The AHS Blog

Circumstantial evidence

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

In 1955, in Kharkiv, Feodosii Fedchenko finally cracked the isochronous pendulum, a horology goal as old as Christiaan Huygens. Fedchenko’s ‘Model AChF-3’ clock was the most accurate pendulum clock ever created – though since it was mid-century in the USSR, it would be several decades before news of his invention reached the wider world (which had, in any case, largely moved onto quartz).

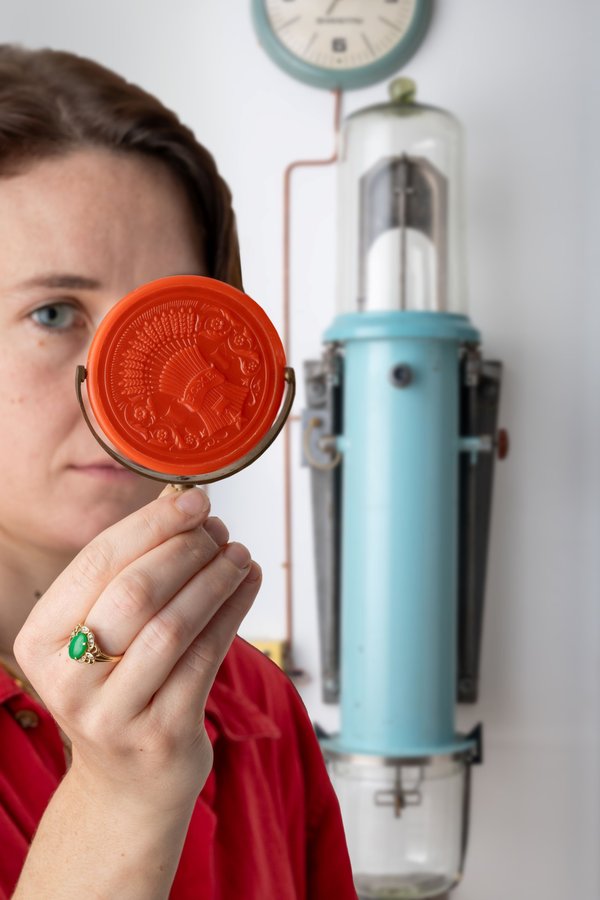

The collection at The Clockworks includes two Model AChF-3 tank clocks: number 10 and number 26. Both have a small adjustable mirror to help illuminate the pendulum scale. However, recent conservation work has revealed that the mirror in number 26 – previously at the Obninsk Institute for Nuclear Power Engineering – is not original. In contrast to the metal observatory mirror supplied with number 10, it is a civilian compact, its orange plastic backing emblazoned with a wheatsheaf emblem and the motto ‘VDNH’ (ВДНХ).

Further research reveals that ‘VDNH’ was the acronym used by the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, a trade show and amusement park that opened in Moscow in 1939. Here, over a geographical area the size of Monaco, visitors could stroll along grand avenues and – for a time – underneath Vera Mukhina’s Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, eventually reaching pavilions dedicated to various areas of national endeavour, from engineering and space exploration to beekeeping. From the 1960s, this included the ‘Pavilion for Atomic Energy for Peaceful Purposes’, where, among other attractions, visitors could enjoy the lights of a working reactor.

Circumstantial evidence therefore suggests that one of the visitors to this pavilion was associated with the nuclear research centre at Obninsk, and interested enough to slip a ‘VDNH’ branded mirror into their pocket. Later, when the mirror in their laboratory clock broke, they knew just the thing to make a new one.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the story of the AChF-3 No. 26, which has always exemplified the paradox of the Soviet technological programme – its extraordinary ambition and achievement always inevitably tempered with a certain amount of making do.

Help the British Museum preserve clocks and watches for now and the future

This post was written Oli Cooke, Curator at the British Museum

The British Museum is currently running an appeal to raise funds for expanded horological conservation. Let me explain why.

The museum holds one the world’s greatest collections of horology, with more than 8,000 items including 900 clocks, 3,000 watches as well as some 500 scientific instruments. It ranges from ordinary, everyday watches to masterpieces owned by kings and queens, made from the provinces of Britain to the furthest reaches of the globe, and from the dawn of mechanical horology to the present day.

The breadth and depth of the collection is remarkable and enables the Museum to communicate the global history, development and significance of horology like nowhere else.

The Sir Harry and Lady Djanogly Gallery of Clocks and Watches is the only gallery in the Museum with working objects and is alive with spinning wheels, living automata, oscillating pendulums, ticking, chiming and music, making it one of the most popular galleries.

Visitors spend more time engaging with working instruments and, for the keen student, there is no substitute for seeing a clock movement in action to gain an understanding of how it works.

You will find about 100 clocks and 90 watches in the gallery - we cannot possibly display all 8,000 items in the collection, but every single one is publicly accessible. Firstly, through the Museum website collection page and, if you need to view something in the metal, you can make an appointment to visit to the Horology Study Room.

Like all objects in the Museum, clocks and watches are subject to the ravages of time and must be looked after. Unlike most other objects, however, working machines require additional efforts. The British Museum is the only museum in the UK with specialist curator-conservator-horologists: Oliver Cooke and Laura Turner, both qualified horologists. However, caring for 8,000+ items is no mean feat. Clocks and watches contain delicate components and maintaining them demands dedication and meticulous attention to detail. Fortunately, a clock or watch in its dismantled state is the perfect time to study and record it in detail, and each piece can absorb many hours of work.

