Circumstantial evidence

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

In 1955, in Kharkiv, Feodosii Fedchenko finally cracked the isochronous pendulum, a horology goal as old as Christiaan Huygens. Fedchenko’s ‘Model AChF-3’ clock was the most accurate pendulum clock ever created – though since it was mid-century in the USSR, it would be several decades before news of his invention reached the wider world (which had, in any case, largely moved onto quartz).

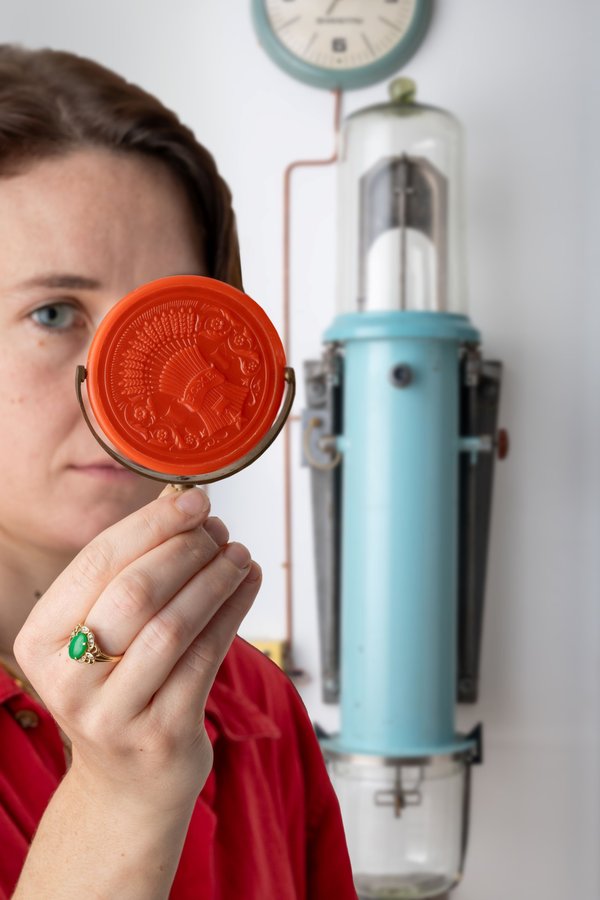

The collection at The Clockworks includes two Model AChF-3 tank clocks: number 10 and number 26. Both have a small adjustable mirror to help illuminate the pendulum scale. However, recent conservation work has revealed that the mirror in number 26 – previously at the Obninsk Institute for Nuclear Power Engineering – is not original. In contrast to the metal observatory mirror supplied with number 10, it is a civilian compact, its orange plastic backing emblazoned with a wheatsheaf emblem and the motto ‘VDNH’ (ВДНХ).

Further research reveals that ‘VDNH’ was the acronym used by the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, a trade show and amusement park that opened in Moscow in 1939. Here, over a geographical area the size of Monaco, visitors could stroll along grand avenues and – for a time – underneath Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, eventually reaching pavilions dedicated to various areas of national endeavour, from engineering and space exploration to beekeeping. From the 1960s, this included the ‘Pavilion for Atomic Energy for Peaceful Purposes’, where, among other attractions, visitors could enjoy the lights of a working reactor.

Circumstantial evidence therefore suggests that one of the visitors to this pavilion was associated with the nuclear research centre at Obninsk, and interested enough to slip a ‘VDNH’ branded mirror into their pocket. Later, when the mirror in their laboratory clock broke, they knew just the thing to make a new one.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the story of the AChF-3 No. 26, which has always exemplified the paradox of the Soviet technological programme – its extraordinary ambition and achievement always inevitably tempered with a certain amount of making do.