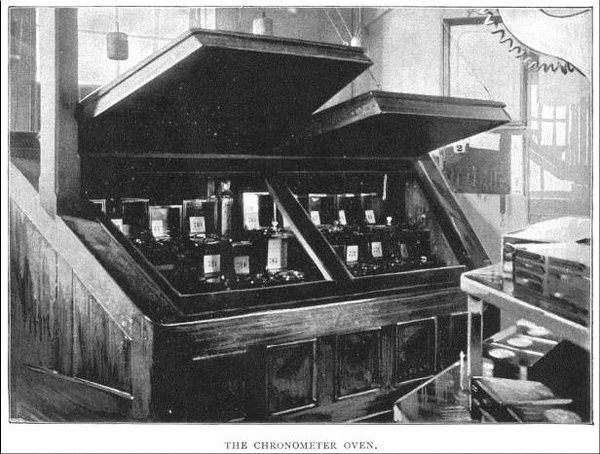

The Time Department at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, where the rate of chronometers was tested, had a large oven in which chronometers were kept for eight weeks at a temperature of about 85 or 90 degrees Fahrenheit, that is around 30 degrees Celsius.

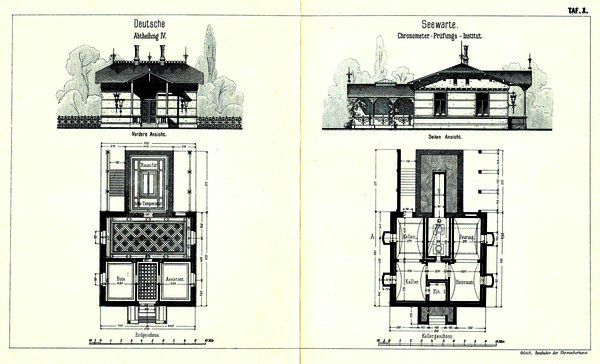

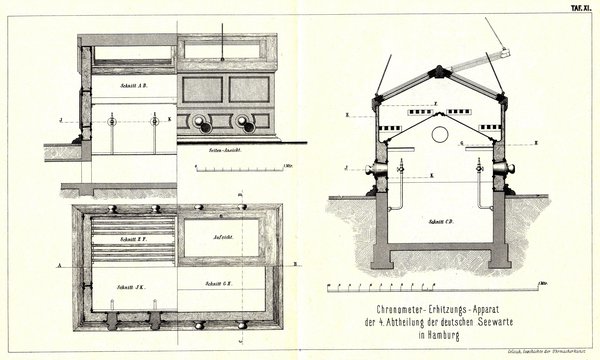

A recent article in Antiquarian Horology had a section on chronometer testing facilities in 19th-century Germany.

In Hamburg they had both an ice cellar and a gas-heated oven. The naval observatory in Wilhelmshaven was less well equipped:

'Neither an ice cellar nor a heating apparatus was available. The radiators of the central heating acted as makeshift for the latter, and tests in lower temperatures were conducted in winter by opening the windows. Sometimes the required temperature of 5º could not be reached due to mild weather'.

Manufacturers of chronometers could have their own heat and cold testing apparatus.

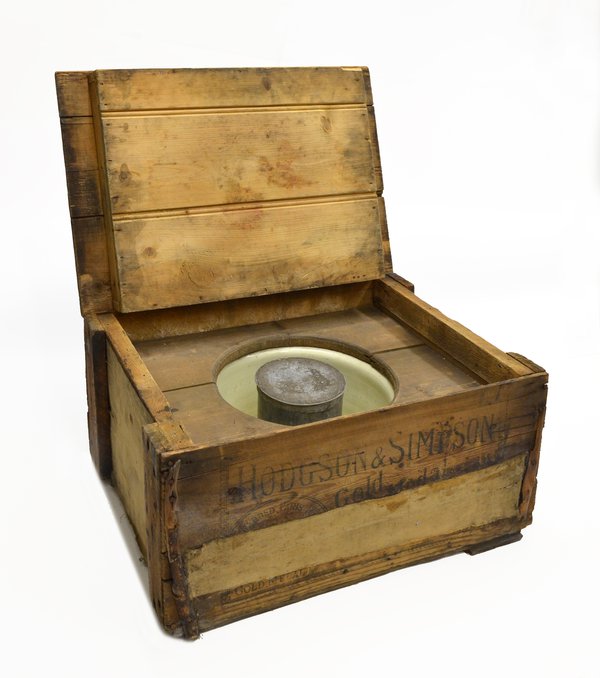

An oven and an ice-box used by the London-based watch and clockmakers Daniel Desbois and Sons are in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. Normally these two objects are kept in storage, but some years ago they were taken out for display in a temporary exhibition ‘Time Machines’.