The fact is that we simply cannot keep up. The high volume of work can only be handled by adding more pairs of hands.

We are therefore asking for your support in building a fund that will enable us to recruit a specialist conservator. This will be a valuable investment in research, conservation and training. It is a fantastic opportunity for somebody to gain experience working on such an unrivalled collection.

Please visit britishmuseum.org/preserve, where you can donate via the Donate as a Member portal (even if you are not a member) or get in touch with me and I will be very glad to assist. It would be wonderful to recruit help in making yet more clocks and watches come to life in the gallery. Thank you.

Oliver Cooke, AHS Member and Curator of Horology, Department of Britain, Europe & Prehistory, British Museum.

Contactable at ocooke@britishmuseum.org or +44 20 7323 8324

Keeping time afloat

This post was written by James Nye

Clocks often need fixing, especially when badly worn or broken. But what about repairs before a clock reaches its first owner? Production lines like those at the Smiths alarm clock factory had systems for identifying rogue movements and adjusting them before they left the plant. Travel back in time and we can find occasions of things going badly wrong once the clockmaker had shipped an item, before it reached the client. Damage on a voyage was a risk.

When Thwaites received an order in 1763 for a turret clock for St Michael’s church, Charleston, South Carolina, the church officials were nervous. The clock was shipped on the Little Carpenter, commanded by Captain Muire, with instructions to pack the clock in that ‘part of the Vessell least Apt to Damage goods Either by Water, or Occasion Breakage by the Extraordinary Weight of Other Goods stowed Above, be Appropriated for the Clock and Bells as Bruising the One or Cracking One or more of the Others will be to us an Irreparable Damage’.

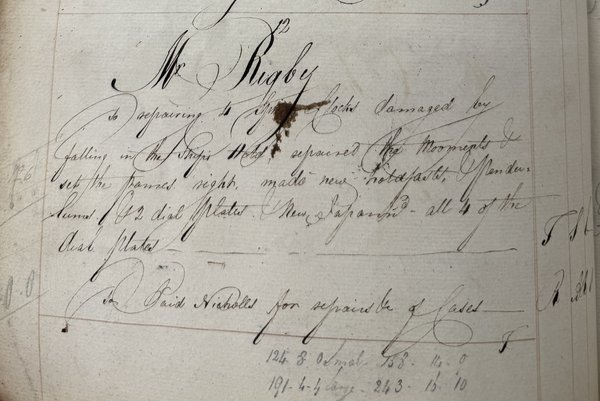

The clock survived the Atlantic, but another client was not so lucky. In September 1806, Thwaites invoiced regular client Mr Rigby, for ‘repairing 4 spring clocks damaged by falling in the ships hold, repaired the movements & set the frames right, made new holdfasts, & pendulums & 2 dial plates, new japanned all 4 of the dial plates’.

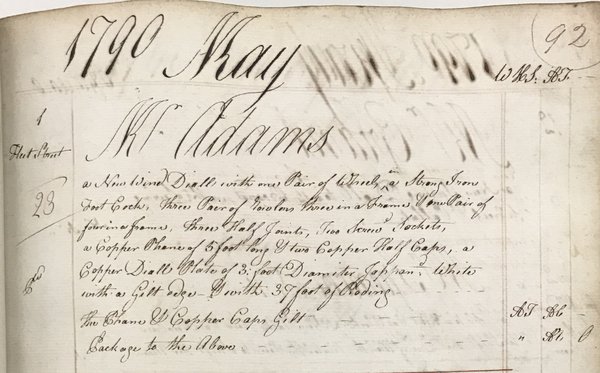

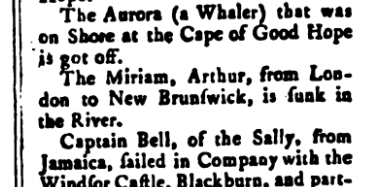

One more example – where remarkably we can recover even more detail. In May 1790, Thwaites supplied a wind dial to instrument maker George Adams of 60 Fleet Street. But in September it was back in the workshop where Thwaites cleaned ‘all the Work of a Wind Diall New Turned all the Wood Rowlers Painted the Rods New Jappann’d the Diall Plate New Gilt the Phane Repair’d the Packing Cases & Packed it up’.

Thwaites had dispatched the dial by ship, but in July 1790, the Miriam sank in the Thames on her way to New Brunswick. Some of the cargo was saved, among which were the packing cases, duly returned to Thwaites (‘sent back the Ship Having Sunk in the River Thames’).

One suspects the incident prompted some rueful reflection in Clerkenwell: proof that even the most careful packing cannot always prevent that sinking feeling.

References:

St Michael’s, Charleston, ‘The Bells and the Clock’, in George Williams, St Michael’s, Charleston (University of South Carolina, 1951), 234–308.

All aboard the Vitascope: a clock with a view

This post was written by Geoff A. Horner

Ever stumbled upon a clock that's more than just a time-teller?

Meet the Vitascope Illuminated Panoramic Electric Clock, a delightful creation from the Isle of Man that has been charming enthusiasts for over 70 years. Forget boring old tickers; this beauty features a miniature sailing ship that actually pitches and rolls on a painted sea, all while the sky behind it magically shifts from sunrise to sunset and moonlight.

