The AHS Blog

'Pin a long time...

This post was written by Dale Sardeson

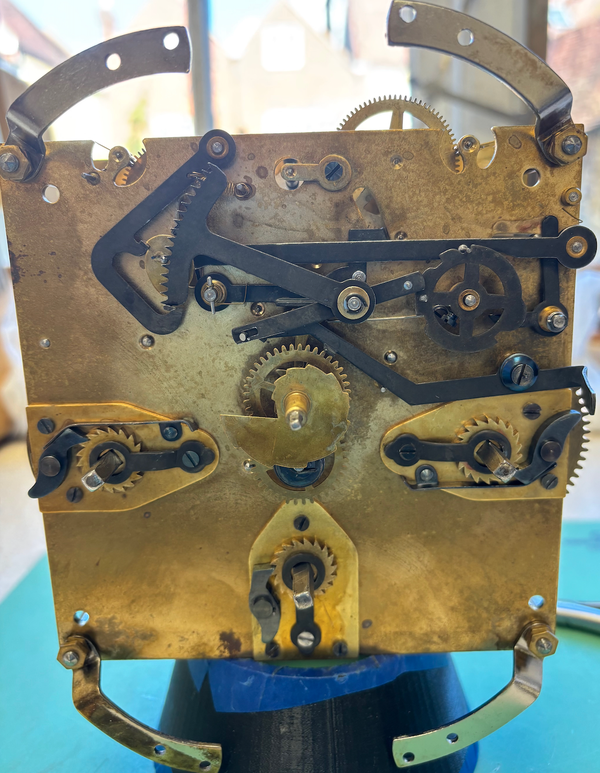

I recently worked on an Enfield K1 movement which had survived with remarkably few interventions up to now. I can’t believe it had never been taken apart, as it was in working order, and, while quite grubby, was not in any way as choked up with old oil as you would expect a hundred-year-old clock to be if it had never been cleaned. There were also no signs that it had ever been rebushed, which is a rarity.

The clock’s place in a National Trust collection probably accounts for how it has survived without the usual extent of repairs you’d find to a clock of this type in a domestic environment. Even institutional record-keeping tends to get spottier the further back in time you look, so I can’t say for sure, but I expect that the clock has probably spent a fair portion of its life in static storage.

We might wonder why it really matters whether the clock has come apart before or not; a clock of this age is hardly likely to have been mutilated beyond all recognition, and even if it were, this period of production has furnished us with countless other examples with which we can investigate that time’s materials, finishes and techniques.

But the reason it matters in this instance is precisely because it seems to have been disassembled so few, if any, times: it gives us some valuable information about a small, and often overlooked, detail – the securing pins.

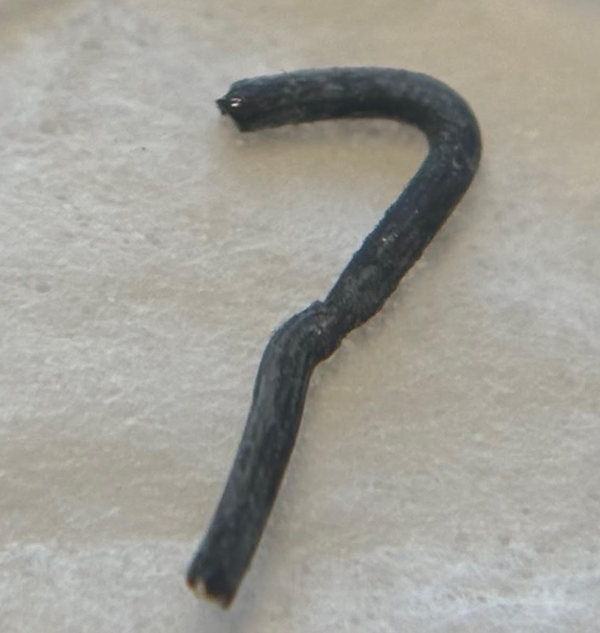

Taper and other securing pins are often replaced as a matter of routine during clock servicing, not least because they get broken or damaged during removal (especially S-type pins because of the internal stresses introduced during bending), but also because they are largely considered an unimportant consumable item. It is rare to come across a taper pin on a clock movement that one can truly be sure is any older than the last service date.

On this Enfield movement though, I noticed something I had never seen before (and I also had a good ask around some of my much more experienced colleagues, who said the same), in that most of the S-pins on this clock were made from sherardised steel.

Sherardising is a method of applying a corrosion resistant coating, similar to galvanising, in which the steel is enclosed in a rotating drum with zinc dust and heated to the point the zinc vaporises and diffuses into the steel surface. It is the coating procedure applied to the steel of the underdial-work on Enfield K1 movements, and gives them a blue-black, grainy appearance.

Anyone who has worked on their fair share of 20th century English clocks is likely to have seen sherardised components, as it’s not just the K1 movements on which it was used, but I have never seen it applied to a securing pin before.

Based on the evidence that this clock has rarely, if ever, been fully disassembled, it seems to me a fair conclusion that these pins may well be original to the clock’s manufacture, and the reason that I, or anyone else I spoke to, have never seen them before is because we so rarely get to work on a clock of this age that hasn’t already been taken apart and had the pins replaced multiple times.

If correct, I think it’s a fascinating insight into the early designers of these often-maligned mass production clocks, to find that they considered even the smallest detail of having a protective coating on their securing pins.

(Note: Whilst the subject of this blog is a National Trust object, I am an independent conservator, and all text and views are my own.)