When I visited the exhibition, the curator, Dr Stephen Johnston, told me that at first sight some visitors thought the ice box was a toilet!

Sir George Airy, the late Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, in one of his popular lectures drew a humorous comparison between the unhappy chronometers, thus doomed to trial, now in heat and now in frost, and the lost spirits whom Dante describes as alternately plunged in flame and ice.

He was referring to Dante’s La Divina Comedia, Book One: Hell, III, 76-82:

'There, steering toward us in an ancient ferry came an old man with a white bush of hair, bellowing: “Woe to you depraved souls! Bury here and forever all hope of Paradise: I come to lead you to the other shore, into eternal dark, into fire and ice.”'

Commemorating an invasion that never happened

This post was written by Rory McEvoy

Last month saw the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic era. To mark the anniversary, this week’s blog posting looks at two curious watch dials. The unusual point being that they both appear to come from the same manufacturer, but were made to celebrate victories on both sides of the conflict. One of which never happened.

The first of the two watch dials was made around 1798 when the prospect of a French invasion of England was real and, for many, a terrifying prospect.

Rumours abounded of the French rafts that would carry tens of thousands of troops and weapons to English shores. The images of these vessels distributed by the printmakers ranged from the allegedly factual to the overtly ridiculous.

The French perspective was bullish about the prospect of invasion. Not only were they confident of success, but they also believed that the English would, for the most part, welcome the invasion.

Gillray’s print (above) records that there were indeed those who may have welcomed the French. Whig collaborators are shown on the right-hand-side of the picture trying to winch the French transporter ashore and their efforts are being foiled by Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, seen as the wind blowing the flotilla to destruction.

The dial depicts the ‘descente en Angleterre’ with a more traditional fleet of ships sailing towards the heavily defended English shoreline and serves as a useful glimpse into the mind of the manufacturer, keen to capitalize on the bullish French mood of early 1798.

The scene on the second dial is identifiable as the Battle of the Nile because of the burning ship on the left-hand-side of the image. This represents the French Flagship, L’Orient, which exploded with such violence that fighting was temporarily halted and it became a symbolic feature in popular representations of the Battle.

There is a near-identical row of box-shaped buildings placed along the horizon on both dials. This suggests that they both came from the same source. Such buildings seem more appropriate for the northern coast of Africa than the southern shores of Britain and so it was probably a generic depiction preferred by the artist.

As an asides, the invasion watch dial has a later counterpart in the Museum’s medal collection. A rare sample medal was struck in 1804 with dies intended to be used in London by the victorious French conquerors. Despite amassing a substantial force in the Boulogne area, the embarkation was prevented, principally by the diversion of troops and resources to the Battle of Ulm and, secondarily, by the English blockades.

Inspired reforms – magnificent outcomes

This post was written by James Nye

In May 2014, I blogged about a competition to devise uses for new-old stock 1950s Calibre 5000 Reform movements that had turned up at the annual Mannheim electro-fair.

I judged the entries on 24 May this year, and what an amazing event to witness. Here was a beautifully executed movement, simple, reliable, long-lived, but criminal to hide.

How to incorporate it in a modern design, and achieve a functional clock, when the attractive side of the movement would necessarily normally face the rear? In significant style, it turns out……

Ivo Creutzfeldt ignored convention and went for pure schlock with his tongue-in-cheek ‘winged chariot entry’.

Thomas Schraven offered a couple of entries, one channelling a strong modernist theme – using two movements, one for display, the other for timekeeping.

Eddy Odell showed considerable lateral thought, introducing the movement into a glass mug, keeping the movement visible to the top, while driving digital minute and hour bands in the base, the battery neatly hidden.

Till Lotterman and his home team colleagues offered a remarkable test exercise. Using original parts, they recut elements to form a tourbillon, brought out on the dial side of the movement, achieving real spectacle ( film here).

Not only this, they 3D printed a stylish stainless steel dial, and also 3D printed an open-sided plastic tubular case, with internal mirror to reflect the movement. Later we were treated to a lecture on the extraordinary possibilities emerging for 3D printing.

Finally, the most talked about item in the competition, Frank Dunkel’s inspired diorama clock, using the Reform at the centre of a roundabout, driving hidden arms carrying neodymium magnets, in turn propelling a VW Beetle (minutes) and VW van (hours) against perimeter hour markers ( film here ).

Power even arrives by wire supported on telegraph poles. Absolutely inspired!

The whole party retired to a restaurant for the evening, at which, amidst characteristically heroic levels of consumption, we celebrated the amazing results of our competition – prizes all round.