Manufactured by Vitascope Industries Ltd between 1946 and 1958, these clocks were truly a product of their time. They were part of a post-war boom in plastic injection moulding, and while they might not have had 'real horological content' according to some, they certainly had real character. The Vitascope seems to attract the interest of even those who are uninterested in clocks.

Joseph Frederick Summersgill, the inventor and managing director, clearly had a flair for the whimsical. Beyond the clocks, Vitascope Industries also created sought-after flying saucers and other plastic novelties.

What made the Vitascope so popular? Its unique, animated diorama and the fact it came in a rainbow of colours. Plus, being mains synchronous, it was accurate and never needed winding – a true convenience for its era.

The Vitascope was marketed worldwide, as its developing patent history indicates, and, as the press noted in 1948, ‘the factory is working at top pressure just now on the Vitascope dioramic electric clock which is finding a ready market in different parts of the world’ (Ramsey Courier, 19 March 1948, 7).

While you might hear claims of them being rare, Vitascopes actually pop up for sale quite often. However, finding one in pristine condition can be a treasure hunt! They came with variations in case colour (from common creams and browns to rarer greens and reds), different hands, and varying chapter rings. Early models often featured specific combinations, like a cream case with brass studs and 'Empire State' hands.

The Vitascope is a testament to inventive design, proving that a clock can be a conversation starter and a miniature piece of art. It's a fun and fascinating glimpse into mid-century design and a reminder that even everyday objects can hold a touch of magic.

The glorious prospect below

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

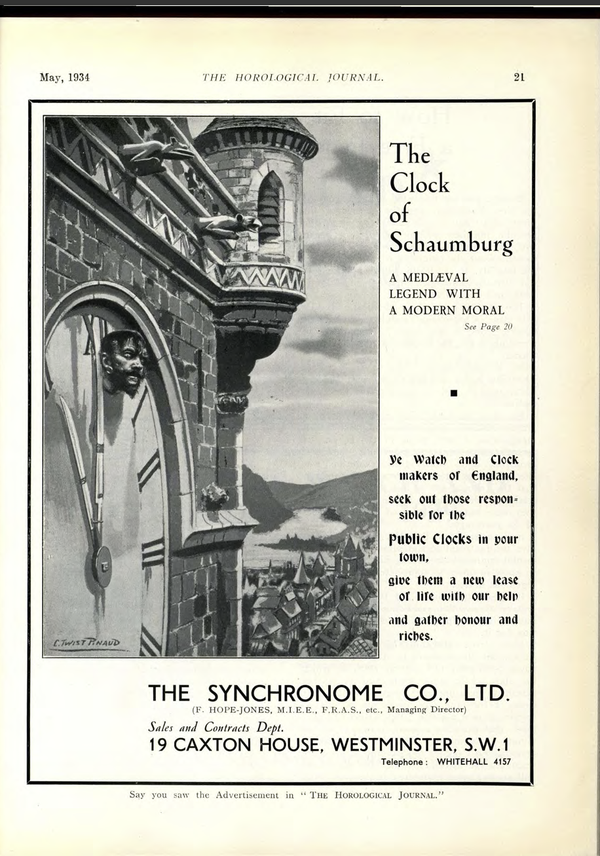

The author Kirby Draycott provided Synchronome with the inspiration (and image) for their 1934 advert featuring death by turret clock at Schaumburg Castle. However, Draycott had a precedent of his own.

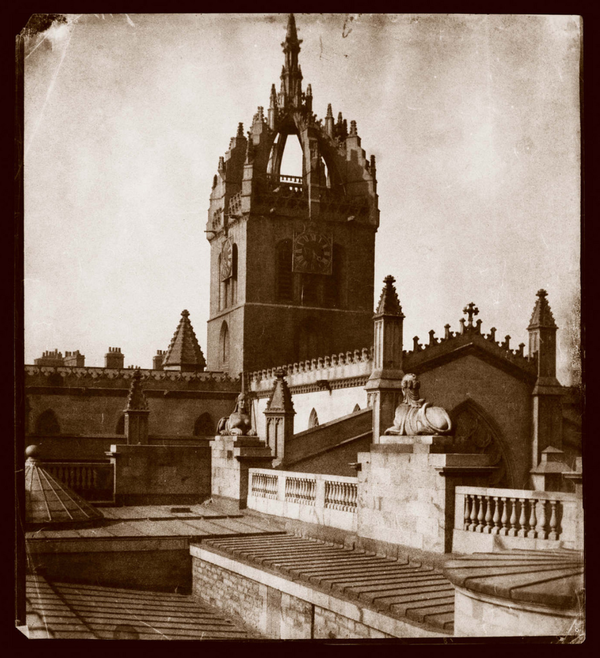

In 1838, Edgar Allen Poe published in Blackwood’s Magazine ‘A Predicament’: an ironic gothic parody about a young lady who sticks her head through an ‘aperture’ in the ‘vast, venerable’ steeple of a Gothic cathedral in Edinburgh – possibly St Giles', in Parliament Square – in search of a glorious view, only to discover she is stuck with her head through the dial.

The hands – ‘not … less than ten feet in length’ – are of steel, and fast advancing (a minute hand had been installed at St Giles' in 1797). However, Poe’s heroine is cheerfully unconcerned with her (titular) predicament and focuses on enjoying ‘the glorious prospect below’ until the hands’ advancement makes her eyes pop out, followed by her head, upon which she returns headless to the street.

