The AHS Blog

The glorious prospect below

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

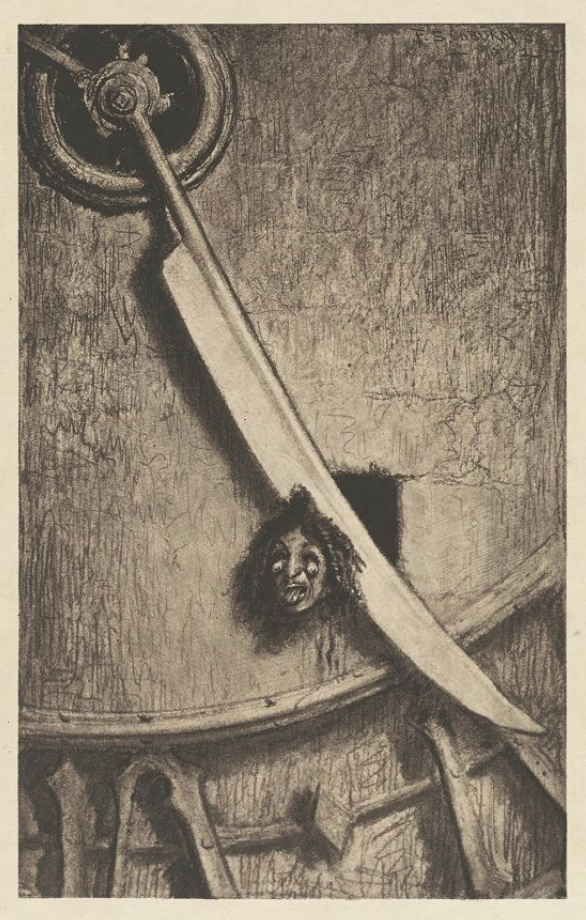

The author Kirby Draycott provided Synchronome with the inspiration (and image) for their 1934 advert featuring death by turret clock at Schaumburg Castle. However, Draycott had a precedent of his own.

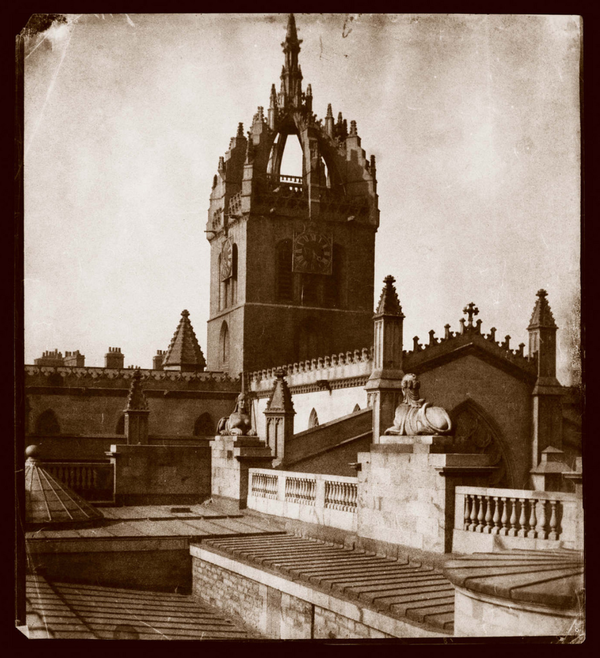

In 1838, Edgar Allen Poe published in Blackwood’s Magazine ‘A Predicament’: an ironic gothic parody about a young lady who sticks her head through an ‘aperture’ in the ‘vast, venerable’ steeple of a Gothic cathedral in Edinburgh – possibly St Giles', in Parliament Square – in search of a glorious view, only to discover she is stuck with her head through the dial.

The hands – ‘not … less than ten feet in length’ – are of steel, and fast advancing (a minute hand had been installed at St Giles' in 1797). However, Poe’s heroine is cheerfully unconcerned with her (titular) predicament and focuses on enjoying ‘the glorious prospect below’ until the hands’ advancement makes her eyes pop out, followed by her head, upon which she returns headless to the street.

Whereas the clock of Schaumberg was elaborately modified to accommodate Draycott’s imagined execution, Poe describes the dangerous aperture as a pre-existing ‘opening in the dial-plate’ through which the clock attendant can adjust the hands – though the heroine speculates that it ‘must have appeared, from the street, as a large key-hole, such as we see in the face of the French watches’. This presumably alludes to a winding arbor, in which context the comparison between a turret clock and a watch establishes a comical contrast of scale.

At the same time, Poe seems less interested in horological practicalities than the prurient associations of the giant ‘keyhole’, which suggests a quest for hidden (and forbidden) knowledge.

Ultimately, the heroine’s eagerness to penetrate mysterious holes is punished by what she herself dubs ‘the ponderous and terrific Scythe of Time’. For Poe (later to return to horological torture in ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’), decapitation by turret clock therefore provides an ironic illustration of time’s inexorable assault on youth – though perhaps here it matters less exactly what time it is.