The AHS Blog

Not quite bombproof

This post was written by James Nye

It has become a cliché to describe solutions or products as bombproof—supposedly immune to attack or criticism—without ever imagining real bombs. This word came to mind recently when considering the survival of three turret clocks in near unbelievable circumstances.

My first encounter with such a story came in uncovering the later life of the clock installed at London’s Chelsea Old Church in 1761, made by Edmund Howard (1710–98). During the Blitz, on the night of 16/17 April 1941, several 1,000 kg aerial mines destroyed the church.

Informed opinion suggests the fall of over 1,000 tons of masonry as the tower collapsed, bringing down the clock movement. In the late 1950s it was observed by AHS members in the workshops of Dent, where bomb damage was evident: the central train bar can be seen bent over at the top. Remarkably, a seemingly fragile wrought-iron clock survived such a catastrophic fall amid the rubble.

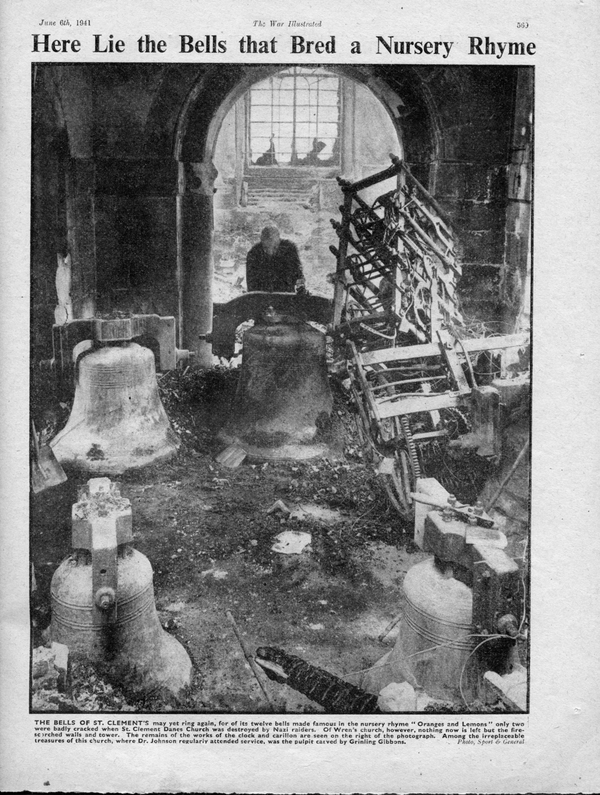

This was not unique. On the worst night of the Blitz (10/11 May 1941), incendiary bombs hit St Clement Danes Church in London’s Strand, nearly destroying the entire fabric. As a photograph from Sports & General shows, the immensely heavy Langley Bradley clock and its tune player nevertheless reached ground level relatively intact. The clock was nearly 10 feet wide and 6 feet tall, with great wheels about 32 inches in diameter and perhaps 1¾ inches thick, set in a massive cast-iron frame. This colossal assembly fell as the floors of the tower collapsed in the fire, yet the photograph suggests remarkably little obvious damage.

A final and related example lacks quite the same drama, but is no less intriguing. The Inner Temple Library was hit earlier than the other two sites. It was early on 19 September 1940 that a bomb sliced through the library tower, destroying a large part of the structure and one of the four 6-foot clock dials, perhaps damaging the John Moore & Sons hour-striking clock installed as recently as 1871.

When the compromised tower was demolished soon after, the dials had already been removed, inviting speculation that careful horological salvage had taken place. If so, one might hope the movement survived and was recycled, as we also hope for the Chelsea and St Clement Danes clocks. If anyone has any information on the later histories or whereabouts of these three clocks, all now lost to view, please let me know!

Circumstantial evidence

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

In 1955, in Kharkiv, Feodosii Fedchenko finally cracked the isochronous pendulum, a horology goal as old as Christiaan Huygens. Fedchenko’s ‘Model AChF-3’ clock was the most accurate pendulum clock ever created – though since it was mid-century in the USSR, it would be several decades before news of his invention reached the wider world (which had, in any case, largely moved onto quartz).

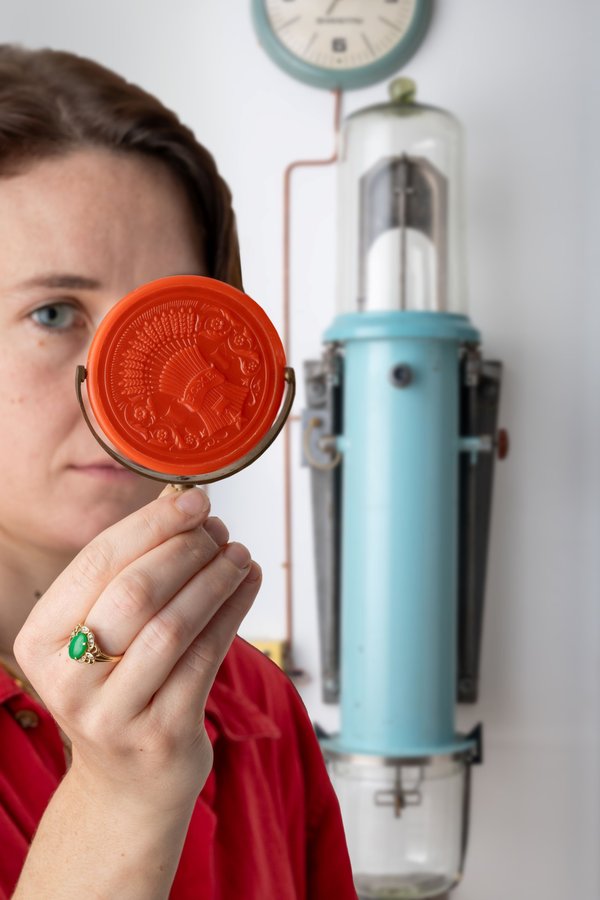

The collection at The Clockworks includes two Model AChF-3 tank clocks: number 10 and number 26. Both have a small adjustable mirror to help illuminate the pendulum scale. However, recent conservation work has revealed that the mirror in number 26 – previously at the Obninsk Institute for Nuclear Power Engineering – is not original. In contrast to the metal observatory mirror supplied with number 10, it is a civilian compact, its orange plastic backing emblazoned with a wheatsheaf emblem and the motto ‘VDNH’ (ВДНХ).

Further research reveals that ‘VDNH’ was the acronym used by the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, a trade show and amusement park that opened in Moscow in 1939. Here, over a geographical area the size of Monaco, visitors could stroll along grand avenues and – for a time – underneath Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, eventually reaching pavilions dedicated to various areas of national endeavour, from engineering and space exploration to beekeeping. From the 1960s, this included the ‘Pavilion for Atomic Energy for Peaceful Purposes’, where, among other attractions, visitors could enjoy the lights of a working reactor.

Circumstantial evidence therefore suggests that one of the visitors to this pavilion was associated with the nuclear research centre at Obninsk, and interested enough to slip a ‘VDNH’ branded mirror into their pocket. Later, when the mirror in their laboratory clock broke, they knew just the thing to make a new one.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the story of the AChF-3 No. 26, which has always exemplified the paradox of the Soviet technological programme – its extraordinary ambition and achievement always inevitably tempered with a certain amount of making do.