Whereas the clock of Schaumberg was elaborately modified to accommodate Draycott’s imagined execution, Poe describes the dangerous aperture as a pre-existing ‘opening in the dial-plate’ through which the clock attendant can adjust the hands – though the heroine speculates that it ‘must have appeared, from the street, as a large key-hole, such as we see in the face of the French watches’. This presumably alludes to a winding arbor, in which context the comparison between a turret clock and a watch establishes a comical contrast of scale.

At the same time, Poe seems less interested in horological practicalities than the prurient associations of the giant ‘keyhole’, which suggests a quest for hidden (and forbidden) knowledge.

Ultimately, the heroine’s eagerness to penetrate mysterious holes is punished by what she herself dubs ‘the ponderous and terrific Scythe of Time’. For Poe (later to return to horological torture in ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’), decapitation by turret clock therefore provides an ironic illustration of time’s inexorable assault on youth – though perhaps here it matters less exactly what time it is.

Dead on 12 o'clock

This post was written by Kirsten Tambling

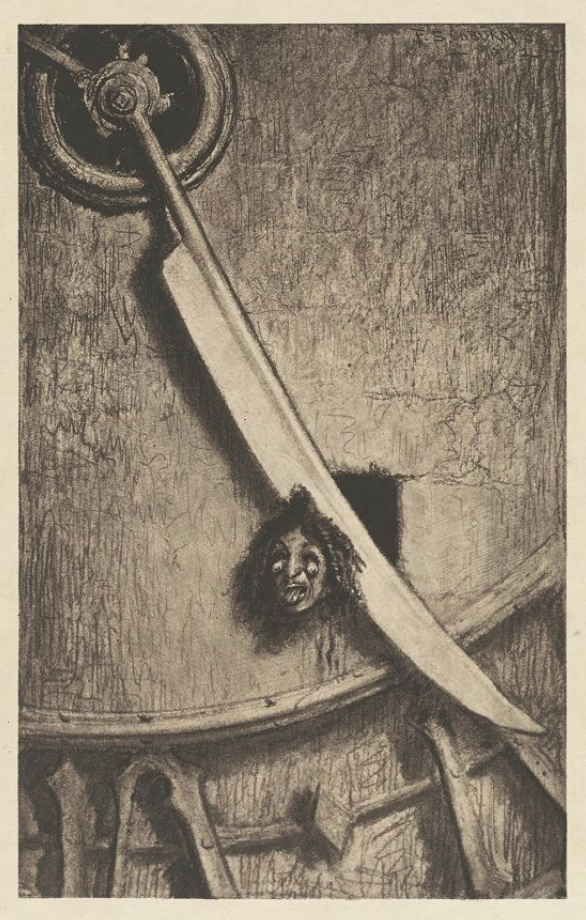

Frank Hope-Jones must have had a taste for the gothic. In 1934, his Synchronome Company advertised the new ‘Synchronomains’ turret clock unit citing a ‘medieval legend with a modern moral’.

The ‘legend’ went that during the Peasants’ War of 1524–5, the rebel Goerz of the Iron Hand was taken hostage at Schaumburg Castle, where his enemies had made implausibly macabre preparations for his torture and execution. Dragged to the summit of the clock tower, Goerz’s head was thrust through the enormous dial just below the 12.

The great hands had been reversed – the minute now the shorter of the two – and replaced with blades. At every pass, the reduced minute hand would pierce the victim’s flesh, until the newly extended hour reached the twelve, when his head would be severed from his body and fall into the moat.

However, the Synchronome Company was sceptical any weight-driven turret clock could muster the requisite force for the coup de grace. If only it had been a Synchronomains! In that case, 'either hand would have completed the headsman’s task with ease – without interfering with the accuracy of the clock!'

The story was pitched as a medieval legend, but someone at Synchronome must have been reading The Royal Magazine, a cheap monthly run by C. Arthur Pearson. 'The Clock Face of Schaumburg', by Kirby Draycott, appeared in its inaugural issue (November 1898). The frontispiece showing Goerz’s final moments – later snaffled by Synchronome – was by the English artist C. Twist Pinaud, who seems to have taken some liberties with the clockless Schaumburg Castle.

However, Draycott’s protagonist was real enough: the historical Götz von Berlichingen (1480–1562) was a mercenary soldier whose titular prosthetic limb can still be seen at Jagsthausen Castle.

His end was less bloody but arguably equally unlikely – he died peacefully in his 80s. Perhaps Draycott thought death by turret clock an ironically fitting alternative end for 'the iron hand'.

At any rate, the purportedly medieval story certainly furnished an attention-grabbing campaign for the Synchronomains, which promised clocks unfailingly dead on the hour.

The conservation of precision horology

This post was written by Jonathan Betts

A few weeks ago I attended a fascinating international three-day conference on the conservation of historic regulators and chronometers, hosted by the curatorial and conservation staff at Palermo Observatory in Sicily, part of the INAF group (Instituto Nationale di Astrofisica) of Italian observatories, all of which have historic collections of instruments and timekeepers.

The lectures, which were presented by specialist curators and conservators from Italy, UK, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, covered a great range of horological subjects from philosophical preservation, practical conservation of collections and a more general discussion of the care and preservation of these especially vulnerable objects.

Although the various papers reflected quite different perspectives, all the speakers found common ground on the principles of care and spoke with one voice on the aims of their roles as custodians of our historic collections.

A particular aim of the conference, discussed in depth in the final group meeting, was to formulate a common set of guidelines for future curators and conservators, and an internet forum was then established to continue the dialogue in future.

