The AHS Blog

Time for everyone

This post was written by David Rooney

In 1947, the British chronicler of timekeeping, Donald de Carle, wrote the following tribute to American engineer Warren Marrison: ‘it is to him we are indebted for the most accurate timekeeper in the world.’

Marrison worked at the Bell Telephone Laboratories with J.W. Horton. And in 1927 they had made the first quartz clock. It was a game-changer.

The electric clock pioneer Frank Hope-Jones sought to calm fears about the new technology, explaining in 1944 that ‘There is no reason to be afraid of the quartz clock. The trick whereby the vibration of a resonator can be maintained by a vacuum tube – the triode valve of our radio set – is easily learnt.’

He was right. By the end of the Second World War, Britain’s national timekeeping service was based on quartz clocks and today the technology underpins most modern time measurement.

But I think the quartz clock was more than just a new technology. It was one of a series of twentieth-century innovations that represented a new scientific politics, presented publicly as an alternative to nationalism that was ripping the world apart at the time.

If you want to know more, and to contribute to the debate, you might be interested in ‘Time for Everyone’, an international symposium being held at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, on 7 – 9 November this year. I’ll be there speaking about quartz clocks and the public politics of science, but if that’s not to your taste, you’ll also be able to hear other AHS speakers including Chris McKay, Jonathan Betts and James Nye, as well as a host of fabulous presenters from around the world.

The dog watch

This post was written by David Thompson

Anyone with connections with the sea and ships will tell you that the dog watch is a period of service between 4.00pm and 8.00pm and that it is split into two watches, the first and second watches on board ship.

Today there are any number of charms for bracelets and pendants in the form of dogs and I don’t doubt that there were all sorts for sale at the recent Crufts dog show. How many would guess, however, that you could buy a watch in the form of a silver dog in the 17th century.

A unique example exists in the British Museum collection where a silver-cased watch in the form of a dog can be found. The watch maker was Jacques Joly who lived in Geneva between 1622 and 1694. He made this watch in about 1660. It was during the middle period of the 1600s that there was a fashion in watches looking like real and animate objects, tulips, fritillary flowers, sea urchins and so on.

If the little dog needed a friend, there is a charming little lion living in the collections in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, this one with a movement made by Jean Baptiste Duboule. Of interest to both the dog and the lion is a little cast silver watch in the form of a hare which was stolen some years ago from the Musée de L’Horlogerie in Geneva. It has a movement inside signed, P. Duhamel, Geneva, and, as far as we know, a unique example of a watch case in that form.

Where can I see antiquarian horology?

This post was written by Oliver Cooke

I refer not to our society’s journal (which you can of course see by joining us!), but where can we see old clocks and watches?

I clearly remember dearly wanting to know this information when I first became properly interested in horology. Now I am in the loop and am l pleased to be able to share some good tips.

There are the major collections in national museums; the British Museum, the Royal Observatory Greenwich and the Science Museum. But since these are well-known, let their plugging end there for now and let instead us look at a couple of less well known collections from different ends of the country.

Starting down South, there is the finest private collection outside the institutions mentioned above – the Harris collection, in Belmont House in Kent. The collection is wide ranging with examples from all the major clock making countries and periods, but there is a strong focus on England’s horological ‘Golden Age’. Not only does the house have its collection, but it is a beautiful place to visit in its own right – it is a magnificent neo-classical house set in beautiful gardens in the North Downs.

So, if you have a partner who likes horology a little less than you, they will not be disappointed when joining you on a visit there. Jonathan Betts, sometimes author on this very blog, conducts a clock tour at 1.30 pm on the last Saturday every month during the season. Prior reservation is necessary – please see the Belmont House website for details.

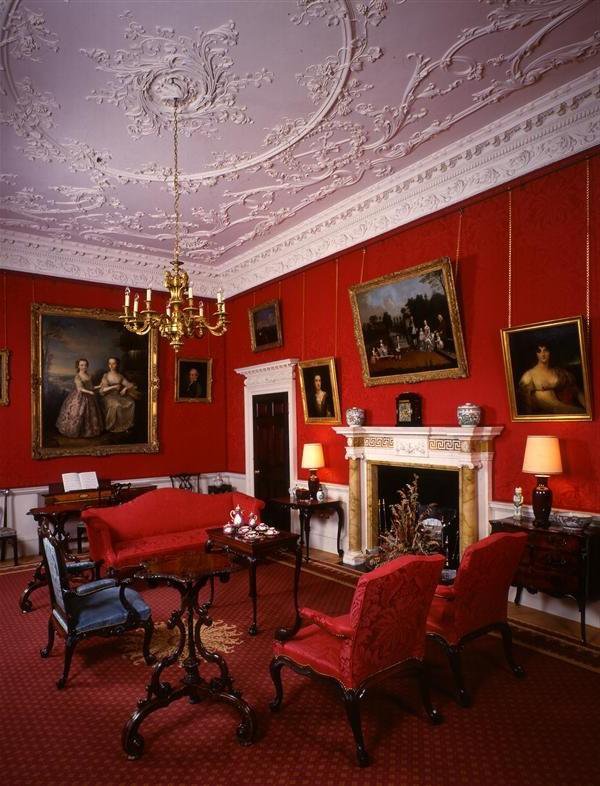

Now, heading up North, another great place to visit is Fairfax House in York. Fairfax Houses houses the collection of Noel Terry (grandson of the founder of the confectionery firm), one of the finest private collections of the twentieth century.

Again, this House has much more to offer than just clocks and watches and of course it is bang in the middle of York, a city worth a visit in its own right. The house is open every day except Mondays for most of the year – do check their website.

There are more collections to tell of, which can follow in a later post. Keep reading!