The hosts at Palermo Observatory, Ileana Chinnici and Maria Carotenuto, to whom we were especially grateful for organising the event, were particularly keen to seek advice from delegates on formulating a programme of care for the fine collections at Palermo. This might then apply to all the historic precision instruments in the Italian observatories under INAF.

We learned some fascinating statistics:

-- these instruments represent 80 per cent of the astronomical heritage in Italy, and 10 per cent of these objects are timekeepers of one kind or another;

-- in all the various observatory collections there are 53 clocks, 31 chronographs and 12 box chronometers;

-- 25 per cent of the horological material is of British manufacture, 20 per cent is Swiss, 13 per cent is Austrian/German, 7 per cent is French, and 35 per cent is Italian.

Naturally the regulators at Palermo formed the focus of much interest and discussion during the conference, and what fine things they are! The stellar list of makers includes Mudge & Dutton, Janvier, Vulliamy, Cumming & Grant, Frodsham, Dent and Riefler.

Palermo Observatory had been founded in 1790 with Guiseppe Piazzi as its first astronomer. It was Piazzi who, on a visit to London and Paris in the late 1780s, commissioned the regulators from Mudge & Dutton, Cumming & Grant and Janvier as the first timekeepers for astronomical use at Palermo.

Having recently studied and written about the works of Alexander Cumming (Antiquarian Horology, March 2022), I found the example by Cumming & Grant, which has Cumming's own form of gravity escapement, of particular interest. It is very similar to the regulator signed by Grant only, in the Clockmakers' Company Museum in the Science Museum, London, both clocks being of superb quality.

A really interesting and valuable three days; there will hopefully be a chance to return soon to study this fine collection more closely.

The various rooms in the historic building now form the museum of the observatory, which can be visited in person or virtually.

A horological playlist

This post was written by Tabea Rude

I thought it would be fun to have a horological playlist.

Maybe it will come in handy for a 'clock-y' party someday, or just for everyday use if we feel we don't have enough horology in our lives.

Hopefully this playlist can be expanded to cover the full length of a party, or two!

The Spotify app can be downloaded from the Apple app store or Google Play (Android).

Feel free to add your own horologically themed songs.

The most perfect of Swiss watchmakers

This post was written by Helen Chapman

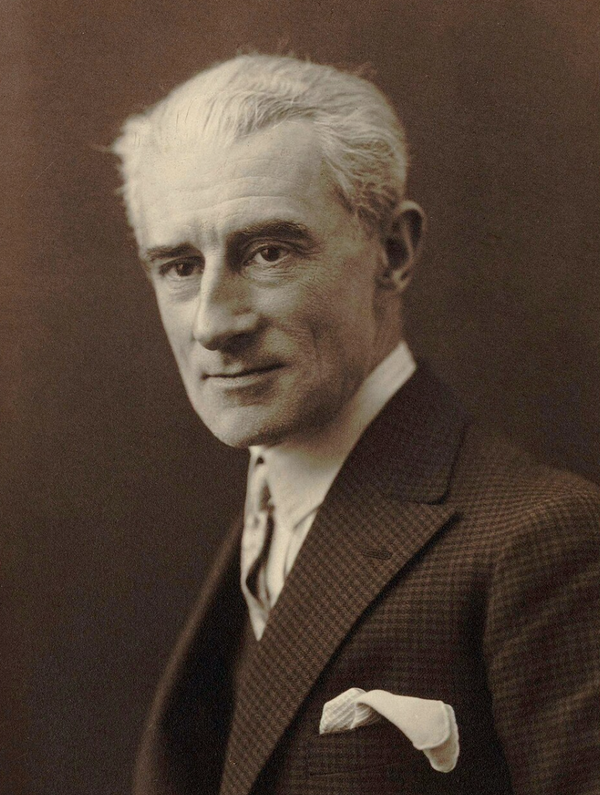

St Mary-at-Hill church, across Lovat Lane from the Society’s office, recently hosted a wonderful recital by the pianist Yuki Negishi, who performed a programme of work by Joseph Maurice Ravel in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

Aside from the music, what caught my attention was Yuki’s comment that, unlike the stereotype of artists inspired by the natural world, Ravel was a man fascinated by the machinery of modernity, by factories and, indeed, clocks.

'The most perfect of Swiss watchmakers' is an often-cited description of Ravel made by Igor Stravinsky, most likely referring to the exquisite precision which characterises much of Ravel’s music.

The comment could be seen as particularly appropriate, however, as Ravel’s great-great-grandfather Denis Gabriel Rousset (1735–1803), from Versoix, Switzerland, is indeed recorded as ‘Maître-horloger’.

Moreover, both Ravel’s father, Pierre, and brother, Edouard, were engineers and he clearly shared their love of the mechanical, saying in 1927: ‘in my childhood I was much interested in mechanisms … I visited factories often, very often, as a small boy with my father. It was these machines, their clicking and roaring, which, with the Spanish folk songs … formed my first instruction in music!’

This interest in mechanical sounds has been noted by many critics of Ravel’s music, and indeed he wrote an entire opera based in a clock shop, as featured in this blog by Peter de Clercq – which begins with metronomes representing three clocks ticking at different speeds, their beats coinciding at a precise interval.

From the program at St Mary-at-Hill, the haunting ‘Le gibet’ from Gaspard de la Nuit is notable for the persistent tolling of a distant bell throughout and, most famously, there is Bolero, the orchestral arrangement for which is dominated by the unwavering and ‘robotic’ snare drum.

Having attended the recital as a break from my desk, it was an unexpected bonus to learn about such an interesting link between the musical and horological worlds.

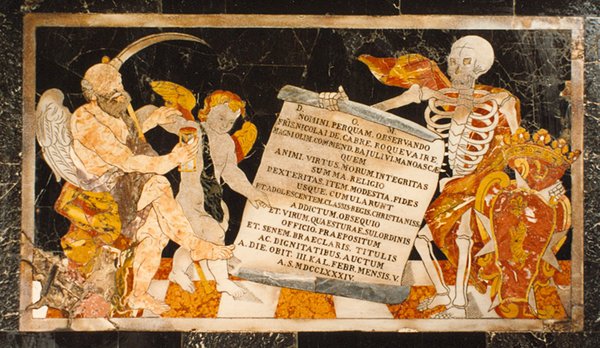

Time symbols in St John’s Co-Cathedral, Malta

This post was written by Peter de Clercq

As he knows that I am interested in horology on gravestones (see my earlier blog ‘Time symbols in cemeteries’ posted in October last year), Anthony Turner kindly sent me a few photos taken during a recent visit to Malta.

In St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valetta, the floors are entirely paved with inlaid marble tombstones of the knights of St John. They were all made following original designs and composed of coloured inlaid marble. They date from the early seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century.

The in total 405 tombstones and monuments, of which 154 are in the main nave, are all illustrated on the wonderful website of the Co-Cathedral. There we learn that they commemorate some of the most illustrious knights of the Order. Several of them were members of powerful aristocratic families of Europe. They were grand priors, admirals and bailiffs, amongst others, and were often referred to as Most Illustrious Lord Brother Illustrissimus Dominus Frater.

The Latin epitaphs describe the virtues of the individual knight. Each tombstone is charged with messages of triumph, fame, victory and death. Symbols, both ecclesiastical and profane, are used in a vibrant visual language of colour and design.

One of the most popular symbols is the image of death represented by a skeleton, often with a sickle and an hourglass, and occasionally a clock or clock dial, all signifying the passage of time. Here are some striking examples.

If you ever have the chance to visit Malta, do not miss St John’s Co-Cathedral. Anthony assures me it is quite spectacular.

All photos reproduced here courtesy of St John’s Co-Cathedral.

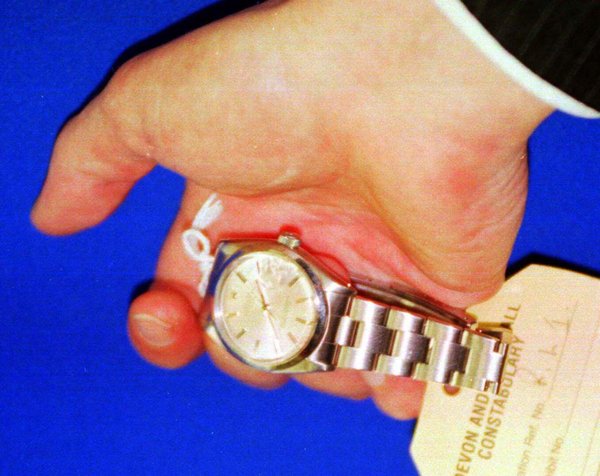

Stop all the clocks – a murderous take on the subject

This post was written by James Nye

Albert Johnson Walker, a Canadian, was born in 1946. In the 1980s, he defrauded his clients of millions of Canadian dollars. He abandoned most of his family and moved to Europe, ending up in Harrogate, Yorkshire. In 1993, he was charged in Canada, in absentia, with 18 counts of fraud, theft and money laundering. In time he became one of Canada's most wanted criminals.

Covering his tracks, Walker changed his name to David Davis, and set up a new business with a television repairman called Ronald Joseph Platt. Back in 1967, Platt, a 22-year-old Englishman in the Army, bought a Rolex Oyster Perpetual in Osnabruck, Germany, serial number 154402.

Fast forward to the 1990s again, and Platt ran out of money. Walker suggested emigration to Canada and a new life. Walker bankrolled Platt’s trip, but claimed he needed Platt's driver's licence and birth certificate to keep the UK business running. Once Platt was off the scene, Walker assumed his identity. So, he’d started as Walker, changed to Davis, and now he was Platt.

The real Platt ran out of money in Canada and returned to England in 1995, inconveniently for Walker (now calling himself Platt). Walker took Platt on a fishing trip on 20 July 1996 where he probably knocked him out with a heavy blow to the head, then weighed him down with an anchor and dumped his body in the sea.

Two weeks later, the body was discovered in the English Channel. The only identifiable object on the body was the Rolex watch – with its crown duly screwed down tight. It showed the time as 11.35 and a calendar date of 22. Enquiries with Rolex revealed the location of the serial number, hidden by the strap. Rolex confirmed the name and address of the owner, and the watch's service record for the 1980s.

With Platt’s identity established, investigations inexorably led to other people associated with him – including Walker, now masquerading again as David Davis. A GPS fix for Walker’s boat tallied with calculations for when the watch's power reserve would be exhausted. Walker was apprehended shortly thereafter. In 1998 he was tried and convicted for murder. Without the watch, the murder would have gone completely unsolved.

Vorwarnschlag – or signalling the arrival of the hour

This post was written by James Nye

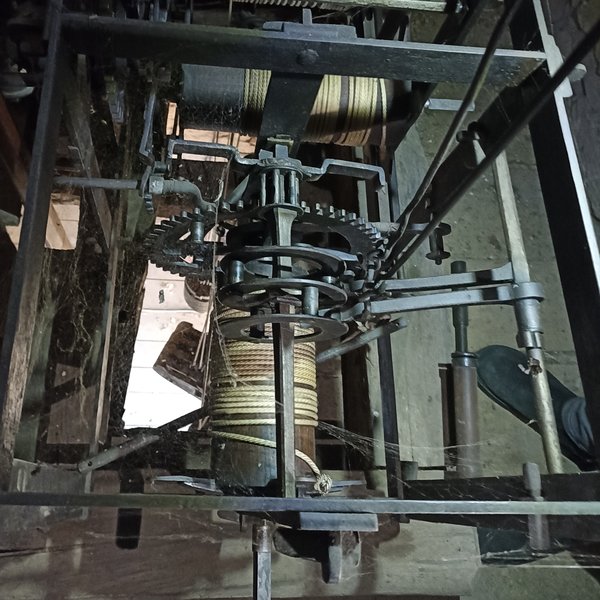

A few of us travelled to Transylvania, Romania, in early March 2025. We were hosted by a local contact and friend, Dragoș Poponea, who guided us around an amazing array of fortified Transylvanian Saxon churches, often equipped with turret clocks from makers in Germany or the former Austro-Hungarian Empire (e.g. at Biertan, see image below).

Dragoș has the care of many of these church clocks, a huge task in a region where the Saxon population largely abandoned their long-term homelands in the wake of the 1989 revolution. Communities that could once purchase a top-of-the-range Mannhardt ‘freischwinger’ clock from Munich (or similar) have disappeared, and the resources to maintain such wonderful devices are now scarce.

Climbing around dusty towers and getting ourselves magnificently filthy, we were delighted to discover something new to all of us. Indeed, even for our friends who are experts in Germanic turret clock horology, this was something perhaps heard of, but not witnessed.

In a handful of churches, Dragoș opened our eyes to hour-striking turret clocks, with a third train that did not strike the quarters but instead provided a warning of the impending hour.

In Germanic dialects, this train provides a ‘vorschlag’, or ‘weckschlag’, or perhaps most accurately ‘vorwarnschlag’, which we might translate as ‘forewarning alarm’. Prior to knowing the Germanic terminology, the British team landed upon ‘hour-signalling’ to describe the feature.

Just before the hour, this ‘hour signalling train’ is let off. By one of several different techniques it is designed to make a bell strike rapidly. An alarm call, effectively. The end of the alarm leads to the hour-striking train being let off, which will then sound on a much larger and deeper bell. The function is simple. ‘Pay attention everyone! We are about to sound the hour. Listen up so you count the correct number!’

There are variants in the way the alarm call is achieved. One type involves using two hammers to strike a fixed bell, while the other swings a smaller bell so that its clapper operates.

With the fixed bell type, one very clever arrangement involves just one pinwheel, which acts on a two-part lifting lever (e.g. at Roșia).

The first part of the lever to be lifted will begin to lift one hammer, but will also, with a small mechanical delay, lift the second part of the lever, which is connected to the other hammer.

Since the two hammers have been lifted to different heights, when they are released they can strike the same bell (even the hour bell), but with successive blows.

With the swinging bell type, the arbor on which the bell is mounted can be swung to and fro by wires attached at the ends of a cross-piece fixed to the arbor.

The two hammers can be actuated by a double pinwheel with two sets of lifting pins acting on two lifting levers, one for each hammer (e.g. at Cincșor).

However, in a more elegant arrangement, the circular motion of a wheel is converted, via a crank and forked lever, to a reciprocating action, thus pulling the two wires successively to swing the small bell (e.g. at Șelimbăr). For a video, click here.

There may well be more variants. All of this was very new to us, and hugely interesting. There is clearly a strong tradition in the rural and agricultural Transylvanian Saxon region to signal to the population that the hour is coming.

The system is reminiscent of the idea employed in clocks from the Comptoise region of eastern France where the hour is struck twice, two minutes apart, to give the listener a chance to ‘hear again’ the hour, but the Transylvanian ‘hour signalling’ surely provides a clearer message.

It’s about time we learned a bit more about such a sensible tradition.

Patenting precision: early motorsport timekeeping

This post was written by Marie Reber Ondrejikova

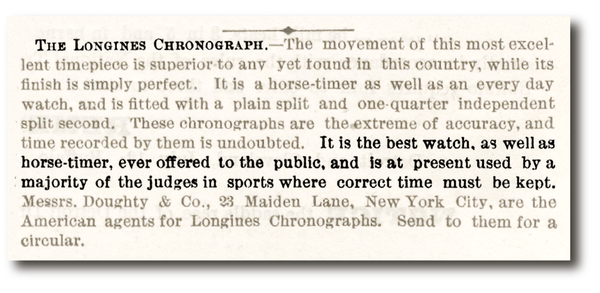

An advertisement dated 29th January 1881 in the New York weekly The Spirit of the Times proclaims that: ‘a gentleman not only secures a timer for the track, but also an excellent watch for ordinary purposes, that will last him a life-time. The timer beats fifths of seconds, which is admitted to be the most accurate movement’.

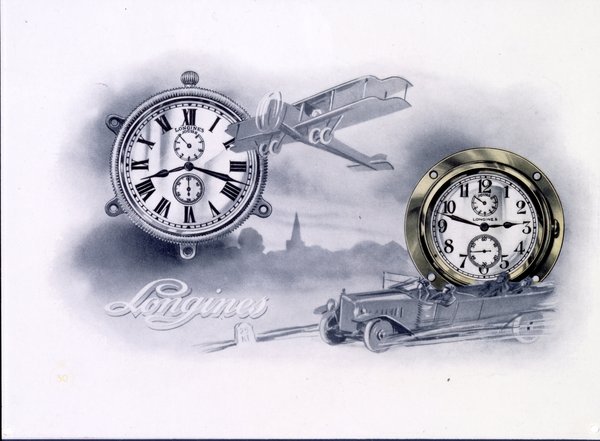

The watchmaking workshop founded by Auguste Agassiz produced its first movements under the Longines name in 1867, and in 1879 brought to market its first chronograph movement, the calibre 20H. Although this calibre did not include a minute totaliser, it established the Longines name on American racecourses.

In these early years the focus was on horse racing but by 1886, Longines was already equipping the majority of sports judges.

In 1889, Longines developed its second chronograph, the calibre 19CH, followed by increasingly sophisticated chronographs such as the calibre 19.73 in 1897, capable of measuring times to one-tenth of a second and intermediate times.

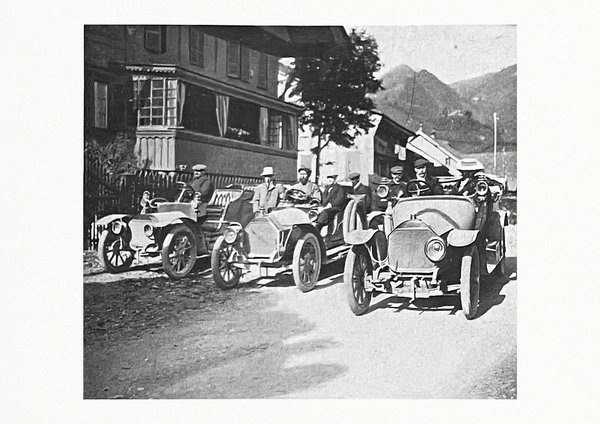

These technical advancements were well timed, with the first automobile race in the United States taking place in 1895.

The early motorsport races were spectacular events. The public were thrilled by the courage of the drivers and admired the beautiful machinery, still rarely seen on the roads. These competitions played an important role in the development of the automobile and in improving the performance and reliability of vehicles.

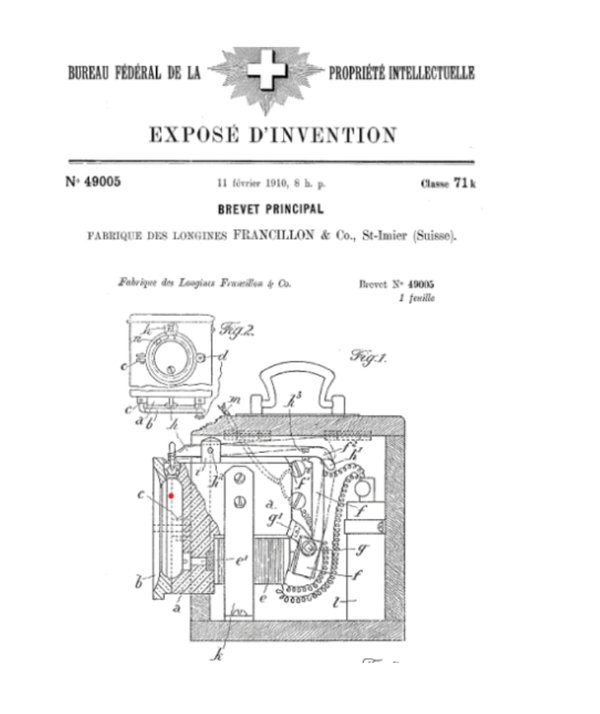

As motor cars gained popularity and speeds increased, new sporting events emerged alongside professional timekeeping. In 1910, Longines filed patent CH49005 for an electric control device for a pocket chronograph. This patent was of particular importance in the field of motor sports timekeeping, as it explicitly specified that the invention was intended for the velocipede and automobile disciplines.

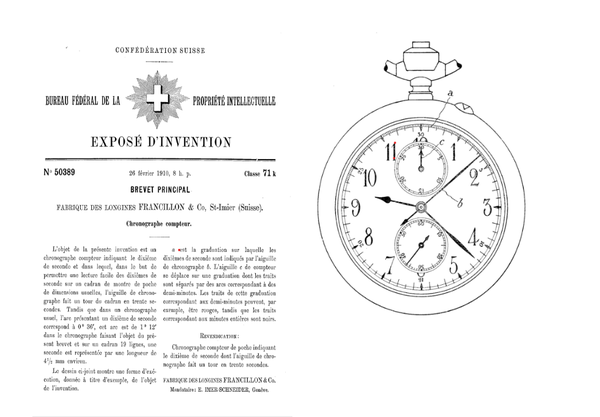

In addition to this patent, in 1910 Longines also filed a patent for a chronograph counter displaying time to the tenth of a second (patent no. 50389), an innovation that required a high-frequency movement with 36,000 vibrations per hour.

These early patents laid the foundations for the very first sports timekeeping service, adding cutting-edge electrical skills to watchmaking know-how, and the creation of timekeeping control systems.